This Article Appeared in a Journal Published by Elsevier. the Attached

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Golden Eagle Trans-Siberian Express Via the BAM and Yakutsk

Golden Eagle Trans-Siberian Express via the BAM and Yakutsk https://www.irtsociety.com/journey/golden-eagle-trans-siberian-express-bam-line/ Overview The Highlights - Explore smaller and remote towns of Russia, rarely visited by tourists - Grand Moscow’s Red Square, the Kremlin Armoury Chamber, St. Basil's Cathedral and Cafe Pushkin - Yekaterinburg, infamous execution site of Tsar Nicholas II, his wife Alexandra, their son, daughters and servants, by the Bolsheviks in 1918 - Fantastic Sayan Mountain scenery, including the Dzheb double horse-shoe curves The Society of International Railway Travelers | irtsociety.com | (800) 478-4881 Page 1/7 - Visit one of the biggest hydro-electric dams in the world in Bratsk and one of the world’s largest open cast mines in Neryungri - Stop at the unique and mysterious 3.7-mile (6km) long Chara Sand Dunes - Learn about the history and building of the BAM line at the local museum in Tynda - Marvel at Komsomolsk's majestic and expansive urban architecture of the Soviet era, including the stupendous Pervostroitelei Avenue, lined with Soviet store fronts and signage intact - City tour of Vladivostok, including a preserved World War II submarine - All meals, fine wine with lunch and dinner, hotels, gratuities, off-train tours and arrival/departure transfers included The Tour Travel by private train through an outstanding area of untouched natural beauty of Siberia, along the Baikal-Amur Magistral (BAM) line, visiting some of the lesser known places and communities of remote Russia. The luxurious Golden Eagle will transport you from Moscow to Vladivostok along the less-traveled, northerly Trans-Siberian BAM line. -

A Tool for Reconstruction of the Late Pleistocene (MIS 3) Palaeoenvironment of the Bol'shoj Naryn Site Area (Fore-Baikal Region, Eastern Siberia, Russia)

Quaternary International xxx (2014) 1e10 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Quaternary International journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/quaint The molluscs record: A tool for reconstruction of the Late Pleistocene (MIS 3) palaeoenvironment of the Bol'shoj Naryn site area (Fore-Baikal region, Eastern Siberia, Russia) * Guzel Danukalova a, b, , Eugeniya Osipova a, Fedora Khenzykhenova c, Takao Sato d a Institute of Geology, Ufa Scientific Center RAS, Ufa, Russia b Kazan Federal University, Kazan, Russia c Geological Institute, Siberian Branch RAS, Ulan-Ude, Russia d Department of Archaeology and Ethnology, Faculty of Letters, Keio University, Tokyo, Japan article info abstract Article history: A representative mollusc fauna attributed to the late phase of the Karginian Interstadial (MIS 3) has been Available online xxx found in the Bol'shoj Naryn Palaeolithic site (Fore-Baikal region). The general organization of the strata at the Bol'shoj Naryn site has been established through excavations realized during the previous field Keywords: seasons. It shows a modern soil made of sandy loess deposits 1 m thick, dated from the Sartan glacial Terrestrial molluscs stage, and underlined by a high viscosity paleosol layers which is up to 1 m thick developed during the Late Pleistocene Karginian Interstadial. The “cultural layer” has been correlated with the upper Karginian soil contains Karginian Interstadial numerous stone tools and animal fossils. This paper focus on the mollusc assemblage attributed to the Fore-Baikal region upper Karginian sediment. The mollusc assemblage (2460 determined specimens) consists of six species and five genera of terrestrial molluscs. Succinella oblonga, Pupilla muscorum and Vallonia tenuilabris are the best represented species. -

Lake Baikal Experience and Lessons Learned Brief

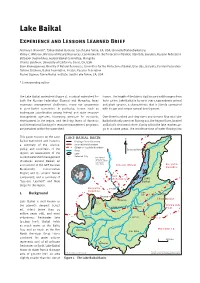

Lake Baikal Experience and Lessons Learned Brief Anthony J. Brunello*, Tahoe-Baikal Institute, South Lake Tahoe, CA, USA, [email protected] Valery C. Molotov, Ministry of Natural Resources, Committee for the Protection of Baikal, Ulan Ude, Buryatia, Russian Federation Batbayar Dugherkhuu, Federal Baikal Committee, Mongolia Charles Goldman, University of California, Davis, CA, USA Erjen Khamaganova, Ministry of Natural Resources, Committee for the Protection of Baikal, Ulan Ude, Buryatia, Russian Federation Tatiana Strijhova, Baikal Foundation, Irkutsk, Russian Federation Rachel Sigman, Tahoe-Baikal Institute, South Lake Tahoe, CA, USA * Corresponding author The Lake Baikal watershed (Figure 1), a critical watershed for France. The length of the lake is 636 km and width ranges from both the Russian Federation (Russia) and Mongolia, faces 80 to 27 km. Lake Baikal is home to over 1,500 endemic animal enormous management challenges, many not uncommon and plant species, a characteristic that is closely connected in post-Soviet economies. In particular, issues such as with its age and unique natural development. inadequate coordination among federal and state resource management agencies, increasing pressure for economic Over three hundred and sixty rivers and streams fl ow into Lake development in the region, and declining levels of domestic Baikal with only one river fl owing out, the Angara River, located and international funding for resource management programs, on Baikal’s northwest shore. Clarity within the lake reaches 40- are -

The Angara Triangle Sia , Located in South-Eastern Siberia in the Basins of Angara River, Lena, and Bratsk Severobaikalsk Nizhnyaya Tunguska Rivers

IRKUTSK REGION WELCOMES YOU Irkutsk Region (Russian: “Иркутская область”, Irkutskaya oblast) is regional administrative unit within Siberian Federal District of Rus- The Angara Triangle sia , located in south-eastern Siberia in the basins of Angara River, Lena, and Bratsk SeveroBAIKALsk Nizhnyaya Tunguska Rivers. The admin- istrative center is the city of Irkutsk. Russian presence in the area dates back to the 17th century, as the Russian Tsardom expanded eastward following the conquest of the Khanate of Sibir in 1582. By the end of the 17th century Irkutsk was a small town. Since the 18th century in Irkutsk the trades and crafts began to develop, the gold and silver craftsmen, smiths appeared, the town grew up to become soon the center of huge Irkutsk Province from where even former `Alaska was governed. Irkutsk The Angara Triangle f you live in the United States or in India , then With no doubt the Angara river is a gem of Eastern Si- the word “Angara” can bring instant images either beria which value is hard to overestimate. It is the river of of Senator Ed Angara calling for the shift to re- true love appreciated by the native Siberian, and this An- I newable energy and supporting green jobs, or the gara Gem is not just a physical stretch of river banks or a Tandoori chicken cooked over red hot coal called “anga- huge surrounding terrain. It is an ancient ethno-genetic ra” in classic Indian restaurant . One may also remember landscape of living of the native people and settled Russians an important character in the “Mahabharata-Krishna” of Siberia. -

Crossability of Pinus Sibirica and P. Pumila with Their Hybrids

Vasilyeva et. al.·Silvae Genetica (2013) 62/1-2, 61-68 KLASNJA, S., S. KOPITOVIC and S. ORLOVIC (2003): Variabil- melampsora leaf rust resistance in full-sib families of ity of some wood properties of eastern cottonwood (Pop- Populus. Silvae Genetica 43 (4): 219–226. ulus deltoides Bartr.) clones. Wood Sci. Tech. 37: REDEI, K. (2000): Early performance of promising white 331–337. poplar (Populus alba) clones in sandy ridges between KOUBAA, A., R. E. HERNANDEZ and M. BEAUDOIN (1998): the rivers Danube and Tisza in Hungary. Forestry Shrinkage of fast growing hybrid poplar clones. For. 73(4): 407–413. Prod. J. 48: 82–87. RIEMENSCHNEIDER, D. E., B. E. MCMAHON and M. E. OSTRY LIEVEN, D. B., V. DRIES, V. A. JORIS and S. MARC (2007): (1994): Population-dependent selection strategies need- End-use related physical and mechanical properties of ed for 2-year-old black cottonwood clones. Can J. For. selected fast-growing poplar hybrids (Populus tri- Res. 24: 1704–1710. chocarpa ϫ P. deltoides). Ann. For. Sci. 64: 621–630. SAS INSTITUE INC (1999): SAS/STAT user’s guide, Version O’NEIL, M. K., C. C. SHOCK and K. A. LOMBARD (2010): 8. SAS Institute Inc, Cary, NC, USA. Hybrid poplar (Populus ssp.) selections for arid and STEENACKERS, J., M. STEENACKERS, V. STEENACKERS and semi-arid intermountain regions of the western United M. STEVENS (1996): Poplar diseases, consequences on States. Agroforestry Syst 79: 409–418. growth and wood quality. Biomass Bioenergy 10: QIN, G. H., Y. Z. JIANG and Y. L. QIAO (2003): Study on the 267–274. -

Baikal Lake-Types of Landscapes in the Geographical Area

Lakes, reservoirs and ponds, vol. 3(1): 65-73, 2009 ©Romanian Limnogeographical Association BAIKAL LAKE-TYPES OF LANDSCAPES IN THE GEOGRAPHICAL AREA Ionuţ POPA TERRA MAGAZIN Review [email protected] Abstract The Baikal lake is located in Central Asia, on Russian Federation territory, in the southern part of East Siberia, on the border between Irkutsk Region and the Buryat Autonomous Republic. The lake surface lies between 51˚ 29’ lat. N, extreme south point, and 55˚ 46’ lat. N, in north, and between 103˚ 43’ long. E, extreme west point and 109˚ 56’ long E, in the east.His elongated shape is orientated on NE-SV direction, having a 636 km maximum length; the length of the shoreline is around 2 000 km. The maximum width is 79.5 km, in the sector where Barguzin river flows into the Baikal Lake, between the villages of Onguren, in west, and Oust Barguzin, in east, and the minimum width is only 25 km, in the area of Selenga river delta.Today, the total surface of the Baikal is 31 722 km2, with 500 km2 wider, after the rising of the Irkutsk dam, on Angara river. Keyword: lake, history, genesis, morphometry, landscape 1. Introduction Baikal Lake is the world deepest lake: 1637 m. The maximum sounded depth of 1642 m was measured by Hydrographic Service of Central Administration of Navigation and Oceanography and shown at the map “Lake Baikal”, scale 1 : 500 000, published in 1992. Considering that the lake surface is at 455.5 m above sea level, the deepest point of Baikal Lake is at 1186.5 m below sea level. -

Surface Temprature Dynamics of Lake Baikal Observed from AVHRR

PEER.REVIEWED ARTICI.E SurfaceTemperature Dynamics of LakeBaikal Observedfrom AVHRR lmages DavidW. Bolgrien,Nick G. Granin,and Leo Levin Abstract )o Satellite data are important in understanding the relation- Angoro R. ship between hydrodynamics and biological productivity in a Lcke Ecikol large )ake ecosystem. This was demonstrated using N2AA AvHRR,ond in silu temperature and chlorophyll fluorescence data to describe the seasonal temperature cycle and distribu- tion of algal biomass in Lake Baikal (Russia). Features such as ice cover, thermal fronts, and the dispersion of river water were describedin a seriesof imagesfrom 1990 and 1991. The northern basin retained ice cover until the end of Mav. In lune, thermal ftonts extending <t0 km from shore were obsewed to be associated with shallows, bays, and rivers. Offshore surface temperatures in the northern basin did not 7 exceed4"C until late lune-early JuIy. The southern and mid- O dle basinswarmed more quick)y than the northern bosin. In c phytoplankton l situ dofo showed concentrations to be low off- .P_ shore and high near thermal The Selenga River, the o Borguzin fronts. I largest tributary of Lake Baikal, supplied warm water and Bov nutrients which contributed to Localized increases in chloro- phyll fluorescence. Introduction Satellite data, in coniunction with field data, can be used to Lower SelengoR describethe seasonaltemperature cycle, thermal fronts, up- )l Angoro R. welling, and the dispersion of river water in large lakes (Mortimer,19BB; Lathrop et aL.,1990;Bolgrien and Brooks, t99Z). These featuresare important becausethey represent mechanismsby which heat, nutrients, and pollutants are dis- tributed. The horizontal and vertical distributions of plank- 108' ton are also highly dependenton thermal features.Because it is not feasibleto synoptically sample large lakes using ships, Figure1. -

Weathering Signals in Lake Baikal and Its Tributaries

Weathering signals in Lake Baikal and its tributaries Tim Jesper Suhrhoff1, Jörg Rickli1, Marcus Christl2, Elena G. Vologina3, Eugene V. Sklyarov3, and Derek Vance1 1Institute of Geochemistry and Petrology, ETH Zurich, Zurich, Switzerland ([email protected]) 2Laboratory of Ion Beam Physics, ETH Zurich, Zurich, Switzerland 3Institute of the Earth's Crust, Siberian Branch of the RAS, Irkutsk, Russia Silicate weathering and the long-term carbon cycle Figure 1: Illustration of the long-term carbon cycle and involved carbon fluxes (Berner, Figure 2: Schematic showing removal of atmospheric CO2 through silicate 1999). weathering (Ruddiman, 2008). The long-term carbon cycle refers to carbon fluxes between surface earth reservoirs and the lithosphere. Over long time scales (> several 100 kyrs), small imbalances in these fluxes can result in substantial changes of atmospheric CO2 concentrations. One of the processes removing CO2 from the atmosphere is the weathering of silicate rocks. We are interested in the relationship between climate and silicate weathering now and in the past, particularly in the context of past climate changes. EGU2020 presentation Suhrhoff et al. | 29.03.2019 | 2 Lake Baikal as a promising site to study variation of silicate rock weathering in both space and time: § Size and age: 20% of global freshwater, 30-40 Ma old § Periodic glaciations § Long, continuous sediment cores (dating back as much as 12 Ma) § Geology of the catchment is dominated by granitoid rocks (Colman, 1998; Karabanov et al., 1998; Williams et al., 2001; Karabanov et al., 2004; Zakharova et al., 2005 ; Sherstyankin et al., 2006; Fagel et al., 2007; Troitskaya et al., 2015; Panizzo et al., 2017) Figure 3: The location of Lake Baikal (Tulokhonov et al., 2015). -

BAIKAL RIFT BASEMENT: STRUCTURE and TECTONIC EVOLUTION RIFT DU Baikal: STRUCTURE ET EVOLUTION TECTONIQUE DU SOCLE

BAIKAL RIFT BASEMENT: STRUCTURE AND TECTONIC EVOLUTION RIFT DU BAiKAL: STRUCTURE ET EVOLUTION TECTONIQUE DU SOCLE Alexandre I. MELNIKOV, Anatoli M. MAZUKABZOV, Eugene V. SKLYAROV and Eugene P. VASILJEV MELNIKOV, A.I., MAZUKABZOV, A.M., SKLYAROV, EV & VASILJEV, E.P. (1994) ~ Baikal rift basement: structure and tectonic evolution. [Rift du Baikal: structure et evolution tectonique du socle]. - Bull. Centres Rech. Explor.-Prod. Elf Aquitaine, 18, 1, 99-122, 12 fig., 2 tab.; Boussens, June 30, 1994 - ISSN: 0396-2687. CODEN: BCREDP. Le systerne rift du Baikal, en Siberie orientale, possede une structure tres hete roqene en raison de l'anciennete de son histoire qui commence au Precarnbnen inferieur et se poursuit jusqu'au Cenozoique. On distingue deux traits structuraux majeurs: Ie craton siberian et Ie systerne oroqenlque Sayan-Ba'ikal, partie inteqrante de la ceinture oroqenique d'Asie centrale. Le craton siberian est forme par les unites suivantes: les terrains metamorphiques du Precarnbrien mterieur, la couverture sedimentaire vendienne-paleozorque sur laquelle les bassins paleozolques et mezosoiques sont surirnposes et une marge reactivee (suture) constituant la tran sition entre Ie craton et la ceinture oroqenique. Le systerne oroqenique Sayan-Baikal est forme par I'assemblage des terranes Barguzin, Tuva-Mongol et Dzhida. Les terranes du Barguzin et Tuva-Mongol sont composites; elle com portent des massifs du Precambrten inferieur, des terranes volcano-sedimentaires et carbonatees du Phanerozotque avec des granites intrusifs; ce sont donc des super-terranes. Les unites les plus anciennes sont des ophiolites datees a environ 1,1 a 1,3 Ga. dans la terrane Barguzin et 0,9 a 1,1 Ga dans celie de Tuva-Mongol. -

Climate History and Early Peopling of Siberia

22 Climate History and Early Peopling of Siberia Jiří Chlachula Laboratory for Palaeoecology, Tomas Bata University in Zlín, Czech Republic 1. Introduction Siberia is an extensive territory of 13.1 mil km2 encompassing the northern part of Asia east of the Ural Mountains to the Pacific coast. The geographic diversity with vegetation zonality including the southern steppes and semi-deserts, vast boreal taiga forests and the northern Arctic tundra illustrates the variety of the present as well as past environments, with the most extreme seasonal temperature deviations in the World ranging from +45ºC to -80ºC. The major physiographical units – the continental basins of the Western Siberian Lowland, the Lena and Kolyma Basin; the southern depressions (the Kuznetsk, Minusinsk, Irkutsk and Transbaikal Basin); the Central Siberian Plateau; the mountain ranges in the South (Altai, Sayan, Baikal and Yablonovyy Range) and in the NE (Stavonoy, Verkhoyanskyy, Suntar-Hajata, Cherskego, Kolymskyy Range) constitute the relief of Siberia. The World- major rivers (the Ob, Yenisei, Lena, Kolyma River) drain the territory into the Arctic Ocean. Siberia has major significance for understanding the evolutionary processes of past climates and climate change in the boreal and (circum-)polar regions of the Northern Hemisphere. Particularly the central continental areas in the transitional sub-Arctic zone between the northern Siberian lowlands south of the Arctic Ocean and the southern Siberian mountain system north of the Gobi Desert characterized by a strongly continental climate regime have have been in the focus of most intensive multidisciplinary Quaternary (palaeoclimate, environmental and geoarchaeological) investigations during the last decades. Siberia is also the principal area for trans-continental correlations of climate proxy records across Eurasia following the East-West and South-North geographic transects (Fig. -

Changing Nutrient Cycling in Lake Baikal, the World's Oldest Lake

Changing nutrient cycling in Lake Baikal, the world’s oldest lake George E. A. Swanna,1, Virginia N. Panizzoa,1, Sebastiano Piccolroazb, Vanessa Pashleyc, Matthew S. A. Horstwoodc, Sarah Robertsd, Elena Vologinae, Natalia Piotrowskaf, Michael Sturmg, Andre Zhdanovh, Nikolay Graninh, Charlotte Normana, Suzanne McGowana, and Anson W. Mackayi aSchool of Geography, University of Nottingham, Nottingham NG7 2RD, United Kingdom; bPhysics of Aquatic Systems Laboratory, School of Architecture, Civil and Environmental Engineering, Ecole Polytechnique Fédérale de Lausanne, CH-1015 Lausanne, Switzerland; cGeochronology and Tracers Facility, British Geological Survey, Nottingham NG12 5GG, United Kingdom; dCanada Centre for Inland Waters, Environment and Climate Change Canada, Burlington, ON L7S 1A1, Canada; eInstitute of Earth’s Crust, Siberian Branch, Russian Academy of Sciences, 664033 Irkutsk, Russia; fDivision of Geochronology and Environmental Isotopes, Institute of Physics–Centre for Science and Education, Silesian University of Technology, 44-100 Gliwice, Poland; gEidgenössische Anstalt für Wasserversorgung, Abwasserreinigung und Gewässerschutz–Eidgenössische Technische Hochschule, Swiss Federal Institute of Aquatic Science and Technology, 8600 Dübendorf, Switzerland; hLimnology Institute, Siberian Branch, Russian Academy of Sciences, 6644033 Irkutsk, Russia; and iEnvironmental Change Research Centre, Department of Geography, University College London, London WC1E 6BT, United Kingdom Edited by John P. Smol, Queen’s University, Kingston, ON, Canada, and accepted by Editorial Board Member David W. Schindler September 14, 2020 (received for review June 24, 2020) Lake Baikal, lying in a rift zone in southeastern Siberia, is the world’s communities have undergone rapid multidecadal to multicentennial oldest, deepest, and most voluminous lake that began to form over timescale changes over the last 2,000 y (16). -

BH Baikal GIS JOPL 2008

Published in: Journal of Paleolimnology (2008), vol. 39, iss.4, pp. 567-584 Status: Postprint (Author’s version) Assembly and concept of a web-based GIS within the paleolimnological project CONTINENT (Lake Baikal, Russia) 1Birgit Heim · 2Jens Klump · 1Hedi Oberhänsli · 3Nathalie Fagel 1Climate Dynamics and Sediments, GeoForschungsZentrum Potsdam, 14473 Potsdam, Germany 2Data Centre, GeoForschungsZentrum Potsdam, 14473 Potsdam, Germany 3Geology Department, Clays and Paleoclimate, University of Liège, 4000 Liege, Belgium Abstract Web-based Geographical Information Systems (GIS) are excellent tools within interdisciplinary and multi- national geoscience projects to exchange and visualize project data. The web-based GIS presented in this paper was designed for the paleolimnological project 'High-resolution CONTI-NENTal paleoclimate record in Lake Baikal' (CONTINENT) (Lake Baikal, Siberia, Russia) to allow the interactive handling of spatial data. The GIS database combines project data (core positions, sample positions, thematic maps) with auxiliary spatial data sets that were downloaded from freely available data sources on the world wide web. The reliability of the external data was evaluated and suitable new spatial datasets were processed according to the scientific questions of the project. GIS analysis of the data was used to assist studies on sediment provenance in Lake Baikal, or to help answer questions such as whether the visualization of present-day vegetation distribution and pollen distribution supports the conclusions derived from palynological analyses. The refined geodata are returned back to the scientific community by using online data publication portals. Data were made citeable by assigning persistent identifiers (DOI) and were published through the German National Library for Science and Technology (TIB Hannover, Hannover, Germany).