The Ten String Quartets of Ben Johnston Are Among the Most Fascinating Collections of Work Ever Produced by an American Composer

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2012 02 20 Programme Booklet FIN

COMPOSITION - EXPERIMENT - TRADITION: An experimental tradition. A compositional experiment. A traditional composition. An experimental composition. A traditional experiment. A compositional tradition. Orpheus Research Centre in Music [ORCiM] 22-23 February 2012, Orpheus Institute, Ghent Belgium The fourth International ORCiM Seminar organised at the Orpheus Institute offers an opportunity for an international group of contributors to explore specific aspects of ORCiM's research focus: Artistic Experimentation in Music. The theme of the conference is: Composition – Experiment – Tradition. This two-day international seminar aims at exploring the complex role of experimentation in the context of compositional practice and the artistic possibilities that its different approaches yield for practitioners and audiences. How these practices inform, or are informed by, historical, cultural, material and geographical contexts will be a recurring theme of this seminar. The seminar is particularly directed at composers and music practitioners working in areas of research linked to artistic experimentation. Organising Committee ORCiM Seminar 2012: William Brooks (U.K.), Kathleen Coessens (Belgium), Stefan Östersjö (Sweden), Juan Parra (Chile/Belgium) Orpheus Research Centre in Music [ORCiM] The Orpheus Research Centre in Music is based at the Orpheus Institute in Ghent, Belgium. ORCiM's mission is to produce and promote the highest quality research into music, and in particular into the processes of music- making and our understanding of them. ORCiM -

The Ten String Quartets of Ben Johnston, Written Between 1951 and 1995, Constitute No Less Than an Attempt to Revolutionize the Medium

The ten string quartets of Ben Johnston, written between 1951 and 1995, constitute no less than an attempt to revolutionize the medium. Of them, only the First Quartet limits itself to conventional tuning. The others, climaxing in the astonishing Seventh Quartet of 1984, add in further microtones from the harmonic series to the point that the music seems to float in a free pitch space, unmoored from the grid of the common twelve-pitch scale. In a way, this is a return to an older conception of string quartet practice, since players used to (and often still do) intuitively adjust their tuning for maximum sonority while listening to each other’s intonation. But Johnston has extended this practice in two dimensions: Rather than leave intonation to the performer’s ear and intuition, he has developed his own way to specify it in notation; and he has moved beyond the intervals of normal musical practice to incorporate increasingly fine distinctions, up to the 11th, 13th, and even 31st partials in the harmonic series. This recording by the indomitable Kepler Quartet completes the series of Johnston’s quartets, finally all recorded at last for the first time. Volume One presented Quartets 2, 3, 4, and 9; Volume Two 1, 5, and 10; and here we have Nos. 6, 7, and 8, plus a small piece for narrator and quartet titled Quietness. As Timothy Ernest Johnson has documented in his exhaustive dissertation on Johnston’s Seventh Quartet, Johnston’s string quartets explore extended tunings in three phases.1 Skipping over the more conventional (though serialist) First Quartet, the Second and Third expand the pitch spectrum merely by adding in so-called five-limit intervals (thirds, fourths, and fifths) perfectly in tune (which means unlike the imperfect, compromised way we tune them on the modern piano). -

Free Jazz in the Classroom: an Ecological Approach to Music Educationi

David Borgo Free Jazz in the Classroom: An Ecological Approach to Music Educationi Abandon Knowledge About Knowledge All Ye Who Enter Here. Bruno Latourii Conventional Western educational practice hinges on the notion that knowledge— or at least knowledge worth having—is primarily conceptual and hence can be abstracted from the situations in which it is learned and used. I recently came across a helpful illustration of this general tendency while watching Monty Python reruns. The sketch involved a caricature of a British talk show called “How to Do It.” John Cleese served as the show’s host: Well, last week we showed you how to become a gynecologist. And this week on “How to Do It” we're going to show you how to play the flute, how to split an atom, how to construct a box girder bridge, how to irrigate the Sahara Desert and make vast new areas of land cultivatable, but first, here’s Jackie to tell you all how to rid the world of all known diseases. After Eric Idle solves the global health crisis in a sentence or two, John Cleese explains “how to play the flute”: “Well here we are. (Picking up a flute.) You blow there and you move your fingers up and down here.” Turning again to the camera, he concludes the show with a teaser for the next installment: Well, next week we’ll be showing you how black and white people can live together in peace and harmony, and Alan will be over in Moscow showing us how to reconcile the Russians and the Chinese. -

NEA-Annual-Report-1980.Pdf

National Endowment for the Arts National Endowment for the Arts Washington, D.C. 20506 Dear Mr. President: I have the honor to submit to you the Annual Report of the National Endowment for the Arts and the National Council on the Arts for the Fiscal Year ended September 30, 1980. Respectfully, Livingston L. Biddle, Jr. Chairman The President The White House Washington, D.C. February 1981 Contents Chairman’s Statement 2 The Agency and Its Functions 4 National Council on the Arts 5 Programs 6 Deputy Chairman’s Statement 8 Dance 10 Design Arts 32 Expansion Arts 52 Folk Arts 88 Inter-Arts 104 Literature 118 Media Arts: Film/Radio/Television 140 Museum 168 Music 200 Opera-Musical Theater 238 Program Coordination 252 Theater 256 Visual Arts 276 Policy and Planning 316 Deputy Chairman’s Statement 318 Challenge Grants 320 Endowment Fellows 331 Research 334 Special Constituencies 338 Office for Partnership 344 Artists in Education 346 Partnership Coordination 352 State Programs 358 Financial Summary 365 History of Authorizations and Appropriations 366 Chairman’s Statement The Dream... The Reality "The arts have a central, fundamental impor In the 15 years since 1965, the arts have begun tance to our daily lives." When those phrases to flourish all across our country, as the were presented to the Congress in 1963--the illustrations on the accompanying pages make year I came to Washington to work for Senator clear. In all of this the National Endowment Claiborne Pell and began preparing legislation serves as a vital catalyst, with states and to establish a federal arts program--they were communities, with great numbers of philanthro far more rhetorical than expressive of a national pic sources. -

Scanned Using Book Scancenter 5022

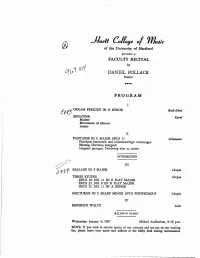

mu.die of the University of Hartford presents a FACULTY RECITAL by DANIEL POLLACK Pianist •••• PROGRAM I {!,ffJ ORGAN PRELUDE ING MINOR Bach..Siloti SONATINE Ravel Modere Mouvement de Menuet Anime II FANTAISIE IN C MAJOR OPUS 17 Schumann Durchaus fantastisch und leidenschaf tligh vorzutragen Maessig. Durchaus energisch Langsam g~ragen. Durchweg leise zu halten INTE.RMISSION / -: III ¿ ff t BALLADE IN F MAJOR Chopin TIIREE ETIJDES Chopin OPUS 10, NO. 11 IN E FLAT MAJOR OPUS 25, NO. a IN D FLAT MAJOR OPUS 25, NO. 11 IN A MINOR NOCTIJRNE IN C SHARP MINOR OPUS POSTHUMOUS Chopin IV MEPHISTO WAL1Z BALDWIN PIANO Wednesday, January 4, 1967 Millard Auditorium, 8: 30 p.m. NOTE: If you wish to receive notice of our concerts and are not on our mailing list, please leave your name and address at the lobby desk during intermission. - -··· -· ---------------------- . - . - ... .. -· - ·-~ A CONCERT OF MUSIC BY ARNOLD FRANCHETTI Thu.rsday, Jan:u.ary 12 at 8:30 P.M. PROGRAM -WAR BAI ..I,ADES PreI1.iiere Per:f or.11.-ian.ce ·1 Ballade by Kathleen Lombardo 2 and 3 Ballades by Elizabeth Randall-Mills Richard Provost, guitar Mary Collier*, soprano BRASS QUINTET Ronald Kutik, Roger Murtha, trumpet; Robert Meyers, James Roberts, trombone; Ronald Apperson, tuba Edward Mi I ler, conductor CONCERTINO Canzona Cuckoo Notturno Rondel lo Daniel Kobialka, '66, violin soloist Nancy Turetzky, alto flute, flute, piccolo; Bertram Turetzky, double bass; Tele Lesbines, percussion; Myron Press*, piano Henry Larsen, conductor INTERMISSION *Guest Artist I L -------------------------------------- . CONCERTO IN DO Preniiere Per:for1I1.an.ce IN TWO MOVEMENTS Commissioned by the Library of Congress, 1962, in memory of Natalie and Serge Koussevitzky. -

Curriculum Vitae

Curriculum Vitae Nathan E. Nabb, D.M. Associate Professor of Music – Saxophone Stephen F. Austin State University www.nathannabbmusic.com Contact Information: 274 Wright Music Building College of Fine Arts - School of Music Stephen F. Austin State University TEACHING EXPERIENCE Associate Professor of Saxophone Stephen F. Austin State University 2010 to present Nacogdoches, Texas Maintain and recruit private studio averaging 20+ music majors Applied saxophone instruction to saxophone majors (music education and performance) Saxophone quartets (number depending on enrollment) Private Applied Pedagogy and Repertoire for graduate saxophone students Recruitment tour performances and master classes with other wind faculty Saxophone studio class Assistant Professor of Saxophone Morehead State University 2005 to 2010 Morehead, Kentucky Maintain and recruit private studio averaging 17-22 music majors Applied saxophone instruction to saxophone majors (education, performance and jazz) Saxophone quartets (three or four depending on enrollment) Woodwind methods course (flute, clarinet and saxophone) Saxophone segment of Advanced Woodwind Methods Course Private Applied Pedagogy and Performance Practice for graduate saxophone students Guided independent study courses for graduate saxophone students Present annual clinics for Kentucky high-school saxophonists for the MSU Concert Band Clinic Present annual All-State audition preparation clinics Academic advisor for undergraduate private applied saxophonists Saxophone studio class Nathan E. Nabb Curriculum -

Too Many Notes: Complexity and Culture in Voyager����� Lewis, George E

Too Many Notes: Complexity and Culture in Voyager Lewis, George E. Leonardo Music Journal, Volume 10, 2000, pp. 33-39 (Article) Published by The MIT Press For additional information about this article http://muse.jhu.edu/journals/lmj/summary/v010/10.1lewis.html Access Provided by University of California @ Santa Cruz at 09/27/11 9:42PM GMT W A Y S WAYS & MEANS & M E A Too Many Notes: Computers, N S Complexity and Culture in Voyager ABSTRACT The author discusses his computer music composition, Voyager, which employs a com- George E. Lewis puter-driven, interactive “virtual improvising orchestra” that ana- lyzes an improvisor’s performance in real time, generating both com- plex responses to the musician’s playing and independent behavior arising from the program’s own in- oyager [1,2] is a nonhierarchical, interactive mu- pears to stand practically alone in ternal processes. The author con- V the trenchancy and thoroughness tends that notions about the na- sical environment that privileges improvisation. In Voyager, improvisors engage in dialogue with a computer-driven, inter- of its analysis of these issues with ture and function of music are active “virtual improvising orchestra.” A computer program respect to computer music. This embedded in the structure of soft- ware-based music systems and analyzes aspects of a human improvisor’s performance in real viewpoint contrasts markedly that interactions with these sys- time, using that analysis to guide an automatic composition with Catherine M. Cameron’s [7] tems tend to reveal characteris- (or, if you will, improvisation) program that generates both rather celebratory ethnography- tics of the community of thought complex responses to the musician’s playing and indepen- at-a-distance of what she terms and culture that produced them. -

View PDF Online

MARLBORO MUSIC 60th AnniversAry reflections on MA rlboro Music 85316_Watkins.indd 1 6/24/11 12:45 PM 60th ANNIVERSARY 2011 MARLBORO MUSIC Richard Goode & Mitsuko Uchida, Artistic Directors 85316_Watkins.indd 2 6/23/11 10:24 AM 60th AnniversA ry 2011 MARLBORO MUSIC richard Goode & Mitsuko uchida, Artistic Directors 85316_Watkins.indd 3 6/23/11 9:48 AM On a VermOnt HilltOp, a Dream is BOrn Audience outside Dining Hall, 1950s. It was his dream to create a summer musical community where artists—the established and the aspiring— could come together, away from the pressures of their normal professional lives, to exchange ideas, explore iolinist Adolf Busch, who had a thriving music together, and share meals and life experiences as career in Europe as a soloist and chamber music a large musical family. Busch died the following year, Vartist, was one of the few non-Jewish musicians but Serkin, who served as Artistic Director and guiding who spoke out against Hitler. He had left his native spirit until his death in 1991, realized that dream and Germany for Switzerland in 1927, and later, with the created the standards, structure, and environment that outbreak of World War II, moved to the United States. remain his legacy. He eventually settled in Vermont where, together with his son-in-law Rudolf Serkin, his brother Herman Marlboro continues to thrive under the leadership Busch, and the great French flutist Marcel Moyse— of Mitsuko Uchida and Richard Goode, Co-Artistic and Moyse’s son Louis, and daughter-in-law Blanche— Directors for the last 12 years, remaining true to Busch founded the Marlboro Music School & Festival its core ideals while incorporating their fresh ideas in 1951. -

The Composer's Guide to the Tuba

THE COMPOSER’S GUIDE TO THE TUBA: CREATING A NEW RESOURCE ON THE CAPABILITIES OF THE TUBA FAMILY Aaron Michael Hynds A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF MUSICAL ARTS August 2019 Committee: David Saltzman, Advisor Marco Nardone Graduate Faculty Representative Mikel Kuehn Andrew Pelletier © 2019 Aaron Michael Hynds All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT David Saltzman, Advisor The solo repertoire of the tuba and euphonium has grown exponentially since the middle of the 20th century, due in large part to the pioneering work of several artist-performers on those instruments. These performers sought out and collaborated directly with composers, helping to produce works that sensibly and musically used the tuba and euphonium. However, not every composer who wishes to write for the tuba and euphonium has access to world-class tubists and euphonists, and the body of available literature concerning the capabilities of the tuba family is both small in number and lacking in comprehensiveness. This document seeks to remedy this situation by producing a comprehensive and accessible guide on the capabilities of the tuba family. An analysis of the currently-available materials concerning the tuba family will give direction on the structure and content of this new guide, as will the dissemination of a survey to the North American composition community. The end result, the Composer’s Guide to the Tuba, is a practical, accessible, and composer-centric guide to the modern capabilities of the tuba family of instruments. iv To Sara and Dad, who both kept me going with their never-ending love. -

Liner Notes, Visit Our Web Site

The World’s Longest Melody is the title of this CD, the sixth to date devoted entirely to Larry Polansky’s music, and, curiously, the title of not one but two of the pieces on it: The World’s Longest Melody (Ensemble), and “The World’s Longest Melody (Trio): ‘The Ever-Widening Halfstep’”, the final piece of for jim, ben and lou. On casual listening, the two pieces seem to bear little relationship to each other. In fact, “The World’s Longest Melody” is a generic title, which referred originally to a simple but powerful theoretical melodic algorithm that Polansky devised and first published in a set of pieces called Distance Musics in the mid-1980s; the title then became attached both to the software itself (several generations thereof) as well as to a number of compositions of radically different form and character that resulted from its use. This situation shows something of the nature of Polansky’s musical and conceptual world, where ideas constantly grow, mutate, and branch out in unexpected directions. There are no clear lines of demarcation between his activities as composer, performer, improviser, theorist, computer musician, teacher, publisher, editor, musicologist: Polansky’s whole artistic endeavor might be thought of as a search for ways of participating responsibly in the complexity and plenitude of the world, and of sharing its abundance with others. The guitar has long been an important component in Polansky’s musical explorations, and this CD has grown from the enthusiasm for his work by the musicians of the Belgian electric guitar quartet ZWERM. -

Summer Institute

AMERICAN SOCIETY OF UNIVERSITY COMPOSERS SUMMER INSTITUTE Presented in Cooperation with THE UNIVERSITY OF ILLINOIS SCHOOL OF MUSIC THE KRANNERT CENTER FOR THE PERFORMING ARTS And With the Assistance of The Alice M. Ditson Fund The Fromm Foundation The Quincy Foundation AUGUST 9-14, 1970 Events to be held at: Allerton House, Monticello, Illinois The Krannert Center for the Performing Arts, Urbana, Illinois Smith Music Hall, Urbana, Illinois Teaching Staff: JAMES BEAUCHAMP EDWARD KOBRIN CHARLES BRAUGHAM EDWIN LONDON BENJAMIN JOHNSTON THOMAS SiwE Composers in Residence: DAVID BURGE WENDELL LOGAN GEORGE BURT DONALD MARTINO BARNEY CHILDS SALVATORE MARTIRANO RANDOLPH COLEMAN ELLIOTT ScHwARTZ SIDNEY HODKINSON PAUL ZoNN M. WILLIAM KARLINS Students are invited to solicit private conferences with Resident Composers All events are at Allerton House unless otherwise specified SCHEDULE OF EVENTS SUNDAY, AUGUST 9, 1970 4:00 p.m., Smith Music Hall Program of University of Illinois Student Composers 8:00 p.m. Electronic Music Program presented by Experimental Music Studio, University of Illinois JAMES BEAUCHAMP, Director MONDAY, AUGUST 10, 1970 9:00 a.m. to 11 :00 a.m. "The Computer as Composer: (1) Programming" EDWARD KOBRIN 1 :00 p .m. to 3 :00 p .m. "Survey of Percussion Instruments" THOMAS SiwE 3 :00 p.m. to 5 :00 p.m. Open reading and recording of selected student compositions University of Illinois Contemporary Chamber Players EDWIN LONDON, Director 7 :30 p.m. to 9 :30 p.m. Lecture: "Problems of Notation and Autography" by DONALD MARTINO Panel Discussion: BENJAMIN JOHNSTON, moderator, BARNEY CHILDS, ELLIOTT SCHWARTZ, RANDOLPH COLEMAN TUESDAY, AUGUST 11, 1970 9 :00 a.m. -

Dissertation 3.19.2021

Cultivating the Contemporary Clarinetist: Pedagogical Materials for Extended Clarinet Techniques Caitlin Beare A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts University of Washington 2021 Reading Committee: Timothy Salzman, Chair David Rahbee Benjamin Lulich Program Authorized to Offer Degree: Music © Copyright 2021 Caitlin Beare University of Washington Abstract Cultivating the Contemporary Clarinetist: Pedagogical Materials for Extended Clarinet Techniques Caitlin Beare Chair of the Supervisory Committee: Timothy Salzman School of Music The exploration and implementation of new timbral possibilities and techniques over the past century have redefined approaches to clarinet performance and pedagogy. As the body of repertoire involving nontraditional, or “extended,” clarinet techniques has grown, so too has the pedagogical literature on contemporary clarinet performance, yielding method books, dissertations, articles, and online resources. Despite the wealth of resources on extended clarinet techniques, however, few authors offer accessible pedagogical materials that function as a gateway to learning contemporary clarinet techniques and literature. Consequently, many clarinetists may be deterred from learning a significant portion of the repertoire from the past six decades, impeding their musical development. The purpose of this dissertation is to contribute to the pedagogical literature pertaining to extended clarinet techniques. The document consists of two main sections followed by two appendices. The first section (chapters 1-2) contains an introduction and a literature review of extant resources on extended clarinet techniques published between 1965–2020. This literature review forms the basis of the compendium of materials, found in Appendix A of this document, which aims to assist performers and teachers in searching for and selecting pedagogical materials involving extended clarinet techniques.