Soldiers of Conscience Release

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Participant Biographies Genesis Abreu Steve Adams Zelalem Adefris

Climate Resilience and Urban Opportunity Initiative Grantee Convening June 14 – 16, 2017 | Detroit, MI Westin Book Cadillac Hotel Participant Biographies Genesis Abreu Bilingual Community Organizer- WE ACT for Environmental Justice As the Bilingual Community Organizer, Genesis is tasked with strengthening the WE ACT membership by recruiting more Spanish-speaking residents in Northern Manhattan. She hopes to continue to collaborate in local efforts in confronting environmental injustices in her community. Prior to working at WE ACT, Genesis was awarded a Fulbright Research Grant to study the impacts of climate change in agricultural practices in Quechua indigenous communities in Peru. Steve Adams Director - Urban Resilience- Institute for Sustainable Communities As the Director of Urban Resilience at the Institute for Sustainable Communities, Steve works to identify, catalyze and scale break-through opportunities to advance urban sustainability and resilience. Since leaving government in 2009, Steve has led community-based and sector-based adaptation projects in Oregon, helped catalyze the Southeast Florida Regional Climate Change Compact as a model for metro- regional scale climate governance and co-founded the American Society of Adaptation Professionals to serve as a community of practice for professionals working in various sub-fields of climate adaptation. From 2007-2009, Steve served as an energy and climate change policy advisor to Florida Governor Charlie Crist. Previously, he served in a number of roles at Florida's Department of Environmental Protection. In 2002-2003, he served as Senior Advisor to U.S. EPA Administrator Christie Todd Whitman’s Environmental Indicators Initiative. Zelalem Adefris Climate Resilience Program Manager- Catalyst Miami Zelalem Adefris is the Climate Resilience Program Manager at Catalyst Miami. -

Newsletter December 2019

Olympia/Santo Tomás An update from the Update Thurston–Santo Tomás US/Nicaragua Solidarity–Since 1989 Sister County December 2019 Association Dear friends of Santo Tomás, Our last newsletter had personal reflections from Santo Tomás about the crisis from two very distinct It’s been a long time since those of us active in the perspectives in support of, and against, the Nicara- TSTSCA have created and sent out a newsletter. In- guan government. You can find and reread it on our creasing economic injustice and violence across the infrequently updated webpage https://oly-wa.us/ planet is overwhelming but global resistance contin- TSTSCA/. This December 2019 newsletter has a lo- ues to grow and inspire action. From the climate crisis cally written critique of the role of some Non-Govern- to the crisis at the Southern border of the US, from mental Organizations on the global south and their Hong Kong to Chile to Colombia, Northern Syria to financing by interested, controlling parties such as the Yemen and Palestine, to the coup d’etat in Bolivia, US government. There is also an article drawn from let us each find where we can take a role in creating a monthly Nicaraguan publication that analyses the the change we desperately need to enact. In Nicara- state repression in their country. The TST- gua, the situation is still complicated SCA continues to hold firm in and, frankly, hard to really grasp. our belief that Nicaragua is a Our friends there are exhausted sovereign state in which our from weathering the chal- government has no right lenges of the political un- to intervene, but which has rest and economic impact done so for over 150 years. -

THE MOST DANGEROUS MAN in AMERICA: Daniel Ellsberg and the Pentagon Papers

THE MOST DANGEROUS MAN IN AMERICA: Daniel Ellsberg and the Pentagon Papers A film by Judith Ehrlich and Rick Goldsmith USA – 2009 – 94 Minutes Special Jury Award - International Documentary Film Festival Amsterdam (IDFA) “Freedom of Expression Award” & One of Top Five Documentaries - National Board of Review Audience Award, Best Documentary - Mill Valley (CA) Film Festival Official Selection - 2009 Toronto International Film Festival Official Selection - 2009 Vancouver Film Festival Official Selection - WatchDocs, Warsaw, Poland Contacts Los Angeles New York Nancy Willen Julia Pacetti Acme PR JMP Verdant Communications 1158 26th St. #881 [email protected] Santa Monica, CA 90403 (917) 584-7846 [email protected] (310) 963-3433 THE MOST DANGEROUS MAN IN AMERICA: Daniel Ellsberg and the Pentagon Papers Selects from reviews of The Most Dangerous Man in America: “Riveting! A straight-ahead, enthralling story of moral courage. This story changed the world. The movie offers one revelatory interview after another. CRITICS’ PICK!” – David Edelstein, New York magazine “Detailed, clearly told, persuasive” – Mike Hale, The New York Times “A Must-See! Crams a wealth of material into 90 minutes without losing clarity or momentum. Focuses on (Ellsberg’s) moral turnaround, which directly impacted history. A unique fusion of personal and social drama.” – Ronnie Scheib, Variety “The filmmakers do an astounding job… earnest, smart documentary… "The Most Dangerous Man" offers a brisk and eye-opening approach to recent history.” – Chris Barsanti, Hollywood Reporter “The most exciting thriller I’ve seen in a while… as powerful as anything Hollywood can throw at us.” – V.A. Musetto, New York Post “The essential new documentary. -

Spring 2010 Number 1 “We Are All Conscientious Objectors”

The Reporter The Center on for Conscience’ Sake Conscience & War Volume 67 Spring 2010 Number 1 “We are All Conscientious Objectors” Joshua Casteel, J.E. McNeil, Bill Galvin & Camilo Mejia Chris Hedges Jake Diliberto Former Boardmembers Titus Peachy, David Miller with J.E. McNeil and Bill Galvin at Riverside Church, New York during the Truth Commision on Conscience Rick Ufford-Chase, Truth Commision on Conscience Presbyterian Peace Fellowship Also Inside: by Bill Galvin On March 21st and 22nd approximately 80 com- J.E. McNeil choose a striking manner in which to News Briefs.....................Page 2 missioners gathered at the historic Riverside emphasize how critically important it is to expand Church in New York City for a Truth Commis- the concept of conscientious objection beyond the CCW News......................Page 3 sion on Conscience in War. CCW had a prominent narrow scope currently recognized by the United role in the Commission: J.E. McNeil was among States government. Having outlined a history of • New Development Director the testifiers. Bill Galvin and Daniel Lakemacher the recognition of the role of conscience in war, were commissioners, as were three former CCW she went on to explain how advocacy on this vast • Selective Service System board members. and significant issue cannot rightly be seen as • Meeting in Goshen, IN the sole responsibility of any one group, whether On the evening of the 21st, J.E. McNeil gave a that group has been historically recognized as a Truth Comission passionate speech in the same place that Dr. Mar- “peace church” or not. At a conference that in- on Conscience................Page 4 tin Luther King made his famous “Beyond Viet- cluded attendees of vastly different religious and nam” speech crying out for peace in 1967. -

The Conscientious Objector As (Anti) War Hero

SARA Deutch SCHOTLAND Soldiers of Conscience: The Conscientious Objector as (Anti) War Hero he producers of Soldiers of Conscience (Catherine Ryan and Gary Weinberg) claim that theirs “is not a film that tells an audience what to think, nor is it about the situation in Iraq today. Instead, it tells a bigger story about Thuman nature and war,” and the mental burdens carried by soldiers who have killed in combat.1 Notwithstanding the producers’ claims that they do not intend to tell their audience what to think about the War in Iraq, Soldiers of Conscience illustrates Bruce Gronbeck’s thesis that documentary is never neutral but is an inherently rhetorical medium.2 I argue that the film has a three-fold strategy: to heroicize the soldier who refuses to fight as a righteous and courageous “fighter” for principle; to criticize current U.S. policy which denies conscientious objector status to those who argue that their service in Iraq constitutes a war crime; and to emphasize the dangers of training troops to engage in reflexive killing. The Courage of Resistance Soldiers of Conscience deconstructs the stereotype that soldiers who seek C.O. status are fakers, cowards, and traitors. The documentary tracks four soldiers who rejected combat after becoming horrified by the brutality of war in Iraq and, in particular, civilian casualties. Two of the soldiers, Joshua Casteel and Aiden Delgado, were granted C.O. status; however, Kevin Benderman and Camilo Mejía were convicted of desertion and served time in jail before being dishonorably discharged.3 In this “character documentary,” we get to know each man through photos of his childhood and his family. -

Information and Resources from Non-Governmental Organizations

Information and Resources from Non-Governmental Organizations In Harms Way Source: Veterans for Peace http://www.veteransforpeace.org/In_harm_s_Way.pdf Thorough treatment of how the military markets enlistment, along with a hard look at the realities behind all the recruitment hype from veterans who know what they are talking about. Good documentation and links to many other good resources. A Guide for Alternatives to the Military Source: Boston Direct Action Project http://bostondirectactionproject.blogspot.com/ A booklet with local/regional information on options for jobs, job training, internships, and education for young people seeking alternatives to the military. A good model for local communities wanting to make alternatives to the military easily accessible to youth. Your Life, Your World, Make them Great Source: American Friends Service Committee Coalition Against Militarism in our Schools http://www.afsc.org/pacificsw/counterrecruitment.htm Alternatives to the Military booklet describing career, job-training and education options in southern California, with some national agencies also listed. A good model for local communities wanting to make alternatives to the military easily accessible to youth. Military Recruitment Source: National Priorities Project http://database.nationalpriorities.org/ Find out the number of new military recruits in 2004 coming from your high school, county, zip code and state. Get analysis with tables and charts explaining who these recruits are in terms of income levels, race/ethnicity and more. A powerful information tool for local activism. Opt-Out: Guide to No Child Left Behind Act Source: Resource Center for Nonviolence http://www.rcnv.org/counterrecruit/optout/ Thorough treatment of the Act that requires schools to release student contact information to military recruiters, but allows individual students/parents to opt out of this requirement. -

2008-2 0-Inhalt.Indd

www.ssoar.info De-militarizing masculinities in the age of empire Sharoni, Simona Veröffentlichungsversion / Published Version Zeitschriftenartikel / journal article Empfohlene Zitierung / Suggested Citation: Sharoni, S. (2008). De-militarizing masculinities in the age of empire. Österreichische Zeitschrift für Politikwissenschaft, 37(2), 147-164. https://nbn-resolving.org/urn:nbn:de:0168-ssoar-281596 Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Dieser Text wird unter einer CC BY-NC Lizenz (Namensnennung- This document is made available under a CC BY-NC Licence Nicht-kommerziell) zur Verfügung gestellt. Nähere Auskünfte zu (Attribution-NonCommercial). For more Information see: den CC-Lizenzen finden Sie hier: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0 https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/deed.de De-Militarizing Masculinities in the Age of Empire 147 Simona Sharoni (New York) De-Militarizing Masculinities in the Age of Empire Dieser Artikel untersucht kritisch die Beziehung zwischen Männern, vorherrschenden Männlichkeitskonzeptionen und den Prozessen und Praktiken, die ins Spiel kommen, wenn Männlichkeiten militarisiert und zum Kriegszweck eingesetzt werden. Nach einer einleiten- den Übersicht über die feministische und nicht-feministische Literatur zu Militarisierung und Männlichkeitskonstruktionen konzentriert sich der Artikel auf die Aussichten für eine Demilitarisierung von Männern und Männlichkeitskonstruktionen im US-Empire seit dem 11. September 2001 und insbesondere im Kontext der Kriege in Afghanistan und im Irak unter der Führung der USA. Die Analyse unterscheidet zwischen dem Militär als System, Militarisierung als Prozess und Soldaten als Menschen. Da Kriege nicht ohne militarisier- te Männlichkeit zu führen sind, helfen Kriegsgeschichten von Soldaten, die zu einer Demys- tifizierung des Krieges beitragen, auch die enge Verknüpfung zwischen Männlichkeit und Gewalt zu schwächen oder sogar aufzubrechen. -

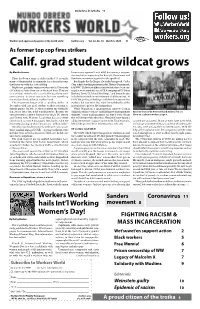

Calif. Grad Student Wildcat Grows

Ciudadano de la troika 12 Workers and oppressed peoples of the world unite! workers.org Vol. 62, No. 10 March 5, 2020 $1 As former top cop f ires strikers Calif. grad student wildcat grows By Martha Grevatt bureaucracy opposed Local 2865 for passing a progres- sive resolution supporting the Boycott, Divestment and There has been a surge of strikes in the U.S. recently, Sanctions movement against Israeli apartheid. many of them fueled by demands for a decent income But despite the challenges, the strike has spread. Carlos that keeps up with the cost of living. Cruz, a fired teaching assistant in the History Department, Right now, graduate student workers at the University told WW: “Folks from different universities have been out- of California Santa Cruz are on the front lines. They are raged so we’ve started to see a COLA campaign at UC Santa on a wildcat strike to win a cost-of-living allowance— Barbara, Davis, UCLA and San Diego,” and demands also once common in union contracts, but now something include the immediate reinstatement of all those fired. At few workers have and most workers need. UCSC the grading strike began with less than 250 student The movement began with a “grading strike” in workers, but now twice that many have pledged to strike December with 233 grad student workers refusing to next quarter to protest the terminations. submit grades. On Feb. 17, they escalated the withhold- While Napolitano’s spokesperson Andrew Gordon ing of their labor into a full teaching strike. Because the claims the strikers’ actions “unfairly impact undergraduate Grad students at UC Riverside back strikers, Feb. -

For Conscience' Sake

The Reporter The Center on Conscience & War for Conscience’ Sake Volume 62 2005 Number 3 direct order from someone of authority. However, it was Army Teaches Killing In discovered that it was fear of killing, rather than the fear of being killed, that largely influenced the actions of these War Is Moral soldiers. Even when there was a perceived threat to the A Response to Work of Major Peter Kilner soldiers, relatively few actually fired their weapons. By Bill Galvin General S.L.A. Marshall, one of the official historians of CCW Counseling Coordinator WWII wrote, “[The American soldier] is what his home, his religion, his schooling, and the moral code and ideals On Aug 17, 2005 the Wall Street Journal reported that of his society have made him. .He comes from a Major Peter Kilner’s articles on the ethics and morality of civilization in which aggression, connected with the taking war have been receiving wider attention. “At the Army’s of life, is prohibited and unacceptable. .[this teaching] school for newly minted chaplains in South Carolina, has been expressed to him so strongly and absorbed by Major Kilner’s writings are being incorporated into a new him so deeply and pervadingly– practically with his course to be offered later this year on how to counsel mothers milk– that it is part of a normal mans emotional soldiers on the morality of war.” Possessing a seeming make-up. This is his great handicap when he enters fascination with this issue and believing the military to combat” Marshall notes that “at the vital moment [the have ignored the matter of morality when training soldiers rifleman] becomes a conscientious objector.”2 to kill effectively, Kilner has produced several recent publications, beginning with his Master’s thesis, Soldiers, See KILNER, Pg. -

Amnesty International and Nicaragua: Why Does AI Refuse to Listen to Criticism About Its Work?

Amnesty International and Nicaragua: Why does AI refuse to listen to criticism about its work? A briefing by the Nicaragua Solidarity Campaign Action Group Amnesty International has repeatedly criticised Daniel Ortega’s government, disregarding its massive achievements in tackling real human rights issues in Nicaragua such as significantly reducing levels of severe poverty, massively improving health services and addressing gender inequality. Why is Amnesty International doing this? And why does it reject any criticism and fail to respond when it gets things wrong? In this briefing written for NSCAG by John Perry, an NSC member living in Nicaragua, we look at AI’s blinkered campaign over the past three years and its refusal to abide by its own rules. Armed protesters at La Trinidad, near Estelí: one of the multiple roadblocks set up across Nicaragua by opposition forces in May-June 2018, and where much of the violence took place Amnesty International and Nicaragua Amnesty International’s role No one can fairly argue that Amnesty International shouldn’t be a fierce critic of governments, that’s part of their job. As they say themselves, ‘No government is beyond scrutiny’. But it’s also part of their job to be fair and balanced. AI’s core values include ‘impartiality and independence’ and since 2001 AI claims to address issues of human rights not just at government level but among ‘armed political groups, companies and other non-state actors’. However, this requires it to recognise that the political groups are armed, which in Nicaragua’s case AI consistently fails to do. AI states that their vision is ‘a world in which every person is able to enjoy the human rights enshrined in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and other international human rights standards.’ Articles 25, 26, and 27 of the declaration refer to economic, social and cultural rights which are indivisible from political and civil rights. -

Amnesty International Group 22 Pasadena/Caltech News

Amnesty International Group 22 Pasadena/Caltech News Volume XII Number 10, October 2004 Sudan and a different conflict than the one featured in UPCOMING EVENTS “Lost Boys”). Everyone was given a packet with Thursday, October 28, 7:30 PM. Monthly information on Sudan, with letters to send to Meeting Caltech Y has moved. New Location! Sudanese officials and other resources. It was an interesting and informative evening and I hope that Just around the corner from our old meeting the new people who came will come to one of our place, we move to San Pasqual between Hill regular meetings. and Holliston, south side. You will see two curving walls forming a gate to a path-- our There will be an interfaith candlelight march for building is just behind that sign. Help us plan Sudan on Monday October 25 at 7 PM beginning at future actions on Tibet, the Patriot Act, the Islamic Center, 434 S. Vermont Ave, Los Angeles. For information, contact 323-761-8350 or 213-482-2040 Campaign Against Discrimination, death ext 245. This is sponsored by Progressive Jewish penalty, environmental justice and more. Alliance and Progressive Christians Uniting. This is Tuesday, November 9, 7:30 PM. Letter- not an Amnesty event, but may be of interest. writing Meeting at the Athenaeum. Corner of Group 22 is participating in the Doo-Dah Parade again California & Hill. We are back in our usual this year, which will be on November 21st, a Sunday. location in the basement recreation area. Come to our monthly meeting this next week, This informal gathering is a great for Thursday October 28, to see what’s happening and newcomers to get acquainted with Amnesty! how you can be a part of it! We need volunteers! (For those who don’t know, Doo-Dah is a hilarious spoof Sunday, November 21, 9:00 AM-2:00 PM of the Rose Parade). -

UNAC Conference 2020 Rise Against Racism, Militarism and the Climate Crisis Building Power Together

UNAC Conference Journal and Website Compliments of Papillonweb Development, 2020 [email protected] UNAC Conference 2020 Rise Against Racism, Militarism and the Climate Crisis Building Power Together A National Conference Hosted by The United National Antiwar Coalition (UNAC) February 21-23, 2020 at: The Peoples Forum 320 West 37th Street (between 8th & 9th Avenues) New York, NY 10018 The United National Antiwar Coalition (UNAC) has made great strides since its 2017 conference which was held in Richmond, Virginia. Since that time new organizations have joined our coalition. Our members have traveled as part of delegations to Venezuela, Ukraine, Syria and Cuba. We have held conferences on U.S./NATO military bases in Baltimore, Maryland and Dublin, Ireland. We have organized against the militarization of police departments, AFRICOM, and punishing sanctions against other nations. Our members prevented the illegal Venezuelan coup government from taking over the Washington embassy, while others walked picket lines with striking workers. In 2020 we mobilize against ecocide, white supremacist policy and war in all its forms. We gather to put the issue of peace before the voters in an election year and to protest against anti-immigrant policies. Our principles of unity will be strengthened as we gather to stop the wars at home and abroad. The UNAC conference will be a place where we deepen that unity and build the our movement for the next stage of struggle. Schedule Friday: 6:00 PM: Doors Open and Registration 7:00 PM: Panel: Opposing Imperialist