Lehigh Preserve Institutional Repository

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Pick up a Trollope ~ 1

A selection of excerpts from the novels of Anthony Trollope chosen by notable Trollopians Vote for your favourite and join us online to read the winning novel. Pick Up A Trollope ~ 1 Pick Up A Trollope Perhaps more than any other writer of the Victorian era, Anthony Trollope wrote novels that transcend the time and place of their writing so that they speak to a 21st Century audience as eloquently as they addressed their first readers 150 years ago. For me, the reason why this is so is evident – Trollope wrote about characters who are real, who engage our sympathies in spite of, indeed I would argue, because of their flaws. No hero is without his feet of clay; no heroine perfectly fits that Victorian archetype “the Angel of the Hearth” and no villain is without redeeming feature, be it courage or compassion, shown at a key moment in the story. Examples of just such flawed, and therefore more believable, characters abound in the selections included here. Whether it be Melmotte, the prescient depiction of the unscrupulous financier, inThe Way We Live Now (was ever a book so aptly named?), or the conscience-stricken Lady Mason of Orley Farm, or Madeline Neroni, the apparently heartless femme fatale playing out her schemes in Barchester Towers, all live in the mind of the reader after the pages of the book are closed. This, I attribute to Trollope’s acute powers of observation, honed through years of feeling an outsider on the fringes of the society in which he moved, which enabled him to reveal through almost imperceptible nuances insights into even the humblest of his characters. -

Men, Women, and Property in Trollope's Novels Janette Rutterford

Accounting Historians Journal Volume 33 Article 9 Issue 2 December 2006 2006 Frank must marry money: Men, women, and property in Trollope's novels Janette Rutterford Josephine Maltby Follow this and additional works at: https://egrove.olemiss.edu/aah_journal Part of the Accounting Commons, and the Taxation Commons Recommended Citation Rutterford, Janette and Maltby, Josephine (2006) "Frank must marry money: Men, women, and property in Trollope's novels," Accounting Historians Journal: Vol. 33 : Iss. 2 , Article 9. Available at: https://egrove.olemiss.edu/aah_journal/vol33/iss2/9 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Archival Digital Accounting Collection at eGrove. It has been accepted for inclusion in Accounting Historians Journal by an authorized editor of eGrove. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Rutterford and Maltby: Frank must marry money: Men, women, and property in Trollope's novels Accounting Historians Journal Vol. 33, No. 2 December 2006 pp. 169-199 Janette Rutterford OPEN UNIVERSITY INTERFACES and Josephine Maltby UNIVERSITY OF YORK FRANK MUST MARRY MONEY: MEN, WOMEN, AND PROPERTY IN TROLLOPE’S NOVELS Abstract: There is a continuing debate about the extent to which women in the 19th century were involved in economic life. The paper uses a reading of a number of novels by the English author Anthony Trollope to explore the impact of primogeniture, entail, and the mar- riage settlement on the relationship between men and women and the extent to which women were involved in the ownership, transmission, and management of property in England in the mid-19th century. INTRODUCTION A recent Accounting Historians Journal article by Kirkham and Loft [2001] highlighted the relevance for accounting history of Amanda Vickery’s study “The Gentleman’s Daughter.” Vickery [1993, pp. -

THE TROLLOPE CRITICS Also by N

THE TROLLOPE CRITICS Also by N. John Hall THE NEW ZEALANDER (editor) SALMAGUNDI: BYRON, ALLEGRA, AND THE TROLLOPE FAMILY TROLLOPE AND HIS ILLUSTRATORS THE TROLLOPE CRITICS Edited by N. John Hall Selection and editorial matter © N. John Hall 1981 Softcover reprint of the hardcover 1st edition 1981 978-0-333-26298-6 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without permission First published 1981 by THE MACMILLAN PRESS LTD London and Basingstoke Companies and representatives throughout the world ISBN 978-1-349-04608-9 ISBN 978-1-349-04606-5 (eBook) DOI 10.1007/978-1-349-04606-5 Typeset in 10/12pt Press Roman by STYLESET LIMITED ·Salisbury· Wiltshire Contents Introduction vii HENRY JAMES Anthony Trollope 21 FREDERIC HARRISON Anthony Trollope 21 w. P. KER Anthony Trollope 26 MICHAEL SADLEIR The Books 34 Classification of Trollope's Fiction 42 PAUL ELMER MORE My Debt to Trollope 46 DAVID CECIL Anthony Trollope 58 CHAUNCEY BREWSTER TINKER Trollope 66 A. 0. J. COCKSHUT Human Nature 75 FRANK O'CONNOR Trollope the Realist 83 BRADFORD A. BOOTH The Chaos of Criticism 95 GERALD WARNER BRACE The World of Anthony Trollope 99 GORDON N. RAY Trollope at Full Length 110 J. HILLIS MILLER Self and Community 128 RUTH apROBERTS The Shaping Principle 138 JAMES GINDIN Trollope 152 DAVID SKILTON Trollopian Realism 160 C. P. SNOW Trollope's Art 170 JOHN HALPERIN Fiction that is True: Trollope and Politics 179 JAMES R. KINCAID Trollope's Narrator 196 JULIET McMASTER The Author in his Novel 210 Notes on the Authors 223 Selected Bibliography 226 Index 243 Introduction The criticism of Trollope's works brought together in this collection has been drawn from books and articles published since his death. -

Download Miss Mackenzie, Anthony Trollope, Chapman and Hall, 1868

Miss Mackenzie, Anthony Trollope, Chapman and Hall, 1868, , . DOWNLOAD http://bit.ly/1boZHoo Ayala's Angel (Sparklesoup Classics) , Anthony Trollope, Dec 5, 2004, , . Sparklesoup brings you Trollope's classic. This version is printable so you can mark up your copy and link to interesting facts and sites.. Orley Farm , Anthony Trollope, 1935, Fiction, 831 pages. This story deals with the imperfect workings of the legal system in the trial and acquittal of Lady Mason. Trollope wrote in his Autobiography that his friends considered this .... The Toilers of the Sea , Victor Hugo, 2000, Fiction, 511 pages. On the picturesque island of Guernsey in the English Channel, Gilliatt, a reclusive fisherman and dreamer, falls in love with the beautiful Deruchette and sets out to salvage .... The Way We Live Now Easyread Super Large 18pt Edition, Anthony Trollope, Dec 11, 2008, Family & Relationships, 460 pages. The Duke's Children , Anthony Trollope, Jan 1, 2004, Fiction, . The sixth and final novel in Trollope's Palliser series, this 1879 work begins after the unexpected death of Plantagenet Palliser's beloved wife, Lady Glencora. Though wracked .... He Knew He Was Right , Anthony Trollope, Jan 1, 2004, Fiction, . Written in 1869 with a clear awareness of the time's tension over women's rights, He Knew He Was Right is primarily a story about Louis Trevelyan, a young, wealthy, educated .... Framley Parsonage , Anthony Trollope, Jan 1, 2004, Fiction, . The fourth work of Trollope's Chronicles of Barsetshire series, this novel primarily follows the young curate Mark Robarts, newly arrived in Framley thanks to the living .... Ralph the Heir , Anthony Trollope, 1871, Fiction, 434 pages. -

The Duke's Children, Notes on Selected Restored Passages

The Duke’s Children, Notes on Selected Restored Passages | Amarnick, last revised April 9, 2017 CHAPTER 1 1) When this sad event happened he had ceased to be Prime Minister just two years. Those who are conversant with the political changes which have taken place of late in the government of…yet returned to office. Trollope provides reassurance that we don’t need to remember, or even to have read, the earlier novels in the series; he will tell us what we must know to become “conversant.” On the other hand, he also offers incentives to acquaint or re-acquaint ourselves with those earlier books. As he had written in An Autobiography about the Duke and the Duchess (originally Plantagenet Palliser and Glencora M‘Cluskie) immediately before he wrote The Duke’s Children in 1876: That the man’s character should be understood as I understand it—or that of his wife, the delineation of which has also been a matter of much happy care to me—I have no right to expect, seeing that the operation of describing has not been confined to one novel, which might perhaps be read through by the majority of those who commenced it. It has been carried on through three or four, each of which will be forgotten even by the most zealous reader almost as soon as read. In The Prime Minister, my Prime Minister will not allow his wife to take office among, or even over, those ladies who are attached by office to the Queen’s Court. “I should not choose,” he says to her, “that my wife should have any duties unconnected with our joint family and home.” Who will remember in reading those words that in a former story, published some years before, he tells his wife, when she has twitted him with his willingness to clean the Premier’s shoes, that he would even allow her to clean them if it were for the good of the country? And yet it is by such details as these that I have, for many years past, been manufacturing within my own mind the characters of the man and his wife. -

Dissent Women in Anthony Trollope's Fiction: a Sympathetic Portrayal

UNLV Retrospective Theses & Dissertations 1-1-1993 Dissent women in Anthony Trollope's fiction: A sympathetic portrayal Elisabeth Morton McLaren University of Nevada, Las Vegas Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalscholarship.unlv.edu/rtds Repository Citation McLaren, Elisabeth Morton, "Dissent women in Anthony Trollope's fiction: A sympathetic portrayal" (1993). UNLV Retrospective Theses & Dissertations. 2982. http://dx.doi.org/10.25669/uqts-wcbg This Dissertation is protected by copyright and/or related rights. It has been brought to you by Digital Scholarship@UNLV with permission from the rights-holder(s). You are free to use this Dissertation in any way that is permitted by the copyright and related rights legislation that applies to your use. For other uses you need to obtain permission from the rights-holder(s) directly, unless additional rights are indicated by a Creative Commons license in the record and/or on the work itself. This Dissertation has been accepted for inclusion in UNLV Retrospective Theses & Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Digital Scholarship@UNLV. For more information, please contact [email protected]. INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced frommicrofilm the master, UMI film s the text directly from theoriginal or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent uponq u a lity theof the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandardmargins, and improper alignment can adversely afreet reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. -

Political and Household Governance in Anthony Trollope's Palliser Novels

A “WOMAN’S BEST RIGHT”—TO A HUSBAND OR THE BALLOT?: POLITICAL AND HOUSEHOLD GOVERNANCE IN ANTHONY TROLLOPE’S PALLISER NOVELS LINDA C. MCCLAIN ABSTRACT The year 2020 marks the one hundredth anniversary of the ratification of the Nineteenth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution. In 2018, the United Kingdom marked the one hundredth anniversary of some women securing the right to vote in parliamentary elections and the ninetieth anniversary of women securing the right to vote on the same terms as men. People observing the Nineteenth Amendment’s centenary may have difficulty understanding why it required a lengthy campaign of nearly a century to secure the right of women to vote. One influential rationale in both the United Kingdom and the United States was domestic gender ideology about men’s and women’s separate spheres and destinies. This ideology included the societal premise where the husband was the legal and political representative of the household and extending women’s rights—whether in the realm of marriage or of political life—would disrupt domestic and political order. This Article argues that an illuminating window on how such gender ideology bore on the struggle for women’s political rights is the mid-Victorian British author Anthony Trollope’s famous political novels, the Palliser series. These novels overlap with the pioneering phase of the women’s rights campaign in Britain and a key period of legislative debates over Robert Kent Professor of Law, Boston University School of Law. Thanks very much to Kimberley Bishop, Collin Grier, Chase Shelton, and and the editors of the Boston University Law Review for their careful editing of this Article. -

ANTHONY TROLLOPE the Warden and Barchester Towers

ANTHONY TROLLOPE The Warden and Barchester Towers Alice Elzinga The publication of, Trollope, A Commentary, by Michael Sadlier in・ 1927,.and Revised Edition in 1947, did, much to re-establish Trollope's reputation. Sadlier claimed that Trollope was the' true historian of the mid-Victorian era of the 50's through the 70's. Of these mid-Victorians, he s' ≠奄пG“一who lived their lives in contented and industrious well-being一一一一who from principle alone and by selfdenial strove to fulfill their own high standard of personal integrity.” Furthetmore, Trollope is also the “mouthpiece” of family struggles and agonies as a result of the strict social ladder during that p eriod of England's history. “Is he a gentleman-does he/she own an estate is he/she a pure-blood Englishman of the a.ristocracy-will he/she inherit a title一一?” these were questions upper most in the minds of parents who had sons/daughters of marriageable age. Trollope血akes his readers feel and live these family agonies. The revival of Trollope 'has been variously explained. lt need not be emphasized in this article because it was the emphasis in my first article on T.rollope. However, the question is more than academically'interesting. He has thrust his way through the wall of oblivion, as he used to thrust at a fence he could hardly see. And he cOmes back, not as a period piece, (though no one haS given us so pungent an aroma of the rect6ry dir血groom, the parlour bf genteel poverty, the country town,) but as a novelist to be' assessed, perhaps at a higher rate than his own time ultimately -

Anthony Trollope*S Literary Reputation;

ANTHONY TROLLOPE*S LITERARY REPUTATION; ITS DEVELOPMENT AND VALIDITY by ELLA KATHLEEN GRANT A Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for. the Degree of Master of Arts in the Department of English The University of British Columbia, October, 1950. This essay attempts to trace the course of Anthony Trollope's literary reputation; to suggest some explan• ations for the various spurts and sudden declines of his popularity among readers and esteem among critics; and to prove that his mid-twentieth century position is not a just one. Drawing largely on Trollope's Autobiography, contemp• orary reviews and essays on his work, and references to it in letters and memoirs, the first chapter describes Trollope's writing career, showing him rising to popu• larity in the late fifties and early sixties as a favour• ite among readers tired of sensational fiction, becoming a byword for commonplace mediocrity in the seventies, and finally, two years before his death, regaining much of his former eminence among older readers and conservative critics. Throughout the chapter a distinction is drawn between the two worlds with which Trollope deals, Barset- shire and materialist society, and the peculiarly dual nature of his work is emphasized. Chapter II is largely concerned with the vicissitudes that Trollope's reputation has encountered since the post• humous publication of his autobiography. During the de• cade following his death he is shown as an object of comp• lete contempt to the Art for Art's Sake school, finally rescued around the turn of the century by critics reacting against the ideals of his detractors. -

Mill, Trollope and the Law

Law Text Culture Volume 1 Article 8 1994 "The woman business" : Mill, Trollope and the law C. Higgins Follow this and additional works at: https://ro.uow.edu.au/ltc Recommended Citation Higgins, C., "The woman business" : Mill, Trollope and the law, Law Text Culture, 1, 1994, 63-80. Available at:https://ro.uow.edu.au/ltc/vol1/iss1/8 Research Online is the open access institutional repository for the University of Wollongong. For further information contact the UOW Library: [email protected] "The woman business" : Mill, Trollope and the law Abstract Consideration of the legal, social and economic status of women and associated debate about the very nature of woman and her proper sphere, dismissively labelled "the Woman Business" by Thomas Carlyle, became a major preoccupation in mid-Victorian thought and writing and central to the legal and social refonns that gradually took place in the second half of the century. As Barickman et. al. point out, rather than being "a debate" per se, it was rather a set of issues, impulses, preoccupations - a pervasive social climate of questioning and change that eventually reached into every class and affected, however slowly, nearly every relationship between men and women in nineteenth-century England. This journal article is available in Law Text Culture: https://ro.uow.edu.au/ltc/vol1/iss1/8 law/text/culture ~ITHE WOMAN BUSINESS": a~ TROLLOPE AND THE Christine Higgins onsideration of the legal, social and economic status of women and associated debate about the very nature of woman and her proper Csphere, dismissively labelled "the Woman BusinessH by Thomas Carlyle, became a major preoccupation in mid-Victorian thought and writing and central to the legal and social refonns that gradually took place in the second halfofthe century. -

Deborah Denenholz Morse September 2020

Deborah Denenholz Morse September 2020 Office Address: Tucker Hall 230 email: [email protected]; cell: 757-870-3811 Home Address: 103 Robert Elliffe Rd., Williamsburg, VA 23185 ACADEMIC POSITIONS Inaugural Sara E. Nance Eminent Professor of English, William & Mary, 2017-present Vera W. Barkley Term Professor of English, William & Mary, 2014-16 Inaugural Fellow, Center for the Liberal Arts, William & Mary, Jan 2014-May 2016 Professor of English, William & Mary, 2008-present Inaugural University Professor for Teaching Excellence, William & Mary, 1996-1999 Associate Professor of English, William & Mary, 1994-2007 Assistant Professor of English, William & Mary, 1988-1994 Lecturer, University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee, 1983-1988 Teaching Fellow, Northwestern University, 1976-1978 Position at Present: Sara E. Nance Eminent Professor of English, William & Mary EDUCATION Ph.D., English Literature, Northwestern University, 1986 M.A., English Literature, Northwestern University, 1977 B.A., English Literature, Stanford University, 1974 HONORS, PRIZES, AND AWARDS Since 2013 Feb 2020 Invited Great Courses/Audible Brontë Lectures; Recording February 2021 ($12,000) Oct. 2019 Invited Tack Faculty Lecture, W & M and community Mar 2019 Invited Distinguished Lecturer. Centre for the Novel. University of Aberdeen, Scotland. Mar 2019 Invited Lecturer. St. Andrews Exchange Program. St. Andrews, Scotland. Oct 2018 Invited Inaugural Sara E. Nance Lecture. William & Mary English Department;100 Years of Women at William & Mary. Sept. 2018 Advisor Award, First Prize Essay, International Anthony Trollope Prize Competition, Undergraduate Division. 1 June 2018 Selected Guest Editor, Anne Brontë Bicentenary Issue, Victorians: Journal of Culture and Literature, Fall 2020, Double Issue. Apr 2018 Invited editorship, Cambridge University Press, The Complete Works of The Brontës. -

Appendix II Bibliography of Anthony Trollope

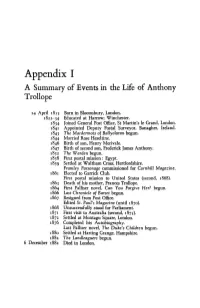

Appendix I A Summary of Events in the Life of Anthony Trollope 24 April 1815 Born in Bloomsbury, London. 1822-34 Educated at Harrow; Winchester. 1834 Joined General Post Office, StMartin's le Grand, London. 1841 Appointed Deputy Postal Surveyor, Banagher, Ireland. 1843 The Macdermots of Ballycloran begun. 1844 Married Rose Heseltine. 1846 Birth of son, Henry Merivale. 1847 Birth of second son, Frederick James Anthony. 1852 The Warden begun. 1858 First postal mission: Egypt. 1859 Settled at Waltham Cross, Hertfordshire. Framley Parsonage commissioned for Cornhill Magazine. 1861 Elected to Garrick Club. First postal mission to United States (second, 1868). 1863 Death of his mother, Frances Trollope. 1864 First Palliser novel, Can You Forgive Her? begun. 1866 Last Chronicle of Barset begun. 1867 Resigned from Post Office. Edited St. Paul's Magazine (until187o). 1868 Unsuccessfully stood for Parliament. 1871 First visit to Australia (second, 1875). 1872 Settled at Montagu Square, London. 1876 Completed his Autobiography. Last Palliser novel, The Duke's Children begun. 188o Settled at Harting Grange, Hampshire. 1882 The Landleagu.ers begun. 6 December 1882 Died in London. Appendix II Bibliography of Anthony Trollope (i) MAJOR WORKS The Macdermots of Ballydoran, 3 vols, London: T. C. Newby, 1847 [abridged in one volume, Chapman & Hall's 'New Edition', 1861]. The Kellys and the O'Kellys: or Landlords and Tenants, 3 vols, London: Henry Colburn, 1848. La Vendee: An Historical Romance, 3 vols, London: Colburn, 185o. The Warden, 1 vol, London: Longman, 1855. Barchester Towers, 3 vols, London: Longman, 1857. The Three Clerks: A Novel, 3 vols, London: Bentley, 1858.