Electoral Alliances and Majority Versus Minority Communalism

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

SIKH TIMES WEBSITE PAGE.Qxd

instagram.com/ @thesikhtimes facebook.com/ thesikhtimes qaumipatrika VISIT: PUBLISHED FROM Delhi, Haryana, Uttar www.thesikhtimes.in Pradesh, Punjab, The Sikh Times Email:[email protected] Chandigarh, Himachal and Jammu National Daily Vol. 12 No. 311 RNI NO. DELENG/2008/25465 New Delhi, Sunday, 21 March, 2021 [email protected] 9971359517 12 pages. 2/- Ajit Doval, US Defence Secretary Fire breaks out on Delhi-Lucknow Discuss Strategic Partnership Shatabdi Express at Ghaziabad station Delhi-Lucknow Shatabdi luggage compartment caught fire on Saturday (March 20) morning at Ghaziabad railway station. The authorities are yet to ascertain the cause of the fire. Simmi Kaur Babbar New Delhi. Delhi-Lucknow Shatabdi General Manager Northern New Delhi. National Security defense partnership, as we work luggage compartment caught fire on Railway. Advisor Ajit Doval and US together to address the most Saturday (March 20) morning at Additionally, earlier this month, nine Secretary of Defence Lloyd pressing challenges facing the ! Delhi-Lucknow Ghaziabad railway station. The people lost their lives, which James Austin III on Friday Indo-Pacific region," he said. authorities are yet to ascertain the included rail staffers and fire discussed areas of mutual Earlier in the day, Austin met interest, strategic partnership Shatabdi luggage cause of the fire. No injury or casualty officials in a fire that broke out on Prime Minister Narendra Modi and cooperation on various and expressed America''s strong compartment has been reported so far. the 13th floor of the Eastern aspects of security and defence, desire to further enhance the caught fire on The incident comes a week after a Railway’s office in Kolkata. -

Don't Talk About Khalistan but Let It Brew Quietly. Police Say Places Where Religious

22 MARCH 2021 / `50 www.openthemagazine.com CONTENTS 22 MARCH 2021 5 6 12 14 16 18 LOCOMOTIF bengAL DIARY INDIAN ACCENTS TOUCHSTONE WHISPERER OPEN ESSAY The new theology By Swapan Dasgupta The first translator The Eco chamber By Jayanta Ghosal Imperfect pitch of victimhood By Bibek Debroy By Keerthik Sasidharan By James Astill By S Prasannarajan 24 24 AN EAST BENGAL IN WEST BENGAL The 2021 struggle for power is shaped by history, geography, demography—and a miracle by the Mahatma By MJ Akbar 34 THE INDISCREET CHARM OF ABBAS SIDDIQUI Can the sinking Left expect a rainmaker in the brash cleric, its new ally? By Ullekh NP 38 A HERO’S WELCOME 40 46 Former Naxalite, king of B-grade films and hotel magnate Mithun Chakraborty has traversed the political spectrum to finally land a breakout role By Kaveree Bamzai 40 HARVESTING A PROTEST If there is trouble from a resurgent Khalistani politics in Punjab, it is unlikely to follow the 50 54 roadmap of the 1980s By Siddharth Singh 46 TURNING OVER A NEW LEAF The opportunities and pains of India’s tiny seaweed market By Lhendup G Bhutia 62 50 54 60 62 65 66 OWNING HER AGE THE VIOLENT INDIAN PAGE TURNER BRIDE, GROOM, ACTION HOLLYWOOD REPORTER STARGAZER Pooja Bhatt, feisty teen Thomas Blom Hansen The eternity of return The social realism of Viola Davis By Kaveree Bamzai idol and magazine cover on his new book By Mini Kapoor Indian wedding shows on her latest film magnet of the 1990s, is back The Law of Force: The Violent By Aditya Mani Jha Ma Rainey’s Black Bottom By Kaveree Bamzai Heart of Indian Politics -

Do Socio-Economic Conditions Influence Dynastic Politics? Initial Evidence from the 16Th Lok Sabha of India

WORKING PAPER Do Socio-Economic Conditions Influence Dynastic Politics? Initial Evidence from the 16th Lok Sabha of India Ronald U. Mendoza AIM Rizalino S. Navarro Policy Center for Competitiveness Jan Fredrick P. Cruz AIM Rizalino S. Navarro Policy Center for Competitiveness Unnikrishnan Alungal MDM Batch 2014 AIM Stephen Zuellig Graduate School of Development Management RSN-PCC WORKING PAPER 15-011 ASIAN INSTITUTE OF MANAGEMENT RIZALINO S. NAVARRO POLICY CENTER FOR COMPETITIVENESS WORKING PAPER Do Socio-Economic Conditions Influence Dynastic Politics? Initial Evidence from the 16th Lok Sabha of India Ronald U. Mendoza AIM Rizalino S. Navarro Policy Center for Competitiveness Jan Fredrick P. Cruz AIM Rizalino S. Navarro Policy Center for Competitiveness Unnikrishna Alungal MDM Batch 2014 AIM Stephen Zuellig Graduate School of Development Management AUGUST 2015 The authors would like to thank Dr. Sounil Choudhary of the University of Delhi; Dr. Kripa Ananthpur of the Madras Institute of Development Studies; Ms. Chandrika Bahadur of the Sustainable Development Solutions Network; Mr. Appu Lenin of the Jawaharlal Nehru University; and Mr. Siddharth Singh of the Centre for Research on Energy Security for helpful comments on an earlier draft. This working paper is a discussion draft in progress that is posted to stimulate discussion and critical comment. The views expressed herein are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of Asian Institute of Management. Corresponding authors: Ronald U. Mendoza, AIM Rizalino S. Navarro Policy Center for Competitiveness Tel: +632-892-4011. Fax: +632-465-2863. E-mail: [email protected] Jan Fredrick P. Cruz, AIM Rizalino S. Navarro Policy Center for Competitiveness Tel: +632-892-4011. -

Download Liberation April 2021

COVER STORY APRIL 2021 CENTRAL ORGAN OF CPI(ML) Rs. 25 COVER STORY MLAs Brutally Beaten Inside Bihar Assembly, Police Raj Act Passed The first use of the Bihar Special Armed Police Bill 2021 was perpetrated inside the Bihar Assembly itself on 23 March. Shattering all rules and traditions of the constitutional and parliamentary system, police and goons entered the Assembly, brutally beat up opposition MLAs and pushed them out, after which BJP-JDU passed the draconian Bihar Special Armed Police Bill 2021 changing Bihar into a Police Raj. Earlier, when the Assembly session commenced on 23 March the Opposition started protesting against the Police Raj Bill. The session was adjourned a few times due to opposition protests, and proceedings were obstructed throughout the day. At 5 pm before the session was to end, a large number of RAF police personnel were called inside the Assembly on the orders of the Speaker and the government. Marshals were of course already present. The Bihar DGP, Patna SSP and DM jointly oversaw the beating, kicking, fisticuffing of MLAs as they were pushed and dragged out of the Assembly. The SSP and DM were themselves among those who did the brutal beating. The entire Assembly was filled with police personnel and the Police Raj Act was passed in the complete absence of the Opposition. Journalists were also beaten up. Leader of CPIML legislative party Comrade Mahboob Alam's arm was twisted and wrenched. Comrade Sudama Prasad was pushed and shoved and he fell down the stairs, causing a serious finger injury. A CPIM MLA was so badly beaten up that he lost consciousness. -

2021 Manifesto of the Left Front the Backdrop of the Election the Dates for the West Beng

P a g e | 1 17th Assembly Election in West Bengal: 2021 Manifesto of the Left Front The Backdrop of the Election The dates for the West Bengal State Assembly elections have been announced. We are all aware that for the last one year or so, the struggle of human civilization against the corona pandemic has been going on. Our daily life as well as our movements and struggles are being conducted following all necessary precautions. In this situation, between March 27 and April 29 elections will be held in eight phases in the state of West Bengal. For the large majority of the people of the state this election is the battle for restoring democracy, the battle to end mis- governance and anarchy in the state. For the last ten years the Trinamool Congress party and its government has been running a regime of authoritarian terror in the state. Democratic voices have been throttled in a dictatorial manner. On the one hand, nepotism, corruption, extortion, syndicate rule have been unleashed and on the other hand, attacks have come down on workers, peasants, students, youth and women. Minorities, Scheduled Castes and Indigenous Peoples are similarly under attack. In the forthcoming assembly elections, the people have to concentrate all their strength to bring an end to this disastrous TrinamuIi regime. The Narendra Modi-led RSS-BJP government at the Centre are enforcing agricultural laws and restructuring labour laws all in the interest of corporate business alone. They are relentlessly implementing neo-liberal policies. The lives of ordinary people, including workers and peasants, have become miserable. -

Party Position in 16Th Lok Sabha

Party Position in 16th Lok Sabha SS, 18 BJD, 20 BJP, 281 TMC, 34 AIADMK, 37 INC, 44 Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) (281) Indian National Congress INC(44) All India Anna Dravida Munnetra Kazhagam (AIADMK) (37) All India Trinamool Congress (TMC)(34) Biju Janata Dal (BJD) (20) Shivsena (SS)(18) Telugu Desam (TDP)(16) Telangana Rashtra Samithi (TRS)(11) Communist Party of India (Marxist) CPI(M) (9) Yuvajana Sramika Rythu Congress Party (YSRCP)(9) Nationalist Congress Party (6) Lok Jan Shakti Party (6) Samajwadi Party (5) Aam Aadmi Party (4) Rashtriya Janata Dal (4) Shiromani Akali Dal (4) All India United Democratic Front (3) Jammu & Kashmir Peoples Democratic Party (3) Rashtriya Lok Samta Party (3) Independents (3) Indian National Lok Dal (2) Indian Union Muslim League (2) Janata Dal (Secular) (2) Janata Dal (United) (2) Jharkhand Mukti Morcha (2) Apna Dal (2) Communist Party of India (1) All India N.R. Congress (1) Kerala Congress (M) (1) Naga Peoples Front (1) National Peoples Party (1) Pattali Makkal Katchi (1) Revolutionary Socialist Party (1) Sikkim Democratic Front (1) All India Majlis-E-Ittehadul Muslimeen (1) Swabhimani Paksha (1) AS ON 19.02.2015 Women Members in 16th Lok Sabha Female (66) 12% Male (476) Female (66) Male (476) 88% Party-wise list of Women Members in 16th Lok Sabha 1 Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP,32) 2 All India Trinamool Congress (AITMC,13) 3 Indian National Congress (INC,4) 4 All India Anna Dravida Munnetra Kazhagam (AIADMK,4) 5 Biju Janata Dal (BJD,3) 6 Yuvajana Sramika Rythu Congress Party (YSRCP,2) 7 Jammu and Kashmir Peoples Democratic Party (1) 8 Communist Party of India (Marxist) (1) 9 Telangana Rashtra Samithi (1) 10 Shiv Sena (1) 11 Nationalist Congress Party (1) 12 Lok Jan Shakti Party (1) 13 Samajwadi Party (1) 14 Shiromani Akali Dal (1) 15 Apna Dal (1) . -

BJP) Than Men

Gender Gap and Gender Differences in National Party Choices in Indian General Election, 2014 by Srijani Datta M.A., Jawaharlal Nehru University, New Delhi, 2011 B.A., St. Xavier’s College Autonomous, Calcutta, 2009 Project Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts in the Department of Political Science Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences © Srijani Datta 2019 SIMON FRASER UNIVERSITY Fall 2019 Copyright in this work rests with the author. Please ensure that any reproduction or re-use is done in accordance with the relevant national copyright legislation. Approval Name: Srijani Datta Degree: Master of Arts (Political Science) Title: Gender Gap and Gender Differences in National Party Choices in Indian General Election, 2014 Examining Committee: Chair: Eline de Rooij Associate Professor Eline de Rooij Senior Supervisor Associate Professor Steven Weldon Supervisor Associate Professor Laurel Weldon External Examiner Professor Date Defended/Approved: Dec 03, 2019 ii Abstract Traditionally, Indian women have been more likely to vote for the Indian National Congress (INC) compared to the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) than men. In this paper, I draw from the Developmental Theory of Modern Gender Gap on party choices to formulate hypotheses about the socio-demographic factors and gender differences in attitudes that could have led to the gender gap in party choices in the 2014 election. I test these hypotheses by conducting statistical analysis of data from Wave 6 of the World Value Survey. My research shows that contrary to the modern gender gap theory, the gender advantage of India’s centre-left party comes from states with low levels of human development in comparison to more developed states. -

Cattle-Smuggling Case: CBI Issues Lookout Notice Against TMC Leader's

WWW.YUGMARG.COM FOLLOW US ON REGD NO. CHD/0061/2006-08 | RNI NO. 61323/95 Join us at telegram https://t.me/yugmarg Sunday March 7, 2021 CHANDIGARH, VOL. XXVI, NO. 37 PAGES 8, RS. 2 YOUR REGION, YOUR PAPER Cattle-smuggling Govt ready to amend new agri case: CBI issues lookout notice against Supreme Court laws; opposition playing politics hybrid physical hearing from TMC leader’s brother March 15 AGENCY tion (CBI) named Binay Mishra as a NEW DELHI, MARCH 6 co-accused in its supplementary NEW DELHI: The chargesheet filed in the cattle-smug- Supreme Court, which is at cost of agri-economy: Tomar The CBI has issued a lookout notice gling case last month. hearing cases through against Bikas Mishra, brother of Tri- Binay Mishra is believed to be video-conferencing since AGENCY namool Congress (TMC) leader Bi- very close to West Bengal Chief Min- March last year due to the NEW DELHI, MARCH 6 nay Mishra who is a confidant of par- ister and TMC supremo Mamata pandemic, will commence ty MP Abhishek Banerjee, in a cattle- Banerjee’s nephew Abhishek Baner- hybrid physical hearing Agriculture Minister Narendra Singh Tomar smuggling case, officials said on Sat- jee, the officials said. from March 15 for which it on Saturday said the government is ready to urday. In its chargesheet filed before a has issued the standard operating procedure. Sev- amend three new farm laws to respect the sen- The agency is also contemplating special CBI court in West Bengal’s eral Bar bodies and timents of protesting farmers, even as he at- to approach the Interpol to get a Red Asansol, the agency has already lawyers have been de- tacked opposition parties for doing politics on Corner Notice issued against Binay shown Binay Mishra as absconding. -

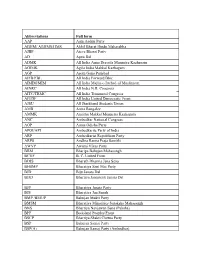

Abbreviations Full Form AAP Aam Aadmi Party ABHM

Abbreviations Full form AAP Aam Aadmi Party ABHM/ ABHMS/HMS Akhil Bharat Hindu Mahasabha AJBP Ajeya Bharat Party AD Apna Dal ADMK All India Anna Dravida Munnetra Kazhagam AGIMK Agila India Makkal Kazhagam AGP Asom Gana Parishad AIFB/FBL All India Forward Bloc AIMIM/MIM All India Majlis-e-Ittehad-ul Muslimeen AINRC All India N.R. Congress AITC/TRMC All India Trinamool Congress AIUDF All India United Democratic Front AJSU All Jharkhand Students Union AMB Amra Bangalee AMMK Anaithu Makkal Munnetra Kazhagam ANC Ambedkar National Congress AOP Aama Odisha Party APOI/API Ambedkarite Party of India ARP Ambedkarist Republican Party ARPS Andhra Rastra Praja Samithi AWVP Awami Vikas Party BBM Bharipa Bahujan Mahasangh BCUF B. C. United Front BDJS Bharath Dharma Jana Sena BHSMP Bharatiya Sant Mat Party BJD Biju Janata Dal BJJD Bhartiya Jantantrik Janata Dal BJP Bharatiya Janata Party BJS Bharatiya Jan Sangh BMP /BMUP Bahujan Mukti Party BMSM Bharatiya Minorities Suraksha Mahasangh BNS Bhartiya Navjawan Sena (Paksha) BPF Bodoland Peoples Front BSCP Bhartiya Shakti Chetna Party BSP Bahujan Samaj Party BSP(A) Bahujan Samaj Party (Ambedkar) BVA Bahujan Vikas Aaghadi BVM Bharat Vikas Morcha CMP/CMP (J) Communist Marxist party Cong(S) Congress (Secular) CPI Communist Party of India CPI(ML) Red Star Communist Party of India (Marxist-Leninist) Red Star CPIML (L) Communist Party of India (Marxist–Leninist) Liberation CPM Communist Party of India (Marxist) DABP Dalita Bahujana Party DJP Delhi Janta Party DMDK Desiya Murpokku Dravida Kazhagam DMK Dravida Munnetra -

Bengal, Assamvote

OUR EDITIONS: JAIPUR, AHMEDABAD & LUCKNOW www.fi rstindia.co.in www.fi rstindia.co.in/epaper/ twitter.com/thefi rstindia facebook.com/thefi rstindia instagram.com/thefi rstindia JAIPUR l SUNDAY, MARCH 28, 2021 l Pages 12 l 3.00 RNI NO. RAJENG/2019/77764 l Vol 2 l Issue No. 291 HAPPY HOLIDAY NOTICE The press and offi ces of First India will remain closed on March 28 and 29, 2021, on account of Holi. There will, therefore, be no edition As devotees throng the Sri Bankey Bihari temple in Vrindavan to celebrate Holi, on Saturday, all corona protocols of the paper on March 29 and 30, were put aside, as many were seen without face masks and 2021. Wishing all our readers a social distancing too was absent. —PHOTO BY PTI very happy & safe Holi. —Editor Sachin tests covid positive, India, Bangladesh sign five Bengal, Assam vote now in home MoUs to further enhance ties quarantine Addressing the Matua community, PM Modi said both India and Bangladesh want to see peace, stability and love in world Dhaka: India and Bang- ladesh on Saturday their heart out signed five MoUs to fur- ther enhance bilateral Nearly 80% turnout in Bengal, 72% in Assam in 1st phase ties between the two na- tions during Prime Kolkata/Guwahati: Mumbai: Former In- Minister Narendra Voting was held in a total TMC ALLEGES dian cricketer Sachin Modi delegation-level of 77 seats — 47 in Assam Tendulkar has tested meeting with his Bang- and 30 in West Ben- ‘POLL RIGGING’ positive for COVID-19. -

Delhi

. / C& 3 $'%D %D D !"#$ +#",+&-./ -#++-$ -'12 %#-'(0 !883( &:&8"!8 !&83"(G(! !;&!8 ;8" 38:;:< 29 ; :;<8"9! " 88 ;"628 !88!78"&8#;&; ! ;! <! ;3#!; : 8&8"G<"8! 8 38;!3< ;G38!3B6G93 E: )*-+ ++' ), E " 8 $ 0 1 -1232-4 -2 !" # 8938:; !)*(+,-% 8938:; ndia is all set to roll out the Isecond phase of the vaccina- & 25-year-old woman, who tion drive from Monday to vac- 7 $+.=)> Awas carrying her two-year- cinate people aged above 60 >? old daughter, was stabbed to years and 45 years with co- -@ death for resisting a chain- morbidities in private and ' snatching bid in Northwest Government hospitals in the ++@,.=-+ " Delhi’s Adarsh Nagar, police backdrop of worrying upward & < ; ( said on Sunday, adding that trends shown by Covid-19. they have arrested the accused The country reported a involved in the Saturday (9:30 single-day rise of 16,752 cases '$$ pm) incident. in the last 24 hours, the high- $ A CCTV footage of the est in the last 30 days, taking incident went viral on social the overall tally to 1,10,96,731 media. In the video, two on Sunday, said the Union ' women can be seen walking Health Ministry, hoping that $ when a man chases them and the accelerated vaccination tries to snatch the victim’s drive will help make people safe 9>%@ chain from behind. The from the infection. & woman — identified as Simran The Covid-19 vaccine will " Kaur — chases him, following be given free of cost at < #$ which he falls on the road. Government hospitals, while ! Thereafter, he stands up and ! "#$ $ & people will need to pay for it at $ B stabs the woman. -

Full of Facebook Users' 8 P.M

y k y cm RAKUL’S PHILOSOPHY ‘KILL THE BILL’ PROTESTS SHINING STAR Actor Rakul Preet Singh says that 107 people were arrested after clashes between cops Odisha para- badminton player Pramod one needs to love as long as and demonstrators at a “Kill the Bill” protest in Bhagat wins singles and doubles gold at Dubai tournament one lives LEISURE | P2 central London INTERNATIONAL | P10 SPORTS | P12 VOLUME 11, ISSUE 5 | www.orissapost.com BHUBANESWAR | MONDAY, APRIL 5 | 2021 12 PAGES | `4.00 22 jawans killed in anti-Naxal ops, 1 missing VISUALS FROM THE SPOT SHOWED BODIES OF THE SLAIN JAWANS LYING IN THE FIELD AND ON THE VILLAGE STREETS AGENCIES BIJAPUR MAOIST ATTACK Raipur, April 4: Police recovered bul- WHO IS MAOIST let-riddled bodies of 20 jawans in the he anti-Naxal operation was jungles of Chattisgarh Sunday, raising Tlaunched based on the LEADER HIDMA? to 22 the number of security person- intelligence inputs about the nel killed in a fierce gun battle with presence of Maoists of PLGA BJP warns impeachment Naxals the previous day – the biggest (Peoples’ Liberation Guerilla Army) massacre in more than a year that Battalion No. 1 also left 31 injured. he Naxals, around 400 in number, motion against Speaker Police also recovered the bodies of Twere strategically positioned on a three jawans killed in the encounter, hillock in front of Tekalguda village POST NEWS NETWORK parties to speak and raise im- an official said, adding a search op- and around it portance issues of public eration is on in the forest to trace a miss- Bhubaneswar, April 4: interest,” Naik said.