Love's Labour's Lost

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Peter Freeman

First Assistant Director Peter Freeman 30 Birch Grove Windsor, Berks SL4 5RT Tel : +44 (0)1753 862226 Mobile: +44 (0)7774 700 747 SA Mobile: +27 (0)76 4377 963 e-mail: [email protected] Languages: Greek, Basic French Over 12 years experience with Movie Magic Scheduling. South African ResidenceVisa. Advanced Production Safety Certificate, BBC Total Concept Safety Certificate Recent credits include: FEATURES “Gulliver’s Travels” Jack Black as Gulliver in modern retelling of classic tale. (Additional Assistant Director) Cast Inc: Jack Black, Jason Segel, Billy Connolly, Emily Blunt. Directors: Chris O’Dell (2nd Unit), UPM/1st AD: Terry Bamber (2nd Unit), “Broken Thread” Modern day ghost story. Shot in India, Isle of Man and London. Cast inc: Linus Roache, Saffron Burrows Director: Mahesh Matai Producer: Deepak Nayar A.P: Paul Sarony “These Foolish Things” Romantic comedy set in 1920’s theatre-land. Shot in and around Cheltenham. Cast inc: Angelica Huston, Lauren Bacall, Terence Stamp, Andrew Lincon. Director: Julia Taylor-Stanley Producers: Julia Taylor-Stanley, Paul Sarony “Spirit Trap” Horror/ghost story. Shot in Romania and the UK for Archangel Productions. Cast inc: Luke Mably, Sam Troughton, Emma Catherwood and Billy Piper. Director: David Smith Producer: Susie Brooks-Smith A.P: David Higginson / Cathy Lord “Chasing Liberty” Second unit Czech Republic. Cast inc: Mandy Moore, Mark Harmon Director: Andy Cadiff (main unit) Line Prod: Cathy Lord A.P: Hilary Benson “Jane Eyre” Retelling of classic tragic love story. Derbyshire & London Cast inc: William Hurt, Charlotte Gainsburg, Elle Macpherson Director: Franco Zeffirelli Producer: Dyson Lovell A.P: Ray Freeborn Page 2 “Soft Sand, Blue Sea” Film Four. -

Drama Book Shop Became an Independent Store in 1923

SAVORING THE CLASSICAL TRADITION IN DRAMA ENGAGING PRESENTATIONS BY THE SHAKESPEARE GUILD I N P R O U D COLLABORATION WIT H THE NATIONAL ARTS CLUB THE PLAYERS, NEW YORK CITY THE ENGLISH-SPEAKING UNION SALUTING A UNIQUE INSTITUTION ♦ Monday, November 26 Founded in 1917 by the Drama League, the Drama Book Shop became an independent store in 1923. Since 2001 it has been located on West 40th Street, where it provides a variety of services to the actors, directors, producers, and other theatre professionals who work both on and off Broadway. Many of its employees THE PLAYERS are young performers, and a number of them take part in 16 Gramercy Park South events at the Shop’s lovely black-box auditorium. In 2011 Manhattan the store was recognized by a Tony Award for Excellence RECEPTION 6:30, PANEL 7:00 in the Theatre . Not surprisingly, its beneficiaries (among them Admission Free playwrights Eric Bogosian, Moises Kaufman, Lin-Manuel Reservations Requested Miranda, Lynn Nottage, and Theresa Rebeck), have responded with alarm to reports that high rents may force the Shop to relocate or close. Sharing that concern, we joined The Players and such notables as actors Jim Dale, Jeffrey Hardy, and Peter Maloney, and writer Adam Gopnik to rally support for a cultural treasure. DAKIN MATTHEWS ♦ Monday, January 28 We look forward to a special evening with DAKIN MATTHEWS, a versatile artist who is now appearing in Aaron Sorkin’s acclaimed Broadway dramatization of To Kill a Mockingbird. In 2015 Dakin portrayed Churchill, opposite Helen Mirren’s Queen Elizabeth II, in the NATIONAL ARTS CLUB Broadway transfer of The Audience. -

The District Messenger

THE DISTRICT MESSENGER The Newsletter of the Sherlock Holmes Society of London Roger Johnson, Mole End, 41 Sandford Road, Chelmsford CM2 6DE no. 154 30th September 1995 Jeremy Brett died on the 12th September, not of a broken heart, but of an overworked heart. He had come to terms with his precarious condition, and knew that his only chance of cardiac stability was a heart transplant, an option he had considered and rejected. The cardiomyopathy was not correctly diagnosed until comparatively late, but it was this rather than his manic- depression that made his later performances as Sherlock Holmes so uneven, though the tabloids made the most of the latter. Jeremy Brett played Holmes in 41 television productions and one stage play. For more than three- quarters of the time he was a great Sherlock Holmes. In Pace Requiescat. The next issue of The Sherlock Holmes Gazette will be a Jeremy Brett memorial issue. Look out for it. Admirers of John Doubleday's famous statue of Holmes in Meiringen, Switzerland, will be pleased to learn that the sculptor has been persuaded to produce a miniature version in cold-cast bronze on a mahogany base. The height of the statuette, without the base, is 6½” (160mm), and the price is a maximum of £77.55 including VAT (plus postage of £4.45 = total £82.00). It's available from Albert Kunz, 20 Highfield Road, Chislehurst, Kent BR7 6QZ (phone 01689 836256). Cheques should be payable to A. Kunz; they won't be cashed until the statuettes are sent out. As mentioned in the last DM, Calabash Press (Barbara & Christopher Roden, Ashcroft, 2 Abbottsford Drive, Penyffordd, Chester CH4 OJG) will issue its first publication on 15th October, The Tangled SkeinSkein by David Stuart Davies, whose first, very limited edition is no longer obtainable. -

The District Messenger

THE DISTRICT MESSENGER The Newsletter of the Sherlock Holmes Society of London Roger Johnson, Mole End, 41 Sandford Road, Chelmsford CM2 6DE no. 156 4th December 1995 Sir Robert Stephens died on the 12th November. We who treasure that wonderful idiosyncratic film The Private Life of SherlockSherlock Holmes were put in our place by the obituaries, all of which dismissed it as a resounding flop. Stephens flourished mainly in the theatre, and he did actually play Sherlock Holmes on stage, in Toronto in 1976, in the RSC production of William Gillette's play. Like his friend Jeremy Brett, he really hit his stride in the last ten years of his life, especially as Falstaff and Lear. He was knighted last January. Lady Stephens was among the many friends and family who attended Jeremy Brett's memorial service last Wednesday at St Martin-in-the-Fields. The Sherlock Holmes Society of London, the Northern Musgraves, the BSI, the ASH, the Arthur Conan Doyle Society, the Société Sherlock Holmes de France, the Poor Folk Upon The Moors, and other groups were represented at the service, which was organised by Granada Television. Reports appeared in The Times and the Daily Telegraph the next day. Philip Attwell notes that plans to broadcast a tribute to Brett have been dropped, though BBC TV showed The Private Life last night in tribute to Robert Stephens. (*Last week's late film was the Hammer Hound of the BaskervillesBaskervilles; the Radio Times claimed that "Holmes scholars" regard it as the definitive version! I'd suggest that the BBC's own 1968 production, with Peter Cushing and Nigel Stock, more nearly fits that description. -

The Representation, Interpretation and Staging of Magic in Renaissance Plays from the Sixteenth Century Onwards

Ghent University Faculty of Arts and Philosophy The representation, interpretation and staging of magic in Renaissance plays from the sixteenth century onwards. A case study of William Shakespeare’s The Tempest, Macbeth and Cristopher Marlowe’s Doctor Faustus. Supervisor: Paper submitted in partial Professor Doctor fulfilment of the requirements for Sandro Jung the degree of “Master in de Taal- en Letterkunde: English-Spanish” by Tine Dekeyser August 2014 Word count: 27334 Dekeyser i Acknowledgments First of all, I would like to thank my supervisor, Professor Doctor Sandro Jung, for granting me the opportunity to continue working on the same topic of my BA-dissertation and for guiding me towards a more profound investigation of magic and the Renaissance society. Also, I want to thank Professor Jung for reading the many versions of this dissertation and for providing a lot of helpful suggestions throughout the year. Secondly, I would like to thank The British Museum for giving me permission to use their highly detailed engravings, without which this dissertation would not exist. Thirdly, I would like to thank my boyfriend and my mother for supporting me, listening to my dilemmas and calming me down when stress got the better of me. Also, I want to thank my boyfriend for helping me track down the movies I needed for my analyses. Dekeyser ii Table of Contents Acknowledgments ....................................................................................................................... i List of Illustrations ................................................................................................................... -

J Ohn F. a Ndrews

J OHN F . A NDREWS OBE JOHN F. ANDREWS is an editor, educator, and cultural leader with wide experience as a writer, lecturer, consultant, and event producer. From 1974 to 1984 he enjoyed a decade as Director of Academic Programs at the FOLGER SHAKESPEARE LIBRARY. In that capacity he redesigned and augmented the scope and appeal of SHAKESPEARE QUARTERLY, supervised the Library’s book-publishing operation, and orchestrated a period of dynamic growth in the FOLGER INSTITUTE, a center for advanced studies in the Renaissance whose outreach he extended and whose consortium grew under his guidance from five co-sponsoring universities to twenty-two, with Duke, Georgetown, Johns Hopkins, North Carolina, North Carolina State, Penn, Penn State, Princeton, Rutgers, Virginia, and Yale among the additions. During his time at the Folger, Mr. Andrews also raised more than four million dollars in grant funds and helped organize and promote the library’s multifaceted eight- city touring exhibition, SHAKESPEARE: THE GLOBE AND THE WORLD, which opened in San Francisco in October 1979 and proceeded to popular engagements in Kansas City, Pittsburgh, Dallas, Atlanta, New York, Los Angeles, and Washington. Between 1979 and 1985 Mr. Andrews chaired America’s National Advisory Panel for THE SHAKESPEARE PLAYS, the BBC/TIME-LIFE TELEVISION canon. He then became one of the creative principals for THE SHAKESPEARE HOUR, a fifteen-week, five-play PBS recasting of the original series, with brief documentary segments in each installment to illuminate key themes; these one-hour programs aired in the spring of 1986 with Walter Matthau as host and Morgan Bank and NEH as primary sponsors. -

King and Country: Shakespeare’S Great Cycle of Kings Richard II • Henry IV Part I Henry IV Part II • Henry V Royal Shakespeare Company

2016 BAM Winter/Spring #KingandCountry Brooklyn Academy of Music Alan H. Fishman, Chairman of the Board William I. Campbell, Vice Chairman of the Board BAM, the Royal Shakespeare Company, and Adam E. Max, Vice Chairman of the Board The Ohio State University present Katy Clark, President Joseph V. Melillo, Executive Producer King and Country: Shakespeare’s Great Cycle of Kings Richard II • Henry IV Part I Henry IV Part II • Henry V Royal Shakespeare Company BAM Harvey Theater Mar 24—May 1 Season Sponsor: Directed by Gregory Doran Set design by Stephen Brimson Lewis Global Tour Premier Partner Lighting design by Tim Mitchell Music by Paul Englishby Leadership support for King and Country Sound design by Martin Slavin provided by the Jerome L. Greene Foundation. Movement by Michael Ashcroft Fights by Terry King Major support for Henry V provided by Mark Pigott KBE. Major support provided by Alan Jones & Ashley Garrett; Frederick Iseman; Katheryn C. Patterson & Thomas L. Kempner Jr.; and Jewish Communal Fund. Additional support provided by Mercedes T. Bass; and Robert & Teresa Lindsay. #KingandCountry Royal Shakespeare Company King and Country: Shakespeare’s Great Cycle of Kings BAM Harvey Theater RICHARD II—Mar 24, Apr 1, 5, 8, 12, 14, 19, 26 & 29 at 7:30pm; Apr 17 at 3pm HENRY IV PART I—Mar 26, Apr 6, 15 & 20 at 7:30pm; Apr 2, 9, 23, 27 & 30 at 2pm HENRY IV PART II—Mar 28, Apr 2, 7, 9, 21, 23, 27 & 30 at 7:30pm; Apr 16 at 2pm HENRY V—Mar 31, Apr 13, 16, 22 & 28 at 7:30pm; Apr 3, 10, 24 & May 1 at 3pm ADDITIONAL CREATIVE TEAM Company Voice -

The Statement

THE STATEMENT A Robert Lantos Production A Norman Jewison Film Written by Ronald Harwood Starring Michael Caine Tilda Swinton Jeremy Northam Based on the Novel by Brian Moore A Sony Pictures Classics Release 120 minutes EAST COAST: WEST COAST: EXHIBITOR CONTACTS: FALCO INK BLOCK-KORENBROT SONY PICTURES CLASSICS SHANNON TREUSCH MELODY KORENBROT CARMELO PIRRONE ERIN BRUCE ZIGGY KOZLOWSKI ANGELA GRESHAM 850 SEVENTH AVENUE, 8271 MELROSE AVENUE, 550 MADISON AVENUE, SUITE 1005 SUITE 200 8TH FLOOR NEW YORK, NY 10024 LOS ANGELES, CA 90046 NEW YORK, NY 10022 PHONE: (212) 445-7100 PHONE: (323) 655-0593 PHONE: (212) 833-8833 FAX: (212) 445-0623 FAX: (323) 655-7302 FAX: (212) 833-8844 Visit the Sony Pictures Classics Internet site at: http:/www.sonyclassics.com THE STATEMENT A ROBERT LANTOS PRODUCTION A NORMAN JEWISON FILM Directed by NORMAN JEWISON Produced by ROBERT LANTOS NORMAN JEWISON Screenplay by RONALD HARWOOD Based on the novel by BRIAN MOORE Director of Photography KEVIN JEWISON Production Designer JEAN RABASSE Edited by STEPHEN RIVKIN, A.C.E. ANDREW S. EISEN Music by NORMAND CORBEIL Costume Designer CARINE SARFATI Casting by NINA GOLD Co-Producers SANDRA CUNNINGHAM YANNICK BERNARD ROBYN SLOVO Executive Producers DAVID M. THOMPSON MARK MUSSELMAN JASON PIETTE MICHAEL COWAN Associate Producer JULIA ROSENBERG a SERENDIPITY POINT FILMS ODESSA FILMS COMPANY PICTURES co-production in association with ASTRAL MEDIA in association with TELEFILM CANADA in association with CORUS ENTERTAINMENT in association with MOVISION in association with SONY PICTURES -

Playing Shakespeare with Deutsche Bank Production of Twelfth Night

2016 shakespeare’s globe Annual review contents Welcome 5 Theatre: The Globe 8 Theatre: The Sam Wanamaker Playhouse 14 Celebrating Shakespeare’s 400th Anniversary 20 Globe Education – Inspiring Young People 30 Globe Education – Learning for All 33 Exhibition & Tour 36 Catering, Retail and Hospitality 37 Widening Engagement 38 How We Made It & How We Spent It 41 Looking Forward 42 Last Words 45 Thank You! – Our Stewards 47 Thank You! – Our Supporters 48 Who’s Who 50 The Playing Shakespeare with Deutsche Bank production of Twelfth Night. Photo: Cesare de Giglio The Little Matchgirl and Other Happier Tales. Photo: Steve Tanner WELCOME 2016 – a momentous year – in which the world celebrated the richness of Shakespeare’s legacy 400 years after his death. Shakespeare’s Globe is proud to have played a part in those celebrations in 197 countries and led the festivities in London, where Shakespeare wrote and worked. Our Globe to Globe Hamlet tour travelled 193,000 miles before coming home for a final emotional performance in the Globe to mark the end, not just of this phenomenal worldwide journey, but the artistic handover from Dominic Dromgoole to Emma Rice. A memorable season of late Shakespeare plays in the Sam Wanamaker Playhouse and two outstanding Globe transfers in the West End ran concurrently with the last leg of the Globe to Globe Hamlet tour. On Shakespeare’s birthday, 23 April, we welcomed President Obama to the Globe. Actors performed scenes from the late plays running in the Sam Wanamaker Playhouse at Southwark Cathedral, a service which was the only major civic event to mark the anniversary in London and was attended by our Patron, HRH the Duke of Edinburgh. -

Uvisno "Acting Is Handed on from Actor to Actor

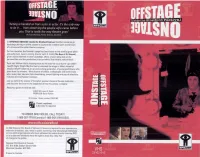

Inaide the Stratford Festival uviSNO "Acting is handed on from actor to actor. It's the only way to do it... from observing the people who came before you. That is really the way theatre goes" In OFFSTAGE ONSTAGE: Inside the Stratford Festival, Stratford cameras go backstage during an entire season to capture the creative spirit at the heart of a treasured Canadian theatre company. For five decades, the Festival's stage has been home to the world's great plays and performers. Award-winning director John N. Smith (The Boys of St. Vincent), given unprecedented access backstage, offers a fascinating look at the personalities and the production process behind live theatre performance. Peek into William Hutt's dressing room as he does his vocal warm-ups before Twelfth Night. Watch Martha Henry command the stage in Who's Afraid of Virginia Woolf? Observe an up-and-coming generation of young performers who learn from the masters. Meet dozens of artists, craftspeople and technicians who reveal their secrets, from shoemaking, sword fighting and sound effects to makeup and mechanical monkeys. Join us behind the scenes of Canada's premier classical theatre institution ... and discover the love for the stage that drives this artistic company. Resource guide on reverse side, DIRECTOR: John N. Smith PRODUCER: Gerry Flahive 83 minutes Order number: C9102 042 Closed captioned. A decoder is required. TO ORDER NFB VIDEOS, CALL TODAY! -800-267-7710 (Canada) 1-800-542-2164 (USA) © 2002 National Film Board of Canada. A licence is required for any reproduction, television broadcast, sale, rental or public screening. -

June 2016 President: Vice President: Simon Russell Beale CBE Nickolas Grace

No. 495 - June 2016 President: Vice President: Simon Russell Beale CBE Nickolas Grace Nothing like a Dame (make that two!) The VW’s Shakespeare party this year marked Shakespeare’s 452nd birthday as well as the 400th anniversary of his death. The party was a great success and while London, Stratford and many major cultural institutions went, in my view, a bit over-bard (sorry!), the VW’s party was graced by the presence of two Dames - Joan Plowright and Eileen Atkins, two star Shakespeare performers very much associated with the Old Vic. The party was held in the Old Vic rehearsal room where so many greats – from Ninette de Valois to Laurence Olivier – would have rehearsed. Our wonderful Vice-President, Nickolas Grace, introduced our star guests by talking about their associations with the Old Vic; he pointed out that we had two of the best St Joans ever in the room where they would have rehearsed: Eileen Atkins played St Joan for the Prospect Company at the Old Vic in 1977-8; Joan Plowright played the role for the National Theatre at the Old Vic in 1963. Nickolas also read out a letter from Ronald Pickup who had been invited to the party but was away in France. Ronald Pickup said that he often thought about how lucky he was to have six years at the National Theatre, then at Old Vic, at the beginning of his career (1966-72) and it had a huge impact on him. Dame Joan Plowright Dame Joan Plowright then regaled us with some of her memories of the Old Vic, starting with the story of how when she joined the Old Vic school in 1949 part of her ‘training’ was moving chairs in and out of the very room we were in. -

The Upstart Crow, Volume XXIX

Clemson University TigerPrints Upstart Crow (Table of Contents) Clemson University Press Fall 2010 The Upstart Crow, Volume XXIX Elizabeth Rivlin, Editor Clemson University Follow this and additional works at: https://tigerprints.clemson.edu/upstart_crow Recommended Citation Rivlin, Editor, Elizabeth, "The Upstart Crow, Volume XXIX" (2010). Upstart Crow (Table of Contents). 30. https://tigerprints.clemson.edu/upstart_crow/30 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Clemson University Press at TigerPrints. It has been accepted for inclusion in Upstart Crow (Table of Contents) by an authorized administrator of TigerPrints. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Vol_XXIX Clemson University Digital Press Digital Facsimile Vol_XXIX Shakesp ear ean Hearing guest edited by Leslie Dunn and Wes Folkerth Contents Essays Leslie Dunn and Wes Folkerth Editors’ Introduction to “Shakespearean Hearing” ....5 Erin Minear “A Verse to this Note”: Shakespeare’s Haunted Songs .................... 11 Kurt Schreyer “Here’s a knocking indeed!” Macbeth and the Harrowing of Hell ... 26 Paula Berggren Shakespeare and the Numbering Clock ..........................................44 Allison Kay Deutermann “Dining on Two Dishes”: Shakespeare, Adaptation, and Auditory Reception of Purcell’s Th e Fairy-Queen ..................................... 57 Michael Witmore Shakespeare’s Inner Music ................................................. 72 Performance Reviews Michael W. Shurgot and Peter J. Smith Th e 2010 Season at London’s Globe Th eatre .........................................................................................................83 Sara Th ompson Th e Royal Shakespeare Company 2009:As You Like It ............. 99 Owen E. Brady Th e 2009 Stratford Festival:Macbeth and Bartholomew Fair ..103 Michael W. Shurgot Th e 2009 Oregon Shakespeare Festival ..............................111 Bryan Adams Hampton Th e 2010 Alabama Shakespeare Festival:Hamlet .....