Sports and Competition Law: an Overview of EU and National Case Law

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

No Transmission of Critical Voices

February 2020 Media Progamme South East Europe No Transmission of Critical Voices Hendrik Sittig, Darija Fabijanić In Serbia there is currently an economic crime thriller happening on the television market and this before the parliament elections on the 26th April. The story is about several cable providers and the media group „United Media“ (parent enterprise: „United Group“) with its TV channel N1 that belongs to the media companies in Serbia which report critically about the government. The state-owned cable provider “Pošta Net“ has already removed the channels of United Media from its programme last December because they couldn’t agree on a contract renewal. As a result, many households couldn’t receive N1 anymore. Since Mid-January more viewers are affected, as the cable provider under the state „Telekom Serbia“ hasn’t prolonged their contracts either. A public exchange with accusations of political and economic interference between the players followed. Similar situations in the neighbouring countries can be observed. But let’s be clear from the get-go: The situation is more complicated than that and political reasons are not the only explanation for it. Serbia: Commercial conflict or political influence before the elections? The public dispute between the two telecommunication companies Telekom Serbia and United Group which has its own cable providers and the media company “United Media”, has been dominating the headlines in Serbia for several days now. The cable providers of the brand “Supernova” which belong to Telekom didn’t prolong the contract for transmitting the “United Media” channels. Therefore, since January about 200 000 households can’t watch 17 channels. -

Client-Facing Slide Templates

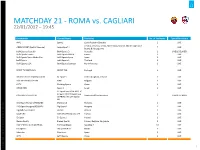

MATCHDAY 21 - ROMA vs. CAGLIARI 22/01/2017 – 19:45 Broadcaster Channel Name Territories No. of Territories Type of Broadcast AMC Sport1 Czech Republic/Slovakia 2 LIVE Croatia, Slovenia, Serbia, Macedonia, Kosovo, Montenegro and ARENA SPORT (Serbia Telecom) Arena Sport 4 7 LIVE Bosnia & Herzegovina beIN Sports Australia BeIN Sports 3 Australia 1 LIVE & DELAYED BeIN Sports France beIN Sports MAX 6 France 1 LIVE BeIN Sports Spain Media Pro beIN Sports Spain Spain 1 LIVE beIN Sports beIN Sports 1 Thailand 1 LIVE BeIN Sports USA BeIN Sports Connect North America 2 LIVE SPORT TV PORTUGAL SPORT.TV3 Portugal 1 LIVE BRITISH TELECOMMUNICATION BT Sport 3 United Kingdom, Ireland 2 LIVE BTV MEDIA GROUP EAD RING Bulgaria 1 LIVE CCTV Molding Sports China 1 LIVE CHARLTON Sport 2 Israel 1 LIVE TC Sport Live 04 DE HD / TC Linear 3 HD / TC Sport Live CINETRADE/TELECLUB Switzerland/Liechtenstein 2 LIVE & DELAYED 03 FR HD / TC 174 Sports HD DIGI Sport Hungary/RCS&RDS DigiSport 2 Romania 1 LIVE DIGI Sport Hungary/RCS&RDS DigiSport 1 Hungary 1 LIVE DigitAlb/SuperSport SS2HD Albania 1 LIVE DIGITURK beIN SPORTS HD 4 & OTT Turkey 1 LIVE Eir Sport Eir Sport 1 Ireland 1 LIVE Eleven Sports Eleven Sports Poland, Belgium, Singapore 3 LIVE FOX SPORTS LATIN AMERICA ESPN Caribbean See Slide 4 54 LIVE GO Sports GO Sports HD1 Malta 1 LIVE Movistar Movistar+ Spain 1 LIVE LETV LeTV Sports China 1 LIVE 2 Copyright ©2016 The Nielsen Company. Confidential proprietary. Nielsen and Confidential The Company. Copyright ©2016 MATCHDAY 21 - ROMA vs. -

2021 IIHF Ice Hockey World Championship, Latvia Broadcast Partners List

2021 IIHF Ice Hockey World Championship, Latvia Broadcast Partners List 18.05.2021 / Subject to change RIGHTS PROVISION Region Licensed Territory/ies Broadcaster TV TV RADIO NEWS MOBILE INTERNET BROADBAND HIGHLIGHTS Africa Comoros, Mauritius, Mayotte, Réunion, Seychelles L'Equipe X Asia China CCTV X X Chinese Taipei Elta X X X X X Korea Republic SBS Korea X Macau TDM Macau X Singapore Singtel X Caribbean Anguilla, Antigua & Barbuda, Aruba, Barbados, Bonaire, British Virgin Islands, Cayman Islands, Curaçao, Dominica, Grenada, Guadelupe, Haiti, Jamaica, Martinique, Montserrat, Saba, Saint Kitts and Nevis, Saint Lucia, Saint Vincent and the Grenadines, St. Barth, St. Eustatius, Trinidad and Tobago, Turks and Caicos Islands DIRECTV X Bermuda, Cayman Islands, Puerto Rico, US Virgin Islands NHL Network X X X X X ESPN+ X Dominican Republic, Guadelupe, Haiti, Martinique, St. Barth, St. Martin, Trinidad and Tobago L'Equipe X Europe Andorra L'Equipe X Austria ORF TV X X X Belarus BTRC X Bosnia and Herzegovina Arena Sport X X X X X X Croatia Arena Sport X X X X X X Czech Republic Czech Radio X X Czech TV X Hokej.cz X Denmark TV2 Denmark X X X X X Estonia ERR X X X X X Finland MTV Finland X X X X France L'Equipe X Georgia Silknet X Germany Sport 1 Germany X X X X X ARD TV X X RTL/N-TV X X Hungary AMC Sport 1 Hungary X Ireland Premier Sports X X Israel Sport 1 Israel X X X X X X Italy DAZN X Kazakhstan QAZsport X Kosovo Arena Sport X X X X X X Latvia Lattelecom X X X X X LTV Latvia X Latvian Radio X X Liechtenstein SRG SSR_RSI X X SRG SSR_RTS X X SRG -

Záujem O Ďuriša

Piatok 25 rokov tipovania na Slovensku nike.sk 16. 12. 2016 NAJLEPŠIE KURZY – SUPERŠANCA 1 X 2 70. ročník • číslo 291 41131 SLOVENSKO – BIELORUSKO 2,00 4,55 3,05 16:15 cena 0,60 40300 RUSKO – ČESKO 1,42 6,45 5,70 17:00 40301 TPS TURKU – SPORT VAASA 1,77 4,30 4,25 17:30 40302 JYVÄSKYLÄ – ÄSSÄT PORI 1,93 4,10 3,75 17:30 40168 UNION BERLÍN – FÜRTH 1,83 3,65 4,65 18:30 41133 NORIMBERG – STRAUBING 1,63 5,05 4,35 19:30 41132 ŠVAJČIARSKO – FRANCÚZSKO 1,50 5,40 5,15 20:15 40167 HOFFENHEIM – DORTMUND 4,45 4,15 1,83 20:30 App Store pre iPad a iPhone / Google Play pre Android 40174 HAMILTON – GLASGOW RANGERS 5,85 4,20 1,62 20:45 Za každým gólom Strana 7 je tvrdá drina S MARIÁNOM HOSSOM nielen o hokeji, Strany 8 a 9 ale aj o veľkom hrnci manželkinej skvelej kapustnice Dnes s Bieloruskom Vladimír Dravecký bol v štyroch zápasoch ka- pitán slovenskej hokejovej reprezentácie a ním vedený tím štyrikrát vyhral. Bude táto úspešná séria pokračovať aj na Švajčiarskom Strana 3 pohári v Bieli, do ktorého vstúpia naši dnešným zápasom s Bieloruskom? FOTO TASR/MICHAL SVÍTOK Záujem o Ďuriša Legia Varšava síce hľadá náhradu za odchádzajúceho Nemanju Nikoliča, ale slovenský útočník Viktorie Plzeň Michal Ďuriš ňou s najväčšou pravdepodobnosťou nebude. Ak napriek platnej zmluve odíde zo šatne úradujúceho českého majstra, tak inam. Záujemcov je viacero... FOTO TASR/MICHAL SVÍTOK Náš vodný pólista Ďalšie číslo humoristického Lukáš Seman nastúpi v Belehrade za výber sveta časopisu BUMerang Strana 21 POZOR! UŽ ZAJTRA 2 NÁZORY piatok 16. -

Minút Bez Gólu

Štvrtok 20. 4. 2017 71. ročník • číslo 91 cena 0,60 App Store pre iPad a iPhone / Google Play pre Android MARTIN KOHÚT, prezident Slovenského zväzu ľadového hokeja: Strany 8 a 9 Budúcnosťou sú Šatan a spol. Strana 9 „Barani“ udreli v závere Banskobystrickí hokejisti vyhrali včera na nitrianskom ľade tretí finálový zápas play-off 3:2 vďaka dvom gólom v záverečnej šesťminútovke – prvý z nich strelil Skalický - a v sérii sa ujali vedenia 2:1 na zápasy. FOTO SITA/MARTIN HAVRAN minút Bez Cibulkovej! Obavy sa, žiaľ, naplnili. Náš fedcupový tím bude cez víkend v bratislavskom NTC bojo- 179 bez gólu vať s Holanďankami o postup do svetovej skupiny bez momentálne štvrtej hráčky Naši hokejisti nestrelili v prípravných zápasoch pred blížiacimi sa MS gól už dlhých svetového rebríčka Dominiky Cibulkovej. 179 minút. Včera prehrali v Košiciach s Fínmi, ktorí prekonali Júliusa Hudáčka FOTO ŠPORT/MILAN ILLÍK trikrát. FOTO ŠPORT/JANO KOLLER Strana 7 Strana 26 Rodine a kamarátovi Čišovskému Stý ligový gól bude Marekovi Bakošovi pripomínať nielen HOKEJOVÁ SÚŤAŽ kopačka, ktorou ho strelil, ale aj lopta, ktorú poslal v nedeľu z penalty do siete Slovácka. „Venujem ho rodine a kamarátovi MÁ SVOJICH Mariánovi Čišovskému,“ vraví slovenský kanonier plzenskej Viktorie. Strana 2 VÝHERCOV! Viac na strane 10 2 FUTBAL štvrtok 20. 4. 2017 MAREK BAKOŠ strelil v nedeľu svoj 100. gól v najvyššej súťaži a stal sa 34. členom Klubu ligových kanonierov Marek Bakoš v zápase Vitaj so Slováckom, v ktorom strelil jubilejný 100. ligový gól. Po odchode Romana Hubníka z ihriska mu okrem ovácií patrila aj kapitánska páska. Po zápase s dcérou Laurou. -

Eriksen.Pdf (1008.Kb)

Campus Elverum Avdeling for helse- og idrettsfag Kandidatnummer 2 Bacheloroppgave Analyse av angrepsstiler i norsk Eliteserie, spansk La Liga, tysk Bundesliga og engelsk Premier League Analysis of attacking styles in norwegian Eliteserie, Spanish La Liga, german Bundesliga and english Premier League Bachelor i idrett- spesialisering i trenerrollen 2014/2017 2017 Samtykker til tilgjengeliggjøring i digitalt arkiv Brage JA ☒ NEI ☐ 2 Forord Dette er den avsluttende oppgaven for min bachelorgrad i Idrett med Spesialisering i Trenerrollen ved Høgskolen i Hedmark avdeling Elverum. Oppgaven min handler om angrepsstiler i toppfotball og problemstillingen min er: Hvilken angrepsstil er mest effektiv i Norsk Eliteserie sammenlignet med de beste ligaene i Europa? Jeg har hele livet vært interessert i taktikk og spillestiler i fotball og når jeg fikk muligheten til å fordype meg i angrepsstiler i fotball ville jeg ikke la den muligheten gå fra meg. Jeg syntes også at det er veldig interessant med ulike fotballkulturer og nasjonale ulikheter i fotballfilosofi. Derfor ville jeg se nærmere på hvordan vår fotballfilosofi påvirker måten vår å spille fotball på, og om den er så ulik de beste nasjonene i Europa som det kan se ut som ved første øyekast. Midtveis i arbeidet fikk jeg også vite at Egil «Drillo» Olsen skrev om det samme temaet som jeg skriver om, når han skrev sin hovedoppgave under studiet Norges Idrettshøgskole. Det syns jeg var veldig stas og det ga meg ekstra motivasjon til å gjøre en bra oppgave. Jeg vil takke venner og familie for bra støtte både gjennom arbeidet med denne oppgaven og gjennom disse tre årene i Elverum. -

Public Version

EUROPEAN COMMISSION Brussels, 06.10.2020 C(2020) 6968 final PUBLIC VERSION In the published version of this decision, some information has been omitted pursuant to Article 17(2) of Council Regulation (EC) No 139/2004 concerning non-disclosure of business secrets and other confidential information. The omissions are shown thus […]. Where possible the information omitted has been replaced by ranges of figures or a general description. To the notifying party Subject: Case M.9669 – PPF GROUP / CENTRAL EUROPEAN MEDIA ENTERPRISES Commission decision pursuant to Article 6(1)(b) of Council Regulation No 139/20041 and Article 57 of the Agreement on the European Economic Area2 Dear Sir or Madam, (1) On 1 September 2020, the European Commission received notification of a proposed concentration pursuant to Article 4 of the Merger Regulation by which PPF Group N.V. ("PPF" or the "Notifying Party", Netherlands) proposes to acquire within the meaning of Article 3(1)(b) of the Merger Regulation sole control of the whole of Central European Media Enterprises Ltd. ("CME", Bermuda) (the “Transaction”).3. PPF and CME are collectively referred to as the "Parties". 1 OJ L 24, 29.1.2004, p. 1 (the “Merger Regulation”). With effect from 1 December 2009, the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union (“TFEU”) has introduced certain changes, such as the replacement of “Community” by “Union” and “common market” by “internal market”. The terminology of the TFEU will be used throughout this decision. 2 OJ L 1, 3.1.1994, p. 3 (the “EEA Agreement”). 3 Publication in the Official Journal of the European Union No C 299, 09.09.2020, p. -

Azarenka, Victoria Chirico, Louisa Kudla, Denis Ferrer, David

LIVE Mi 14:40 WTA, Madrid ... Azarenka, Victoria Chirico, Louisa Mi 15:20 ATP, Madrid ... Kudla, Denis Ferrer, David Mi 15:55 WTA, Madrid ... Cibulkova, Dominika Pavlyuchenkova, Mi 16:00 ATP, Madrid Teledeporte Djokovic, Novak Coric, Borna Mi 16:40 ATP, Madrid ... Cuevas, Pablo Monfils, Gael Mi 17:00 AFC Champ., League, Gruppe A ... Sepahan AL Ittihad Ksa Mi 17:30 Basketball, Türkei, TBL NTV Spor Galatasaray Turk Telekom Mi 18:30 Basketball, VTB United League, Playoffs Sport kLub 3 Nymburk CSKA Moskau Mi 19:00 Basketball, Rumänien, Liga Nationala P.Off Digi Sport 3 Steaua BC Mures Mi 19:45 Türkei, Cup ATV Turkey Galatasaray Rizespor Mi 20:00 ATP, Madrid ... DEL Potro, Juan Sock, Jack Mi 20:30 Basketball, Italien, A1 Sport Klub 2 Caserta Trento Mi 20:30 Basketball, Spanien, ACB C + Deportes Laboral Kutxa Joventut Mi 20:45 Champions League Club RTL Real Madrid Man. City Do 15:30 Schweden, Cup Fox Sports 2 Malmo Häcken Do 17:00 Dänemark, Cup Sport Klub 3 Aarhus FC Copenhagen Do 18:15 Türkei, Cup ATV Turkey Fenerbahce Konyaspor 04.05.2016. 10:40 Seite 1 von 3 Do 21:05 UEFA, Europa League Arena Sport 4 Sevilla Shakhtar Donetsk Do 21:05 UEFA, Europa League Arena Sport 3 Liverpool Villarreal Fr 18:30 Russland, Premier League Sport Klub 3 Rostov Lok. Moskau Fr 20:30 Belgien, Championship Round NTV Spor Genk Zulte Waregem Sa 12:30 Türkei, Süper Lig LIG TV Sivasspor Genclebirligi Sa 13:30 Russland, Premier League Sport TV2 CSKA Moskau Terek Grozny Sa 13:30 England, Championship Diema Sport Middlesbrough Brighton Sa 13:45 England, Premier League Fox Sports 2 Norwich Man. -

2021 IIHF Ice Hockey World Championship, Latvia Broadcast Partners List

2021 IIHF Ice Hockey World Championship, Latvia Broadcast Partners List 20.05.2021 / Subject to change RIGHTS PROVISION Region Licensed Territory/ies Broadcaster TV TV RADIO NEWS MOBILE INTERNET BROADBAND HIGHLIGHTS Africa Angola, Burundi, Benin, Botswana, Burkina Faso, Cameroon, Central African Republic, Chad, Congo, Cape Verde, Cote d'lvoire, Democratic Republic of Congo, Djibouti, Equatorial Guinea, Eritrea, Ethiopia, Gabon, Gambia, Ghana, Guinea, Guinea Bissau, Kenya, Lesotho, Liberia, Madagascar, Malawi, Mozambique, Mali, Mauritania, Namibia, Nigeria, Niger, Rwanda, South Africa, Eswatini, São Tome and Principe, St Helena and Ascension, Senegal, Sierra Leone, Socotra, Tanzania, Togo, Uganda, Zimbabwe, Zambia SuperSport X X X X X Comoros, Mauritius, Mayotte, Réunion, Seychelles L'Equipe X SuperSport X X X X X Asia China CCTV X X Chinese Taipei Elta X X X X X Korea Republic SBS Korea X Macau TDM Macau X Philippines TAP Sports Philippines X Singapore Singtel X Caribbean Anguilla, Antigua & Barbuda, Aruba, Barbados, Bonaire, British Virgin Islands, Cayman Islands, Curaçao, Dominica, Grenada, Guadelupe, Haiti, Jamaica, Martinique, Montserrat, Saba, Saint Kitts and Nevis, Saint Lucia, Saint Vincent and the Grenadines, St. Barth, St. Eustatius, Trinidad and Tobago, Turks and Caicos Islands DIRECTV X Bermuda, Cayman Islands, Puerto Rico, US Virgin Islands NHL Network X X X X X ESPN+ X Dominican Republic, Guadelupe, Haiti, Martinique, St. Barth, St. Martin, Trinidad and Tobago L'Equipe X Europe Andorra L'Equipe X Austria ORF TV X X X Belarus -

Príďte Na Nás!

Štvrtok 25 rokov tipovania na Slovensku nike.sk 10. 11. 2016 NAJLEPŠIE KURZY – SUPERŠANCA 1 X 2 70. ročník • číslo 261 13778 N. GOMBOS – C.-M. STEBE 1,43 2,55 10:00 cena 0,60 14036 UFA – NIŽNEKAMSK 1,70 4,50 4,40 15:00 13784 KAZAŇ – CZ BELEHRAD 1,38 16,7 3,65 17:00 14038 IFK HELSINKI – ÄSSÄT PORI 1,68 4,50 4,15 17:30 14037 SLOVENSKO 20 – BANSKÁ BYSTRICA 14,0 9,30 1,12 18:00 384 URUGUAJ – EKVÁDOR 1,63 4,00 5,70 Pi 0:00 7019 VENEZUELA – BOLÍVIA 1,62 4,10 5,60 Pi 0:30 14034 TAMPA BAY – NY ISLANDERS 1,94 4,00 3,70 Pi 1:35 App Store pre iPad a iPhone / Google Play pre Android 13770 MONTREAL – LOS ANGELES 2,05 3,80 3,40 Pi 1:35 VLADIMÍR WEISS priznáva, že urobil niečo, čo urobiť nemal, ale nemieni zo seba robiť hlupáka, a dodáva: Strana 3 Stojím o priazeň fanúšikov Strana 20 Do Londýna za Djokovičom Marián Vajda v utorok sledoval v hľadisku bratislavského NTC spolu s dcé- rou Nikolou duel svojej ďalšej ratolesti Natálie na turnaji ITF Slovak Indoor Príďte Strana 2 a dnes letí za svojím zverencom Novakom Djokovičom do Londýna na turnaj majstrov. „Hoci tituly sú preňho dôležitejšie ako prvé miesto vo svetovom na nás! rebríčku, chce sa naň vrátiť,“ vraví okrem iného. FOTO JANO KOLLER „Ak Litva nie je pre vás atraktívne mužstvo, príďte na nás,“ odkazuje slovenským futbalovým fanúšikom v pred- večer nášho štvrtého zápasu v kvalifikácii MS 2018 sto- pér Milan Škriniar. -

TV DISTRIBUTION 41 171 International Broadcasters Territories

TV DISTRIBUTION 41 171 International Broadcasters Territories Household Across five reach of 682 continents million HOST BROADCASTERS Event Country Broadcaster Logo Brasilia Open Brasil Globo TV Olympic Bay Sanya Open China Sanya Hainan TV Silesia Open Poland Polsat Shanghai Grand Slam China Great Sports Channel Beijing Grand Slam China CCTV Patria Direct Prague Open Czech Republic Czech TV Moscow Grand Slam Russia NTV+ Smart Grand Slam Italy Italy RAI 1 to 1 Energy Grand Slam Switzerland SRG Smart Grand Slam Germany Sport1 A1 Grand Slam, Austria ORF Mazury Orlen Grand Slam Poland Polsat Paf Open Finland MTV 3 Bangsaen Thailand Open Thailand NBT- Sport INTERNATIONAL BROADCASTERS/ASIAPAC REGION BROADCASTER COUNTRY LOGO HOME REACH Fox Sport Australia 2,200,000 Astro Measat Malaysia & Brunei 1,800,000 Sky NZ New Zealand 750,000 Starhub Singapore 500,000 Asia Pacific PCCW Hong Kong 900,000 TEN SPORT Indian Subcontinent 80,000,000 KBS Korea 15,000,000 Youku internet China Qiyi internet ABS Philippines 2,000,000 True Vision Thailand 800,000 INTERNATIONAL BROADCASTERS/AMERICAS REGION BROADCASTER COUNTRY LOGO HOME REACH Televisa Mexico and Central America 5,200,000 The Americas DirecTV South America 4,000,000 RDS Canada 2,300,000 Globo Brazil 46,000,000 Universal USA 50,000,000 INTERNATIONAL BROADCASTERS/EUROPE 1 Region Broadcaster Country Logo Home reach Austria ORF Liechtenstein 3,462,000 TV3 Catalunya 2,500,000 Czech TV Czech Republic 3,800,000 Finland, Sweden, Viasat Norway, Denmark 3,000,000 BeINSport France 350,000 Europe Sport 1 Germany -

The World Games 2017

GSI Event Study The World Games 2017 Wrocław, Poland 20 July – 30 July 2017 GSI EVENT STUDY / THE WORLD GAMES 2017 GSI Event Study The World Games 2017 Wrocław, Poland This Event Study is subject to copyright agreements. No part of this Event Study PUBLISHED JANUARY 2018 may be reproduced distributed or transmitted in any form or by any means BY SPORTCAL GLOBAL or stored in any retrieval system of any nature without prior written permission. COMMUNICATIONS LTD Application for permission for use of copyright material shall be made to Sportcal Global Communications Ltd (“Sportcal”). Sportcal has prepared this Event Study using reasonable skill, care and diligence Author for the sole and confidential use of the International World Games Association (“IWGA”) and the Wrocław Organising Committee The World Games 2017 Krzysztof Kropielnicki (“WOC”) for the purposes set out in the Event Study. Sportcal does not assume or accept or owe any responsibility or duty of care to any other person. Any use that a third party makes of this Event Study or reliance thereon or any decision Research and editorial support made based on it, is the responsibility of such third party. Edward Frain, Andrew Horsewood, Mike The Event Study reflects Sportcal’s best judgement in the light of the information Laflin, Beth McGuire, Callum Murray, available at the time of its preparation. Sportcal has relied upon the completeness, Gabriella Orlich, Tim Rollason, Colin accuracy and fair presentation of all the information, data, advice, opinion Stewart or representations (the “Information”) obtained from public sources and from IWGA, WOC and various third-party providers.