University of Cincinnati

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Year's Music

This is a reproduction of a library book that was digitized by Google as part of an ongoing effort to preserve the information in books and make it universally accessible. https://books.google.com fti E Y LAKS MV5IC 1896 juu> S-q. SV- THE YEAR'S MUSIC. PIANOS FOR HIRE Cramer FOR HARVARD COLLEGE LIBRARY Pianos BY All THE BEQUEST OF EVERT JANSEN WENDELL (CLASS OF 1882) OF NEW YORK Makers. 1918 THIS^BQQKJS FOR USE 1 WITHIN THE LIBRARY ONLY 207 & 209, REGENT STREET, REST, E.C. A D VERTISEMENTS. A NOVEL PROGRAMME for a BALLAD CONCERT, OR A Complete Oratorio, Opera Recital, Opera and Operetta in Costume, and Ballad Concert Party. MADAME FANNY MOODY AND MR. CHARLES MANNERS, Prima Donna Soprano and Principal Bass of Royal Italian Opera, Covent Garden, London ; also of 5UI the principal ©ratorio, dJrtlustra, artii Sgmphoiu) Cxmctria of ©wat Jfvitain, Jtmmca anb Canaba, With their Full Party, comprising altogether Five Vocalists and Three Instrumentalists, Are now Booking Engagements for the Coming Season. Suggested Programme for Ballad and Opera (in Costume) Concert. Part I. could consist of Ballads, Scenas, Duets, Violin Solos, &c. Lasting for about an hour and a quarter. Part II. Opera or Operetta in Costume. To play an hour or an hour and a half. Suggested Programme for a Choral Society. Part I. A Small Oratorio work with Chorus. Part II. An Operetta in Costume; or the whole party can be engaged for a whole work (Oratorio or Opera), or Opera in Costume, or Recital. REPERTOIRE. Faust (Gounod), Philemon and Baucis {Gounod) (by arrangement with Sir Augustus Harris), Maritana (Wallace), Bohemian Girl (Balfe), and most of the usual Oratorios, &c. -

©Studentsavvy Music Around the World Unit I Thank You For

©studentsavvy Music Around the World Unit I thank you for StudentSavvy © 2016 downloading! Thank you for downloading StudentSavvy’s Music Around the World Unit! If you have any questions regarding this product, please email me at [email protected] Be sure to stay updated and follow for the latest freebies and giveaways! studentsavvyontpt.blogspot.com www.facebook.com/studentsavvy www.pinterest.com/studentsavvy wwww.teacherspayteachers.com/store/studentsavvy clipart by EduClips and IROM BOOK http://www.hm.h555.net/~irom/musical_instruments/ Don’t have a QR Code Reader? That’s okay! Here are the URL links to all the video clips in the unit! Music of Spain: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=_7C8MdtnIHg Music of Japan: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=5OA8HFUNfIk Music of Africa: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=4g19eRur0v0 Music of Italy: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=U3FOjDnNPHw Music of India: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=qQ2Yr14Y2e0 Music of Russia: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=EEiujug_Zcs Music of France: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Ge46oJju-JE Music of Brazil: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=jQLvGghaDbE ©StudentSavvy2016 Don’t leave out these countries in your music study! Click here to study the music of Mexico, China, the Netherlands, Germany, Australia, USA, Hawaii, and the U.K. You may also enjoy these related resources: Music Around the WorLd Table Of Contents Overview of Musical Instrument Categories…………………6 Music of Japan – Read and Learn……………………………………7 Music of Japan – What I learned – Recall.……………………..8 Explore -

Heitor Villa-Lobos and the Parisian Art Scene: How to Become a Brazilian Musician*

1 Mana vol.1 no.se Rio de Janeiro Oct. 2006 Heitor Villa-Lobos and the Parisian art scene: how to become a Brazilian musician* Paulo Renato Guérios Master’s in Social Anthropology at PPGAS/Museu Nacional/UFRJ, currently a doctoral student at the same institution ABSTRACT This article discusses how the flux of cultural productions between centre and periphery works, taking as an example the field of music production in France and Brazil in the 1920s. The life trajectories of Jean Cocteau, French poet and painter, and Heitor Villa-Lobos, a Brazilian composer, are taken as the main reference points for the discussion. The article concludes that social actors from the periphery tend themselves to accept the opinions and judgements of the social actors from the centre, taking for granted their definitions concerning the criteria that validate their productions. Key words: Heitor Villa-Lobos, Brazilian Music, National Culture, Cultural Flows In July 1923, the Brazilian composer Heitor Villa-Lobos arrived in Paris as a complete unknown. Some five years had passed since his first large-scale concert in Brazil; Villa-Lobos journeyed to Europe with the intention of publicizing his musical output. His entry into the Parisian art world took place through the group of Brazilian modernist painters and writers he had encountered in 1922, immediately before the Modern Art Week in São Paulo. Following his arrival, the composer was invited to a lunch in the studio of the painter Tarsila do Amaral where he met up with, among others, the poet Sérgio Milliet, the pianist João de Souza Lima, the writer Oswald de Andrade and, among the Parisians, the poet Blaise Cendrars, the musician Erik Satie and the poet and painter Jean Cocteau. -

ETHEL MARY SMYTH DBE, Mus.Doc, D.Litt. a MUSICAL

ETHEL MARY SMYTH DBE, Mus.Doc, D.Litt. A MUSICAL TIMELINE compiled by Lewis Orchard Early days & adolescence in Frimley 1858 Born 22 April at 5 Lower Seymour Street (now part of Wigmore Street), Marylebone, London; daughter of Lieutenant Colonel (then) John Hall Smyth of the Bengal Artillery and Emma (Nina) Smyth. Ethel liked to claim that she was born on St. George's Day 23 April but her birth certificate clearly states 22 April. Baptised at St. Marylebone parish church on 28 May, 1858. On return of father from India the family took up residence at Sidcup Place, Sidcup, Kent where she spent her early years up to age 9. Mostly educated by a series of governesses 1867 When father promoted to an artillery command at Aldershot the family moved to a large house 'Frimhurst' at Frimley Green, Surrey, which later he purchased. Sang duets with Mary at various functions and displayed early interest in music. 1870 'When I was 12 a new victim (governess) arrived who had studied music at the Leipzig Conservatorium'. This was Marie Louise Schultz of Stettin, Pomerania, Germany (now Szezecin, Poland) who encouraged her interest in music and introduced her to the works of the major (German) composers, notably Beethoven.. Later Ethel met Alexander Ewing (also in the army at Aldershot in the Army Service Corps). Ethel became acquainted with him through Mrs Ewing who was a friend of her mother. Ewing was musically well educated and was impressed by Ethel's piano playing and compositions. He encouraged her in her musical ambitions. He taught her harmony and introduced her to the works of Brahms, List, Wagner and Berlioz and gave her a copy of Berlioz's 'Treatise on Orchestration'. -

The Critical Reception of Beethoven's Compositions by His German Contemporaries, Op. 123 to Op

The Critical Reception of Beethoven’s Compositions by His German Contemporaries, Op. 123 to Op. 124 Translated and edited by Robin Wallace © 2020 by Robin Wallace All rights reserved. ISBN 978-1-7348948-4-4 Center for Beethoven Research Boston University Contents Foreword 6 Op. 123. Missa Solemnis in D Major 123.1 I. P. S. 8 “Various.” Berliner allgemeine musikalische Zeitung 1 (21 January 1824): 34. 123.2 Friedrich August Kanne. 9 “Beethoven’s Most Recent Compositions.” Allgemeine musikalische Zeitung mit besonderer Rücksicht auf den österreichischen Kaiserstaat 8 (12 May 1824): 120. 123.3 *—*. 11 “Musical Performance.” Wiener Zeitschrift für Kunst, Literatur, Theater und Mode 9 (15 May 1824): 506–7. 123.4 Ignaz Xaver Seyfried. 14 “State of Music and Musical Life in Vienna.” Caecilia 1 (June 1824): 200. 123.5 “News. Vienna. Musical Diary of the Month of May.” 15 Allgemeine musikalische Zeitung 26 (1 July 1824): col. 437–42. 3 contents 123.6 “Glances at the Most Recent Appearances in Musical Literature.” 19 Caecilia 1 (October 1824): 372. 123.7 Gottfried Weber. 20 “Invitation to Subscribe.” Caecilia 2 (Intelligence Report no. 7) (April 1825): 43. 123.8 “News. Vienna. Musical Diary of the Month of March.” 22 Allgemeine musikalische Zeitung 29 (25 April 1827): col. 284. 123.9 “ .” 23 Allgemeiner musikalischer Anzeiger 1 (May 1827): 372–74. 123.10 “Various. The Eleventh Lower Rhine Music Festival at Elberfeld.” 25 Allgemeine Zeitung, no. 156 (7 June 1827). 123.11 Rheinischer Merkur no. 46 27 (9 June 1827). 123.12 Georg Christian Grossheim and Joseph Fröhlich. 28 “Two Reviews.” Caecilia 9 (1828): 22–45. -

Sir Joseph Barnby. Born, August 12, 1838; Died, January 28, 1896

THE MUSICAL TIMES.- February I, 1896. SIR JOSEPH BARNBY BORN AUGUST 12, 1838; DIED JANUARY 28, 1896. Close upon each other's steps, during what attractinghas crowds by his renderings of Bach's passed of this ominous year, death and disaster have " Passion" according both to St. Matthewand St. John. followed, and now it is our melancholy duty to record So much activity and success prepared the way for the passing away of Sir Joseph Barnby. Mournful still higher things, and, in 1875, Mr. Barnby was under any circumstances, there are some conditions appointed Precentor and Director of Musical Instruc- amid which the dissolution of the body loses much tion at Eton College. That important position he of its terror. When a man has finished his life's work, retained till shortly before election to a still more and the enfeebled frame stoops under a weight onerous of and responsible post as Principal of the years, we can calmly think, with Lord Bacon, that Guildhall School of Music. With resignation from "it is as natural to die as to be born." But the Eton, his direct, personal service to the Church ceased. case is wholly different when, in the full But vigour he worked of for the music of worship in more maturity and in the midst of work, one than is suddenlyone way, being as active with his pen as at the struck down, as by a bolt from the blue. organ or in choir practice. He leaves behind him a long Thus did Joseph Barnby die. As far as our list of Services, Anthems, hymn-tunes, and Chants, many knowledge goes, his health had lately given of which have come into general use, are highly prized, no cause for uneasiness. -

Amherst Early Music Festival Directed by Frances Blaker

Amherst Early Music Festival Directed by Frances Blaker July 8-15, and July 15-22 Connecticut College, New London CT Music of France and the Low Countries Largest recorder program in U.S. Expanded vocal programs Renaissance reeds and brass New London Assembly Festival Concert Series Historical Dance Viol Excelsior www.amherstearlymusic.org Amherst Early Music Festival 2018 Week 1: July 8-15 Week 2: July 15-22 Voice, recorder, viol, violin, cello, lute, Voice, recorder, viol, Renaissance reeds Renaissance reeds, flute, oboe, bassoon, and brass, flute, harpsichord, frame drum, harpsichord, historical dance early notation, New London Assembly Special Auditioned Programs Special Auditioned Programs (see website) (see website) Baroque Academy & Opera Roman de Fauvel Medieval Project Advanced Recorder Intensive Ensemble Singing Intensive Choral Workshop Virtuoso Recorder Seminar AMHERST EARLY MUSIC FESTIVAL FACULTY CENTRAL PROGRAM The Central Program is our largest and most flexible program, with over 100 students each week. RECORDER VIOL AND VIELLE BAROQUE BASSOON* Tom Beets** Nathan Bontrager Wouter Verschuren It offers a wide variety of classes for most early instruments, voice, and historical dance. Play in a Letitia Berlin Sarah Cunningham* PERCUSSION** consort, sing music by a favorite composer, read from early notation, dance a minuet, or begin a Frances Blaker Shira Kammen** Glen Velez** new instrument. Questions? Call us at (781)488-3337. Check www.amherstearlymusic.org for Deborah Booth* Heather Miller Lardin* Karen Cook** Loren Ludwig VOICE AND THEATER a full list of classes by May 15. Saskia Coolen* Paolo Pandolfo* Benjamin Bagby** Maria Diez-Canedo* John Mark Rozendaal** Michael Barrett** New to the Festival? Fear not! Our open and inviting atmosphere will make you feel at home Eric Haas* Mary Springfels** Stephen Biegner* right away. -

Roméo Et Juliette

Charles Gounod Roméo et Juliette CONDUCTOR Opera in five acts Plácido Domingo Libretto by Jules Barbier and Michel Carré PRODUCTION Guy Joosten Saturday, December 15, 2007, 1:00–4:20pm SET DESIGNER Johannes Leiacker COSTUME DESIGNER Jorge Jara LIGHTING DESIGNER David Cunningham The production of Roméo et Juliette is made possible by generous gifts from the CHOREOGRAPHER Gramma Fisher Foundation, Marshalltown, Iowa, Sean Curran and The Annenberg Foundation. Additional funding for this production was provided by Mr. and Mrs. Sid R. Bass, Hermione Foundation, Karen and Kevin Kennedy, Mr. and Mrs. William R. Miller, Bill Rollnick and Nancy Ellison Rollnick, and Mr. and Mrs. Ezra K. Zilkha. GENERAL MANAGER Peter Gelb MUSIC DIRECTOR James Levine 2007-08 Season The 319th Metropolitan Opera performance of Charles Gounod’s This performance is broadcast live over The Toll Brothers– Roméo et Metropolitan Opera International Radio Network, Juliette sponsored by Toll Brothers, America’s luxury home builder®, Conductor with generous long- Plácido Domingo term support from The Annenberg IN ORDER OF VOCAL APPEARANCE Foundation and the Tybalt Friar Laurence Vincent A. Stabile Marc Heller Robert Lloyd Endowment Fund for Paris Stéphano Broadcast Media, Louis Otey Isabel Leonard and through contributions from Capulet Benvolio listeners worldwide. Charles Taylor Tony Stevenson Juliette The Duke of Verona This afternoon’s Anna Netrebko Dean Peterson performance is also being transmitted Mercutio live in high definition Nathan Gunn to movie theaters in the -

Beethoven (1819-1823) (1770-1827)

Friday, May 10, 2019, at 8:00 PM Saturday, May 11, 2019, at 3:00 PM MISSA SOLEMNIS IN D, OP. 123 Ludwig van Beethoven (1819-1823) (1770-1827) Tami Petty, soprano Helen KarLoski, mezzo-soprano Dann CoakwelL, tenor Joseph Beutel, bass-baritone Kyrie GLoria Credo Sanctus and Benedictus* Agnus Dei * Jorge ÀviLa, violin solo Approximately 80 minutes, performed without intermission. PROGRAM NOTES The biographer Maynard SoLomon him to conceptuaLize the Missa as a work described the Life of Ludwig van of greater permanence and universaLity, a Beethoven (1770-1827) as “a series of keystone of his own musicaL and creative events unique in the history of personaL Legacy. mankind.” Foremost among these creative events is the Missa Solemnis The Kyrie and GLoria settings were (Op. 123), a work so intense, heartfeLt and largely complete by March of 1820, with originaL that it nearly defies the Credo, Sanctus, Benedictus and categorization. Agnus Dei foLLowing in Late 1820 and 1821. Beethoven continued to poLish the work Beethoven began the Missa in 1819 in through 1823, in the meantime response to a commission from embarking on a convoLuted campaign to Archduke RudoLf of Austria, youngest pubLish the work through a number of son of the Hapsburg emperor and a pupiL competing European houses. (At one and patron of the composer. The young point, he represented the existence of no aristocrat desired a new Mass setting for less than three Masses to various his enthronement as Archbishop of pubLishers when aLL were one and the Olmütz (modern day Olomouc, in the same.) A torrent of masterworks joined Czech RepubLic), scheduLed for Late the the Missa during this finaL decade of following year. -

Moses and Frances Asch Collection, 1926-1986

Moses and Frances Asch Collection, 1926-1986 Cecilia Peterson, Greg Adams, Jeff Place, Stephanie Smith, Meghan Mullins, Clara Hines, Bianca Couture 2014 Ralph Rinzler Folklife Archives and Collections Smithsonian Center for Folklife and Cultural Heritage 600 Maryland Ave SW Washington, D.C. [email protected] https://www.folklife.si.edu/archive/ Table of Contents Collection Overview ........................................................................................................ 1 Administrative Information .............................................................................................. 1 Arrangement note............................................................................................................ 3 Biographical/Historical note.............................................................................................. 2 Scope and Contents........................................................................................................ 2 Names and Subjects ...................................................................................................... 3 Container Listing ............................................................................................................. 5 Series 1: Correspondence, 1942-1987 (bulk 1947-1987)........................................ 5 Series 2: Folkways Production, 1946-1987 (bulk 1950-1983).............................. 152 Series 3: Business Records, 1940-1987.............................................................. 477 Series 4: Woody Guthrie -

Charles Gounod Faust Vittorio Grigolo ∙ René Pape Angela Gheorghiu ∙ Dmitri Hvorostovsky Orchestra of the Royal Opera House Conducted by Evelino Pidò

CHARLES GOUNOD FAUST VITTORIO GRIGOLO ∙ RENÉ PAPE ANGELA GHEORGHIU ∙ DMITRI HvOROSTOVSKY ORCHESTRA OF THE ROYAL OpERA HOUSE CONDUCTED BY EvELINO PIDÒ STAGED BY DAVID MCVICAR CHARLES GOUNOD FAUST Charles-François Gounod’s Faust was once one of the most Conductor Evelino Pidò famous and most performed of all operas: at Covent Garden Orchestra Orchestra of the it was heard every season between 1863 and 1911. Jules Barbier Royal Opera House and Michel Carré’s libretto is a tale of romance, temptation, Chorus Royal Opera Chorus and the age-old battle between satanic powers and religion. It is Stage Director David McVicar based on Carré’s play Faust et Marguerite, which in turn is based on Part I of Johann Wolfgang von Goethe’s dramatic poem Faust Vittorio Grigolo Faust, one of the great works of European literature: Weary of Méphistophélès René Pape life and the pursuit of knowledge, the aged Faust contemplates Marguerite Angela Gheorghiu suicide. Méphistophélès promises to satisfy all of his hedonistic Wagner Daniel Grice demands in exchange for his soul. Valentin Dmitri Hvorostovsky Siébel Michèle Losier David McVicar’s lavish production sets the action in the Paris of Marthe Schwertlein Carole Wilson Gounod’s later years, on the eve of the Franco-Prussian War. Charles Edwards’s designs include a memorable Cabaret d’Enfer Video Director Sue Judd and an impressive reconstruction of the Church of Saint-Séverin. They vividly convey the clash between religion and hedonistic entertainment, and provide a powerful backdrop to Gounod’s Length: 182' score. Faust contains much-loved musical highlights including Shot in HDTV 1080/50i the memorable Soldiers’ Chorus, Méphistophélès’s rowdy ‘Song Cat. -

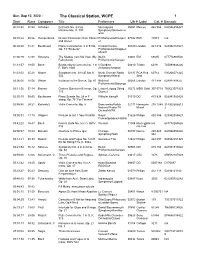

The Classical Station, WCPE 1 Start Runs Composer Title Performerslib # Label Cat

Sun, Sep 13, 2020 - The Classical Station, WCPE 1 Start Runs Composer Title PerformersLIb # Label Cat. # Barcode 00:01:30 07:52 Schubert Entr'acte No. 3 from Minneapolis 05051 Mercury 462 954 028946295427 Rosamunde, D. 797 Symphony/Skrowacze wski 00:10:2208:46 Humperdinck Dream Pantomime from Hansel Philharmonia/Klemper 07382 EMI 13073 n/a and Gretel er 00:20:0838:41 Beethoven Piano Concerto No. 5 in E flat, Curzon/Vienna 04349 London 421 616 028942161627 Op. 73 "Emperor" Philharmonic/Knappert sbusch 01:00:19 12:38 Smetana The Moldau from Ma Vlast (My Berlin 03600 EMI 69005 077776900520 Fatherland) Philharmonic/Karajan 01:13:5718:05 Bach Brandenburg Concerto No. 1 in Il Giardino 04810 Teldec 6019 745099844226 F, BWV 1046 Armonico/Antonini 01:33:02 25:28 Mozart Symphony No. 39 in E flat, K. North German Radio 02135 RCA Red 60714 090266071425 543 Symphony/Wand Seal 02:00:0010:56 Weber Invitation to the Dance, Op. 65 National 00266 London 411 898 02894189820 Philharmonic/Bonynge 02:11:56 37:14 Brahms Clarinet Quintet in B minor, Op. Leister/Leipzig String 10273 MDG Gold 307 0719 760623071923 115 Quartet 02:50:1008:00 Beethoven Piano Sonata No. 24 in F Wilhelm Kempff 01310 DG 415 834 028941583420 sharp, Op. 78 "For Therese" 02:59:40 29:21 Karlowicz Violin Concerto, Op. 8 Danczowka/Polish 02170 Harmonia 278 1088 314902505612 National Radio-TV Mundi 2 Orchestra/Wit 03:30:0111:19 Wagner Prelude to Act 1 from Parsifal Royal 01626 Philips 420 886 028942088627 Concertgebouw/Haitink 03:42:2016:47 Bach French Suite No.