Freedom to Reacl Foundation News

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Index of /Sites/Default/Al Direct/2012/July

AL Direct, July 5, 2012 Contents American Libraries Online | ALA News | Booklist Online Anaheim Update | Division News | Awards & Grants | Libraries in the News Issues | Tech Talk | E-Content | Books & Reading | Tips & Ideas Great Libraries of the World | Digital Library of the Week | Calendar The e-newsletter of the American Library Association | July 5, 2012 American Libraries Online Copyright for librarians and teachers, in a nutshell Carrie Russell writes: “You may have wondered whether you hold the copyright to work you’ve put many hours into creating on the job. Who holds the copyright to works created by teachers or librarians? Short answer: In general, when employees create works as a condition of employment, the copyright holder is the employer.”... American Libraries feature Library giant Russell Shank dies Russell Shank (right), 86, professor emeritus at the University of California, Los Angeles’s Graduate School of Education and Information Studies, 1977–1988 university librarian at UCLA, and a renowned leader who made his mark in academic, special, and public librarianship as well as in intellectual freedom and international librarianship, died June 26 of complications from a fall at his home. At Annual Conference in Anaheim, Shank (who was ALA President in 1978–1979) was among the library leaders acknowledged at the June 21 Library Champions and Past Presidents Reception.... AL: Inside Scoop, July 2 Information Toronto library hosts a comics festival Literacy: Beyond Robin Brenner writes: “The Toronto Comic Arts Library 2.0 asks and Festival may not have the name recognition of answers the big multimedia geek extravaganzas like San Diego Comic- questions facing those Con International, but to devoted attendees, TCAF who teach information has become the must-attend comics event of the literacy: Where have year. -

Online Finding

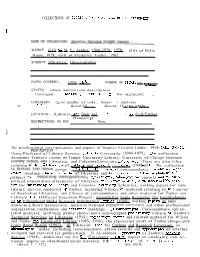

COLLECTIONS OF CORfillSPONDENCE hKD ~~NUSCRIPT DOCill1ENTS ') SOURCE: Gift of M. F., Tauber, 1966-1976; 1978; Gift of Ellis Mount, 1979; Gift of Frederick Tauber, 1982 SUBJECT: libraries; librarianship DATES COVERED: 1935- 19.Q2:;...·_· NUMBER OF 1TEHS; ca. 74,300- t - .•. ,..- STATUS: (check anoroor La te description) Cataloged: Listed:~ Arranged:-ll- Not organized; _ CONDITION: (give number of vols., boxes> or shelves) vc Bound:,...... Boxed:231 Stro r ed; 11 tape reels LOCATION:- (Library) Rare Book and CALL~NtJHBER Ms Coll/Tauber Manuscript RESTRICTIONS ON USE None --.,.--....---------------.... ,.... - . ) The professional correspondence and papers of Maurice Falcolm Tauber, 1908- 198~ Melvil!. DESCRIPTION: Dewey Professor' of Library Service, C9lumbia University (1944-1975). The collection documents Tauber's career at Temple University Library, University of Chicago Graduate LibrarySghooland Libraries, and ColumbiaUniver.sity Libra.:t"ies. There are also files relating to his.. ~ditorship of College' and Research Libraries (1948...62 ). The collection is,d.ivided.;intot:b.ree series. SERIESL1) G'eneral correspondence; inchronological or4er, ,dealing with all aspects of libraries and librarianship•. 2)' Analphabet1cal" .subject fi.~e coni;ainingcorrespQndence, typescripts, .. mJnieographed 'reports .an~,.::;~lated printed materialon.allaspects of libraries and. librarianship, ,'lith numerou§''':r5lders for the University 'ofCh1cago and Columbia University Libraries; working papers for many library surveys conducted by Tauber, including 6 boxes of material relating to his survey of Australian libraries; and 2 boxes of correspondence and other material for Tauber and Lilley's ,V.S. Officeof Education Project: Feasibility Study Regarding the Establishment of an Educational Media Research Information Service (1960); working papers of' many American Library Association, American National Standards~J;:nstituteand other professional organization conferences and committee meetings. -

5/1/113 Conference Arrangements Office Annual Conferences Tapes 1952, 1956-57, 1960-61, 1963, 1965, 1967, 1970-72, 1975-93, 1995, 1997-2004

5/1/113 Conference Arrangements Office Annual Conferences Tapes 1952, 1956-57, 1960-61, 1963, 1965, 1967, 1970-72, 1975-93, 1995, 1997-2004 Box 1: 1952 Annual Conference, 71st, New York. 5 reels "Internal public relations for librarians," T.J. Ross "The small public library program" "The public library and the political process," Carma R. Zimmerman "Librarians bridge the world," Norman Cousins "Books are basic for better international relations," Eleanor Roosevelt 1956 Annual Conference, 75th, Miami Beach, FL. 1 reel "Interviews with librarians, American and foreign, attending the 1956 conference" 1957 Annual Conference, 76th, Kansas City, MO. 1 reel "General Session, 2nd and speech by Harry Truman" 1960 Joint Conference, American Library Association and Canadian Library Association, Montreal. 2 reels 1961 Annual Conference, 80th, Cleveland, OH. 2 reels "General Session, first" "General Session, second" 1963 Annual Conference, 82nd, Chicago. 4 reels "Recordings of various speeches" 1965 Annual Conference, 84th, Detroit. 1 reel "Current trends in public administration," Sidney Mailick 1967 Annual Conference, 86th, San Francisco. 1 reel Part I: Public Relations Section "The sights and sounds of libraries panel" Part II: Young Adult Services Division "Way-out ways of teaching the young adult" 1970 Annual Conference, 89th, Detroit. 1 reel "Margaret Walker speech" 1970 Annual Conference, 89th, Detroit. 2 reels "Project INTREX," Charles H. Stevens 1971 Annual Conference, 90th, Dallas. 1 reel "Audiovisual committee meeting, June 23, John Grierson, speaker 1975 Annual Conference, 94th, San Francisco. 4 reels "General Session I" "General Session II" "General Session III, Libraries and the development and future of tax support" "General Session IV, Inaugural Luncheon" 1976 Annual Conference, 95th, Chicago. -

76Th Annual Conference Proceedings of the American Library Association

AMERICAN LIBRARY ASSOCIATION 76th Annual Conference Proceedings of the American Library Association At Kansas City, Missouri June 23-29, 1957 AMERICAi\; LIBRARY ASSOCIATION 50 EAST HURON STREET CHICAGO 11. ILLINOIS A M E R I C A N L I B R A R Y A S S O C I A T JI O N 76th Annual Conference Proceedings of the American Library Association l{ansas City, Missouri June 23-29, 1957 • AMERICAN LIBRARY ASSOCIATION 50 EAST HURON STREET CHICAGO 11, ILLINOIS 1957 ALA Conference Proceedings Kansas City, Missouri GENERAL SESSIONS First General Session. I Second General Session. 2 Third General Session. 3 Membership Meeting . 5 COUNCIL SESSIONS ALA Council . 7 PRE-CONFERENCE INSTITUTES Adult Education Institute ......................................................... 10 "Opportunities Unlimited" ....................................................... 11 TYPE-OF-LIBRARY DIVISIONS American Association of School Librarians .......................................... 12 Association of College and Research Libraries ........................................ 16 Committee on Foundation Grants .............................................. 17 Junior College Libraries Section .............................................. 17 Libraries of Teacher-Training Institutions Section ............................... 18 Pure and Applied Science Section. 18 Committee on Rare Books, Manuscripts and Special Collections .................. 19 University Libraries Section...... 19 Association of Hospital and Institution Libraries ...................................... 20 Public -

College and Research Libraries

A CRL Board of Directors Midwinter Meeting 1963 BRIEF OF MINUTES of the nominees appears elsewhere in this January 30 issue. Present: President Katharine M. Stokes; On a motion by Jay Lucker the board Vice President and President-elect Neal R. voted to approve a petition to organize a Harlow; Past President Ralph E. Ellsworth; Slavic and East European Subsection in the directors-at-large, Jack E. Brown, Andrew J. Subject Specialists Section. It was voted to Eaton, Flora Belle Ludington, Lucile M. approve the Bylaws of the Junior College Morsch; directors on ALA Council, Helen Lib~aries Section, following a motion by M. Brown, Dorothy M. Drake, James Hum Lucile Morsch. On motions by Mr. Harlow phry, III, Russell Shank, Mrs. Margaret K. and Miss Ludington the board voted to Spangler; chairmen of Sections, Charles M. terminate the Burma Projects Committee Adams, H. Richard Archer, Virginia Clark, and the Library 21 Committee, respectively. David Kaser, Jay K. Lucker, Reta E. King Discussion of matters involved in imple (representing Felix E. Hirsch); vice chairmen menting the report of the Special Committee of Sections, Dale M. Bentz, Wrayton E. Gard on ACRL Program led the group to consider ner, Eli M. Oboler; past chairmen of Sec at some length the entire question of re tions, Helen Wahoski, James 0. Wallace, cruiting members for ALA and its divisions Irene Zimmerman; ACRL Executive Secre and sections. It was the sense of the meeting tary Joseph H. Reason. Committee chair that the best job of recruiting is done by in men present were Lorena A. -

Download This PDF File

News from the Field ACQUISITIONS copies of nine poems and two novels, and thirty-five articles in magazine form; letters THE LIBRARY OF UCLA on February 20 from London to friends, and the original acquired a copy of the first printed edition drawing for the frontispiece of "Son of the of the complete works of Plato-0 pera Wolf." Omnia, 1513-its two-millionth book. Tlie UNIVERSITY OF HAWAII'S Hilo campus gift was from members of the faculty, alum has received a collection of one thousand ni association, Regents, and Friends of the volumes in the fields of drama, the theater, Library. The two-million-and-first volume, avant-garde verse, and nineteenth-century arriving the morning of the presentation American fiction from James I. Hubler. ceremonies for the Aldine Plato, was a ninth-century Arabian astrological work, Al Carl G. Stroven, university librarian at bumazar's De Magnis Coniiunctionibus, Rat the University of Hawaii in Honolulu has dolt, 1489, the gift of the University of presented eight hundred volumes to the Hilo California library in Berkeley and of its campus library to form a basic collection librarian, Donald Coney. of English and American literature. UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA, San Diego, UNIVERSITY OF KENTUCKY library has re has acquired the ten-thousand volume li ceived a large part of the library of the late brary of Americo Castro, Hispanic scholar Dr. Emmett F. Horine including his ·collec who is professor-in-residence of Spanish lit tion on Daniel Drake and his times, and erature at UCSD. materials on the history of medicine and STANFORD UNIVERSITY libraries in early medical schools in Kentucky, and medical February received the eighty-drawer index bibliography. -

Special Libraries, January 1961

San Jose State University SJSU ScholarWorks Special Libraries, 1961 Special Libraries, 1960s 1-1-1961 Special Libraries, January 1961 Special Libraries Association Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.sjsu.edu/sla_sl_1961 Part of the Cataloging and Metadata Commons, Collection Development and Management Commons, Information Literacy Commons, and the Scholarly Communication Commons Recommended Citation Special Libraries Association, "Special Libraries, January 1961" (1961). Special Libraries, 1961. 1. https://scholarworks.sjsu.edu/sla_sl_1961/1 This Magazine is brought to you for free and open access by the Special Libraries, 1960s at SJSU ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Special Libraries, 1961 by an authorized administrator of SJSU ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. SPECIAL LIBRARIES ASSOCIATION Putting Knoudedge to lVork OFFICERS DIRECTORS President SARAALILI. WINIFREDSEWELL University of I-lous!on Squibb Institute for Medical Research Housfon 4, Texm New Brunswirk, New Jersey LORRAINECIBOCH First Vice-president and President-Elect Charles Bruniug Co., Inr. EUGENEB. JACKSON Mount Prospect, Illinois General Motors Corpor~!ron,l~urrci:. ,Ilirbi.p.m Second Vice-president W. ROY HOLLEMAN PAUL L. KNAPP Scripps Institution of Oceanography The Ohio Oil Com.,b.my. Li~tlrtoo,Colorado La Jolla, California Secretary ALVINAF. WASSENBERG MRS. JEANNE B. NORTH Kaiser Aluminum b Chemical Corp. United Aircrajr Corporation, Elst Ifartford 8, C'onn. Spokane, Washington Treasurer MRS. ELIZABETHR. USHER OLIVEE. KENNEDY Metropolitan Museum of Art Room S600, 30 Rockejelicr Plax, Seu~I'ork, N. 1'. hTew YorR, New York Immediate Past-President DONALDWASSON DR. BURTONW. ADKINSON Council on Foreign Relations National Science Foundation, Washington, D. C. New York, New York EXECUTIVE SECRETARY: BILL M. -

Americ.N Libraries from a Eropean Angle, and the National Commission on Fir

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 082 790 LI 004 512 TITLE Coping with Change: The Challenge for Research Libraries. Minutes of the Meeting (82nd, May 11-12, 1973, New Orleans, Louisiana). INSTITUTION Association of Research Libraries, Washington, D.C. PUB DATE May 73 NOTE 121p.(0 references) AVAILABLF FROM The Association of Research Libraries, 1527 New Hampshire Ave., N.W., Washington, D. C. 20036 ($5.00) EDRS PRICE MF-$0.65 HC-$6.58 DESCRIPTORS Change Agents; Conference Reports; Financial Support; *Library Associations; *Library Automation; *Management; Meetings; Post Secondary Education; *Research Libraries; University Libraries IDENTIFIERS *Association of Research Libraries; National Commission on Libraries and Information ABSTRACT The program elements of this meeting focus ,on what research libraries are doing in response to opportunities -to meet challenges of changing educational trends, the threats of shifting financial basest and improved techniques in management and operation. The Lollowing presentations were made under the general heading "Changing Technology: Machine-Readable Data Bases": Introduction, Computer - readable data bases: library processing and use, Libraries, Librarians and Computerized Data Bases, The Northeast Academic Science Information Center, Future Possibilities for Large-Scale Data Base Use, and Information for Contemporary Times. Other presentations were made on: the National Commission on Libraries and Information Science, the Management Review and Analysis Program, the Role and Objectives or the Association of Research Libraries (ARL) as a Agent for Ch.Lnge, the Changing Role of the University Library Director, Americ.n Libraries from a Eropean Angle, and the National Commission on Fir. ncing Postsecondary Education. These program presentations are folloc d by the business meeting and committee reports. -

Special Libraries, September 1967

San Jose State University SJSU ScholarWorks Special Libraries, 1967 Special Libraries, 1960s 9-1-1967 Special Libraries, September 1967 Special Libraries Association Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.sjsu.edu/sla_sl_1967 Part of the Cataloging and Metadata Commons, Collection Development and Management Commons, Information Literacy Commons, and the Scholarly Communication Commons Recommended Citation Special Libraries Association, "Special Libraries, September 1967" (1967). Special Libraries, 1967. 7. https://scholarworks.sjsu.edu/sla_sl_1967/7 This Magazine is brought to you for free and open access by the Special Libraries, 1960s at SJSU ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Special Libraries, 1967 by an authorized administrator of SJSU ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. R,special libraries I Slptemher 1967, uoL. 58, no. 7 1967 Convention and Annu~~lReports Indispensable - the 160 articles, 28 7 illustrations, 456 pages in SUPPLEMENTARY VOLUME 2 of the ENCYCLOPAEDIC DICTIONARY OF PHYSICS To maintain the authority, recency and comprehensive coverage of this major reference work, annual Supple- mentary Volumes are issued which reflect new develop- ments and changing emphases in many branches of physics. Subiects not previously covered in the main volumes, and newer aspects of already treated material, are presented in these Supplements. The 9 volume ENCYCLOPAEDIC DICTIONARY OF Library Journal soid "This work is the most signifi- PHYSICS has been called ". o serious and monu- con1 contribution to the reference literature of physics mental endeavor . a very useful addition lo Ihe since 1923, when Glozebrook's Dictionary of Applied 'first aid' kit of any library in colleges, schools, and Physics appeared. -

Special Libraries, March 1968

San Jose State University SJSU ScholarWorks Special Libraries, 1968 Special Libraries, 1960s 3-1-1968 Special Libraries, March 1968 Special Libraries Association Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.sjsu.edu/sla_sl_1968 Part of the Cataloging and Metadata Commons, Collection Development and Management Commons, Information Literacy Commons, and the Scholarly Communication Commons Recommended Citation Special Libraries Association, "Special Libraries, March 1968" (1968). Special Libraries, 1968. 3. https://scholarworks.sjsu.edu/sla_sl_1968/3 This Magazine is brought to you for free and open access by the Special Libraries, 1960s at SJSU ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Special Libraries, 1968 by an authorized administrator of SJSU ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. PROGRESS IN NUCLEAR MAGNETIC RESONANCE SPECTROSCOPY, Volume 3 Edited by J. W. Emsley, Durham University; J. Feeney, Varian Associates, Ltd.; and L. Sutcliffe, Liverpool University, all England 420 pages, 161 illustrations $18.00 THE PAPER-MAKING MACHINE: Its Invention, Evolution and Development By R. H. Clapperton, British Paper and Board Makers Association, England 366 pages, 175 illustrations $32.00 BlOGENESlS OF NATURAL COMPOUNDS, Second Edition, revised and enlarged Edited by Peter Bernfeld, Bio-Research Institute, Cambridge, Massachusetts 1,204 pages, 598 illustrations $44.00 COLLlSlONAL ACTIVATION IN GASES INTERNATIONAL ENCYCLOPEDIA OF PHYSICAL CHEMISTRY AND CHEMICAL PHYSICS, TOPIC 19: GAS KINETICS, VOLUME 3 By Brian Stevens, Sheffield University, England 248 pages, 52 illustrations $14.00 UREA AS A PROTEIN SUPPLEMENT Edited by Michael H. Briggs, Analytical 1-aboratories Ltd., England 480 pages, 42 illustrations $18.00 ENTOMOLOGICAL PARASITOLOGY FOUNDATIONS OF EUCLIDEAN The Relations Between Entomology AND NON-EUCLIDEAN and the Medical Sciences GEOMETRIES ACCORDING TO INTERNATIONAL SERIES OF F. -

IDEALS @ Illinois

ILLINOIS UNIVERSITY OF ILLINOIS AT URBANA-CHAMPAIGN PRODUCTION NOTE University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign Library Large-scale Digitization Project, 2007. LIBRARY TRENDS FALL 1989 38(2)1.53-325 Problem Solving in Libraries A Festschrift in Honor of Herbert Goldhor Ronald R. Powell Issue Editor University of Illinois Graduate School of Library and Information Science LIBRARY TRENDS FALL 1989 38(2)153-325 Problem Solving in Libraries A Festschrift in Honor of Herbert Goldhor Ronald R. Powell Issue Editor University of Illinois Graduate School of Library and Information Science STATEMENT OF OWNERSHIP, MANAGEMENT AND CIRCULATION 1. Titlr of publiration: Library Trends. 2. Date of filing. 1 Drcrmbrr 1989. 3. Frrqucncy of1ssue:quarterly: no of issues puhlishtd annually: four;annual subscription price. $50 (plus $3 foroverseas suhwribers) 1.1.ocation of known office of publication: Klnivrrsit) of Illinois Graduate School of Lihrar) and Iniormation Science, 249 Armory Bldg , 505 E. Armory St., Champaign. IL 61820 6. Puhlirher Univcrsitv of Illinois Graduate School of Lihrar) and Information Sciencr, Champaign, 1L 61820, Editor.F W. lanraster, 410 David Kinley Hall, 1407W. Gregory Dr., Urbana, IL61801; Managing Editor: James S. Dowling, 249 Armory Bldg., 505F. Armory St., Champaign. 1L61820. 7. Owner. L'nivcrsity of Illinois Graduate School of Library and Information Srwnrr, 249 Armory Bldg.. 50.5 E. Armory St, Champaign, IL 61820. 8. Known hondholdcrs, mortgagres, and othrr security holdrrs owning or holding 1 percent or more of total amount of bonds, mort%dges or other securities: None. 9. The purpose, function, and nonprofit status of the organization and the rxrmpt sratus for Federal inrome tax purposes have not c hanged during preceding 12 months. -

Library Resources & Technical Services

LIBRARY RESOURCES& TECHNICAL SERVICES tr1o|.tq, No. z Spring t97o CONTENTS Page Acquisitions in 1969,.Ashby l. Fristoe and Rose E. Myers r65 The Year's Work in Cataloging-ry6g. Richard O. Pautzsch r74 Developments in Reproduction of Library Materials, 1969. Robert C. Sulliuan r89 A Serials Synopsis: rgfig. Mary Pound 23r The Processing Department of the Library of Congress in 1969. William J. Welsh n6 Foreign Blanket Orders: Precedent and Practice. Robert Wedgeworth 258 State Libraries and Centralized Processing.F. William Summers 269 Report of the Photocopying Costs in Libraries Committee. Robert C. Sulliuan 279 Regional Groups Report. Marian Sanner 290 IFLA International Meeting of Cataloguing Experts, Copenhagen, 1969.A. H. Chaplin 292 ERIC/CLIS Abstracts 30r Reviews 306 ALA RESOURCES AND TECHNICAL SERVICES DIVISION EDITOITIAL BOAI{D Editor, and Chairmanof the Editorial Board . .. Peur,S. DuNxtx Assistant Editors: Asrrcv J. Fnrs'ror C. Dorlern Coox for Cataloging antl ClassificatiotlScc(ioll Menv Pouru ...... for SelialsSection Roennr C. SurrrveN for Reproduction of Library l\{aterials Section Editorial Aduisors: Marrrice F. Tauber (for Technical Sen'ices) Marian Sanner (for Regional Groups) Managing Editor . .. DoulyN J. Hrcxrv Library Resources & Technical Seruices,the quarterly official publication of the Resourcesand Technical ServicesDivision of the American Library Association,is pub- lished at zgor Byrdhill Road, Richmond, Va. zgzo5.Ed,itorial Office:Graduate School of Library Service, Rutgers-The State University, New Brunswick, N. J. o8go3. Adaertising, Circulation, and. Business Offi.ce:Central Production Unit, Journals, ALA Headquarters,5oE. Huron St., Chicago,Ill.6o6rr. SubscriptionPrice: to membersof the ALA Resourcesand Technical ServicesDivision, $r.25 per year, included in the membetship dues; to nonmembers,$5.oo per year, single copies$r.25, orders of five or more copies (sameissue or assorted),$r.oo each.