The Death of Me

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

To Reformative Theory of Punishment”

“AN EYE FOR AN EYE WILL TURN THE WHOLE WORLD BLIND - IN SPECIAL CONTEXT TO REFORMATIVE THEORY OF PUNISHMENT” Rustam Singh Thakur1 “An eye for an eye will turn the whole world blind” – Mahatma Gandhi2, This line by Mahatma Gandhi is the thrust of the Reformative Theory of Punishment . The most recent and the most humane of all theories are based on the principle of reforming the legal offenders through individual treatment. Not looking to criminals as inhuman this theory puts forward the changing nature of the modern society where it presently looks into the fact that all other theories have failed to put forward any such stable theory, which would prevent the occurrence of further crime3. Reform in the deterrent sense implied that through being punished the offender recognized his guilt and wished to change. This theory aims at rehabilitating the offender to the norms of the society i.e. into law-abiding member. This theory condemns all kinds of corporal punishments4. Though this theory works stupendously for the correction of juveniles and first time criminals, but in the case of a hardened criminal this theory may not work with the effectiveness5. A Prolegomenon “Crime is behaviour or action that is punishable by criminal law. A crime is a public wrong, as opposed to a moral, wrong; it is an offence committed against (and hence punishable by) the state or the community at large. Many crimes are immoral, but not all actions considered immoral are illegal.”6 According to Durkheim, “crime exists in every society which do and do not have laws, courts and the police. -

Report of Activities 2007-08 C

28 Eklavya: Report of Activities 2007-08 C. Publication Programme C.1 Development and Editorial C.1.1 Chakmak Chakmak is a magazine for children (8 to 14 years) and has been published since 1985. Over the years Chakmak has helped to vastly diversify and enrich children’s literature in Hindi, and to induce leading writers and illustrators to write and illustrate for children. Above all, it has had a great success in motivating the children themselves to write, draw and get published. However, we had been feeling for some time that it had fallen into a stereotype and needed to break out of it. So this year Chakmak took a break for about seven months (April to October) and the time was used to reconceptualise and redesign it so as to give it a contemporary look and feel. A large number of people, both experts on children’s literature and ordinary readers, reviewed Chakmak and helped to mould the direction of change. A two-day review workshop was held involving senior litterateurs, science writers, designers etc. It was noted in this workshop that Chakmak had Eklavya: Report of Activities 2007-08 29 always carried material which tried to make children more sensitive towards their environment, enhanced their creativity, and developed an analytic vision in them. The challenge was to also make it appropriate, attractive and meaningful for today’s readers. It was strongly recommended that Chakmak should have a new look, both in terms of content and design. The need for more original writing presented in an attractive fashion, and diversity in content was greatly emphasized. -

TEQIP-II ACTIVITY CALENDAR July-Dec 2013 Volume I, Issue 2

Guru Nanak Dev Engineering College, Ludhiana An Autonomous College under UGC Act - 1956 [2(f) and 12(B)] TEQIP-II ACTIVITY CALENDAR July-Dec 2013 Volume I, Issue 2 Director : Dr. M. S. Saini www.gndec.ac.in TEQIP Coordinator : Dr. J.N. Jha Nearly 15,000 graduate and 3500 Post Graduate Engineers About TEQIP-II have passed out from this college during the last 57 years Introduction: and are at present successfully employed in India & abroad. The College has also been identified as First QIP Centre of Technical Education Quality Improvement Programme Punjab by All India council for Technical Education (TEQIP) was envisaged as a long-term programme of about (AICTE) for Ph.D Programme and is one among the 10-12 years duration to be implemented in 2-3 phases for existing 42 QIP Centres including IITs at National Level. In transformation of the Technical Education System with the last five years, the faculty has published around 225 research World Bank assistance. papers in National/Internal Journals and more than 450 papers in various conferences in India and abroad. Around As per TEQIP design, each phase is required to be designed 25 teachers have attended International conferences and on the basis of lessons learnt from the implementation of an other interactions under DST/AICTE/PTU travel grant earlier phase. TEQIP-I started a reform process in 127 program. More than 40% teachers are having Ph.D degree Institutions. The reform process needs to be sustained and and another 40% teachers are pursuing Ph.D. 35 Research scaled-up for embedding gains in the system and taking the projects, Seminar Grants and STTPs have been granted by transformation to a higher level. -

Liste Des Livres Et Tirés-À-Part Disponibles Au Club

Liste des livres et tirés-à-part disponibles au Club Auteur Titre Date Etagère Cote ACHCAR Gilbert Le Peuple veut: une exploration radicale du soulèvement arabe 2013 Conférences CLUB/STA ADAM Véronique CAIOZZO Anna dir. (chapitre La fabrique du corps humain: la machine modèle du vivant Promotion 2009 CLUB/STA de ZAPPERI Giovanna) AGLIETTA Michel Un New deal pour l'Europe 2013 Conférences CLUB/STA AGLIETTA Michel Sortir de la crise et inventer l'avenir 2014 Conférences CLUB/AGL AHMED SALEM Zekeria Islam politique et changement social en Mauritanie 2013 Promotion 2012-2013 CLUB/2012-13/AHM AHMED SALEM Zekeria Ould Les Trajectoires d'un Etat-frontière. Espaces, évolution politique et transformations sociales en Mauritanie 2011 Promotion 2012-2013 IEA/SAL AKAKPO Yaovi Nunya, N° 2, Décembre 2014. Imagination et Univers de sens. 2014 Instances IEA CLUB/AKA AKAKPO Yaovi Nunya, N° 2, Décembre 2014. Imagination et Univers de sens. 2014 Instances IEA CLUB/AKA AKANDJI-KOMBE Jean-François Egalité et droit social. (Les rencontres sociales de la Sorbonne, Volume 2.) 2014 Promotion 2016-2017 CLUB/2016-17/AKAN AKHILESH AAP-BEETI Biography of Marc Chagall translation in Hindi 2010 Promotion 2011-2012 CLUB/2011-12/AKH AKHILESH ACHAMBHE KA RONA. Essay on art and artists 2010 Promotion 2011-2012 CLUB/2011-12/AKH AKHILESH AKHILIESH: EK SAMVADD (Dialogue on my art with poet Piyush Daiya) 2010 Promotion 2011-2012 CLUB/2011-12/AKH AKHILESH MAQBOOL . A biography of noted indian painter. First edition 2010 Promotion 2011-2012 CLUB/2011-12/AKH AKHILESH MAQBOOL. Second edition 2010 Promotion 2011-2012 CLUB/2011-12/AKH AKHILESH DARASPOTHI. -

Kabbalah, Magic & the Great Work of Self Transformation

KABBALAH, MAGIC AHD THE GREAT WORK Of SELf-TRAHSfORMATIOH A COMPL€T€ COURS€ LYAM THOMAS CHRISTOPHER Llewellyn Publications Woodbury, Minnesota Contents Acknowledgments Vl1 one Though Only a Few Will Rise 1 two The First Steps 15 three The Secret Lineage 35 four Neophyte 57 five That Darkly Splendid World 89 SIX The Mind Born of Matter 129 seven The Liquid Intelligence 175 eight Fuel for the Fire 227 ntne The Portal 267 ten The Work of the Adept 315 Appendix A: The Consecration ofthe Adeptus Wand 331 Appendix B: Suggested Forms ofExercise 345 Endnotes 353 Works Cited 359 Index 363 Acknowledgments The first challenge to appear before the new student of magic is the overwhehning amount of published material from which he must prepare a road map of self-initiation. Without guidance, this is usually impossible. Therefore, lowe my biggest thanks to Peter and Laura Yorke of Ra Horakhty Temple, who provided my first exposure to self-initiation techniques in the Golden Dawn. Their years of expe rience with the Golden Dawn material yielded a structure of carefully selected ex ercises, which their students still use today to bring about a gradual transformation. WIthout such well-prescribed use of the Golden Dawn's techniques, it would have been difficult to make progress in its grade system. The basic structure of the course in this book is built on a foundation of the Golden Dawn's elemental grade system as my teachers passed it on. In particular, it develops further their choice to use the color correspondences of the Four Worlds, a piece of the original Golden Dawn system that very few occultists have recognized as an ini tiatory tool. -

Anaemia and Body Mass Index (BMI) of Fisherwomen Inhabiting in Karang Island of Loktak Lake, Manipur (India)

Eurasian Journal of Anthropology Euras J Anthropol 3(2):47−53, 2012 Anaemia and body mass index (BMI) of fisherwomen inhabiting in Karang island of Loktak Lake, Manipur (India) Maishnam Rustam Singh, Karnajit Mangang2 2Department of Anthropology, Manipur University, Manipur, India Received December 3, 2012 Accepted February 5, 2013 Abstract The paper examines the status of anaemia and body mass index (BMI) among fisherwomen of Karang Island Village, Manipur, India. Altogether 180 Meitei fisherwomen of age group 15 to 49 years were chosen for the study. Two anthropometric measurements viz., stature and body weight were taken on each subject. For estimation of haemoglobin level two standard methods namely, haemoglobin colour scale (HCS) and Sahli’s haemoglobinometer were employed. About 70% of the fisherwomen of Karang village are in normal BMI category, while 16 % of them are underweight, 11 % overweight and 3 % obese. The prevalence of anaemia is notably high among the fisherwomen of this village with a frequency of 68.89%. Women with normal BMI and non-anaemic constitute 24.44%. The mean values of haemoglobin concentration measured by HCS and Sahli’s method is 10.82gm/dl and 10.94gm/dl respectively. The two mean values were tested for t-test of significance and found statistically insignificant (t=0.852). The two adopted methods for haemoglobin estimation viz., HCS and Sahli’s method are found reliable. The correlation value of BMI and haemoglobin level shows negative in association (r = 0.060) and the value is found insignificant (t=0.566). The insignificance of this relationship means there is no correlation. -

Nero Numero 0

questo primo numero è dedicato a Emiliana Mensile a distribuzione gratuita Direttore Responsabile Giuseppe Mohrhoff 02 / RUSS MEYER Direzione 05 / ANOMOLO RECORDS Francesco de Figueiredo 08 / MELTING & DISTINGUISHING ([email protected]) Luca Lo Pinto 10 / CONTEMP/OLACCHI ([email protected]) Valerio Mannucci 12 / RAYMOND SCOTT ([email protected]) Lorenzo Micheli Gigotti 15 / PARIS-DABAR ([email protected]) 16 / OLAF NICOLAI Collaboratori 19 / ENDOGONIDIA Francesco Tato’ 23 / CESARE PIETROIUSTI / Rosso Ilaria Gianni Rudi Borsella 27 / WAKING LIFE Francesco Ventrella Carola Bonfili 30 / ACCUMULAZIONI > DISPERSIONI Anna Passarini Edoardo Caruso 32 / JUSTIN BENNETT Paolo Colasacco Nicola Capodanno 35 / ARCHIGRAM Andrea Proia Anna Neudecker 37 / WIRE Marco Cirese Marta Garzetti 40 / TORE SANSONETTI Edgardo Ferrati 42 / NERO TAPES Progetto Grafico e Impaginazione Industrie Grafiche di Roma 43 / RICCARDO PREVIDI / Supercolosseo 2004 Daniele De Santis ([email protected]) 44 / RECENSIONI Pubblicita’ 48 / NERO INDEX [email protected] 06/97600104 339/7825906 339/1453359 Distribuzione [email protected] 333/6628117 333/2473090 Editore Produzioni NERO soc. coop. a r.l NERO Numero 1 Via Paolo V, 53 00168 ROMA tel. 06/97600104 - [email protected] www.neromagazine.it registrazione al tribunale di Roma n. 102/04 del 15 marzo 2004 Stampa OK PRINT Via Calamatta, 16 - ROMA In copertina un’illustrazione di Carola Bonfili ogni erotomane assillato dall’abbondanza godereccia e sbavona dei seni gonfi, grossi e fecondi. Erotismo e violenza, spirito di sopraffazione tra sessi e ironia, prorompenti pin-up e reietti sociali sono miscelati all’interno di vicende narrative sconclusionate e RUSS MEYER demenziali. di Lorenzo Micheli Gigotti Quello di Russ Meyer è uno sguardo provocatorio “Signori e signore benvenuti alla violenza. -

Sadguru Drishti July-Sept. 2017

Param Pujya Gurudev Shri Ranchhoddasji Maharaj Sadguru Drishti July-Sept. 2017 1 YOUNG ACHIEVER AWARD -- 5th - 6th AUGUST Dr. Gautam Singh Parmar, Head of Department, Cornea, Sadguru Netra Chikitsalaya, Shri Sadguru Seva Sangh Trust, Chitrakoot received Young Achiever Award by Shri. Harshvardhanji, minister for Science and Technology, Government of India, on the occasion of ISCKRS ( Indian society of Cornea and keratorefractive Surgeons) annual conference held at New Delhi on August 5th and 6th, 2017 LIFE TIME ACHIEVEMENT AWARD – 23rd SEPTEMBER It is indeed a proud moment as Dr. B. K. Jain, Trustee & Director of Shri Sadguru Seva Sangh Trust, Chitrakoot was presented with ‘The Life Time Achievement Award’ at the Intraocular Implant & Refractive Society of India (IIRSI) - Annual Conference, New Delhi on September 23, 2017. From the latest innovation to the challenges, the scientific committee of the IIRSI honours people who have contributed immensely in the field of Ophthalmology. Dr. B.K. Jain has made various presentations and papers in the said field. He has also introduced community outreach eye camps, vision centers and operational research in Central India. His vision to put Sadguru Netra Chikitsalaya on the global map of eye care providers truly makes him deserving of the award. Our heartiest congratulations from the entire family of Shri Sadguru Seva Sangh Trust. 2 CHIEF MINISTER’S VISIT -- 10th SEPTEMBER Shri Shivraj Singh Chouhan, Chief Minister of Madhya Pradesh visited Sadguru Netra Chikitsalaya, Shri Sadguru Seva Sangh Trust (SSSST), Chitrakoot on 10th September, 2017. Dr. B.K. Jain, Director and Trustee of SSSST showcased the activities undertaken by the trust to the Chief Minister who appreciated the contributions and assured full co-operation by the State Govt. -

Merchandise ARTIST: Dillinger Escape Plan

Last Update: 11/03/10 ARTIST: Dillinger Escape Plan TITLE: Darkness Limited Edition Custom Zip Hoodie Black (L) Label: AON/Atlantic Off-Roster Non-Music Config & Selection #: MH 501011 L Street Date: 11/02/10 Order Due Date: 10/13/10 UPC: 075678900211 ALTERNATE VIEW Box Count: 12 Unit Per Set: 1 SRP: $60 Alphabetize Under: D For the latest up to date info on Merchandise OTHER SIZES: this release visit WEA.com. MH:075678900198 Darkness Limited Edition Custom Zip Hoodie Black (2X)($61) MH:075678900235 Darkness Limited Edition Custom Zip Hoodie Black (S)($60) MH:075678900204 Darkness Limited Edition Custom Zip Hoodie Black (XL)($60) MH:075678900228 Darkness Limited Edition Custom Zip Hoodie Black (M)($60) AVAILABLE MERCH DESIGN Silver Ink Flag T-Shirt Ribbit Slim Fit T-shirt Silver ALBUM FACTS Genre: Rock Description: This custom limited edition hoodie is from Christian Hanson's team at Thunderware. It is made from a medium weight material and includes the imprint of their latest album, Option Paralysis in the hood, as well as a sleek iPod/iPhone pocket on the sleeve. ARTIST & INFO From their early days in the late-'90s as short-haired Rutgers, New Jersey, college students delivering hyper-complex thrash to audiences of boorish long-haired surly metalheads, to performing with Nine Inch Nails on the pioneering electronic band's farewell shows, the Dillinger Escape Plan have merely one prerogative: to go forward in ALL directions simultaneously. Their groundbreaking 1999 debut full-length, Calculating Infinity, is inarguably the essential technical-metal talisman for the 21st century, melding hardcore's blinding rage with a musical vision that made most progressive-rock bands sound positively lazy by comparison. -

In the Supreme Court of India Civil Appellate Jurisdiction

1 REPORTABLE IN THE SUPREME COURT OF INDIA CIVIL APPELLATE JURISDICTION CIVIL APPEAL NOS. 3681-3682 OF 2020 (Arising out of SLP (C) Nos. 21326-21327 OF 2019) Rattan Singh & Ors. ¼ Appellants Versus Nirmal Gill & Ors. etc. ¼Respondents WITH CIVIL APPEAL NOS. 3683-3684 OF 2020 (Arising out of SLP (C) Nos. 29775-29776 OF 2019) Inder Pal Singh & Anr. ¼ Appellants Versus Nirmal Gill & Ors. etc. ¼Respondents J U D G M E N T A.M. Khanwilkar, J. 1. Leave granted. 2. These appeals take exception to the common Judgment and decree of the High Court of Punjab and Haryana at Chandigarh1, dated 27.05.2019 in R.S.A. Nos. 2901/2012 and 3881/2012, 1 for short, “the High Court” 2 whereby the High Court reversed the concurrent findings of the trial Court and the first appellate Court and decreed the suits of the plaintiff. 3. For convenience, the parties are referred to as per their status in Civil Suit No. 11/2001 before the Court of Civil Judge (Senior Division), Hoshiarpur2. The admitted factual position in the present cases is that one Harbans Singh had married Gurbachan Kaur and fathered Joginder Kaur (plaintiff ± now deceased) in the wedlock. After the demise of Gurbachan Kaur, Harbans Singh married Piar Kaur and in that wedlock, he fathered Gurdial Singh (defendant No. 3), Rattan Singh (defendant No. 4), Narinder Pal Singh (defendant No. 5) and Surjit Singh (defendant No. 6). Harcharan Kaur (defendant No. 1) is the wife of defendant No. 4 and the step sister-in-law of the plaintiff. -

The Dillinger Escape Plan Irony Is a Dead Scene Mp3, Flac, Wma

The Dillinger Escape Plan Irony Is A Dead Scene mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Rock Album: Irony Is A Dead Scene Country: US Released: 2002 Style: Math Rock, Hardcore MP3 version RAR size: 1524 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1127 mb WMA version RAR size: 1227 mb Rating: 4.4 Votes: 361 Other Formats: MIDI AU AA WMA AC3 AIFF MP4 Tracklist Hide Credits A1 Hollywood Squares A2 Pig Latin B1 When Good Dogs Do Bad Things Come To Daddy B2 Written-By – Richard D. James Credits Bass – Liam Wilson Drums, Percussion, Keyboards – Chris Pennie Engineer – Chris Badami Guitar – Brian Benoit Guitar, Keyboards – Benjamin Weinman Keyboards, Sampler – Adam Doll Mastered By – Alan Douches Mixed By – Steve Evetts Producer – Benjamin Weinman, Chris Pennie, Mike Patton Voice, Sampler, Percussion – Mike Patton Written-By – Mike Patton (tracks: A1 to B1), The Dillinger Escape Plan (tracks: A1 to B1) Notes Original pressing on orange transparent vinyl with black mix. Unknown copies made. One of a kind copy, or perhaps a few out of 100 orange copies got some black color mixed in from the black vinyl pressing. Release labels incorrectly state this record plays at 45rpm, however it plays at 33⅓rpm. Record housed in a PVC sleeve with printed paper insert serving as the front cover. with s fold creating a small flap which serves as the rear sleeve containing all release information. © & ℗ 2002. Manufactured and distributed by Lookout! Records. Barcode and Other Identifiers Barcode: 763361981110 Matrix / Runout (Hand-etched Runout Side A): BH-011-A "TOM WANTED -

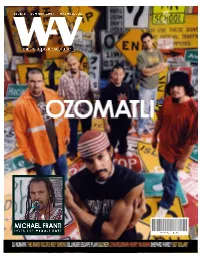

WAV / Kotori Magazine Issue 2 Ozomatli Michael Franti DJ Numark the Mars Volta's Ikey Owens Dillinger

Serrated Intellect jason mascow We’re coming closer and closer to one of the most important days of the rest of our lives. i know you’re probably sick and tired of hearing it by now, but it’s something we’ve just got to suck up. I mean, letz face it, there’s a hell of a reason to. November 2, 2004. Election day. I hate to introduce WAV magazine’s long-awaited second issue with a topic sure to elicit more jeer than cheer, but I trust you can respect itz immediacy. Immediacy that has prompted the artists and personalities we love, hate, and admire, to dedicate a good chunk of their obligation to. Of the countless events we attended over the past few years, there has existed at least a brief moment, often times full-on ‘speeches,’ dedicated to speaking up against the direction our beautiful, once- not-too-long-ago respected country is headed. And they do it out of pure passion and heartfelt belief, many times angering the businesses, marketers, government, corporations, sponsors…basically the money… behind them. and wasn’t that the idea in the first place? scare us into thinking that the only right way was their way? But still, the artists feel they just have to. After seeing a steady stream of this at just about every club I walked into, every festival lawn I frolicked on, every stage, theater, and coffeehouse I visited, I realized that i was not alone…and with this empowerment, I started to become less and less afraid.