I VESUVIUS at HOME by CHRISTIN ELIZABETH TURNER B.A

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Last Year at Marienbad Redux

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE: Last Year at Marienbad redux Allan Sekula and Noël Burch. Still from Reagan Tape, 1981, single-channel video, color, sound, 10 min. 39 sec., edition of 5 © Allan Sekula and Noël Burch, Courtesy of the artists and Christopher Grimes Gallery, Santa Monica September 12 – October 26, 2013 Opening Reception: Thursday, September 12, 6-8 pm EFA Project Space Curated by James Voorhies th nd produced by Bureau for Open Culture 323 West 39 Street, 2 floor New York, NY 10018 between 8th and 9th Avenues Participating Artists and Writers: Jennifer Allen, Keren Cytter, Tacita Dean, Jessamyn Fiore, Dan Fox, Gallery Hours: Wed through Sat, 12-6 pm Jens Hoffmann, Iman Issa, David Maljković, Ján T. 212-563-5855 x 244 Mančuška, Gordon Matta-Clark, Josh Tonsfeldt, Allan [email protected] Sekula & Noël Burch, and Maya Schweizer www.efanyc.org /////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////// Last Year at Marienbad redux is an exhibition, public program and publication that together examine how fictional narratives develop over time to form accepted knowledge of people, places, events and things. Inspired by the unconventional cinematic techniques such as nonlinear narrative and repetitive language used in the 1961 film Last Year at Marienbad (directed by Alain Resnais, with screenplay by Alain Robbe-Grillet), the exhibition Last Year at Marienbad redux features works of art that deploy these and other devices⎯⎯editing, character development, plot, mise-en-scène and montage⎯⎯to disrupt, challenge and conflate what is understood as fact and fiction. The project explores how memory, meaning and, ultimately, an understanding of reality are shaped. Last Year at Marienbad redux will bring together work by nine international contemporary artists whose practices engage with the technical and conceptual qualities of cinema. -

The Altering Eye Contemporary International Cinema to Access Digital Resources Including: Blog Posts Videos Online Appendices

Robert Phillip Kolker The Altering Eye Contemporary International Cinema To access digital resources including: blog posts videos online appendices and to purchase copies of this book in: hardback paperback ebook editions Go to: https://www.openbookpublishers.com/product/8 Open Book Publishers is a non-profit independent initiative. We rely on sales and donations to continue publishing high-quality academic works. Robert Kolker is Emeritus Professor of English at the University of Maryland and Lecturer in Media Studies at the University of Virginia. His works include A Cinema of Loneliness: Penn, Stone, Kubrick, Scorsese, Spielberg Altman; Bernardo Bertolucci; Wim Wenders (with Peter Beicken); Film, Form and Culture; Media Studies: An Introduction; editor of Alfred Hitchcock’s Psycho: A Casebook; Stanley Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey: New Essays and The Oxford Handbook of Film and Media Studies. http://www.virginia.edu/mediastudies/people/adjunct.html Robert Phillip Kolker THE ALTERING EYE Contemporary International Cinema Revised edition with a new preface and an updated bibliography Cambridge 2009 Published by 40 Devonshire Road, Cambridge, CB1 2BL, United Kingdom http://www.openbookpublishers.com First edition published in 1983 by Oxford University Press. © 2009 Robert Phillip Kolker Some rights are reserved. This book is made available under the Cre- ative Commons Attribution-Non-Commercial 2.0 UK: England & Wales Licence. This licence allows for copying any part of the work for personal and non-commercial use, providing author -

The Creative Process

The Creative Process THE SEARCH FOR AN AUDIO-VISUAL LANGUAGE AND STRUCTURE SECOND EDITION by John Howard Lawson Preface by Jay Leyda dol HILL AND WANG • NEW YORK www.johnhowardlawson.com Copyright © 1964, 1967 by John Howard Lawson All rights reserved Library of Congress catalog card number: 67-26852 Manufactured in the United States of America First edition September 1964 Second edition November 1967 www.johnhowardlawson.com To the Association of Film Makers of the U.S.S.R. and all its members, whose proud traditions and present achievements have been an inspiration in the preparation of this book www.johnhowardlawson.com Preface The masters of cinema moved at a leisurely pace, enjoyed giving generalized instruction, and loved to abandon themselves to reminis cence. They made it clear that they possessed certain magical secrets of their profession, but they mentioned them evasively. Now and then they made lofty artistic pronouncements, but they showed a more sincere interest in anecdotes about scenarios that were written on a cuff during a gay supper.... This might well be a description of Hollywood during any period of its cultivated silence on the matter of film-making. Actually, it is Leningrad in 1924, described by Grigori Kozintsev in his memoirs.1 It is so seldom that we are allowed to study the disclosures of a Hollywood film-maker about his medium that I cannot recall the last instance that preceded John Howard Lawson's book. There is no dearth of books about Hollywood, but when did any other book come from there that takes such articulate pride in the art that is-or was-made there? I have never understood exactly why the makers of American films felt it necessary to hide their methods and aims under blankets of coyness and anecdotes, the one as impenetrable as the other. -

Memory and Film

MEMORY AND FILM Cinema is obsessed with memory. Time, memory and the past are thematic threads which run through the whole range of film, persistently recurring in national cinemas across the international spectrum. From the popularist mainstream to the obscurest avant-garde – from Steven Spielberg to Andrey Tarkovsky, Alfred Hitchcock to Jean Cocteau, David Lynch to Wong Kar-Wai – it’s difficult to think of a major film artist who hasn’t explored the theme of time, memory and the past. The medium exhibits properties which makes a focus on memory attractive to cinema. The frisson of film, its actuality quality, its ability to pinpoint a moment of time visually and aurally with a visceral immediacy difficult for other mediums. Yet also the sweep of cinema, its ability to move through time and space with the momentum of montage and the evocation of flashback. Cinema can give us an entire life in a few seconds. The fleeting mental images cinema is able to summon – the pictures in the fire – resemble the process of recall itself. Cinema is protective of memory and its veracity. Many films harbour deep suspicion of experiments with memory –Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind (Condry, 2004) and Minority Report (Spielberg, 2002) are examples. I can only think of one movie which guardedly approves of experiments with memory and recall 2 being of potential benefit to mankind – Wim Wenders’ Until the End of the World (1991). Living vicariously through the recall of others is negatively portrayed in dystopian post-apocalyptic narratives such as Blade Runner (Scott, 1982), Strange Days (Bigelow, 1995) and Johnny Mnemonic (Longo, 1996). -

DMAAC – February 1973

LUNAR TOPOGRAPHIC ORTHOPHOTOMAP (LTO) AND LUNAR ORTHOPHOTMAP (LO) SERIES (Published by DMATC) Lunar Topographic Orthophotmaps and Lunar Orthophotomaps Scale: 1:250,000 Projection: Transverse Mercator Sheet Size: 25.5”x 26.5” The Lunar Topographic Orthophotmaps and Lunar Orthophotomaps Series are the first comprehensive and continuous mapping to be accomplished from Apollo Mission 15-17 mapping photographs. This series is also the first major effort to apply recent advances in orthophotography to lunar mapping. Presently developed maps of this series were designed to support initial lunar scientific investigations primarily employing results of Apollo Mission 15-17 data. Individual maps of this series cover 4 degrees of lunar latitude and 5 degrees of lunar longitude consisting of 1/16 of the area of a 1:1,000,000 scale Lunar Astronautical Chart (LAC) (Section 4.2.1). Their apha-numeric identification (example – LTO38B1) consists of the designator LTO for topographic orthophoto editions or LO for orthophoto editions followed by the LAC number in which they fall, followed by an A, B, C or D designator defining the pertinent LAC quadrant and a 1, 2, 3, or 4 designator defining the specific sub-quadrant actually covered. The following designation (250) identifies the sheets as being at 1:250,000 scale. The LTO editions display 100-meter contours, 50-meter supplemental contours and spot elevations in a red overprint to the base, which is lithographed in black and white. LO editions are identical except that all relief information is omitted and selenographic graticule is restricted to border ticks, presenting an umencumbered view of lunar features imaged by the photographic base. -

Appendix I Lunar and Martian Nomenclature

APPENDIX I LUNAR AND MARTIAN NOMENCLATURE LUNAR AND MARTIAN NOMENCLATURE A large number of names of craters and other features on the Moon and Mars, were accepted by the IAU General Assemblies X (Moscow, 1958), XI (Berkeley, 1961), XII (Hamburg, 1964), XIV (Brighton, 1970), and XV (Sydney, 1973). The names were suggested by the appropriate IAU Commissions (16 and 17). In particular the Lunar names accepted at the XIVth and XVth General Assemblies were recommended by the 'Working Group on Lunar Nomenclature' under the Chairmanship of Dr D. H. Menzel. The Martian names were suggested by the 'Working Group on Martian Nomenclature' under the Chairmanship of Dr G. de Vaucouleurs. At the XVth General Assembly a new 'Working Group on Planetary System Nomenclature' was formed (Chairman: Dr P. M. Millman) comprising various Task Groups, one for each particular subject. For further references see: [AU Trans. X, 259-263, 1960; XIB, 236-238, 1962; Xlffi, 203-204, 1966; xnffi, 99-105, 1968; XIVB, 63, 129, 139, 1971; Space Sci. Rev. 12, 136-186, 1971. Because at the recent General Assemblies some small changes, or corrections, were made, the complete list of Lunar and Martian Topographic Features is published here. Table 1 Lunar Craters Abbe 58S,174E Balboa 19N,83W Abbot 6N,55E Baldet 54S, 151W Abel 34S,85E Balmer 20S,70E Abul Wafa 2N,ll7E Banachiewicz 5N,80E Adams 32S,69E Banting 26N,16E Aitken 17S,173E Barbier 248, 158E AI-Biruni 18N,93E Barnard 30S,86E Alden 24S, lllE Barringer 29S,151W Aldrin I.4N,22.1E Bartels 24N,90W Alekhin 68S,131W Becquerei -

Films Shown by Series

Films Shown by Series: Fall 1999 - Winter 2006 Winter 2006 Cine Brazil 2000s The Man Who Copied Children’s Classics Matinees City of God Mary Poppins Olga Babe Bus 174 The Great Muppet Caper Possible Loves The Lady and the Tramp Carandiru Wallace and Gromit in The Curse of the God is Brazilian Were-Rabbit Madam Satan Hans Staden The Overlooked Ford Central Station Up the River The Whole Town’s Talking Fosse Pilgrimage Kiss Me Kate Judge Priest / The Sun Shines Bright The A!airs of Dobie Gillis The Fugitive White Christmas Wagon Master My Sister Eileen The Wings of Eagles The Pajama Game Cheyenne Autumn How to Succeed in Business Without Really Seven Women Trying Sweet Charity Labor, Globalization, and the New Econ- Cabaret omy: Recent Films The Little Prince Bread and Roses All That Jazz The Corporation Enron: The Smartest Guys in the Room Shaolin Chop Sockey!! Human Resources Enter the Dragon Life and Debt Shaolin Temple The Take Blazing Temple Blind Shaft The 36th Chamber of Shaolin The Devil’s Miner / The Yes Men Shao Lin Tzu Darwin’s Nightmare Martial Arts of Shaolin Iron Monkey Erich von Stroheim Fong Sai Yuk The Unbeliever Shaolin Soccer Blind Husbands Shaolin vs. Evil Dead Foolish Wives Merry-Go-Round Fall 2005 Greed The Merry Widow From the Trenches: The Everyday Soldier The Wedding March All Quiet on the Western Front The Great Gabbo Fires on the Plain (Nobi) Queen Kelly The Big Red One: The Reconstruction Five Graves to Cairo Das Boot Taegukgi Hwinalrmyeo: The Brotherhood of War Platoon Jean-Luc Godard (JLG): The Early Films, -

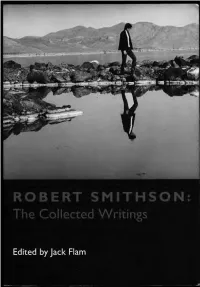

Collected Writings

THE DOCUMENTS O F TWENTIETH CENTURY ART General Editor, Jack Flam Founding Editor, Robert Motherwell Other titl es in the series available from University of California Press: Flight Out of Tillie: A Dada Diary by Hugo Ball John Elderfield Art as Art: The Selected Writings of Ad Reinhardt Barbara Rose Memo irs of a Dada Dnnnmer by Richard Huelsenbeck Hans J. Kl ein sc hmidt German Expressionism: Dowments jro111 the End of th e Wilhelmine Empire to th e Rise of National Socialis111 Rose-Carol Washton Long Matisse on Art, Revised Edition Jack Flam Pop Art: A Critical History Steven Henry Madoff Co llected Writings of Robert Mothen/le/1 Stephanie Terenzio Conversations with Cezanne Michael Doran ROBERT SMITHSON: THE COLLECTED WRITINGS EDITED BY JACK FLAM UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA PRESS Berkeley Los Angeles Londo n University of Cali fornia Press Berkeley and Los Angeles, California University of California Press, Ltd. London, England © 1996 by the Estate of Robert Smithson Introduction © 1996 by Jack Flam Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Smithson, Robert. Robert Smithson, the collected writings I edited, with an Introduction by Jack Flam. p. em.- (The documents of twentieth century art) Originally published: The writings of Robert Smithson. New York: New York University Press, 1979. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 0-520-20385-2 (pbk.: alk. paper) r. Art. I. Title. II. Series. N7445.2.S62A3 5 1996 700-dc20 95-34773 C IP Printed in the United States of Am erica o8 07 o6 9 8 7 6 T he paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of ANSII NISO Z39·48-1992 (R 1997) (Per111anmce of Paper) . -

Sophie's World

Sophie’s World Jostien Gaarder Reviews: More praise for the international bestseller that has become “Europe’s oddball literary sensation of the decade” (New York Newsday) “A page-turner.” —Entertainment Weekly “First, think of a beginner’s guide to philosophy, written by a schoolteacher ... Next, imagine a fantasy novel— something like a modern-day version of Through the Looking Glass. Meld these disparate genres, and what do you get? Well, what you get is an improbable international bestseller ... a runaway hit... [a] tour deforce.” —Time “Compelling.” —Los Angeles Times “Its depth of learning, its intelligence and its totally original conception give it enormous magnetic appeal ... To be fully human, and to feel our continuity with 3,000 years of philosophical inquiry, we need to put ourselves in Sophie’s world.” —Boston Sunday Globe “Involving and often humorous.” —USA Today “In the adroit hands of Jostein Gaarder, the whole sweep of three millennia of Western philosophy is rendered as lively as a gossip column ... Literary sorcery of the first rank.” —Fort Worth Star-Telegram “A comprehensive history of Western philosophy as recounted to a 14-year-old Norwegian schoolgirl... The book will serve as a first-rate introduction to anyone who never took an introductory philosophy course, and as a pleasant refresher for those who have and have forgotten most of it... [Sophie’s mother] is a marvelous comic foil.” —Newsweek “Terrifically entertaining and imaginative ... I’ll read Sophie’s World again.” — Daily Mail “What is admirable in the novel is the utter unpretentious-ness of the philosophical lessons, the plain and workmanlike prose which manages to deliver Western philosophy in accounts that are crystal clear. -

Journey to Italy Press Notes

Janus Films Presents Roberto Rossellini’s Journey to Italy NEW DCP RESTORATION! http://www.janusfilms.com/journey Director: Roberto Rossellini JANUS FILMS Country: Italy Sarah Finklea Language: English Ph: 212-756-8715 Year: 1954 [email protected] Run time: 86 minutes B&W / 1.37 / Mono JOURNEY TO ITALY SYNOPSIS Among the most influential films of the postwar era, Roberto Rossellini’s Journey to Italy charts the declining marriage of a British couple (Ingrid Bergman and George Sanders) on a trip in the countryside near Naples. More than just an anatomy of a relationship, Rossellini’s masterpiece is a heartrending work of emotional transcendence and profound spirituality. Considered an ancestor of the existential works of Michelangelo Antonioni; hailed as a groundbreaking work of modernism by the critics of Cahiers du cinéma; and named by Martin Scorsese as one of his favorite films, Journey to Italy is a breathtaking cinematic landmark. Janus Films is proud to present a new, definitive restoration of the essential English-language version of the film, featuring Bergman and Sanders voicing their own dialogue. JOURNEY TO ITALY ABOUT THE ROSSELLINI PROJECT The Rossellini Project continues the initiative created by Luce Cinecittà, Cineteca di Bologna, CSC-Cineteca Nazionale, and the Coproduction Office as a means of rediscovering and showcasing the work of a reference point in the art of cinema: Roberto Rossellini. Three of Italian cinema’s great institutions and an influential international production house have joined forces to restore a central and fundamental part of the filmmaker’s filmography, as well as promote and distribute it on an international level. -

Entropy and Art: Essay on Disorder and Order

ENTROPY AND ART AN ESSAY ON DISORDER AND ORDER RUDOLF ARNHEIM ABSTRACT. Order is a necessary condition for anything the hu- man mind is to understand. Arrangements such as the layout of a city or building, a set of tools, a display of merchandise, the ver- bal exposition of facts or ideas, or a painting or piece of music are called orderly when an observer or listener can grasp their overall structure and the ramification of the structure in some detail. Or- der makes it possible to focus on what is alike and what is differ- ent, what belongs together and what is segregated. When noth- ing superfluous is included and nothing indispensable left out, one can understand the interrelation of the whole and its parts, as well as the hierarchic scale of importance and power by which some structural features are dominant, others subordinate. 2 RUDOLF ARNHEIM CONTENTS Part 1. 3 1. USEFUL ORDER 3 2. REFLECTIONS OF PHYSICAL ORDER 4 3. DISORDER AND DEGRADATION 7 4. WHAT THE PHYSICIST HAS IN MIND 11 5. INFORMATION AND ORDER 13 6. PROBABILITY AND STRUCTURE 17 7. EQUILIBRIUM 21 8. TENSION REDUCTION AND WEAR AND TEAR 22 9. THE VIRTUE OF CONSTRAINTS 25 10. THE STRUCTURAL THEME 27 Part 2. 32 11. ORDER IN THE SECOND PLACE 32 12. THE PLEASURES OF TENSION REDUCTION 35 13. HOMEOSTASIS IS NOT ENOUGH 39 14. A NEED FOR COMPLEXITY 40 15. ART MADE SIMPLE 43 16. CALL FOR STRUCTURE 46 References 48 ENTROPY AND ART AN ESSAY ON DISORDER AND ORDER 3 Part 1. -

Rossellini-Stromboli-2013

‘Modern Marriage on Stromboli,’ Essay on Roberto Rossellini’s Stromboli (1950), with Ingrid Bergman. Booklet to the Criterion Collection’s (New York) DVD of the film, September 2013 (http://www.criterion.com/current/posts/2908-modern-marriage-on- stromboli). 1 Modern Marriage on Stromboli By Dina Iordanova When I first saw Stromboli (1950) years ago, it resonated with me as no film had before, intensely and unswervingly—not least because I was identifying with Karin, the heroine, a woman cast out and traumatized, living in limbo and acting rashly to get herself out of that state. Seeing Stromboli now, after so many years, I am no less amazed by what Roberto Rossellini accomplished: the film is so direct and unforgiving, so absorbed with its flawed yet captivating protagonist . To me, the greatness of this film is that it does not seek to flatter. Rather, it tackles head-on the tribulations and the insolence that a woman may experience in the process of her emancipation. Faced with the consequences of her disquiet, Stromboli’s protagonist is one of those people who need to take action, even at the risk of getting into a still more convoluted situation than the one they seek to exit. She would rather be foolish but be a “doer”; she seeks to act rather than reflect, wait, or let go. **** It is just after World War II, at the height of personal and historical dislocation for thousands. So many fates have been shaken by the conflict. People have had to smuggle themselves across borders and live in camps, unable to plan and waiting for a new lease on life, perhaps somewhere as far away as Latin America.