Michael Wong Oral History Interview and Transcript

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Download the Press Kit Here

SSFL PK.V1 – 2016 OCT 1 OF 34 JASMINE A SHANGHAI STREET FILMS PRODUCTION PRODUCED, WRITTEN, & DIRECTED BY DAX PHELAN STARRING JASON TOBIN, EUGENIA YUAN, GLEN CHIN, SARAH LIAN, & BYRON MANN PRODUCED BY STRATTON LEOPOLD, ERIC M. KLEIN, JASON TOBIN, JENNIFER THYM, CHRIS CHAN LEE, MARTIN STRACHAN, GUY LIVNEH PRESS KIT – OCTOBER 17 , 2016 (ver. 1) SSFL PK.V1 – 2016 OCT 2 OF 34 TAGLINE He loved her. LOGLINE JASMINE is a mind-bending psychologicAl thriller About A mAn who’s struggling to come to terms with his grief neArly A yeAr After his wife’s unsolved murder. SHORT SYNOPSIS JASMINE is a mind-bending psychologicAl thriller About A mAn, LeonArd To (JAson Tobin), who’s struggling to come to terms with his grief neArly A yeAr After his wife’s unsolved murder. Hoping to move on with his life, LeonArd reconnects with GrAce (Eugenia YuAn), A womAn from his pAst, And his outlook begins to brighten. But, when A visit to the site of his wife’s murder leAds him to A mysterious interloper (Byron MAnn) who he believes is her killer, LeonArd decides to tAke justice into his own hands And things tAke A stArtling turn towArd the unexpected. LONG SYNOPSIS LeonArd To (JAson Tobin, “Better Luck Tomorrow”) is A mAn who’s struggling to come to terms with the unsolved murder of his beloved wife, JAsmine (GrAce Huang, “OverheArd,” “Cold WAr,” “The MAn With The Iron Fists”). NeArly A yeAr After JAsmine’s deAth, LeonArd returns home to Hong Kong, determined to move on with his life once And for All. -

Va.Orgjackie's MOVIES

Va.orgJACKIE'S MOVIES Jackie starred in his first movie at the age of eight and has been making movies ever since. Here's a list of Jackie's films: These are the films Jackie made as a child: ·Big and Little Wong Tin-Bar (1962) · The Lover Eternal (1963) · The Story of Qui Xiang Lin (1964) · Come Drink with Me (1966) · A Touch of Zen (1968) These are films where Jackie was a stuntman only: Fist of Fury (1971) Enter the Dragon (1973) The Himalayan (1975) Fantasy Mission Force (1982) Here is the complete list of all the rest of Jackie's movies: ·The Little Tiger of Canton (1971, also: Master with Cracked Fingers) · CAST : Jackie Chan (aka Chen Yuen Lung), Juan Hsao Ten, Shih Tien, Han Kyo Tsi · DIRECTOR : Chin Hsin · STUNT COORDINATOR : Chan Yuen Long, Se Fu Tsai · PRODUCER : Li Long Koon · The Heroine (1971, also: Kung Fu Girl) · CAST : Jackie Chan (aka Chen Yuen Lung), Cheng Pei-pei, James Tien, Jo Shishido · DIRECTOR : Lo Wei · STUNT COORDINATOR : Jackie Chan · Not Scared to Die (1973, also: Eagle's Shadow Fist) · CAST : Wang Qing, Lin Xiu, Jackie Chan (aka Chen Yuen Lung) · DIRECTOR : Zhu Wu · PRODUCER : Hoi Ling · WRITER : Su Lan · STUNT COORDINATOR : Jackie Chan · All in the Family (1975) · CAST : Linda Chu, Dean Shek, Samo Hung, Jackie Chan · DIRECTOR : Chan Mu · PRODUCER : Raymond Chow · WRITER : Ken Suma · Hand of Death (1976, also: Countdown in Kung Fu) · CAST : Dorian Tan, James Tien, Jackie Chan · DIRECTOR : John Woo · WRITER : John Woo · STUNT COORDINATOR : Samo Hung · New Fist of Fury (1976) · CAST : Jackie Chan, Nora Miao, Lo Wei, Han Ying Chieh, Chen King, Chan Sing · DIRECTOR : Lo Wei · STUNT COORDINATOR : Han Ying Chieh · Shaolin Wooden Men (1976) · CAST : Jackie Chan, Kam Kan, Simon Yuen, Lung Chung-erh · DIRECTOR : Lo Wei · WRITER : Chen Chi-hwa · STUNT COORDINATOR : Li Ming-wen, Jackie Chan · Killer Meteors (1977, also: Jackie Chan vs. -

A Different Brilliance—The D & B Story

1. Yes, Madam (1985): Michelle Yeoh 2. Love Unto Wastes (1986): (left) Elaine Jin; (right) Tony Leung Chiu-wai 3. An Autumn’s Tale (1987): (left) Chow Yun-fat; (right) Cherie Chung 4. Where’s Officer Tuba? (1986): Sammo Hung 5. Hong Kong 1941 (1984): (from left) Alex Man, Cecilia Yip, Chow Yun-fat 6. It’s a Mad, Mad, Mad World (1987): (front row from left) Loletta Lee, Elsie Chan, Pauline Kwan, Lydia Sum, Bill Tung; (back row) John Chiang 7. The Return of Pom Pom (1984): (left) John Sham; (right) Richard Ng 8. Heart to Hearts (1988): (from left) Dodo Cheng, George Lam, Vivian Chow Pic. 1-8 © 2010 Fortune Star Media Limited All Rights Reserved Contents 4 Foreword Kwok Ching-ling, Wong Ha-pak 〈Chapter I〉 Production • Cinema Circuits 10 D & B’s Development: From Production Company to Theatrical Distribution Po Fung Circuit 19 Retrospective on the Big Three: Dickson Poon and the Rise-and-Fall Story of the Wong Ha-pak D & B Cinema Circuit 29 An Unconventional Filmmaker—John Sham Eric Tsang Siu-wang 36 My Days at D & B Shu Kei In-Depth Portraits 46 John Sham Diversification Strategies of a Resolute Producer 54 Stephen Shin Targeting the Middle-Class Audience Demographic 61 Linda Kuk An Administrative Producer Who Embodies Both Strength and Gentleness 67 Norman Chan A Production Controller Who Changes the Game 73 Terence Chang Bringing Hong Kong Films to the International Stage 78 Otto Leong Cinema Circuit Management: Flexibility Is the Way to Go 〈Chapter II〉 Creative Minds 86 D & B: The Creative Trajectory of a Trailblazer Thomas Shin 92 From -

Shaw Brothers Films List

The Shaw Brothers Collection of Films on DVD Distributed by Celestial Pictures Collection 23 Titles grouped by year of original theatrical release (Request titles by ARSC Study Copy No.) ARSC Study Film Id English Title Chinese Title Director Genre Year Casts Copy No. Lin Dai 林黛, Chao Lei 趙雷, Yang Chi-ching 楊志卿, Lo Wei 1 DVD5517 M 156012 Diau Charn 貂蟬 Li Han-hsiang 李翰祥 Huangmei Opera 1956 羅維 DVD5518 M 1.1 (Karaoke Diau Charn 貂蟬 disc) Lin Dai 林黛, Chao Lei 趙雷, Chin Chuan 金銓, Yang Chi- 2 DVD5329 M 158005 Kingdom And The Beauty, The 江山美人 Li Han-hsiang 李翰祥 Huangmei Opera 1958 ching 楊志卿, Wong Yuen-loong 王元龍 Enchanting Shadow Lo Tih 樂蒂, Chao Lei 趙雷, Yang Chi-ching 楊志卿, Lo Chi 3 DVD5305 M 159005 倩女幽魂 Li Han-hsiang 李翰祥 Horror 1959 洛奇 Rear Entrance Butterfly Woo 胡蝶, Li Hsiang-chun 李香君, Chao Ming 趙明, 4 DVD5149 M 159016 後門 Li Han-hsiang 李翰祥 Drama 1959 (B/W) Chin Miao 井淼, Wang Ai-ming 王愛明, Wang Yin 王引 Lin Dai 林黛, Chao Lei 趙雷, Hung Por 洪波,Wang Yueh-ting 5 DVD5212 M 159021 Beyond The Great Wall 王昭君 Li Han-hsiang 李翰祥 Huangmei Opera 1959 王月汀, Chang Tsui-yin 張翠英, Li Yin 李英 Lin Dai 林黛, Chen Ho 陳厚, Fanny Fan 范麗, Kao Pao-shu 6 DVD5209 M 160004 Les Belles 千嬌百媚 Doe Chin 陶秦 Musical 1960 高寶樹, Mak Kay 麥基 7 DVD5433 M 160006 Magnificent Concubine, The 楊貴妃 Li Han-hsiang 李翰祥 Huangmei Opera 1960 Li Li-hua 李麗華, Yen Chuan 嚴俊, Li Hsiang-chun 李香君 Li Li-hua 李麗華, Chao Lei 趙雷, Chiao Chuang 喬莊, Lo Chi 8 DVD5452 M 160011 Empress Wu 武則天 Li Han-hsiang 李翰祥 Period Drama 1960 洛奇, Yu Feng-chi 俞鳳至 Loh Tih 樂蒂, Diana Chang Chung-wen 張仲文, Ting Ning 9 DVD5317 M 160020 Bride Napping, The -

Police Vs Syndicats Du Crime

Arnaud Lanuque POLICE VS SYNDICATS DU CRIME Les polars et films de triades dans le cinéma de Hong Kong ISBN 9 979-10-91328-16-6 © Éditions GOPE, 435 route de Crédoz, 74930 Scientrier, mai 2017 Relecture, correction : David Magliocco, Marie Armelle Terrien-Biotteau Couverture : David Magliocco Illustration couverture : © Yannick « Drelium » Langevin Le code de la propriété intellectuelle interdit les copies ou reproductions destinées à une utilisation collective. Toute représentation ou reproduction intégrale ou partielle faite par quelque procédé que ce soit, sans le consentement de l’auteur ou de ses ayants cause, est illicite et constitue une contrefaçon sanctionnée par les articles L335-2 et suivants du Code de la propriété intellectuelle. PRÉFACE PAR LAWRENCE AH MON -------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- Préface par Lawrence Ah Mon Mentionnez Hong Kong à quelqu’un, où que ce soit dans le monde, et il y a de fortes probabilités que deux choses lui viennent naturellement à l’esprit : Bruce Lee et le kung-fu. En tant que phénomène culturel ou social, les films d’arts martiaux ont déjà fait l’objet de nombreuses pu- blications. Il est temps qu’un œil critique soit tourné vers un autre genre aussi vital qu’indispensable du cinéma de Hong Kong : les films consa- crés à la police et à sa némésis, les triades. L’ouvrage d’Arnaud Lanuque sur le sujet ne pouvait pas arriver à un meilleur moment car, avec l’industrie cinématographique hongkon- gaise de plus en plus à la merci des investisseurs de Chine continentale, toute description un tant soit peu réaliste des actions du milieu est de plus en plus difficile à montrer, voire purement et simplement censurée. -

Fewer Chinese Tourists

October 2019 | Vol. 49 | Issue 10 THE AMERICAN CHAMBER OF COMMERCE IN TAIPEI IN OF COMMERCE THE AMERICAN CHAMBER TAIWAN BUSINESS TOPICS TAIWAN Fewer Chinese Tourists: What will be the Impact? 來台陸客萎縮 衝擊知多少? October 2019 | Vol. 49 | Issue 10 Vol. October 2019 | INDUSTRY FOCUS 中 華 郵 政 北 台 字 第 ENVIRONMENT BACKGROUNDER 5000 MAKING TAIWAN BILINGUAL 號 執 照 登 記 為 雜 誌 交 寄 ISSUE SPONSOR Published by the American Chamber Of NT$150 Commerce In Taipei Read TOPICS Online at topics.amcham.com.tw 10_2019_Cover.indd 1 2019/10/3 下午9:59 CONTENTS NEWS AND VIEWS 6 Editorial Promoting the Exchange of Talent OCTOBER 2019 VOLUME 49, NUMBER 10 推動美台人才交流 一○八年十月號 7 President’s View A bruising keynote speech high- Publisher lights one of AmCham’s vital roles William Foreman Editor-in-Chief By William Foreman Don Shapiro 8 Taiwan Briefs Deputy Editor Jeremy Olivier By Jeremy Olivier Art Director/ / 13 Issues Production Coordinator Katia Chen New Era for Cosmetics Regulation; Manager, Publications Sales & Marketing Regulating Dispatch Labor; Good- Caroline Lee bye Saturday Securities Trading Translation Kevin Chen, Yichun Chen, Charlize Hung 化粧品法規新時代;派遣勞工規範; 跟週六證券交易說掰掰 By Anna Yang and Niralee Shah American Chamber of Commerce in Taipei 129 MinSheng East Road, Section 3, 7F, Suite 706, Taipei 10596, Taiwan COVER SECTION P.O. Box 17-277, Taipei, 10419 Taiwan Tel: 2718-8226 Fax: 2718-8182 By Mathew Fulco 撰文/傅長壽 e-mail: [email protected] website: http://www.amcham.com.tw 18 Fewer Chinese Tourists: What will be the Impact? 050 2718-8226 2718-8182 來台陸客萎縮 衝擊知多少? Taiwan Business Topics is a publication of the American Chamber of Commerce in Taipei, ROC. -

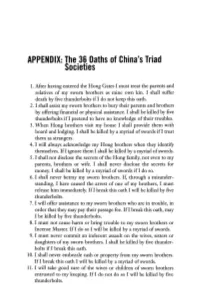

APPENDIX: the 36 Oaths of China's Triad Societies

APPENDIX: The 36 Oaths of China's Triad Societies 1. Mter having entered the Hong Gates I must treat the parents and relatives of my sworn brothers as mine own kin. I shall suffer death by five thunderbolts if I do not keep this oath. 2. I shall assist my sworn brothers to bury their parents and brothers by offering financial or physical assistance. I shall be killed by five thunderbolts if I pretend to have no knowledge of their troubles. 3. When Hong brothers visit my house I shall provide them with board and lodging. I shall be killed by a myriad of swords if I treat them as strangers. 4. I will always acknowledge my Hong brothers when they identify themselves. If I ignore them I shall be killed by a myriad of swords. 5. I shall not disclose the secrets of the Hong family, not even to my parents, brothers or wife. I shall never disclose the secrets for money. I shall be killed by a myriad of swords if I do so. 6. I shall never betray my sworn brothers. If, through a misunder standing, I have caused the arrest of one of my brothers, I must release him immediately. If I break this oath I will be killed by five thunderbolts. 7. I will offer assistance to my sworn brothers who are in trouble, in order that they may pay their passage fee. If I break this oath, may I be killed by five thunderbolts. 8. I must not cause harm or bring trouble to my sworn brothers or Incense Master. -

The Warrior Women of Transnational Cinema: Gender and Race in Hollywood and Hong Kong Action Movies

Wilfrid Laurier University Scholars Commons @ Laurier Theses and Dissertations (Comprehensive) 2010 The Warrior Women of Transnational Cinema: Gender and Race in Hollywood and Hong Kong Action Movies Lisa Funnell Wilfrid Laurier University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholars.wlu.ca/etd Part of the Film and Media Studies Commons, Race, Ethnicity and Post-Colonial Studies Commons, and the Women's Studies Commons Recommended Citation Funnell, Lisa, "The Warrior Women of Transnational Cinema: Gender and Race in Hollywood and Hong Kong Action Movies" (2010). Theses and Dissertations (Comprehensive). 1091. https://scholars.wlu.ca/etd/1091 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by Scholars Commons @ Laurier. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations (Comprehensive) by an authorized administrator of Scholars Commons @ Laurier. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Library and Archives Bibliotheque et 1*1 Canada Archives Canada Published Heritage Direction du Branch Patrimoine de I'edition 395 Wellington Street 395, rue Wellington Ottawa ON K1A 0N4 Ottawa ON K1A 0N4 Canada Canada Your file Votre reference ISBN: 978-0-494-64398-3 Our file Notre r§f6rence ISBN: 978-0-494-64398-3 NOTICE: AVIS: The author has granted a non L'auteur a accorde une licence non exclusive exclusive license allowing Library and permettant a la Bibliotheque et Archives Archives Canada to reproduce, Canada de reproduire, publier, archiver, publish, archive, preserve, conserve, sauvegarder, conserver, transmettre au public communicate to the public by par telecommunication ou par I'Internet, preter, telecommunication or on the Internet, distribuer et vendre des theses partout dans le loan, distribute and sell theses monde, a des fins commerciales ou autres, sur worldwide, for commercial or non support microforme, papier, electronique et/ou commercial purposes, in microform, autres formats. -

Chinese Community Health Care Association (CCHCA) Supports Self-Help for the Elderly to Strive for the Improvement of Seniors'

WINTER 2020 • VOL 27 ISSUE NO.2 二零二零年 冬季 • 第二十七冊 第二期 www.selfhelpelderly.org Chinese Community Health Care Association (CCHCA) Supports Self-Help for the Elderly to Strive for the Improvement of Seniors’ Health 華美醫師協會支持安老自助處 努力促進長者健康生活 P1 ,4-5 Dignity Health St. Mary’s Medical Center Awarded the Asian Health Collaborative to Address Critical Healthcare Needs in the Asian Community Dignity Health / 聖瑪利醫療中心 2020年社區健康補助金頒發《亞太裔健 康聯盟》改善亞裔社區健康急需 P6 Check Presentation (L-R): Mrs. Ya Ci Wu & Mr. Wo Pei Wu, Lady Shaw Housing Residents; Dr. Joseph Woo, Director of Community Relations of CCHCA; Dr. Mai-Sei Chan, Treasurer of CCHCA; Dr. Fred Lui, President Self-Help for the Elderly (SHE) of CCHCA; Anni Chung, President & CEO of Self-Help for the Elderly; and Alex Tan, Director of Nutrition and HOPE 2020 Virtual Gala Senior Centers at Self-Help for the Elderly 安老自助處二零二零年網上 《迎福長壽宴》 P8-10 We Have Completed 47,135 Miles Chinese Community Health Care to Walk, Run, Ride to the Moon 安老自助處雲端慈善健身活動 Association (CCHCA) Supports Self-Help — 步 行 、跑 步 、踏 單 車 往 月 球 》 完成 47,135英里 P12-13 for the Elderly to Strive for the Comcast & Self-Help for the Elderly’s Intergenerational Youth Leadership Improvement of Seniors’ Health & Technology Program Graduation Comcast及安老自助處《跨世代青少 年領袖及科技計劃》畢業典禮2020 Self-Help for the Elderly is honored At the virtual press conference, P14-15 Self-Help for the Elderly’s Annual to be a beneficiary of Chinese President of CCHCA, Dr. Fred Lui, Thanksgiving Luncheon Brings Community Health Care Association explained CCHCA’s mission to Love & Warmth to the Community 200 Volunteers Distributed and (CCHCA) and our work together to strive to support the improvement Delivered 3,000 Thanksgiving do good for the senior community and promotion of public health for Meal Kits to Seniors and Families with Children in the San Francisco Bay Area. -

Taiwan-Business-TOPICS-January

CONTENTS 6 American Soy and the Taiwanese Diet Soy products like beancurd and soy JANUARY 2016 VOLUME 46, NUMBER 1 一○五年一月號 milk are a big part of the local diet, and almost all of the soybeans used in their production are imported Publisher 發行人 from the United States. Andrea Wu 吳王小珍 By Steven Crook Editor-in-Chief 總編輯 Don Shapiro 沙蕩 Associate Editor 副主編 14 Taiwanese Cooking – By the Tim Ferry 法緹姆 Book Art Director/ 美術主任/ Using four English-language cook- Production Coordinator 後製統籌 books for guidance, a foreign 陳國梅 Katia Chen national learns to prepare Taiwanese Manager, Publications Sales & Marketing 廣告行銷經理 dishes in what turned out to be not Caroline Lee 李佳紋 just a culinary adventure, but a life lesson. photo: rich Matheson By Jules Quartly American Chamber of Commerce in Taipei 129 MinSheng East Road, Section 3, 7F, Suite 706, Taipei 10596, Taiwan P.O. Box 17-277, Taipei, 10419 Taiwan 18 Buffet Dining in Taipei Tel: 2718-8226 Fax: 2718-8182 e-mail: [email protected] Goes Upmarket website: http://www.amcham.com.tw Top hotels are rolling out elabo- 名稱:台北市美國商會工商雜誌 發行所:台北市美國商會 rate all-you-can eat spreads, gen- 臺北市10596民生東路三段129號七樓706室 erally with lots of fresh seafood, to 電話:2718-8226 傳真:2718-8182 the delight of diners. Taiwan Business TOPICS is a publication of the American Chamber of Commerce in Taipei, ROC. Contents are independent of and do not By Matthew Fulco necessarily reflect the views of the Officers, Board of Governors, Supervisors or members. © Copyright 2016 by the American Chamber of Commerce in Taipei, ROC.