My Bengal Kamala Lecture January 10, 2013 It Is a Privilege to Be Asked to Give the Kamala Lecture. It Would Be, for Anyone

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Famous Indian Classical Musicians and Vocalists Free Static GK E-Book

oliveboard FREE eBooks FAMOUS INDIAN CLASSICAL MUSICIANS & VOCALISTS For All Banking and Government Exams Famous Indian Classical Musicians and Vocalists Free static GK e-book Current Affairs and General Awareness section is one of the most important and high scoring sections of any competitive exam like SBI PO, SSC-CGL, IBPS Clerk, IBPS SO, etc. Therefore, we regularly provide you with Free Static GK and Current Affairs related E-books for your preparation. In this section, questions related to Famous Indian Classical Musicians and Vocalists have been asked. Hence it becomes very important for all the candidates to be aware about all the Famous Indian Classical Musicians and Vocalists. In all the Bank and Government exams, every mark counts and even 1 mark can be the difference between success and failure. Therefore, to help you get these important marks we have created a Free E-book on Famous Indian Classical Musicians and Vocalists. The list of all the Famous Indian Classical Musicians and Vocalists is given in the following pages of this Free E-book on Famous Indian Classical Musicians and Vocalists. Sample Questions - Q. Ustad Allah Rakha played which of the following Musical Instrument? (a) Sitar (b) Sarod (c) Surbahar (d) Tabla Answer: Option D – Tabla Q. L. Subramaniam is famous for playing _________. (a) Saxophone (b) Violin (c) Mridangam (d) Flute Answer: Option B – Violin Famous Indian Classical Musicians and Vocalists Free static GK e-book Famous Indian Classical Musicians and Vocalists. Name Instrument Music Style Hindustani -

And Joydeep Ghosh (Sarod)

The Asian Indian Classical Music Society 51491 Norwich Drive Granger, IN 46530 Concert Announcement Vidushi Mita Nag (sitar) Pandit Joydeep Ghosh (sarod) with Pandit Subhen Chatterjee (Tabla) April 26, 2016, Tuesday, 7.00PM At: the Andrews Auditorium, Geddes Hall University of Notre Dame Cosponsored with the Liu Institute of Asia and Asian Studies Tickets available at gate. General Admission: $10, AICMS Members and ND/SMC faculty: $5, Students: FREE Mita Nag, daughter of the veteran sitarist, Pandit Manilal Nag and granddaughter of Sangeet Acharya Gokul Nag, belongs to the Vishnupur Gharana of Bengal, a school of music that is nearly 300 years old and which is known for its dhrupad style of playing. She was initiated into music at the age of four, and studied with her mother, grandfather and father. She appeared for her debut performance at the age of ten, when she also won the Government of India’s Junior National Talent Search Award. She has given many concert performances, both alone and with her father, in cities in the US, Canada, Japan and Europe as well as in India. Joydeep Ghosh is hailed as one of India’s leading sarod, surshringar and Mohanveena artists. He started his sarod training at the age of five, and has studied with the great masters the late Sangeetacharya Anil Roychoudhury , late Sangeetacharya Radhika Mohan Moitra and Padmabhusan Acharya Buddhadev Dasgupta all of the Shahajahanpur Gharana. He has won numerous awards and fellowships, including those from the Government of India, the title of “Suramani” from the Sur Singar Samsad (Mumbai) and “Swarshree” from Swarankur (Mumbai). -

Women in India's Freedom Struggle

WOMEN IN INDIA'S FREEDOM STRUGGLE When the history of India's figf^^M independence would be written, the sacrifices made by the women of India will occupy the foremost plofe. —^Mahatma Gandhi WOMEN IN INDIA'S FREEDOM STRUGGLE MANMOHAN KAUR IVISU LIBBARV STERLING PUBLISHERS PRIVATE LIMITED .>».A ^ STERLING PUBLISHERS PRIVATE LIMITED L-10, Green Park Extension, New Delhi-110016 Women in India's Freedom Strug^e ©1992, Manmohan Kaur First Edition: 1968 Second Edition: 1985 Third Edition: 1992 ISBN 81 207 1399 0 -4""D^/i- All rights are reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted, in any form or by any means, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without prior written permission of the publisher. PRINTED IN INDIA Published by S.K. Ghai, Managing Director, Sterling Publishers Pvt. Ltd., L-10, Green Park Extension, New Delhi-110016. Laserset at Vikas Compographics, A-1/2S6 Safdarjung Enclave, New Delhi-110029. Printed at Elegant Printers. New Delhi. PREFACE This subject was chosen with a view to recording the work done by women in various phases of the freedom struggle from 1857 to 1947. In the course of my study I found that women of India, when given an opportunity, did not lag behind in any field, whether political, administrative or educational. The book covers a period of ninety years. It begins with 1857 when the first attempt for freedom was made, and ends with 1947 when India attained independence. While selecting this topic I could not foresee the difficulties which subsequently had to be encountered in the way of collecting material. -

Teachers of Private Colleges (Under Section 17 – Elected Members (6) of the Kerala University Act, 1974)

1 Price Rs. 100/- per copy UNIVERSITY OF KERALA Election to the Senate from the Teachers of Private Colleges (Under Section 17 – Elected Members (6) of the Kerala University Act, 1974) ELECTORAL ROLL OF TEACHERS OF PRIVATE COLLEGES-2018 ROLL No. Name Designation College 1. Dr.Caroline Beena Mendez DDO All Saints’ College. 2. Sonya J Nair Assistant Professor ,, 3. Kukku Xavier Assistant Professor ,, 4. Dr.Liji Varghese Assistant Professor ,, 5. Dr.Sr.Pascoela Adelrich Assistant Professor ,, D’Souza 6. Dr.Rajsree M.S Assistant Professor ,, 7. Sapna Srinivas Assistant Professor ,, 8. Simna S Stephen Assistant Professor ,, 9. Nishel Prem Elias Assistant Professor ,, 10. Diana V Prakash Assistant Professor ,, 11. Dr.Kavitha .N Assistant Professor ,, 12. Joveeta Justin Assistant Professor ,, 13. Celina James Assistant Professor ,, 14. Dr.C.Udayakala Assistant Professor ,, 15. Parvathy Menon Assistant Professor ,, 16. Vijayakumari K Assistant Professor ,, 17. Dr.Sreelekha Nair Associate professor ,, 18. Dr.Reshmi.R.Prasad Associate professor ,, 19. Lissy Bennet Assistant Professor ,, 20. Shirly Joseph Associate professor All Saints’ College. 21. Sebina Mathew C Assistant Professor ,, 22. Renjini Raveendran P Assistant Professor ,, 23. Vidhya T.R Assistant Professor ,, 24. Dr.Deepa M Associate professor ,, 25. Dr.Anjana P.S Assistant Professor ,, 2 26. Dr.Veena Suresh Babu Assistant Professor ,, 27. Dr.Sunitha Kurur Assistant Professor ,, 28. Dr.Sindhu Yesodharan Assistant Professor ,, 29. Dr.Siji V.L Assistant Professor ,, 30. Dr.Beena Kumari K.S Assistant Professor ,, 31. Dr.Nisha K.K Assistant Professor ,, 32. Dr.Sr.Shaina T J Assistant Professor ,, 33. Dr.Dhanalekshmi.T.G Assistant Professor ,, 34. Divya Grace Dilip Assistant Professor ,, 35. -

Acrs-GDMO-NFSG

ACR Monitoring Sub Cadre: GDMO-NFSG(Regular) S.No. Name of the Officer DOB Emp.No.Grade Name of the Institution Years for which where working 2002-03 2003-04 2004-05 2005-06 2006-07 2007-08 2008-09 2009-10 2010-11 2011-122012-13 2013-14 ACR awaited 1 Dr. Dal Chand 1.8.54 472 NFSG SJH Yes* Yes No No No No Vol. ret.w.e.f. 30.10.2004 2 Dr. V.Lakshmi Rajyam 6.11.48 548 NFSG CGHS, Hyderabad yes yes No Yes Yes Yes 3 Dr. V.Saraswathy 1.7.48 661 NFSG CGHS, Mumbai Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes No 4 Dr. Usha Sapra 8.7.48 663 NFSG CGHS, Delhi yes yes C Yes Yes Yes 5 Dr. Gurjeet SinghSoin 19.12.48 664 NFSG NCT, Delhi yes yes incom Yes No No 6 Dr. D.N.Das 1.1.48 746 NFSG CGHS, Guwahati 7 Dr. M.M. Poddar 23.9.50 4049 NFSG RLTRI, Raipur Yes Yes Yes* Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes *1.4.04 to 15.10.04 reqd. 8 Dr. (S) Santosh Jain 10.12.47 4115 NFSG P&T Rajasthan yes yes Yes Yes Yes No 9 Dr. G.D. Phukan 4.11.48 727 NFSG P&T Guwahati Yes No No No Yes No 10 Dr. Gandharv Pradhan 9.2.49 737 NFSG NCT, Delhi No No No No No No 11 Dr. B.P.Vithal Kumar 27.02.51 741 NFSG RLTRI, Gouripur yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes 12 Dr S.K. -

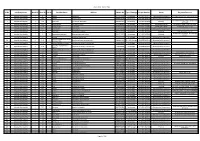

Sl No Localbody Name Ward No Door No Sub No Resident Name Address Mobile No Type of Damage Unique Number Status Rejection Remarks

Flood 2019 - Vythiri Taluk Sl No Localbody Name Ward No Door No Sub No Resident Name Address Mobile No Type of Damage Unique Number Status Rejection Remarks 1 Kalpetta Municipality 1 0 kamala neduelam 8157916492 No damage 31219021600235 Approved(Disbursement) RATION CARD DETAILS NOT AVAILABLE 2 Kalpetta Municipality 1 135 sabitha strange nivas 8086336019 No damage 31219021600240 Disbursed to Government 3 Kalpetta Municipality 1 138 manjusha sukrutham nedunilam 7902821756 No damage 31219021600076 Pending THE ADHAR CARD UPDATED ANOTHER ACCOUNT 4 Kalpetta Municipality 1 144 devi krishnan kottachira colony 9526684873 No damage 31219021600129 Verified(LRC Office) NO BRANCH NAME AND IFSC CODE 5 Kalpetta Municipality 1 149 janakiyamma kozhatatta 9495478641 >75% Damage 31219021600080 Verified(LRC Office) PASSBOOK IS NO CLEAR 6 Kalpetta Municipality 1 151 anandavalli kozhathatta 9656336368 No damage 31219021600061 Disbursed to Government 7 Kalpetta Municipality 1 16 chandran nedunilam st colony 9747347814 No damage 31219021600190 Withheld PASSBOOK NOT CLEAR 8 Kalpetta Municipality 1 16 3 sangeetha pradeepan rajasree gives nedunelam 9656256950 No damage 31219021600090 Withheld No damage type details and damage photos 9 Kalpetta Municipality 1 161 shylaja sasneham nedunilam 9349625411 No damage 31219021600074 Disbursed to Government Manjusha padikkandi house 10 Kalpetta Municipality 1 172 3 maniyancode padikkandi house maniyancode 9656467963 16 - 29% Damage 31219021600072 Disbursed to Government 11 Kalpetta Municipality 1 175 vinod madakkunnu colony -

1563121524GENERAL CLASS ROLL.Pdf

College FormNo CandidateName DOB Father Mother ElectiveSubject Roll AG/001 601 JAYA ROY 06-10-2000 LATE JAYANTA ROY CHANDANA ROY Political Science,Bengali,Education AG/002 602 URMILA SARKAR 17-09-1999 SUKUMAR SARKAR REBA SARKAR Political Science,Education,History AG/003 603 BASANTI MAHATO 05-03-1997 SUBODH MAHATO GOURI MAHATO Political Science,Education,History AG/004 604 TAPAN MANDAL 31-07-1998 BIREN MANDAL DEBI MANDAL Political Science,Bengali,History AG/005 605 KARTIK HEMBROM 11-02-2002 GONESH HEMBROM SABINA BESHRA Political Science,Education,History AG/006 606 TANIA ROY 15-01-2001 PARIMAL ROY SHILPI ROY Political Science,Education,History AG/007 607 SHIKHA MANDAL 04-05-2000 JADAB MANDAL SAGARI MANDAL Political Science,Bengali,Education AG/008 608 JYOTI ROY 06-10-2000 LATE JAYANTA ROY CHANDANA ROY Political Science,Bengali,Education AG/009 609 ASHIS OJHA 16-05-1997 MANGAL OJHA KANAKLATA OJHA Political Science,Education,History AG/0010 610 SUPARNA BISWAS 10-05-2001 SUNIL KUMAR BISWAS RATNA BISWAS Political Science,Bengali,History AG/0012 611 SATHI PAL 08-11-2001 TARUN PAL CHHABI PAL Political Science,Education,History AG/0013 612 NABANITA BISWAS 17-11-2001 BINOY KUMAR BISWAS ANITA BISWAS Political Science,Education,History AG/0015 613 URMILA BALA 08-02-2002 MANGAL BALA RAMALA BALA Political Science,Bengali,History AG/0016 614 ALO MONDAL 12-02-2001 DILIP MONDAL MANJU RANI MONDAL Political Science,Education,History AG/0017 615 TOSLIMA NASRIN 25-05-2002 BABLU SK TOHONINA BIBI Political Science,Bengali,Education AG/0019 616 RINKU BISWAS -

(Public Section) Padma Awards Directory (1954-2009) Year-Wise List Sl

MINISTRY OF HOME AFFAIRS (Public Section) Padma Awards Directory (1954-2009) Year-Wise List Sl. Prefix First Name Last Name Award State Field Remarks 1954 1 Dr. Sarvapalli Radhakrishnan BR TN Public Affairs Expired 2 Shri Chakravarti Rajagopalachari BR TN Public Affairs Expired 3 Dr. Chandrasekhara Raman BR TN Science & Eng. Expired Venkata 4 Shri Nand Lal Bose PV WB Art Expired 5 Dr. Satyendra Nath Bose PV WB Litt. & Edu. 6 Dr. Zakir Hussain PV AP Public Affairs Expired 7 Shri B.G. Kher PV MAH Public Affairs Expired 8 Shri V.K. Krishna Menon PV KER Public Affairs Expired 9 Shri Jigme Dorji Wangchuk PV BHU Public Affairs 10 Dr. Homi Jehangir Bhabha PB MAH Science & Eng. Expired 11 Dr. Shanti Swarup Bhatnagar PB UP Science & Eng. Expired 12 Shri Mahadeva Iyer Ganapati PB OR Civil Service 13 Dr. J.C. Ghosh PB WB Science & Eng. Expired 14 Shri Maithilisharan Gupta PB UP Litt. & Edu. Expired 15 Shri Radha Krishan Gupta PB DEL Civil Service Expired 16 Shri R.R. Handa PB PUN Civil Service Expired 17 Shri Amar Nath Jha PB UP Litt. & Edu. Expired 18 Shri Malihabadi Josh PB DEL Litt. & Edu. 19 Dr. Ajudhia Nath Khosla PB DEL Science & Eng. Expired 20 Shri K.S. Krishnan PB TN Science & Eng. Expired 21 Shri Moulana Hussain Madni PB PUN Litt. & Edu. Ahmed 22 Shri V.L. Mehta PB GUJ Public Affairs Expired 23 Shri Vallathol Narayana Menon PB KER Litt. & Edu. Expired Wednesday, July 22, 2009 Page 1 of 133 Sl. Prefix First Name Last Name Award State Field Remarks 24 Dr. -

Journal of Bengali Studies

ISSN 2277-9426 Journal of Bengali Studies Vol. 6 No. 1 The Age of Bhadralok: Bengal's Long Twentieth Century Dolpurnima 16 Phalgun 1424 1 March 2018 1 | Journal of Bengali Studies (ISSN 2277-9426) Vol. 6 No. 1 Journal of Bengali Studies (ISSN 2277-9426), Vol. 6 No. 1 Published on the Occasion of Dolpurnima, 16 Phalgun 1424 The Theme of this issue is The Age of Bhadralok: Bengal's Long Twentieth Century 2 | Journal of Bengali Studies (ISSN 2277-9426) Vol. 6 No. 1 ISSN 2277-9426 Journal of Bengali Studies Volume 6 Number 1 Dolpurnima 16 Phalgun 1424 1 March 2018 Spring Issue The Age of Bhadralok: Bengal's Long Twentieth Century Editorial Board: Tamal Dasgupta (Editor-in-Chief) Amit Shankar Saha (Editor) Mousumi Biswas Dasgupta (Editor) Sayantan Thakur (Editor) 3 | Journal of Bengali Studies (ISSN 2277-9426) Vol. 6 No. 1 Copyrights © Individual Contributors, while the Journal of Bengali Studies holds the publishing right for re-publishing the contents of the journal in future in any format, as per our terms and conditions and submission guidelines. Editorial©Tamal Dasgupta. Cover design©Tamal Dasgupta. Further, Journal of Bengali Studies is an open access, free for all e-journal and we promise to go by an Open Access Policy for readers, students, researchers and organizations as long as it remains for non-commercial purpose. However, any act of reproduction or redistribution (in any format) of this journal, or any part thereof, for commercial purpose and/or paid subscription must accompany prior written permission from the Editor, Journal of Bengali Studies. -

Indian Political Thaught Unit Iii

INDIAN POLITICAL THAUGHT UNIT III Paper Code – 18MPO22C Class – I M.A POLITICAL SCIENCE Faculty Name – M.Deepa Contact No. 9489345565 RAJA RAM MOHAN ROY LIFE AND TIME OF RAJA RAM MOHAN ROY ✓ He was born in 1772, in Radhanagar village in Murshidabad District of West Bengal. ✓ Bengal, after 1765, came under British East India company, Colonial rule, centred in Kolkata, was expanding in all parts of India. Limited constitutional reforms, capitalist economy, English education, etc were being introduced. ✓ Studied Arbic & Persian in Patna, Sanskrit in Banaras, English later on a company official, Besides Bengali and Sanskrit, Roy had mastered Arabic, Persian, Hebrew, Greek, Latin and many other leading language. ✓ Besides Hinduism, he learnt Islam, Buddhism, and Christianity. Through this he developed belief in unity of God, and Religion. INFLUENCE ✓ John Locke, Bentham , David Hume, ✓ 1830 he went to England with many purposes-one was requesting more pension to Mughal King Akkbar-II Who gave him the title of Raja. He died there on 1833. HIS RELIGIOUS THOUGHT ✓ Influenced by Enlightenment spirit and Utilitarian Liberalism. ✓ Human have God gifted sense of reason and intellect to assess the trust and social utility in religious doctrine, no need for any intermediary-priest, Pandit UNITY IN ALL RELIGION ✓ Universal Supreme being, Existence of soul, Life after death ✓ But, all religion suffer from dogmas, ritualism, irrational beliefs & Practices; to benefit the intermediaries and keep people in dark ✓ Hinduism suffered from polytheism, idolatry, superstitions, ritualism. ✓ Ancient purity of Hindu religion-as contained in Veda & Upanishad-lost in faulty interpretation, orthodoxy, conservatism in the wake of tyrannical and despotic Muslim and Rajput Rules. -

November 2013

MOTHER INDIA MONTHLY REVIEW OF CULTURE SPECIAL ISSUE 24 NOVEMBER 2013 PRICE: Rs. 30.00 SUBSCRIPTIONS INLAND Annual: Rs. 200.00 For 10 years: Rs. 1,800.00 Price per Single Copy: Rs. 30.00 OVERSEAS Sea Mail: Annual: $35 or Rs. 1,400.00 For 10 years: $350 or Rs. 14,000.00 Air Mail: Annual: $70 or Rs. 2,800.00 For 10 years: $700 or Rs. 28,000.00 All payments to be made in favour of Mother India, Sri Aurobindo Ashram, Pondicherry. For outstation cheques kindly add Rs. 15 for annual membership and Rs. 50 for 10-year subscription. Subscribers are requested to mention their subscription number in case of any enquiry. The correspondents should give their full address in BLOCK letters, with pin code. Lord, Thou hast willed, and I execute, A new light breaks upon the earth, A new world is born. The things that were promised are fulfilled. All Rights Reserved. No matter appearing in this journal or part thereof may be reproduced or translated without written permission from the publishers except for short extracts as quotations. The views expressed by the authors are not necessarily those of the journal. All correspondence to be addressed to: MOTHER INDIA, Sri Aurobindo Ashram, Pondicherry - 605 002, India Phone: (0413) 2233642 e-mail: [email protected] Publishers: Sri Aurobindo Ashram Trust Founding Editor: K. D. SETHNA (AMAL KIRAN) Editors: RAVI, HEMANT KAPOOR, RANGANATH RAGHAVAN Published by: MANOJ DAS GUPTA SRI AUROBINDO ASHRAM TRUST PUBLICATION DEPARTMENT, PONDICHERRY 605 002 Printed by: SWADHIN CHATTERJEE at Sri Aurobindo Ashram Press, Pondicherry 605 002 PRINTED IN INDIA Registered with the Registrar of Newspapers under No. -

A Hermeneutic Study of Bengali Modernism

Modern Intellectual History http://journals.cambridge.org/MIH Additional services for Modern Intellectual History: Email alerts: Click here Subscriptions: Click here Commercial reprints: Click here Terms of use : Click here FROM IMPERIAL TO INTERNATIONAL HORIZONS: A HERMENEUTIC STUDY OF BENGALI MODERNISM KRIS MANJAPRA Modern Intellectual History / Volume 8 / Issue 02 / August 2011, pp 327 359 DOI: 10.1017/S1479244311000217, Published online: 28 July 2011 Link to this article: http://journals.cambridge.org/abstract_S1479244311000217 How to cite this article: KRIS MANJAPRA (2011). FROM IMPERIAL TO INTERNATIONAL HORIZONS: A HERMENEUTIC STUDY OF BENGALI MODERNISM. Modern Intellectual History, 8, pp 327359 doi:10.1017/S1479244311000217 Request Permissions : Click here Downloaded from http://journals.cambridge.org/MIH, IP address: 130.64.2.235 on 25 Oct 2012 Modern Intellectual History, 8, 2 (2011), pp. 327–359 C Cambridge University Press 2011 doi:10.1017/S1479244311000217 from imperial to international horizons: a hermeneutic study of bengali modernism∗ kris manjapra Department of History, Tufts University Email: [email protected] This essay provides a close study of the international horizons of Kallol, a Bengali literary journal, published in post-World War I Calcutta. It uncovers a historical pattern of Bengali intellectual life that marked the period from the 1870stothe1920s, whereby an imperial imagination was transformed into an international one, as a generation of intellectuals born between 1885 and 1905 reinvented the political category of “youth”. Hermeneutics, as a philosophically informed study of how meaning is created through conversation, and grounded in this essay in the thought of Hans Georg Gadamer, helps to reveal this pattern.