Identity Orchestration and the Language of Hip-Hop Narratives

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

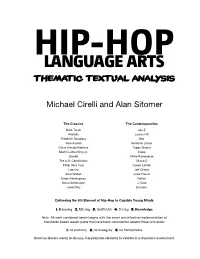

Language Arts Thematic Textual Analysis

HIP-HOPLANGUAGE ARTS THEMATIC TEXTUAL ANALYSIS Michael Cirelli and Alan Sitomer The Classics The Contemporaries Mark Twain Jay-Z Aristotle Lauryn Hill Frederick Douglass Nas Jane Austen Kendrick Lamar Oliver Wendell Holmes Tupac Shakur Martin Luther King Jr. Drake Gandhi Afrika Bambaataa The U.S. Constitution Chuck D Philip Vera Cruz Queen Latifah Lao-tzu Jeff Chang Alice Walker Lupe Fiasco Ernest Hemingway Rakim Sonia Sotomayor J. Cole Junot Díaz Eminem Delivering the 5th Element of Hip-Hop to Capable Young Minds 1. B-boying 2. MC-ing 3. Graffiti Art 4. DJ-ing 5. Knowledge Note: All work contained herein begins with the smart and effective implementation of standards-based lesson plans that have been constructed around three principles: 1. no profanity 2. no misogyny 3. no homophobia Great vocabulary words to discuss; inappropriate elements to validate in a classroom environment. HipHopLanguageArts3.indd 1 06/03/2015 15:38:37 2 | READ CLOSELY HIP-HOP INTERPRETATION GUIDE Question: Is violence ever an appropriate solution for resolving conflict? Consider the following text: from “Murder to Excellence” by Kanye West (with Jay-Z) I’m from the murder capital, where they murder for capital Heard about at least 3 killings this afternoon Lookin’ at the news like dang I was just with him after school, No shop class but half the school got a tool, And I could die any day type attitude Plus his little brother got shot reppin’ his avenue It’s time for us to stop and re-define black power 41 souls murdered in 50 hours 1. -

In Defense of Rap Music: Not Just Beats, Rhymes, Sex, and Violence

In Defense of Rap Music: Not Just Beats, Rhymes, Sex, and Violence THESIS Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Master of Arts Degree in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Crystal Joesell Radford, BA Graduate Program in Education The Ohio State University 2011 Thesis Committee: Professor Beverly Gordon, Advisor Professor Adrienne Dixson Copyrighted by Crystal Joesell Radford 2011 Abstract This study critically analyzes rap through an interdisciplinary framework. The study explains rap‟s socio-cultural history and it examines the multi-generational, classed, racialized, and gendered identities in rap. Rap music grew out of hip-hop culture, which has – in part – earned it a garnering of criticism of being too “violent,” “sexist,” and “noisy.” This criticism became especially pronounced with the emergence of the rap subgenre dubbed “gangsta rap” in the 1990s, which is particularly known for its sexist and violent content. Rap music, which captures the spirit of hip-hop culture, evolved in American inner cities in the early 1970s in the South Bronx at the wake of the Civil Rights, Black Nationalist, and Women‟s Liberation movements during a new technological revolution. During the 1970s and 80s, a series of sociopolitical conscious raps were launched, as young people of color found a cathartic means of expression by which to describe the conditions of the inner-city – a space largely constructed by those in power. Rap thrived under poverty, police repression, social policy, class, and gender relations (Baker, 1993; Boyd, 1997; Keyes, 2000, 2002; Perkins, 1996; Potter, 1995; Rose, 1994, 2008; Watkins, 1998). -

Runway Shows and Fashion Films As a Means of Communicating the Design Concept

RUNWAY SHOWS AND FASHION FILMS AS A MEANS OF COMMUNICATING THE DESIGN CONCEPT A thesis submitted to the College of the Arts of Kent State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts By Xiaohan Lin July 2016 2 Thesis written by Xiaohan Lin B.S, Kent State University, 2014 M.A., Kent State University, 2016 Approved by ______________________________________________ Name, Thesis Supervisor ______________________________________________ Name, Thesis Supervisor or Committee Member ______________________________________________ Name, Committee Member ______________________________________________ Dr. Catherine Amoroso Leslie, Graduate Studies Coordinator, The Fashion School ______________________________________________ Dr. Linda Hoeptner Poling, Graduate Studies Coordinator, The School of Art ______________________________________________ Mr. J.R. Campbell, Director, The Fashion School ______________________________________________ Dr. Christine Havice, Director, The School of Art ______________________________________________ Dr. John Crawford-Spinelli, Dean, College of the Arts 3 REPORT OF THESIS FINAL EXAMINATION DATE OF EXAM________________________ Student Number_________________________________ Name of Candidate_______________________________________ Local Address_______________________________________ Degree for which examination is given_______________________________________ Department or School (and area of concentration, if any)_________________________ Exact title of Thesis_______________________________________ -

Rose, T. Prophets of Rage: Rap Music & the Politics of Black Cultural

Information Services & Systems Digital Course Packs Rose, T. Prophets of Rage: Rap Music & the Politics of Black Cultural Expression. In: T.Rose, Black noise : rap music and black culture in contemporary America. Hanover, University Press of New England, 1994, pp. 99-145. 7AAYCC23 - Youth Subcultures Copyright notice This Digital Copy and any digital or printed copy supplied to or made by you under the terms of this Staff and students of King's College London are Licence are for use in connection with this Course of reminded that copyright subsists in this extract and the Study. You may retain such copies after the end of the work from which it was taken. This Digital Copy has course, but strictly for your own personal use. All copies been made under the terms of a CLA licence which (including electronic copies) shall include this Copyright allows you to: Notice and shall be destroyed and/or deleted if and when required by King's College London. access and download a copy print out a copy Except as provided for by copyright law, no further copying, storage or distribution (including by e-mail) is Please note that this material is for use permitted without the consent of the copyright holder. ONLY by students registered on the course of study as stated in the section above. All The author (which term includes artists and other visual other staff and students are only entitled to creators) has moral rights in the work and neither staff browse the material and should not nor students may cause, or permit, the distortion, mutilation or other modification of the work, or any download and/or print out a copy. -

Lightning in a Bottle

LIGHTNING IN A BOTTLE A Sony Pictures Classics Release 106 minutes EAST COAST: WEST COAST: EXHIBITOR CONTACTS: FALCO INK BLOCK-KORENBROT SONY PICTURES CLASSICS STEVE BEEMAN LEE GINSBERG CARMELO PIRRONE 850 SEVENTH AVENUE, 8271 MELROSE AVENUE, ANGELA GRESHAM SUITE 1005 SUITE 200 550 MADISON AVENUE, NEW YORK, NY 10024 LOS ANGELES, CA 90046 8TH FLOOR PHONE: (212) 445-7100 PHONE: (323) 655-0593 NEW YORK, NY 10022 FAX: (212) 445-0623 FAX: (323) 655-7302 PHONE: (212) 833-8833 FAX: (212) 833-8844 Visit the Sony Pictures Classics Internet site at: http:/www.sonyclassics.com 1 Volkswagen of America presents A Vulcan Production in Association with Cappa Productions & Jigsaw Productions Director of Photography – Lisa Rinzler Edited by – Bob Eisenhardt and Keith Salmon Musical Director – Steve Jordan Co-Producer - Richard Hutton Executive Producer - Martin Scorsese Executive Producers - Paul G. Allen and Jody Patton Producer- Jack Gulick Producer - Margaret Bodde Produced by Alex Gibney Directed by Antoine Fuqua Old or new, mainstream or underground, music is in our veins. Always has been, always will be. Whether it was a VW Bug on its way to Woodstock or a VW Bus road-tripping to one of the very first blues festivals. So here's to that spirit of nostalgia, and the soul of the blues. We're proud to sponsor of LIGHTNING IN A BOTTLE. Stay tuned. Drivers Wanted. A Presentation of Vulcan Productions The Blues Music Foundation Dolby Digital Columbia Records Legacy Recordings Soundtrack album available on Columbia Records/Legacy Recordings/Sony Music Soundtrax Copyright © 2004 Blues Music Foundation, All Rights Reserved. -

The Life & Rhymes of Jay-Z, an Historical Biography

ABSTRACT Title of Dissertation: THE LIFE & RHYMES OF JAY-Z, AN HISTORICAL BIOGRAPHY: 1969-2004 Omékongo Dibinga, Doctor of Philosophy, 2015 Dissertation directed by: Dr. Barbara Finkelstein, Professor Emerita, University of Maryland College of Education. Department of Teaching and Learning, Policy and Leadership. The purpose of this dissertation is to explore the life and ideas of Jay-Z. It is an effort to illuminate the ways in which he managed the vicissitudes of life as they were inscribed in the political, economic cultural, social contexts and message systems of the worlds which he inhabited: the social ideas of class struggle, the fact of black youth disempowerment, educational disenfranchisement, entrepreneurial possibility, and the struggle of families to buffer their children from the horrors of life on the streets. Jay-Z was born into a society in flux in 1969. By the time Jay-Z reached his 20s, he saw the art form he came to love at the age of 9—hip hop— become a vehicle for upward mobility and the acquisition of great wealth through the sale of multiplatinum albums, massive record deal signings, and the omnipresence of hip-hop culture on radio and television. In short, Jay-Z lived at a time where, if he could survive his turbulent environment, he could take advantage of new terrains of possibility. This dissertation seeks to shed light on the life and development of Jay-Z during a time of great challenge and change in America and beyond. THE LIFE & RHYMES OF JAY-Z, AN HISTORICAL BIOGRAPHY: 1969-2004 An historical biography: 1969-2004 by Omékongo Dibinga Dissertation submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of the University of Maryland, College Park, in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy 2015 Advisory Committee: Professor Barbara Finkelstein, Chair Professor Steve Klees Professor Robert Croninger Professor Derrick Alridge Professor Hoda Mahmoudi © Copyright by Omékongo Dibinga 2015 Acknowledgments I would first like to thank God for making life possible and bringing me to this point in my life. -

“Rapper's Delight”

1 “Rapper’s Delight” From Genre-less to New Genre I was approached in ’77. A gentleman walked up to me and said, “We can put what you’re doing on a record.” I would have to admit that I was blind. I didn’t think that somebody else would want to hear a record re-recorded onto another record with talking on it. I didn’t think it would reach the masses like that. I didn’t see it. I knew of all the crews that had any sort of juice and power, or that was drawing crowds. So here it is two years later and I hear, “To the hip-hop, to the bang to the boogie,” and it’s not Bam, Herc, Breakout, AJ. Who is this?1 DJ Grandmaster Flash I did not think it was conceivable that there would be such thing as a hip-hop record. I could not see it. I’m like, record? Fuck, how you gon’ put hip-hop onto a record? ’Cause it was a whole gig, you know? How you gon’ put three hours on a record? Bam! They made “Rapper’s Delight.” And the ironic twist is not how long that record was, but how short it was. I’m thinking, “Man, they cut that shit down to fifteen minutes?” It was a miracle.2 MC Chuck D [“Rapper’s Delight”] is a disco record with rapping on it. So we could do that. We were trying to make a buck.3 Richard Taninbaum (percussion) As early as May of 1979, Billboard magazine noted the growing popularity of “rapping DJs” performing live for clubgoers at New York City’s black discos.4 But it was not until September of the same year that the trend gar- nered widespread attention, with the release of the Sugarhill Gang’s “Rapper’s Delight,” a fifteen-minute track powered by humorous party rhymes and a relentlessly funky bass line that took the country by storm and introduced a national audience to rap. -

Central Saint Martins Fashion Fund

central saint martins fashion fund Fashion at Central Saint Martins (CSM) is internationally and critically acclaimed. The CSM Fashion Fund will provide programme- wide support for our students, equipment and facilities. The funds raised will contribute to the provision of the world-class education we are renowned for. As a thank-you for this support, we will invite donors to exclusive events and record their generosity in a visible area of the fashion studios. Richard Quinn, MA 2016 fashion inspiration St Martin’s School of Art was established in The internationally renowned centre for arts and design education has one of the most 1859. The first fashion course, headed by Muriel established reputations in fashion education Pemberton, started in 1932 and by the 1970s, and is considered a global leader in its field. St Martin’s School of Art was established, as one The Business of Fashion of the pre-eminent colleges for the study of The many individual careers and artistic contributions that were formed in the fashion. In 1989 St Martin’s joined the Central fashion department of Central Saint Martins School of Art and Design to become Central are well documented. Beyond those, though, Saint Martins College of Art and Design, bringing are a set of standards and a sense of cultural ambition that can’t be attributed to any one Fashion, Textiles and Jewellery Design together designer or teacher. And that’s what’s at the in the School of Fashion and Textile Design. In heart of its success and continuing relevance. It’s almost like an ideology. -

A Hip-Hop Copying Paradigm for All of Us

Pace University DigitalCommons@Pace Pace Law Faculty Publications School of Law 2011 No Bitin’ Allowed: A Hip-Hop Copying Paradigm for All of Us Horace E. Anderson Jr. Elisabeth Haub School of Law at Pace University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.pace.edu/lawfaculty Part of the Entertainment, Arts, and Sports Law Commons, and the Intellectual Property Law Commons Recommended Citation Horace E. Anderson, Jr., No Bitin’ Allowed: A Hip-Hop Copying Paradigm for All of Us, 20 Tex. Intell. Prop. L.J. 115 (2011), http://digitalcommons.pace.edu/lawfaculty/818/. This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the School of Law at DigitalCommons@Pace. It has been accepted for inclusion in Pace Law Faculty Publications by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@Pace. For more information, please contact [email protected]. No Bitin' Allowed: A Hip-Hop Copying Paradigm for All of Us Horace E. Anderson, Jr: I. History and Purpose of Copyright Act's Regulation of Copying ..................................................................................... 119 II. Impact of Technology ................................................................... 126 A. The Act of Copying and Attitudes Toward Copying ........... 126 B. Suggestions from the Literature for Bridging the Gap ......... 127 III. Potential Influence of Norms-Based Approaches to Regulation of Copying ................................................................. 129 IV. The Hip-Hop Imitation Paradigm ............................................... -

Hip-Hop Timeline 1973 – Kool Herc Deejays His First Party in the Bronx

Hip-hop Timeline ➢ 1973 – Kool Herc deejays his first party in the Bronx, where his blending of breaks is first exhibited. The break dancers in attendance began to discover their style and form. ➢ 1975 – Grandmaster Flash begins the early forms of Turntabilism by blending and mixing, while Grandwizard Theodore invents what we now know as scratching. The first Emcee crews are formed. ➢ 1979 – The Sugarhill Gang, under the guidance of record label owner and former vocalist Sylvia Robinson, release Rapper’s Delight, the first commercially recognized rap song. *There is much debate over the first recorded rap song, but it’s widely believed to have been done sometime in 1977 or 1978. ➢ 1980 – Kurtis Blow releases the first best selling hip-hop album, The Breaks, and becomes the first star in hip-hop music. ➢ 1983 – Herbie Hancock, in collaboration with pioneer DeeJay GrandMixer DST (now known as GrandMixer DXT), creates the Grammy Award-winning song Rockit, which is the first time the public ever hears a DeeJay scratching on record. Pioneer hip-hop duo Run DMC releases their first single Sucker Emcee’s. ➢ 1988 – This year is considered the first golden year in hip-hop music with releases such as Public Enemy’s It Takes A Nation of Millions to Hold Us Back, Big Daddy Kane’s Long Live The Kane, Slick Rick’s The Great Adventures of Slick Rick, Boogie Down Production’s By All Means Necessary, Eric B And Rakim’s Follow the Leader and the first highly regarded non-New York hip-hop record, N.W.A.’s Straight Outta Compton. -

“Raising Hell”—Run-DMC (1986) Added to the National Registry: 2017 Essay by Bill Adler (Guest Post)*

“Raising Hell”—Run-DMC (1986) Added to the National Registry: 2017 Essay by Bill Adler (guest post)* Album cover Label Run-DMC Released in May of 1986, “Raising Hell” is to Run-DMC what “Sgt. Pepper’s” is to the Beatles--the pinnacle of their recorded achievements. The trio--Run, DMC, and Jam Master Jay--had entered the album arena just two years earlier with an eponymous effort that was likewise earth-shakingly Beatlesque. Just as “Meet the Beatles” had introduced a new group, a new sound, a new language, a new look, and a new attitude all at once, so “Run-DMC” divided the history of hip-hop into Before-Run-DMC and After-Run-DMC. Of course, the only pressure on Run-DMC at the very beginning was self-imposed. They were the young guns then, nothing to lose and the world to gain. By the time of “Raising Hell,” they were monarchs, having anointed themselves the Kings of Rock in the title of their second album. And no one was more keenly aware of the challenge facing them in ’86 than the guys themselves. Just a year earlier, LL Cool J, another rapper from Queens, younger than his role models, had released his debut album to great acclaim. Run couldn’t help but notice. “All I saw on TV and all I heard on the radio was LL Cool J,” he recalls, “Oh my god! It was like I was Richard Pryor and he was Eddie Murphy!” Happily, the crew was girded for battle. Run-DMC’s first two albums had succeeded as albums, not just a collection of singles--a plan put into effect by Larry Smith, who produced those recordings with Russell Simmons, the group’s manager. -

Published Sheet Music from the Rudy Vallee Collection

Published Sheet Music from the Rudy Vallee Collection The Rudy Vallee collection contains almost 30.000 pieces of sheet music (about two thirds published and the rest manuscripts); about half of the titles are accessible through a database and we are presenting here the first ca. 2000 with full information. Song: 21 Guns for Susie (Boom! Boom! Boom!) Year: 1934 Composer: Myers, Richard Lyricist: Silverman, Al; Leslie, Bob; Leslie, Ken Arranger: Mason, Jack Song: 33rd Division March Year: 1928 Composer: Mader, Carl Song: About a Quarter to Nine From: Go into Your Dance (movie) Year: 1935 Composer: Warren, Harry Lyricist: Dubin, Al Arranger: Weirick, Paul Song: Ace of Clubs, The Year: 1926 Composer: Fiorito, Ted Arranger: Huffer, Fred Song: Ace of Diamonds, The Year: 1926 Composer: Fiorito, Ted Arranger: Huffer, Fred Song: Ace of Spades, The Year: 1926 Composer: Fiorito, Ted Arranger: Huffer, Fred K. Song: Actions (speak louder than words) Year: 1931 Composer: Vallee, Rudy; Himber, Richard; Greenblatt, Ben Lyricist: Vallee, Rudy; Himber, Richard; Greenblatt, Ben Arranger: Prince, Graham Song: Adios Year: 1931 Composer: Madriguera, Enric Lyricist: Woods, Eddie; Madriguera, Enric(Spanish translation) Arranger: Raph, Teddy Song: Adorable From: Adorable (movie) Year: 1933 Composer: Whiting, Richard A. Lyricist: Marion, George, Jr. Arranger: Mason, Jack; Rochette, J. (vocal trio) Song: African Lament (Lamento Africano) Year: 1931 Composer: Lecuona, Ernesto Lyricist: Gilbert, L. Wolfe Arranger: Katzman, Louis Song: African Lament (Lamento Africano)