Assessing the Representation of Live, Native, Terrestrial Mammalian Wildlife In

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Local Business Database Local Business Database: Alphabetical Listing

Local Business Database Local Business Database: Alphabetical Listing Business Name City State Category 111 Chop House Worcester MA Restaurants 122 Diner Holden MA Restaurants 1369 Coffee House Cambridge MA Coffee 180FitGym Springfield MA Sports and Recreation 202 Liquors Holyoke MA Beer, Wine and Spirits 21st Amendment Boston MA Restaurants 25 Central Northampton MA Retail 2nd Street Baking Co Turners Falls MA Food and Beverage 3A Cafe Plymouth MA Restaurants 4 Bros Bistro West Yarmouth MA Restaurants 4 Family Charlemont MA Travel & Transportation 5 and 10 Antique Gallery Deerfield MA Retail 5 Star Supermarket Springfield MA Supermarkets and Groceries 7 B's Bar and Grill Westfield MA Restaurants 7 Nana Japanese Steakhouse Worcester MA Restaurants 76 Discount Liquors Westfield MA Beer, Wine and Spirits 7a Foods West Tisbury MA Restaurants 7B's Bar and Grill Westfield MA Restaurants 7th Wave Restaurant Rockport MA Restaurants 9 Tastes Cambridge MA Restaurants 90 Main Eatery Charlemont MA Restaurants 90 Meat Outlet Springfield MA Food and Beverage 906 Homwin Chinese Restaurant Springfield MA Restaurants 99 Nail Salon Milford MA Beauty and Spa A Child's Garden Northampton MA Retail A Cut Above Florist Chicopee MA Florists A Heart for Art Shelburne Falls MA Retail A J Tomaiolo Italian Restaurant Northborough MA Restaurants A J's Apollos Market Mattapan MA Convenience Stores A New Face Skin Care & Body Work Montague MA Beauty and Spa A Notch Above Northampton MA Services and Supplies A Street Liquors Hull MA Beer, Wine and Spirits A Taste of Vietnam Leominster MA Pizza A Turning Point Turners Falls MA Beauty and Spa A Valley Antiques Northampton MA Retail A. -

1 a SHORT BIBLIOGRAPHY in ZOOSEMIOTICS Abram, David

A SHORT BIBLIOGRAPHY IN ZOOSEMIOTICS Abram, David 1997. The Spell of the Sensuous. New York: Random House. Abram, David 2010. Becoming Animal: An Earthly Cosmology. New York: Pantheon Books. Ackerman, Diane 1991. A Natural History of the Senses. New York: Vintage Books. Argyle, Michael 1988. Bodily Communication. New York: Methuen. Barbieri, Marcello 2003. The Organic Codes. An Introduction to Semantic Biology. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Bateson, Gregory 1972. Steps to an Ecology of Mind. New York: Ballantine. Bekoff, Marc 2007. The Emotional Lives of Animals. Novato, Canada: New World Library. Bekoff, Marc 2008. Animals at Play. Rules of the Game. Philadelphia: Temple University Press. Bekoff, Marc; Pierce, Jessica 2009. Wild Justice: The Moral Lives of Animals. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press. Böll, Mette Miriam Rakel 2008. Social is emotional. Biosemiotics 1: 329–345. Bouissac, Paul 2010. Semiotics at the Circus. Semiotics, Communication and Cognition 3. Berlin: Walter de Gruyter. Bradbury, Jack W.; Vehrencamp, Sandra L. 2011. Principles of Animal Communication, 2nd Ed. Sunderland: Sinauer. Brock, Friedrich 1939. Typenlehre und Umweltforschung: Grundlegung einer idealistischen Biologie (= Bios vol. 9). Leipzig: Verlag von Johann Ambrosium Barth. Buchanan, Brett 2008. Onto-ethologies: The Animal Environments of Uexküll, Heidegger, Merleau, and Deleuze. New York: SUNY Press. Burghardt, Gordon M. 2008. Updating von Uexküll: New directions in communication research. Journal of Comparative Psychology 122, 332–334. Carmeli, Yoram S. 2003. On human-to-animal communication: Biosemiotics and folk perceptions in zoos and circuses. Semiotica 146(3/4): 51–68. Chang, Han-liang 2003. Notes towards a semiotics of parasitism. Sign Systems Studies 31.2: 421–439. -

An Investigation Into the Welfare of Captive Polar Bears in Japan

______________________________________________________________________ AN INVESTIGATION INTO THE WELFARE OF CAPTIVE POLAR BEARS IN JAPAN ______________________________________________________________________ by the ANIMAL CONCERNS RESEARCH AND EDUCATION SOCIETY (ACRES). Published by Animal Concerns Research and Education Society (Acres) 2007. Written by: Amy Corrigan. Edited by: Rob Laidlaw, Louis Ng. Translations by: Nicholas Hirayama, Atsuchi Shoko. Wild polar bear photo : Lynn Rogers. The Animal Concerns Research and Education Society (Acres) is a Singaporean-based charity, founded in 2001 by Singaporeans. Acres aims to: • Foster respect and compassion for all animals. • Improve the living conditions and welfare of animals in captivity. • Educate people on lifestyle choices which do not involve the abuse of animals and which are environment-friendly. Our approach is Scientific, Creative, Practical and Positive . 30 Mandai Estate #05-06 Mandai Industrial Building Singapore 729918 Tel: +65 581 2488 Fax: +65 581 6318 www.acres.org.sg [email protected] www.acres.org.sg i AUTHORS AND EDITORS Amy Corrigan Amy Corrigan is the Director of Education and Research at the Animal Concerns Research and Education Society (Acres) and has a degree in Zoology from the University of Sheffield, specialising in animal behaviour. She has vast experience in the field of captive bear welfare, having worked with them for several years in a wildlife rescue centre. In 2005 she conducted a four-month investigation into the welfare of the polar bears at Singapore Zoo and subsequently wrote the report “What’s a polar bear doing in the tropics?” which was published by Acres in 2006. Rob Laidlaw Rob Laidlaw is a Chartered Biologist who began his involvement in animal protection work more than twenty-five years ago. -

2021 Santa Barbara Zoo Reciprocal List

2021 Santa Barbara Zoo Reciprocal List – Updated July 1, 2021 The following AZA-accredited institutions have agreed to offer a 50% discount on admission to visiting Santa Barbara Zoo Members who present a current membership card and valid picture ID at the entrance. Please note: Each participating zoo or aquarium may treat membership categories, parking fees, guest privileges, and additional benefits differently. Reciprocation policies subject to change without notice. Please call to confirm before you visit. Iowa Rosamond Gifford Zoo at Burnet Park - Syracuse Alabama Blank Park Zoo - Des Moines Seneca Park Zoo – Rochester Birmingham Zoo - Birmingham National Mississippi River Museum & Aquarium - Staten Island Zoo - Staten Island Alaska Dubuque Trevor Zoo - Millbrook Alaska SeaLife Center - Seaward Kansas Utica Zoo - Utica Arizona The David Traylor Zoo of Emporia - Emporia North Carolina Phoenix Zoo - Phoenix Hutchinson Zoo - Hutchinson Greensboro Science Center - Greensboro Reid Park Zoo - Tucson Lee Richardson Zoo - Garden Museum of Life and Science - Durham Sea Life Arizona Aquarium - Tempe City N.C. Aquarium at Fort Fisher - Kure Beach Arkansas Rolling Hills Zoo - Salina N.C. Aquarium at Pine Knoll Shores - Atlantic Beach Little Rock Zoo - Little Rock Sedgwick County Zoo - Wichita N.C. Aquarium on Roanoke Island - Manteo California Sunset Zoo - Manhattan Topeka North Carolina Zoological Park - Asheboro Aquarium of the Bay - San Francisco Zoological Park - Topeka Western N.C. (WNC) Nature Center – Asheville Cabrillo Marine Aquarium -

Zoo Research Guidelines Statistics for Typical Zoo Datasets

Zoo Research Guidelines Statistics for typical zoo datasets © British and Irish Association of Zoos and Aquariums 2006 All rights reserved. No part of this publication my be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording or any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. Plowman, A.B. (ed)(2006) Zoo Research Guidelines: Statistics for typical zoo datasets. BIAZA, London. First published 2006 Published and printed by: BIAZA Zoological Gardens, Regent’s Park, London NW1 4RY, United Kingdom ISSN 1479-5647 2 Zoo Research Guidelines: Statistics for typical zoo datasets Edited by Dr Amy Plowman Paignton Zoo Environmental Park, Totnes Road, Paignton, Devon TQ4 7EU, U.K. Contributing authors: Prof Graeme Ruxton Institute of Biomedical and Life Sciences, Graham Kerr Building, University of Glasgow, Glasgow G12 8QQ Dr Nick Colegrave Institute of Evolutionary Biology, School of Biological Sciences, University of Edinburgh, King's Buildings, West Mains Road, Edinburgh EH9 3JT Dr Juergen Engel Zoolution, Olchinger Str. 60, 82178 Puchheim, Germany. Dr Nicola Marples Department of Zoology, Trinity College, Dublin 2, Ireland. Dr Vicky Melfi Paignton Zoo Environmental Park, Totnes Road, Paignton, Devon TQ4 7EU, U.K. Dr Stephanie Wehnelt, Zoo Schmiding, Schmidingerstr. 5, A-4631 Krenglbach, Austria. Dr Sue Dow Bristol Zoo Gardens, Clifton, Bristol BS8 3HA, U.K. Dr Christine Caldwell Department of Psychology, University of Stirling, Stirling FK9 4LA, Scotland Dr Sheila Pankhurst Department of Life Sciences, Anglia Ruskin University, Cambridge CB1 1PT, U.K. Dr Hannah Buchanan-Smith Department of Psychology, University of Stirling, Stirling FK9 4LA, Scotland. -

![2020 Annual Report [July 1, 2019 – June 30, 2020]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/5732/2020-annual-report-july-1-2019-june-30-2020-485732.webp)

2020 Annual Report [July 1, 2019 – June 30, 2020]

Inspiring caring and action on behalf of wildlife and conservation FISCAL YEAR 2020 Annual Report [July 1, 2019 – June 30, 2020] Zoo New England | Fiscal Year 2020 Annual Report | 1 WHO WE ARE Zoo New England is the non-profit organization responsible for the operation of Franklin Park Zoo in Boston and Stone Zoo in Stoneham, Mass. Both are accredited by the Association of Zoos and Aquariums (AZA). Zoo New England’s mission is to inspire people to protect and sustain the natural world for future generations by creating fun and engaging experiences that integrate wildlife and conservation programs, research and education. To learn more about our Zoos, education programs and conservation efforts, please visit us at www.zoonewengland.org. Board of Directors Officers [FY 20: July 1, 2019 – June 30, 2020] David C. Porter, Board Chair Janice Houghton, Board Vice Chair Thomas Tinlin, Board Vice Chair Peter A. Wilson, Board Treasurer Board of Directors [FY 20 July 1, 2019 – June 30, 2020] Robert Beal LeeAnn Horner, LICSW Rory Browne, D. Phil. Ronnie Kanarek Gordon Carr Mark A. Kelley, M.D. Gordon Clagett Christy Keswick Francesco A. De Vito Walter J. Little James B. Dunbar Jeanne Pinado Thomas P. Feeley Claudia U. Richter, M.D. Ruth Ellen Fitch Peter Roberts Mark Giovino Colin Van Dyke Kate Guedj Kathleen Vieweg, M.Ed. Steven M. Hinterneder, P.E. Advisory Council [FY 20 July 1, 2019 – June 30, 2020] OFFICERS: Kathleen Vieweg, Advisory Council Chair Lloyd Hamm, Advisory Council Vice Chair MEMBERS: Alexis Belash Danio Mastropieri Joanna Berube Quincy Miller Melissa Buckingham Jessica Gifford Nigrelli Bill Byrne Susan Oman Thomas Comeau Sean L. -

FIELD PHILOSOPHY Final Schedule June 9.Pdf

Field Philosophy and Other Experiments École normale supérieure, Paris, France, 23-24 June 2017 New interdisciplinary methodological practices have emerged within the environmental humanities over the last decade, and in particular there has been a noticeable movement within the humanities to experiment with field methodologies in order to critically address environmental concerns that cross more-than-disciplinary concepts, theories, narratives, and practices. By exploring relations with (and between) human communities, nonhuman animals, plants, fungi, forests, microbes, scientific practices, and more, environmental humanities scholars are breaking with traditional methodological practices and demonstrating that the compositions of their study subjects – e.g., extinction events, damaged landscapes, decolonization, climate change, conservation efforts – are always a confluence of entangled meanings, actors, and interests. The environmental humanities methodologies that are employed in the field draw from traditional disciplines (e.g., art, philosophy, literature, science and technology studies, indigenous studies, environmental studies, gender studies), but they are (i) importantly reshaping how environmental problems are being defined, analyzed, and acted on, and (ii) expanding and transforming traditional disciplinary frameworks to match their creative methodological practices. Recent years have thus seen a rise in new methodologies in the broad area of the environmental humanities. “Field philosophy” has recently emerged as a means of engaging with concrete problems, not in an ad hoc manner of applying pre-established theories to a case study, but as an organic means of thinking and acting with others in order to better address the problem at hand. In this respect, field philosophy is an addition to other field methodologies that include etho-ethnology, multispecies ethnography and multispecies studies, philosophical ethology, more-than-human participatory research, extinction studies, and Anthropocene studies. -

![2016 Annual Report [July 1, 2015 – June 30, 2016] WHO WE ARE](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/2586/2016-annual-report-july-1-2015-june-30-2016-who-we-are-632586.webp)

2016 Annual Report [July 1, 2015 – June 30, 2016] WHO WE ARE

Inspiring CARING and ACTION on behalf of wildlife and conservation FISCAL YEAR 2016 Annual Report [July 1, 2015 – June 30, 2016] WHO WE ARE Zoo New England is the non-profit organization responsible for the operation of Franklin Park Zoo in Boston and Stone Zoo in Stoneham, Mass. Both are accredited by the Association of Zoos and Aquariums (AZA). Zoo New England’s mission is to inspire people to protect and sustain the natural world for future generations by creating fun and engaging experiences that integrate wildlife and conservation programs, research and education. To learn more about our Zoos, education programs and conservation efforts, please visit us at www.zoonewengland.org. Board of Directors Officers [FY16: July 1, 2015 – June 30, 2016] David C. Porter, Board Chair Janice Houghton, Board Vice Chair Peter A. Wilson, Board Treasurer Board of Directors [FY16: July 1, 2015 – June 30, 2016] Robert Beal Christy Keswick Rory Browne, D.Phil. Walter J. Little Gordon Carr Christopher P. Litterio Gordon Clagett Quincy L. Miller Francesco A. De Vito David Passafaro James B. Dunbar Jeanne Pinado Bruce Enders Claudia U. Richter, M.D. Thomas P. Feeley Peter Roberts David Friedman Jay Kemp Smith Kate Guedj Colin Van Dyke Steven M. Hinterneder, P.E. Kathleen Vieweg, M.Ed. Mark A. Kelley, M.D. Advisory Council [FY16: July 1, 2015 – June 30, 2016] OFFICERS: Kathleen Vieweg, Advisory Council Chair Lloyd Hamm, Advisory Council Vice Chair MEMBERS: Alexis Belash Danio Mastropieri Joanna Berube Diana McDonald Bill Byrne David J. McLachlan Elizabeth Cook John MacNeil Donna Denio Mitsou MacNeil Beatrice Flammia Ruth Marrion, DVM Mark Gudaitis, CFA Jessica Gifford Nigrelli Jackie Henke Gauri Patil Punjabi David Hirschberg Terry Schneider LeeAnn Horner Kate Schwartz Elizabeth Duffy Hynes Steven D. -

This Summer with Children Age 2-8

NATURE-THEMED FREE & LOW COST THINGS TO DO This Summer with Children Age 2-8 July 5 Curious Creatures Show at Boardinghouse Park, 40 French St, Free Lowell, for All Ages 10:00 Arts & Crafts & snacks, 11:00 show, 12:00 trolley rides, www.lowellsummermusic.org/kids July 5 The Caterpillar Lab visits Harvard Public Library, 1-4:00 p.m., for All Ages – Drop in Free See a huge variety of New England caterpillars munching on food right in front of you. Learn about metamorphosis and other incredible but true stories about these creatures such as camouflaged or big-as-a-hotdog caterpillars! www.harvardpubliclibrary.org. 4 Pond Road July 6, 13, 20 Open Farmyard Drop in Program for Ages 2 ½ to 7 at Land’s Sake Farm in Weston, 3-5:00 Free 27, Aug. 3, 10, Young children and their caregivers will hear stories, pick and plant crops, explore the chicken 17, 24, 31 coop and more at this working CSA farm. 90 Wellesley Street. Canceled if rain. Donation welcome. July 8 Learn About Honey Bees at The Discovery Museum Today from 11:00-2:00, for all ages *Free w/ Researcher Racel Bonoan from Tufts University will be at the museum to help you test your Admission bee vision, let you taste honey from different locations, and make a beeswax candle as you @ $6.50 ea. learn about honey bees’ importance. *Price is with a library pass from any town. Age 1 & up July 10 Goodnow Library Builds Bird Feeders for Ages 4 and Up, 4:00-5:00 p.m. -

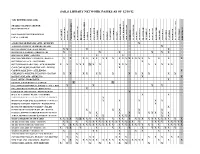

Sails Library Network Passes As of 12/10/12

SAILS LIBRARY NETWORK PASSES AS OF 12/10/12 *DECERTIFIED LIBRARIES SHADED COLUMNS ARE FOR RESIDENTS ONLY M PASS POLICIES DETERMINED BY SON BRIDGEWATER ATTLEBORO BRIDGEWATER . LOCAL LIBRARY * . BRIDGEWATER * * ATTLEBORO BERKLEY CARVER DARTMOUTH DIGHTON E EASTON FAIRHAVEN RIVER FALL FOXBORO FREETOWN HALIFAX HAN LAKEVILLE MANSFIELD MARION MATTAPOISETT MIDDLEBOROUGH BEDFORD NEW NORFOLK N NORTON PEMBROKE PLAINVILLE PLYMPTON RAYNHAM REHOBOTH ROCHESTER SEEKONK SOMERSET SWANSEA TAUNTON WAREHA W WESTPORT WRENTHAM ACUSHNET ALDEN HOUSE HISTORIC SITE - DUXBURY X AUDUBON SOCIETY OF RHODE ISLAND X BATTLE SHIP COVE - FALL RIVER X X X X BLITHWOLD GARDEN - BRISTOL, RI X X X X X X BOSTON BY FOOT - BOSTON X X BOSTON CHILDREN’S MUSEUM - BOSTON X X X X X X X X X X X X X X X X X X X X X BUTTERFLY PLACE - WESTFORD X BUTTONWOOD PARK ZOO - NEW BEDFORD X X X X X X X X X X X X X X X X CAPE COD MUSEUM OF FINE ART - DENNIS X CAPRON PARK ZOO - ATTLEBORO X CHILDREN’S MUSEUM IN EASTON - EASTON X X X X X X X X X X X X X DAVIS FARMLAND - STERLING X X ECOTARIUM - WORCESTER X EDAVILLE RAILROAD - S. CARVER X X FALL RIVER HISTORICAL SOCIETY - FALL RIVER X X X X FULLER CRAFT MUSEUM - BROCKTON X GARDEN IN THE WOODS - FRAMINGHAM X HALL AT PATRIOT PLACE - FOXBORO X X HARVARD MUSEUM OF NATURAL HISTORY - CAMBRIDGE X HERITAGE MUSEUMS & GARDENS -SANDWICH X X X X X HIGGINS ARMORY MUSEUM - WORCESTER X HOUSE OF THE SEVEN GABLES - SALEM X INSTITUTE OF CONTEMPORARY ART - BOSTON X X X X X ISABELLA STEWART GARDNER MUSEUM - BOSTON X X X X X X X X X X JOHN F. -

Additional Member Benefits Reciprocity

Additional Member Benefits Columbus Member Advantage Offer Ends: December 31, 2016 unless otherwise noted As a Columbus Zoo and Aquarium Member, you can now enjoy you can now enjoy Buy One, Get One Free admission to select Columbus museums and attractions through the Columbus Member Advantage program. No coupon is necessary. Simply show your valid Columbus Zoo Membership card each time you visit! Columbus Member Advantage partners for 2016 include: Columbus Museum of Art COSI Franklin Park Conservatory and Botanical Gardens (Valid August 1 - October 31, 2016) King Arts Complex Ohio History Center & Ohio Village Wexner Center for the Arts Important Terms & Restrictions: Receive up to two free general admissions of equal or lesser value per visit when purchasing two regular-priced general admission tickets. Tickets must be purchased from the admissions area of the facility you are visiting. Cannot be combined with other discounts or offers. Not valid on prior purchases. No rain checks or refunds. Some restrictions may apply. Offer expires December 31, 2016 unless otherwise noted. Nationwide Insurance As a Zoo member, you can save on your auto insurance with a special member-only discount from Nationwide. Find out how much you can save today by clicking here. Reciprocity Columbus Zoo Members Columbus Zoo members receive discounted admission to the AZA accredited Zoos in the list below. Columbus Zoo members must present their current membership card along with a photo ID for each adult listed on the membership to receive their discount. Each zoo maintains their own discount policies, and the Columbus Zoo strongly recommends calling ahead before visiting a reciprocal zoo. -

2019 Zoo New England Reciprocal List

2019 Zoo New England Reciprocal List State City Zoo or Aquarium Reciprocity Contact Name Phone Number CANADA Calgary - Alberta Calgary Zoo 50% Stephenie Motyka 403-232-9312 Quebec – Granby Granby Zoo 50% Mireille Forand 450-372-9113 x2103 Toronto Toronto Zoo 50% Membership Dept. 416-392-9103 MEXICO Leon Parque Zoologico de Leon 50% David Rocha 52-477-210-2335 x102 Alabama Birmingham Birmingham Zoo 50% Patty Pendleton 205-879-0409 x232 Alaska Seward Alaska SeaLife Center 50% Shannon Wolf 907-224-6355 Every year, Zoo New England Arizona Phoenix The Phoenix Zoo 50% Membership Dept. 602-914-4365 participates in a reciprocal admission Tempe SEA LIFE Arizona Aquarium 50% Membership Dept. 877-526-3960 program, which allows ZNE members Tucson Reid Park Zoo 50% Membership Dept. 520-881-4753 free or discounted admission to other Arkansas Little Rock Little Rock Zoo 50% Kelli Enz 501-661-7218 zoos and aquariums with a valid California Atascadero Charles Paddock Zoo 50% Becky Maxwell 805-461-5080 x2105 membership card. Eureka Sequoia Park Zoo 50% Kathleen Juliano 707-441-4263 Fresno Fresno Chaffee Zoo 50% Katharine Alexander 559-498-5938 Los Angeles Los Angeles Zoo 50% Membership Dept. 323-644-4759 Oakland Oakland Zoo 50% Sue Williams 510-632-9525 x150 This list is amended specifically for Palm Desert The Living Desert 50% Elisa Escobar 760-346-5694 x2111 ZNE members. If you are a member Sacramento Sacramento Zoo 50% Brenda Gonzalez 916-808-5888 of another institution and you wish to San Francisco Aquarium of the Bay 50% Jaz Cariola 415-623-5331 visit Franklin Park Zoo or Stone Zoo, San Francisco San Francisco Zoo 50% Nicole Silvestri 415-753-7097 please refer to your institution's San Jose Happy Hollow Zoo 50% Snthony Teschera 408-794-6444 reciprocal list.