The Princess Alice Disaster 1878

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

EDC/17/0123 Site Address: Northfleet Embankment East, Crete Hall Road

Agenda Item: 006 Reference: EDC/17/0123 Site Address: Northfleet Embankment East, Crete Hall Road, Northfleet. Proposal: Application for the variation of conditions 4, 5 and 19 attached to outline planning permission reference EDC/17/0022, for development of brownfield land to provide up to 21,500 sqm (231,000 sqft) of employment floorspace, comprising use classes B1, B2, B8 and A3, A4, A5 and associated site vehicular access, to amend the Building Heights Parameter Plan to allow the maximum height of buildings on part of the northern parcel to increase from 12 metres to 13.5 metres and to relocate the proposed pedestrian central refuge island crossing on Crete Hall Road. Applicant: Berkeley Modular Ltd Ward: Northfleet North SUMMARY: This application seeks amendments to the original outline planning permission to meet the requirements of a developer who has acquired part of the site (the Northern Parcel) and are seeking to develop it for a modular house building factory. The changes relate to a modest increase to the upper building height parameter to facilitate operational requirements and relocation of an approved pedestrian crossing island to better align it with the detailed layout. The proposed changes are considered to be acceptable in planning terms as they would not introduce any adverse impacts beyond those assessed and mitigated through the original outline permission. In particular the increase to the maximum building height from 12 metres to 13.5 metres should not materially alter the extent of visibility of the proposed development subject to appropriate design at the detailed stage. This has been verified by independent review of the EIA addendum submitted with the application, which satisfactorily concluded that the proposed changes do not introduce any new or different significant environmental effects over and above the original outline permission. -

John Bramwell Taylor Collection

John Bramwell Taylor Collection Monographs, Articles and Manuscripts 178B27 Photographs and Postcards 178C95 Correspondence 178F27 Notebooks 178P7 Handbills 178T1 Various 178Z42 178B27.1 Taylor of Ightham family tree Pen and ink document with multiple annotations 1p. John Bramwell Taylor Collection 178B27.2 Brookes Family Tree Pen document 1p. John Bramwell Taylor Collection 178C95.1 circa 100 black and white personal, family and holiday photographs John Bramwell Taylor Collection 178F27.1 1 box of letters John Bramwell Taylor Collection 178P7.1 4 notebooks containing hand written poems and other personal thoughts John Bramwell Taylor Collection Egyptian Hall - Piccadilly (see also 178T1.194 and 178T1.156) Ref: 178T1.1 Title: The Wild Man of the Prairies or "What is it"? Headline Act: Wild Man Location: Egyptian Hall - Piccadilly Show Type: Oddities/Curious Event Date: 1846 Folio: 4pp Item size: 127mm x 188mm Printed by: Francis, Printer, 25, Museum Street, Bloomsbury Other Information: Is it Human? Is it an animal? Is it an extraordinary freak of nature? Missing link between man and Ourang-Outang. Flyer details savage living habits, primarily eating fruit and nuts but occasionally must be given a meal of RAW MEAT. ‘Not entirely domesticated tho not averse to exhibition.’ See The Era (London, England), Sunday, August 30, 1846 1 Ref: 178T1.2 Title: Living Ourang Outans! Headline Act: Ourang Outans Location: Egyptian Hall - Piccadilly Show Type: Natural History/Animal Event Date: c1830s Folio: 1pp Item size: 185mm x 114mm Printed by: None given Other information: Male & Female Ourang Outans, One from Borneo - other from River Gambia. "Connecting link between man and the brute creation". -

DIRECT'ory·L ROSHERVILLE

DIRECT'ORy·l KENT. ROSHERVILLE. 461 Ashdown Edw8rd, saddler . Humphery John, superintendent regis- Paine Albert, -chemist ' Austen John Clement, camer, fish mer- trar &'clerk to guardians of Romney Pankhurst William, shoe maker , chant & seed grower Marsh union Pearson Richard, builder Baker Frederick. farmer & seed grower Hutchinson Alfred, land steward to Mrs. Rayner Henry, confectioner V" Bates Alfred. butcher' Bell ' Smith Alfred Henry, grocer Beard lsaac, shopkeeper Hutchinson Alfred, jun.carpenter' Smith Robert, stone ma!WII &; builder Boom William, baker Hmchinson Ann Eliza (Mrs.), Ship ~ Smith Mary (Mrs.), grazier Buss Thomas, farmer mercial 4- family hotel 4- posting lw. Southland's Ho.'I.pital (Rev. Richard Butler Thomas King, plumber agent to Hammond & Co. shipping Carolns Stevens, governor) Catt John, farm bailiff to H .. B. Walker agent, Dover & sub-agent to ~loyd's Standing Ebenezer, brick maker esq. .T.P . & wine & spirit merchant. Families Stonham & Son, millers Clark Christoph~r,grocer suppliedwith wine & spirits of choicest Stringer Henry, solicitor, town clerk. Cobb Frances (Mrs.), WaT1'en inn quality at wholesale prices registrar of county court, clerk to the Collyer Michael, beer retailer Hutchinson George, blacksmith highway board & notary pnblic Daglish Richard Rothwell, surgeon Jarrett Henry, Cinque Ports Arms Strond Matilda (Mrs.), clothier Daniel Henry Young, baker Jarrett Elizabeth (Mrs.), shopkeeper Tunbridge Thomas T. grazier Daniel John, baker Lingwood William, Ne'I(J inn Vidgen Elizabeth (Miss), ladies' -

The Dover Road

THE DOVER ROAD BY CHARLES G. HARPER The Dover Road I Of all the historic highways of England, the story of the old Road to Dover is the most difficult to tell. No other road in all Christendom (or Pagandom either, for that matter) has so long and continuous a history, nor one so crowded in every age with incident and associations. The writer, therefore, who has the telling of that story to accomplish is weighted with a heavy sense of responsibility, and though (like a village boy marching fearfully through a midnight churchyard) he whistles to keep his courage warm, yet, for all his outward show of indifference, he keeps an awed glance upon the shadows that beset his path, and is prepared to take to his heels at any moment. And see what portentous shadows crowd the long reaches of the Dover Road, and demand attention! Cæsar’s presence haunts the weird plateau of Barham Downs, and the alert imagination hears the tramp of the legionaries along Watling Street on moonlit nights. Shades of Britons, Saxons, Danes, and Normans people the streets of the old towns through which the highway takes its course, or crowd in warlike array upon the hillsides. Kings and queens, nobles, saints of different degrees of sanctity, great blackguards of every degree of blackguardism, and ecclesiastics holy, haughty, proud, or pitiful, rise up before one and terrify with thoughts of the space the record of their doings would occupy; in fine, the wraiths and phantoms of nigh upon two thousand years combine to intimidate the historian. -

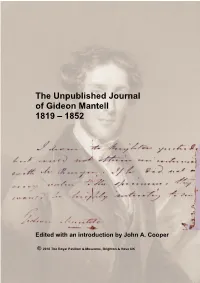

The Unpublished Journal of Gideon Mantell 1819 – 1852

The Unpublished Journal of Gideon Mantell 1819 – 1852 Edited with an introduction by John A. Cooper © 2010 The Royal Pavilion & Museums, Brighton & Hove UK 1 The Unpublished Journal of Gideon Mantell: 1819 – 1852 Introduction Historians of English society of the early 19th century, particularly those interested in the history of science, will be familiar with the journal of Gideon Algernon Mantell (1790-1852). Whilst not kept on a daily basis, Mantell’s journal, kept from 1818, offers valuable insights into not only his own remarkable life and work, but through his comments on a huge range of issues and personalities, contributes much to our understanding of contemporary science and society. Gideon Mantell died in 1852. All of his extensive archives passed first to his son Reginald and on his death, to his younger son Walter who in 1840 had emigrated to New Zealand. These papers together with Walter’s own library and papers were donated to the Alexander Turnbull Library in Wellington, New Zealand in 1927 by his daughter-in- law. At some time after that, a typescript was produced of the entire 4-volume manuscript journal and it is this typescript which has been the principal reference point for subsequent workers. In particular, an original copy was lodged with the Sussex Archaeological Society in Lewes, Sussex. In 1940, E. Cecil Curwen published his abridged version of Gideon Mantell’s Journal (Oxford University Press 1940) and his pencilled marks on the typescript indicate those portions of the text which he reproduced. About half of the text was published by Curwen. -

Agenda Reports Pack (Public) 05/10/2011, 19.00

Public Document Pack Regulatory Board Members of the Regulatory Board of Gravesham Borough Council are summoned to attend a meeting to be held at the Civic Centre, Windmill Street, Gravesend, Kent on Wednesday, 5 October 2011 at 7.00 pm when the business specified in the following agenda is proposed to be transacted. S Kilkie Assistant Director (Communities) Agenda Part A Items likely to be considered in Public 1. Apologies for absence 2. To sign the Minutes of the previous meeting (Pages 1 - 4) 3. To declare any interests members may have in the items contained on this agenda. When declaring an interest, members should state what their interest is. 4. To consider whether any items in Part A of the Agenda should be considered in private or the items in Part B (if any) in Public 5. Planning applications for determination by the Board The plans and originals of all representations are available for inspection in during normal office hours and in the committee room for a period of one hour before commencement of the meeting. a) GR/2011/0553 - 1 Downs Road, Istead Rise, Northfleet, Kent - (Pages 5 - 12) report herewith. b) GR/20110320 - Northfleet Embankment East, Northfleet, Kent - (Pages 13 - 56) report herewith. Civic Centre, Windmill Street, Gravesend Kent DA12 1AU 6. Planning applications determined under delegated powers by the Director (Business) A copy of the schedule has been placed in the democracy web library. http://www.gravesham.gov.uk/democracy/ecCatDisplay.aspx?sch=doc&c at=13418&path=480,12911 7. Any other business which by reason of special circumstances the Chair is of the opinion should be considered as a matter of urgency. -

A Canterbury Pilgrimage;

J'Biqiq iaq:jnos '^;tsj9atu III jiiwH' iriwi rniimfiiMiiWiiiniWIplWiflfmi ^ Hontion ? Pub!isf)et! bp ^eetej ants Compan?, riui. rlDii. anti xMil &^tx Street. ^^nccclrrrD, THE LIBRARY OF THE UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA LOS ANGELES / 2i Canteriiirp pilgrimage 77>/V work is Copyright in England and America. 91 €nnttvi)nvp ttiritten, anti illustrateH tip Josepb anD (ZBIi^abetJ) Lontion ; IputJlisfjen tip ^eelep ant) Company, ritji. rltiii. anD rltJiiL €0.ser Street. a^Dccclrrru* TO jlr. Kol)ert Xouis S»tebenson, IVe^ who are unknown to him^ dedicate this record of one of our short journeys on a Tricycle^ in gratitude fcr the happy hours we have spent travelling with him and his Donkey. Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2007 with funding from IVIicrosoft Corporation http://www.archive.org/details/canterburypilgriOOpenniala WE do not think our book needs an apology, explanation, or preface; nor does It seem to us worth while to give our route-form, since the road from London to Canterbury is almost as well known to cyclers as the Strand, or the Lancaster Pike ; nor to record our time, since we were pil- grims and not scorchers. And as for non-cyclers, who as yet know nothing of time and roads, we would rather show them how pleasant it is to go on pilgrimage than weary them with cycling fa(5ts. Joseph Pennell. Elizabeth Robins Pennell. 36 Bedford Place, May i^i/ij 1885. first Dap folk lio p on pilpimaffe tljrouff^ Ikent. CANTERBURY PILGRIMAGE towards the end of '^Y was August, when a hot sun was softening the asphalt in the dusty streets of London, and ripening the hops in the pleasant and of Kent, that we went on pilgrimage to Canterbury. -

Design Guidance for a Characterful and Distinctive Ebbsfleet Garden City

Design for Ebbsfleet Design guidance for a characterful and distinctive Ebbsfleet Garden City Ebbsfleet Development Corporation 1 Design for Ebbsfleet Welcome to the ‘Design for Ebbsfleet’ Design Guide The guide has been developed to help design teams develop characterful and distinctive homes and streets informed by the landscape and cultural heritage of the local area. This guidance document is specifcally focused on improving character, and should be used in conjunction with other appropriate national and local design guidance. Design teams are encouraged to... Cover image: University Library Bern, MUE Ryh 1806 : 22 2 Design for Ebbsfleet 1. Find out how to use 2. Review the analysis and gain 3. Explore Ebbsfleet’s design the guidance an understanding of Ebbsfleet’s narratives cultural landscapes 1.1 Introduction to Ebbsfleet Garden City 4 2.1 Introduction to the analysis 10 3.1 Narrative : Introduction to the design narratives 3.1.1 Relationship to the Ebbsfleet Implementation 38 1.2 How to use the guidance 5 2.2 Analysis : Learning from the landscape 3.1.2 Framework 39 2.2.1 Place names and the landscape palimpsest 10 1.3 How does the guidance relate to planning policy? 6 2.2.2 Geology 11 3.2 Narrative : ‘The Coombe’ 2.2.3 Landscape features, river to marsh to chalk cliffs 12 3.2.1 ‘The Pent’, ‘The Pinch’ & ‘The Scarp’ urban form 41 3.2.2 ‘The Pent’ urban form 42 2.3 Analysis : Learning from local villages 3.2.3 ‘The Pent’ architectural language 43 2.3.1 Cliffe 13 3.2.4 ‘The Pent’ references from the analysis 44 2.3.2 Farningham -

Trades Directory.] Kent

• TRADES DIRECTORY.] KENT. PUB 1055 J"ackson John Howard, 144 High street, Gravesend Public Hall Co. Limited Factory Club & Hall (W. T. Symons, Chatham & 42 High street, Rochester (Theophilus Smith, sec.), New road, sec.), High street, Northfleet ~.0 J"acobs Jas. Alfred, Marketst. Sandwich Gravesend Folkestone Lecture Hall (John Surrey, Kingsnorth William, 51 Strand, Lower 1Headcorn Hall Co. Limited (Thomas W. proprietor), Grace hill, Folkestone Walmer, Deal 1 Burden, sec.), Headcorn, Ashford Folkestone Town Hall, Guildhall street, Lane George, 12-1- Eastgate, Rochester Berne Bay Pavilion Promenade & Pier Folkestone Laurence Wm.28 High st.; 24 Low.Stone Co. Limited (Henry C. Jones, sec.), Foresters' Hall (John Gammon, hall street & :Market buildings, Maidstone 6o William street, Berne Bay S.O keeper), Chapel Place alley, Ramsgate Lee Abraham & Son, 33 Underdown Incorporated Co. of Oyster Dredgers Foresters' Halt (!<'.C. F.>rrester, sec.), street, Herne Bay S.O (Thomas Kemp, jun. foreman, John High street, Canterbury Martin Arthur, 41 King st. Ramsgate Thomas Reeves, treasurer; Plummer Foresters' Hall (Wm. E. Robinson, sec.), Mason John Adlington, 62 Windmill st. & Fielding, stewards; Absalom An- North Barrack rd. Lower Walmer,Deal Gravesend; 21 Gabriels hill, Maid- derson, clerk), Whitstable Foresters' Hall (John T. Reeves, sec.), stone & Clare ter. Sidcup hill, Sidcup Maidstone Cottage ImprOl·ement Co. Oxford street, Whitstable MillenThos.Wm.Postoff.Ch'ipstd.Sevnks Limited (George Hulburd, managing Foresters' Hall (William Hood, keeper). Moody Wm. J. 14 Trinity sq. Margate director; King & Hughes, solicitors) ; Raglan street, Forest Hill s E Moore Robert, Mortimer street & 7 registered office, 6 Mill st. Maidstone Freemasons' Hall, Brewer st. -

Agenda Item 005 Officer Report

Agenda Item: 005 Reference: EDC/17/0022 Site Address: Northfleet Embankment East, Crete Hall Road, Northfleet. Proposal: Outline application with all matters reserved except access for development of brownfield land to provide up to 21,500 m2 (231,000 ft2) of employment floorspace, comprising use classes B1, B2, B8 and A3, A4, A5 and associated site vehicular access. Applicant: Ebbsfleet Development Corporation Parish / Ward: Non-Parish Area SUMMARY: This outline application proposes a significant quantum of new employment floorspace on a previously developed industrial site on the south bank of the River Thames, within an area known as Northfleet Embankment East. The site is allocated in the Local Plan Core Strategy for employment led redevelopment. This site also comprises part of the Strategic Northfleet Riverside Development Area identified in the EDC’s Implementation Framework which seeks to develop new employment activities within the identified enterprise zone. The proposed development, in addition to being acceptable in planning policy terms, accords with EDC’s Implementation Framework that seeks to facilitate the establishment and growth of new and existing businesses providing a mix of sustainable jobs accessible to local people that puts Ebbsfleet on the map as a successful business location. It would also stimulate and act as a catalyst for inward investment to enhance the local economy to take advantage of the site’s location within the recently enacted North Kent Enterprise Zone and would make efficient use of a vacant previously -

Gardens and Gardening in a Fast-Changing Urban Environment

Gardens and Gardening in a fast-changing urban environment: Manchester 1750-1850 A Thesis submitted to Manchester Metropolitan University for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Joy Margaret Uings April 2013 MIRIAD, Manchester Metropolitan University List of Contents Abstract i Acknowledgments ii Tables, maps and images iv The Growth of Manchester and its suburbs 1750-1850 1 Introduction 3 Literature Review 11 History of Manchester 11 Class and Gender 15 Garden Design 22 Horticulture, Floriculture and Nurseries 28 Methodology 35 Chapter One: Horticultural Trade 45 Gardeners and nurserymen 46 Seedsmen and florists 48 Fruiterers and confectioners 51 Manchester and the North-west 52 1750-1790 53 1790-1830 57 1830-1850 61 Post 1850 71 Connections 73 Summary 77 Chapter Two: Plants 79 Forest trees 79 Fruit trees 89 Evergreen and flowering shrubs 97 Florist’s flowers 99 Exotic (hothouse) plants 107 Hardy plants 109 Vegetables 110 Agricultural Seeds 112 The fascination with unusual plants 114 The effect of weather on plants 117 Plant thefts 120 Summary 125 Chapter Three: Environmental Changes 127 Development of the town 128 Development of the suburbs 135 Smoke pollution 145 Summary 154 Chapter Four: Private Gardens 157 Garden design and composition 160 Garden designers 168 Urban gardens 171 Country gardens 179 Suburban gardens 185 Cottage gardens 195 Allotments 198 Summary 202 Chapter Five: Public Gardens 205 Gardens for refreshment 206 Gardens for pleasure 211 Gardens for activity 223 Gardens for education 230 Summary 243 Chapter Six: Public Spaces 245 Public footpaths – the ancient right of way 246 Whit week 254 Manchester’s public parks 256 Summary 275 Chapter Seven: The Element of Competition 277 Florist’s feasts 279 Horticultural shows 286 Gooseberry Shows 300 Summary 307 Conclusion 309 Horticultural Trade 309 Plants 311 Environmental Changes 313 Private Gardens 313 Public Gardens 314 Public Spaces 315 The Element of Competition 316 Summary 316 Appendix One: More Horticultural Tradesmen 318 Appendix Two: Robert Turner’s stock 342 Appendix Three: R. -

Handbills 178T

Handbills 178T 178T1- John Bramwell Taylor Collection 178T2-Circus Modern 178T3-Fairs Early 178T4-Steam Fairs (including Harry Lee) 178T5-Wall of Death (including Billy Bellhouse and Alma Skinner Collections) 178T6-Circus (early travelling and permanent) 178T7- George Dawson Collection 178T8-Shufflebottom Family Collection 178T9-Hamilton Kaye Collection 178T10-Fairs (modern, including David Fitzroy Collection) 178T11-Rail Excursions 178T12-New Variety and Theatre 178T13-Marisa Carnesky Collection 178T14-Variety and Music Hall 178T15-Pleasure Gardens 178T16-Waxworks (travelling and fixed) 178T17-Early Film and Cinema (travelling and fixed) 178T18- Travelling entertainments 178T19-Optical shows (travelling and fixed) 178T20-Panoramas (travelling and fixed) 178T21-Menageries/performing animals (travelling and fixed) 178T22-Oddities and Curios (travelling and fixed) 178T23- Fixed entertainment venues 178T24-Wild West 178T25-Boxing 178T26-Lulu Adams Collection 178T27-Cyril Critchlow Collection –see separate finding aid 178T28- Magic and Illusion 178T29 – Hal Denver Collection 178T30 – Charles Taylor Collection 178T31-Fred Holmes Collection (Jasper Redfern) 178T32-Hodson Family Collection 178T33-Gerry Cottle Collection 178T34 - Ben Jackson Collection 178T35 – Family La Bonche Project Collection 178T36 – Paul Braithwaite Collection 178T37 – Chris Russell Collection 178T38 – Exhibitions 178T39 – David Robinson (Not yet available) 178T40 – Circus Friends Association Collection (Not yet available) 178T41 – O’Beirne Collection 178T42 – Smart Family