1 the Association for Diplomatic Studies and Training Foreign Affairs

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Table of Contents

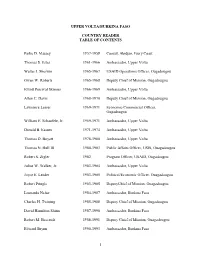

UPPER VOLTA/BURKINA FASO COUNTRY READER TABLE OF CONTENTS Parke D. Massey 1957-1958 Consul, Abidjan, Ivory Coast Thomas S. Estes 1961-1966 Ambassador, Upper Volta Walter J. Sherwin 1965-1967 USAID Operations Officer, Ougadougou Owen W. Roberts 1965-1968 Deputy Chief of Mission, Ougadougou Elliott Percival Skinner 1966-1969 Ambassador, Upper Volta Allen C. Davis 1968-1970 Deputy Chief of Mission, Ougadougou Lawrence Lesser 1969-1971 Economic/Commercial Officer, Ougadougou William E. Schaufele, Jr. 1969-1971 Ambassador, Upper Volta Donald B. Easum 1971-1974 Ambassador, Upper Volta Thomas D. Boyatt 1978-1980 Ambassador, Upper Volta Thomas N. Hull III 1980-1983 Public Affairs Officer, USIS, Ouagadougou Robert S. Zigler 1982 Program Officer, USAID, Ougadougou Julius W. Walker, Jr. 1983-1984 Ambassador, Upper Volta Joyce E. Leader 1983-1985 Political/Economic Officer, Ouagadougou Robert Pringle 1983-1985 DeputyChief of Mission, Ouagadougou Leonardo Neher 1984-1987 Ambassador, Burkina Faso Charles H. Twining 1985-1988 Deputy Chief of Mission, Ougadougou David Hamilton Shinn 1987-1990 Ambassador, Burkina Faso Robert M. Beecrodt 1988-1991 Deputy Chief of Mission, Ouagadougou Edward Brynn 1990-1993 Ambassador, Burkina Faso 1 PARKE D. MASSEY Consul Abidjan, Ivory Coast (1957-1958) Parke D. Massey was born in New York in 1920. He graduated from Haverford College with a B.A. and Harvard University with an M.P.A. He also served in the U.S. Army from 1942 to 1946 overseas. After entering the Foreign Service in 1947, Mr. Massey was posted in Mexico City, Genoa, Abidjan, and Germany. While in USAID, he was posted in Nicaragua, Panama, Bolivia, Chile, Haiti, and Uruguay. -

Crp 2 B 2 0 0

Northwestern University Library Evanston, Illinois 60201 LLIL Cold War and Black Liberation COLD WAR and ~A BLACK LIBERATION The United States and White Rule in Africa, 1948-1968 Thomas J. Noer I University of Missouri Press Columbia, 1985 'I /.~. y Copyright © 1985 by The Curators of the University of Missouri University of Missouri Press, Columbia, Missouri 65211 Printed and bound in the United States of America All rights reserved A FR Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data Noer, Thomas J. Cold War and Black liberation. Bibliography: p. Includes index. 1. Africa-Foreign relations-United States. 2. United States-Foreign relations-Africa. 3. Africa-Foreign relations-1945-1960. 4. Africa-Foreign relations-1960- . 5. United States-Foreign relations-19456. Decolonization- Africa. 7. National liberation movements-Africa. I. Title. DT38.5.A35N64 1985 327.7306 84-19665 ISBN 0-8262-0458-9 ( TM This paper meets the minimum requirements of the American National Standard for Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, Z39.48, 1984. To Linda CONTENTS PREFACE, ix ACKNOWLEDGMENTS, xiii 1. WHITE RULE ON A BLACK CONTINENT Background of a Diplomatic Dilemma, 1 2. RACE AND CONTAINMENT The Truman Administration and the Origins of Apartheid, 15 3. "PREMATURE INDEPENDENCE" Eisenhower, Dulles, and African Liberation, 34 4. NEW FRONTIERS AND OLD PRIORITIES America and the Angolan Revolution, 1961-1962, 61 5. THE PURSUIT OF MODERATION America and the Portuguese Colonies, 1963-1968, 96 6. "NO EASY SOLUTIONS" Kennedy and South Africa, 126 7. DISTRACTED DIPLOMACY Johnson and Apartheid, 1964-1968, 155 8. THE U.S.A. AND UDI America and Rhodesian Independence, 185 9. -

The Foreign Service Journal, March 1968

EVERY 18 SECONDS EVERY 15 SECONDS EVERY 8 SECONDS EVERY 3 SECOND; someone is injured someone is injured someone is injured someone is injured in a motor-vehicle in an "on-the-job" in an accident in an accident accident. accident. in the home. of some kind. The annual toll, The annual toll, The annual toll, The annual toll, according to most according to most according to most according to most recent statistics: recent statistics: recent statistics: recent statistics: 49,000 killed 14,100 killed 28,500 killed 107,000 killed 1,800,000 disabled 2,100,000 disabled 4,300,000 disabled 10,600,000 disabled $8.5 billion lost $6 billion lost $1.3 billion lost $16.9 billion lost Statistics from the National Safety Council and Health Insurance Review. Violence .. vandalism ... burglary .. Accidents of all kinds are reported in increasing numbers in our newspapers. Americans today sense an urgent and growing need for protection from increased perils of daily living. And well they should. In addition to physical harm, or even death, the victim frequently suffers extensive economic loss that can haunt an individual or family for years. Property loss. ACCIDENT: Hospital and doctor bills. Therapy expense. Medicines. And worse—loss of earning power. A Special Report FOR MEMBERS OF THE AMERICAN FOREIGN SERVICE ASSOCIATION To help meet this pressing need, Mutual of Omaha has designed exclusively for members of the AMERICAN FOREIGN SERVICE ASSOCIATION low cost plans. They cover specific accidents or an unlimited variety of ac- cidents-anywhere-at any time. There are plans to provide a monthly income, even for life, for the breadwinner when he is injured and can not work. -

The Foreign Service Journal, July 1945

THANKS FOR YOUR COOPERATION Due in large measure to your co¬ tion, we pledge ourselves to con¬ operation and the example you have tinue serving you to the best of our set, Schenley Reserve is growing ability — and to maintain Schenley more popular every day in overseas Reserve quality at the highest level markets. Occasionally, special ship¬ possible. May you continue to enjoy ments have to be rushed by plane to its distinctive flavor and delicious meet special demands. smoothness in highballs, cocktails, In thanking you for your coopera¬ and other mixed drinks. SCHENLEY INTERNATIONAL CORPORATION Empire State Building, New York, U.S. A. AMERICA’S FINEST WHISKEY... CONTENTS JULY 1945 Cover Picture: Coit Tower, Telegraph Hill, San Francisco (See also page 17) Albany Conference: 1754 7 By Maude Macdonald Hutcheson Yueh 11 By George V. Allen Suggestions for Improving the Foreign Service and Its Administration to Meet Its War and Post-War Responsibilities—Honorable Mention 13 By Ware A dams UNCIO Glimpses—Photos 16 On Telegraph Hill 17 By Harry W. Frantz Selected Questions from the General Foreign Service Examinations of 1945 19 Diplomat Fought Nazis as Partisan Leader 21 By Garnett D. Horner Editors’ Column 22 58 YEARS IN EXPORTING . Montgomery Wards vast Letters to the Editors 23 annual operations have sustained economical mass pro¬ duction of key lines and have effected better products Foreign Service Training School—Photo 24 at competitive prices. A two hundred million dollar cor¬ In Memoriam 24 poration, Wards own some factories outright and have production alliances with others which in many in¬ Births 24 stances include sole export rights for world markets. -

In This Issue

A Quaker Weekly VOLUME 3 APRIL 20, 1957 NUMBER 16 f'!l:mRE is a pow., within IN THIS ISSUE the world able to set men free from fear and anxiety, from hatred and from dread: a power able to bring peace within society and to establish Joseph of Arimathea by William Hubben it among the nations. This power we have known in measure, so toward this we call all men to turn. Ge~rge Washington and Yearly The spirit and the pQJJ.Jer of God enter into our life 'Meeting by Maurice A. Mook thmugh selfless service and through love- through tender pity and patient yet undaunt ed opposition to all wrong. William Wistar Comfort God is Love-love that suf fers, yet is. strong; love that . Memorial Minute triumphs and gives us joy. - EPISTLE oF LoNDON YEARLY MEETING, May 1939 Philadelphia Yearly Meeting, 1957 TWENTY CENTS A COPY Epistle of Philadelphia Yearly Meeting, 1957 $4.50 A YEAR · 254 FRIENDS JOURNAL April 20, 1957 FRIENDS JOURNAL Epistle of Philadelphia Yearly Meeting of the Religious Society of Friends Held Third Month 21st to 27th, 1957 To ALL FRIENDs EvERYWHERE: As we have met in this our 277th annual session, the reading of your epistles has warmed our hearts and given us a sense of shared responsibility. This feeling has been strengthened as visiting Friends have conveyed Published weekly at 1616 Cherry Street, Philadelphia 2, Pennsylvania (Rittenhouse 6-7669) to us their greetings and messages. By Friends Publishing Corporation WILLIAM HUBBEN JEANNE CAVIN A year ago our sessions were permeated by a sense Editor and Manager Advertisements of joy that we were again one in the service of our LOIS L. -

Haverford College Bulletin, New Series, 27-28, 1928-1930

ST* CLASS L-^ZZAL*00*!^^ ' N" e T '^ THE LIBRARY OF HAVERFORD COLLEGE THE GIFT OF / mo. &5 I 19 30 ^~ I 4" <~ ACCESSION NO. I ^ Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2011 with funding from LYRASIS Members and Sloan Foundation http://www.archive.org/details/haverfordcollege2728have C HAVERFORD COLLEGE DIRECTORY 1929-1930 HAVERFORD COLLEGE BULLETIN Vol. XXVIII September, 1929 No. 1 as Second Class Matter under Act ot *Entered December 10, 1902, at Haverford, Pa., Congress of July 16, 1894. Accepted for mailing at special rates of postage provided for in Section 1103. Act of October 3, 1917, authorized on July 3, 1918. FACULTY, OFFICERS, ETC. Name Address Telephone (Haverford unless (Ardmore Exchange otherwise noted) unless otherwise noted) Babbitt, Dr. James A 785 College Ave 50 Montgomery Inn, Barrett, Don C. Bryn Mawr 342 1222 Brown, Henry Tatnall, Jr., . 1 College Lane ^Carpenter, James McF., Jr.. Woodside Cottage 2467 Chase O. M Founders Hall, East 564 Comfort,' William W Walton Field 455 Dunn, Emmett R Apartment 21— Hamilton Court, Ardmore 4622 Evans. Arlington 324 Boulevard, Brookline, Upper Darby P. O., Pa. Hilltop 2043 J Elkins Ave., Phila., Pa. Flosdorf , E. W 612 Waverly 1919 Flight, J. W 629 Walnut Lane 1536 J *Grant, Elihu Oakley Road 186 *Gray, Austin K White Hall 3160 Gummere, Henry V - Lancaster Pike and Gordon Ave 4677 Haddleton, A. W 791 College Ave 203 J Harman, Harvey J 15 Woodbine Ave., Narberth, Narberth 2326 Heller, John L 330 Locust Ave., Ardmore 285 M Herndon, John G., Jr 108 School House Lane, Ardmore Ardmore 3469 J Hetzel, Theodore B 1 College Lane 4698 J Johnston, Robert J 22 Clearfield Rd., Oakmont, Pa., Hilltop 1361 W * Jones, Rufus M 2 College Circle 2777 Kelly, John A Founders Hall, East 564 Kelsey, Rayner W 753 College Avenue 2630 Kitchen, Paul Cliff 327 S.