Rescued from Oblivion

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Parish Staff Pastor Rev

Parish Staff Pastor Rev. David Powers Sch.P. Parochial Vicars Rev. Nelson Henao Sch.P. Rev. Richard Wyzykiewicz Sch.P. Parish Secretary Mrs. Rosemarie Ortiz Organist Mr. Franco Bonanome Leader of Song Mrs. Terry Bonanome January-February, 2016 saint Director of Development Mrs. Stephanie Turtle Helena St. Helena’s School (718) 892-3234 parish Early Childhood (3-4 year olds) Elementary School (Grades K-8) Bronx, NY Principal: Mr. Richard Meller Mass Schedule 2050 Benedict Avenue Bronx, New York 10462 High School: Monsignor Scanlan H.S. (718) 430-0100 http://www.scanlanhs.edu/ Principal: Mr. Peter Doran 915 Hutchinson River Parkway Bronx, New York 10465 made at St. Helena Rectory: Certificate. 1315 Olmstead Avenue Bronx, N.Y. 10462 should Phone: (718) 892-3232 as as at the Rectory. Fax: (718) 892-7713 a www.churchofsthelena.com Email: [email protected] at Rectory. Alumni: [email protected] ST. L BRONX, A WORD FROM THE PASTOR: St. Thomas as pride, avarice, gluttony, lust, sloth, envy, and NEWSFLASH - SIN DOES EXIST—PART 3 anger. Many people ask: Today, we seem to have lost a sense of sin. All systems, religious Is it possible to sin and not be aware that one has done so? and ethical, which either deny, on the one hand, the existence of a personal creator and lawgiver distinct from and superior to his The answer is “yes” because there is a distinction between the creation, or, on the other, the existence of free will and objective elements (object itself and circumstances) and the responsibility in man, distort or destroy the true biblico-theological subjective (advertence to the sinfulness of the act). -

PRESS DOSSIER the Ommegang of Brussels Is Now Inscribed on UNESCO's Representative List of the Intangible Cultural Heritage A

PRESS DOSSIER The Ommegang of Brussels is now inscribed on UNESCO’s Representative List of the Intangible Cultural Heritage A little bit of history... The Ommegang of Brussels takes place in the centre of Brussels every year at the start of July. In old Flemish, “Ommegang” means “circumambulation”, the act of walking around. It was the name once given to the procession by the Guild of Crossbowmen in honour of Our Lady of Sablon, a legendary virgin who arrived from Antwerp on a barge and was placed under the protection of the crossbowmen, defenders of the medieval city. That procession followed a route between the Chapel of the Guild of Crossbowmen in the Sablon/Zavel and the Grand Place/Grote Markt. Over time, the different sectors of society in the city joined the procession, which became so representative of Brussels that it was presented to Charles V and his son Philip on 2 June 1549. The Ommegang and the majority of its participants disappeared in the 18th century with the ending of the Ancien Régime. In 1930, to celebrate the centenary of the Kingdom of Belgium, the procession was revived by the will of the guilds of crossbowmen, the historian Albert Marinus and the political and religious authorities of Brussels. This modern Ommegang was recreated based on the descriptions of the procession that Charles V attended in 1549. Ever since, it perpetuates the tradition of processions of the former Brabant, which included corporate nations, lineages, magistracy, rhetoric chambers, the clergy, dancers, musicians, jesters, processional giants and animals and often the figure of Charles V. -

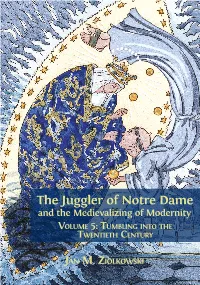

The Juggler of Notre Dame and the Medievalizing of Modernity VOLUME 5: TUMBLING INTO the TWENTIETH CENTURY

The Juggler of Notre Dame and the Medievalizing of Modernity VOLUME 5: TUMBLING INTO THE TWENTIETH CENTURY JAN M. ZIOLKOWSKI THE JUGGLER OF NOTRE DAME VOLUME 5 The Juggler of Notre Dame and the Medievalizing of Modernity Vol. 5: Tumbling into the Twentieth Century Jan M. Ziolkowski https://www.openbookpublishers.com © 2018 Jan M. Ziolkowski This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license (CC BY 4.0). This license allows you to share, copy, distribute and transmit the work; to adapt the work and to make commercial use of the work providing attribution is made to the author (but not in any way that suggests that he endorses you or your use of the work). Attribution should include the following information: Jan M. Ziolkowski, The Juggler of Notre Dame and the Medievalizing of Modernity. Vol. 5: Tumbling into the Twentieth Century. Cambridge, UK: Open Book Publishers, 2018, https://doi.org/10.11647/OBP.0148 Copyright and permissions for the reuse of many of the images included in this publication differ from the above. Copyright and permissions information for images is provided separately in the List of Illustrations. Every effort has been made to identify and contact copyright holders and any omission or error will be corrected if notification is made to the publisher. In order to access detailed and updated information on the license, please visit https://www. openbookpublishers.com/product/821#copyright Further details about CC BY licenses are available at http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ All external links were active at the time of publication unless otherwise stated and have been archived via the Internet Archive Wayback Machine at https://archive.org/web Digital material and resources associated with this volume are available at https://www.openbookpublishers. -

Of a Princely Court in the Burgundian Netherlands, 1467-1503 Jun

Court in the Market: The ‘Business’ of a Princely Court in the Burgundian Netherlands, 1467-1503 Jun Hee Cho Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY 2013 © 2013 Jun Hee Cho All rights reserved ABSTRACT Court in the Market: The ‘Business’ of a Princely Court in the Burgundian Netherlands, 1467-1503 Jun Hee Cho This dissertation examines the relations between court and commerce in Europe at the onset of the modern era. Focusing on one of the most powerful princely courts of the period, the court of Charles the Bold, duke of Burgundy, which ruled over one of the most advanced economic regions in Europe, the greater Low Countries, it argues that the Burgundian court was, both in its institutional operations and its cultural aspirations, a commercial enterprise. Based primarily on fiscal accounts, corroborated with court correspondence, municipal records, official chronicles, and contemporary literary sources, this dissertation argues that the court was fully engaged in the commercial economy and furthermore that the culture of the court, in enacting the ideals of a largely imaginary feudal past, was also presenting the ideals of a commercial future. It uncovers courtiers who, despite their low rank yet because of their market expertise, were close to the duke and in charge of acquiring and maintaining the material goods that made possible the pageants and ceremonies so central to the self- representation of the Burgundian court. It exposes the wider network of court officials, urban merchants and artisans who, tied by marriage and business relationships, together produced and managed the ducal liveries, jewelries, tapestries and finances that realized the splendor of the court. -

Saint Augustine Catholic Church Upon the Death of Bishop Floyd L

St. Augustine Parish, Oakland California Twenty-First Sunday of Ordinary Time August 21st 2016 Twenty-First Sunday of Ordinary Time August 21st, 2016 Continued from page 1 Saint Augustine Catholic Church Upon the death of Bishop Floyd L. Begin, founding bishop of the Diocese of Oakland, Bishop Cummins was appointed the second Bishop of Oakland and installed on June 30, 1977. He retired in 2003. “Vatican II, Berkeley and Beyond: The First Half-Century of the Oakland Diocese, 1962-2012,” is the memoir writ- Parish Feast ten by Bishop Cummins. It is available at the Cathedral shop and on Amazon.com. On August 28th we celebrate the feast of Saint Augustine of Father Augustine Hippo (354 - 430), the patron saint of our parish. He was the bishop of Hippo in North Africa (Algeria). Feast of Pope St. Pius X, August 21st Saint Augustine is one of the seminal minds of the early Church and wrote extensively on topics related to Christian Pope Saint Pius X (Italian: Pio X) born Giuseppe Melchiorre Sarto,[a] (2 June 1835 – 20 August 1914), was Pope from doctrine: Trinity, divine grace, evil, original sin, etc. His August 1903 to his death in 1914. He was canonized in 1954. Pius X is known for vigorously most popular book has been, “Confessions,” which is consid- opposing modernist interpretations of Catholic doctrine, promoting traditional devotional practices and orthodox ered a spiritual classic and read by a lot of people, even to theology. His most important reform was to order the codification of the first Code of Canon Law, which collected the this day. -

Welcome to the World of Visions Educational Travel. Outstanding

Tour: Roman Pilgrimage: A Culture & Faith Tour Destination: Rome & Pompeii, Italy Availability: Year-round Roman Pilgrimage - Sample Itinerary A Culture & Faith Tour Day Morning Afternoon Evening Time Elevator: 1 Travel to Rome by flight, transfer to Hotel; check-in and relax Dinner at Hotel History of Rome 2 Breakfast Ancient Rome Guided Tour: Coliseum, Roman Forum & Palatine Hill Gladiator School* Dinner at Hotel 3 Breakfast Guided Tour: Vatican Museums, Sistine Chapel, St. Peter's Basilica & Castel Sant'Angelo Pizza Cooking Class* 4 Breakfast Guided Walking Tour of Naples & Naples Underground Guided Tour of Pompeii Dinner at Hotel Attend Mass at Local Saint John Lateran Basilica & The The Roman Ghost & Mystery 5 Breakfast Dinner at Hotel Roman Chapel Basilica of Saint Mary Major Catacombs Tour* 6 Breakfast Guided Tour: Ostia Antica Guided Walking Tour: Baroque Rome Dinner at Hotel 7 Breakfast Transfer to airport; fly home * Indicates activities that may be added on at extra cost, per your request Welcome to the world of Visions Educational Travel. Outstanding destinations filled with history, humanities, and a world outside of the classroom brought to you as only Visions can! As with all sample itineraries, please be aware that this is an “example” of a schedule and that the activities included may be variable dependent upon dates, weather, special requests and other factors. Itineraries will be confirmed prior to travel. Rome…. Modern and old, past and present go side by side; all the time. You can decide to follow the typical paths or you can be lucky enough to go off the usual tracks. -

Isabel Clara Eugenia and Peter Paul Rubens’S the Triumph of the Eucharist Tapestry Series

ABSTRACT Title of Document: PIETY, POLITICS, AND PATRONAGE: ISABEL CLARA EUGENIA AND PETER PAUL RUBENS’S THE TRIUMPH OF THE EUCHARIST TAPESTRY SERIES Alexandra Billington Libby, Doctor of Philosophy, 2013 Directed By: Professor Arthur K. Wheelock, Jr., Department of Art History and Archeology This dissertation explores the circumstances that inspired the Infanta Isabel Clara Eugenia, Princess of Spain, Archduchess of Austria, and Governess General of the Southern Netherlands to commission Peter Paul Rubens’s The Triumph of the Eucharist tapestry series for the Madrid convent of the Descalzas Reales. It traces the commission of the twenty large-scale tapestries that comprise the series to the aftermath of an important victory of the Infanta’s army over the Dutch in the town of Breda. Relying on contemporary literature, studies of the Infanta’s upbringing, and the tapestries themselves, it argues that the cycle was likely conceived as an ex-voto, or gift of thanks to God for the military triumph. In my discussion, I highlight previously unrecognized temporal and thematic connections between Isabel’s many other gestures of thanks in the wake of the victory and The Triumph of the Eucharist series. I further show how Rubens invested the tapestries with imagery and a conceptual conceit that celebrated the Eucharist in ways that symbolically evoked the triumph at Breda. My study also explores the motivations behind Isabel’s decision to give the series to the Descalzas Reales. It discusses how as an ex-voto, the tapestries implicitly credited her for the triumph and, thereby, affirmed her terrestrial authority. Drawing on the history of the convent and its use by the king of Spain as both a religious and political dynastic center, it shows that the series was not only a gift to the convent, but also a gift to the king, a man with whom the Infanta had developed a tense relationship over the question of her political autonomy. -

The Church in the Post-Tridentine and Early Modern Eras

Provided by the author(s) and NUI Galway in accordance with publisher policies. Please cite the published version when available. Title The Church in the Tridentine and Early Modern Eras Author(s) Forrestal, Alison Publication Date 2008 Publication Forrestal, Alison, The Church in the Tridentine and Early Information Modern Eras In: Mannion, G., & Mudge, L.S. (2008). The Routledge Companion to the Christian Church: Routledge. Publisher Routledge Link to publisher's https://www.routledge.com/The-Routledge-Companion-to-the- version Christian-Church/Mannion-Mudge/p/book/9780415567688 Item record http://hdl.handle.net/10379/6531 Downloaded 2021-09-26T22:08:25Z Some rights reserved. For more information, please see the item record link above. The Church in the Tridentine and Early Modern Eras Introduction: The Roots of Reform in the Sixteenth Century The early modern period stands out as one of the most creative in the history of the Christian church. While the Reformation proved viciously divisive, it also engendered theological and devotional initiatives that, over time and despite resistance, ultimately transformed the conventions of ecclesiology, ministry, apostolate, worship and piety. Simultaneously, the Catholic church, in particular, underwent profound shifts in devotion and theological thought that were only partially the product of the shock induced by the Reformation and at best only indirectly influenced by pressure from Protestant Reformers. Yet despite the pre-1517 antecedents of reformatio, and the reforming objectives of the Catholic Council of Trent (1545-7, 1551-2, 1562-3), the concept of church reform was effectively appropriated by Protestants from the sixteenth century onwards. Protestant churchmen claimed with assurance that they and the Reformation that they instigated sought the church’s 'reform in faith and practice, in head and members’. -

Saint Ambrose Catholic Church

Saint Ambrose Catholic Church Pastor Rev. Steven Zehler 904-692-1366, ext. 3 [email protected] Weekend Mass Schedule Saturday Vigil 5:00pm Sunday 9:00am and 11:00am Daily Mass Schedule M,T,F 8:00am Wednesday 6:00pm Thursday 9:00am Confessions Saturday 4:00 – 4:30pm Wednesday 5:00 – 5:30pm Church Staff Office Manager: Terri Sowards Office Assistant: Marybeth Gaetano Religious Ed. Coordinator: Christine Humphries Music Director: Tom Rivers Youth Ministry Coordinator: Chris Fisk Office Hours Monday – Thursday 9:00am to 2:00pm Church Address 6070 Church Rd. August 22, 2021 | Twenty-First Sunday in Ordinary Time Elkton, FL 32033 Office: 904-692-1366 Year of Saint Joseph Fax: 904-692-1136 choffice1@saintambrose- Living the Gospel of Jesus Christ church.org in the Catholic tradition since 1875 saintambrose-church.org Ministry Contact List Altar Servers: Parish Office 904-692-1366 First Friday Eucharistic Adoration Fair Chairman: Frank DuPont 904-814-2276 Friday, September 3 Finance Council: Larry Clark [email protected] Music Director: Tom Rivers [email protected] 9:00 am - 7:00 pm Office Manager: Terri Sowards [email protected] Office Assistant: Marybeth Gaetano [email protected] Saint Ambrose Parish Calendar Youth Ministry Coordinator: Chris Fisk [email protected] Monday, August 23 Pastoral Council: Nancy Dupont, Church Office 904-692-1366 8:00 am Morning Mass Intention: Lucy & George Olczak (SI) Prayer List: Donna Rogero [email protected] 386-325-5230 RCIA: Parish Office 904-692-1366 Tuesday, August 24 Respect Life: Ana Martin 904-692-4927 & Kathleen Quinones 8:00 am Morning Mass Religious Education: Christine Humphries Intention: Rose & Florien Hartler † [email protected] Wednesday, August 25 Sacristan: Maggie Hill 904-797-2733 5:00 pm Confessions (until 5:30 pm) 6:00 pm Evening Mass NEW PARISHIONERS Intention: Cathy Dupont (SI) Welcome! Please take a few minutes to complete a confidential registration form which can be found in the Church lobby. -

French Catholicism's First World War

University of Pennsylvania ScholarlyCommons Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations 2016 Calvary Or Catastrophe? French Catholicism's First World War Arabella Leonie Hobbs University of Pennsylvania, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations Part of the European History Commons, Other Languages, Societies, and Cultures Commons, and the Religion Commons Recommended Citation Hobbs, Arabella Leonie, "Calvary Or Catastrophe? French Catholicism's First World War" (2016). Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations. 2341. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/2341 This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/2341 For more information, please contact [email protected]. Calvary Or Catastrophe? French Catholicism's First World War Abstract CALVARY OR CATASTROPHE? FRENCH CATHOLICISM’S FIRST WORLD WAR Arabella L. Hobbs Professor Gerald Prince The battlefield crucifixes that lined the Western Front powerfully connected industrialized warfare with the Christian past. This elision of the bloody corporeality of the crucifixion with the bodily suffering wrought by industrial warfare forged a connection between religious belief and modern reality that lies at the heart of my dissertation. Through the poignancy of Christ’s suffering, French Catholics found an explanatory tool for the devastation of the Great War, affirming that the blood of ther F ench dead would soon blossom in rich harvest. This dissertation argues that the story of French Catholicism and the Great War uncovers a complex and often dissonant understanding of the conflict that has become obscured in the uniform narrative of disillusionment and vain sacrifice ot emerge in the last century. Considering the thought to emerge from the French renouveau catholique from 1910 up to 1920, I argue that far from symbolizing the modernist era of nihilism, the war in fact created meaning in a world that had lost touch with its God. -

De Pietas Van Jacobus Boonen, Aartsbisschop Van Mechelen (1621-1655)

DE PIETAS VAN JACOBUS BOONEN, AARTSBISSCHOP VAN MECHELEN (1621-1655) Alain Debbaut 19790283 Promotor: Prof. dr. René Vermeir Masterproef voorgelegd voor het behalen van de graad van master in de geschiedenis Academiejaar 2017 – 2018 Universiteit Gent Examencommissie Geschiedenis Academiejaar 2017-2018 Verklaring in verband met de toegankelijkheid van de scriptie Ondergetekende, Alain Debbaut Afgestudeerd als master in de geschiedenis aan de Universiteit Gent in het academiejaar 2017-2018 en auteur van een scriptie met als titel: De pietas van Jacobus Boonen, aartsbisschop van Mechelen (1621-1655) verklaart hierbij dat hij geopteerd heeft voor de hierna aangestipte mogelijkheid in verband met de consultatie van zijn scriptie: • De scriptie mag steeds ter beschikking gesteld worden van elke aanvrager o De scriptie mag enkel ter beschikking gesteld worden met uitdrukkelijke schriftelijke goedkeuring van de auteur (maximumduur van deze beperking: 10 jaar) o De scriptie mag ter beschikking gesteld worden van een aanvrager na een wachttijd van … jaar (maximum 10 jaar) o De scriptie mag nooit ter beschikking gesteld worden van een aanvrager (maximumduur van het verbod: 10 jaar) Elke gebruiker is te allen tijde verplicht om, wanneer van deze scriptie gebruik wordt gemaakt in het kader van wetenschappelijke en andere publicaties, een correcte en volledige bronverwijzing in de tekst op te nemen Gent, 22 mei 2018 Alain Debbaut I DANKWOORD Bij het schrijven van deze masterscriptie kwamen meerdere zaken op een prettige manier samen. Om te beginnen was ik al op mijn zestiende geïnteresseerd geraakt in vroegmoderne kerkgeschiedenis, toen ik van mijn leraar Latijn voor straf enkele visitationes uit het pas gepubliceerde Itinerarium van Gents bisschop Antonius Triest (1623-1654) ‘mocht’ vertalen. -

Bodies of Knowledge: the Presentation of Personified Figures in Engraved Allegorical Series Produced in the Netherlands, 1548-1600

University of Pennsylvania ScholarlyCommons Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations 2015 Bodies of Knowledge: The Presentation of Personified Figures in Engraved Allegorical Series Produced in the Netherlands, 1548-1600 Geoffrey Shamos University of Pennsylvania, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations Part of the History of Art, Architecture, and Archaeology Commons Recommended Citation Shamos, Geoffrey, "Bodies of Knowledge: The Presentation of Personified Figures in Engraved Allegorical Series Produced in the Netherlands, 1548-1600" (2015). Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations. 1128. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/1128 This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/1128 For more information, please contact [email protected]. Bodies of Knowledge: The Presentation of Personified Figures in Engraved Allegorical Series Produced in the Netherlands, 1548-1600 Abstract During the second half of the sixteenth century, engraved series of allegorical subjects featuring personified figures flourished for several decades in the Low Countries before falling into disfavor. Designed by the Netherlandsâ?? leading artists and cut by professional engravers, such series were collected primarily by the urban intelligentsia, who appreciated the use of personification for the representation of immaterial concepts and for the transmission of knowledge, both in prints and in public spectacles. The pairing of embodied forms and serial format was particularly well suited to the portrayal of abstract themes with multiple components, such as the Four Elements, Four Seasons, Seven Planets, Five Senses, or Seven Virtues and Seven Vices. While many of the themes had existed prior to their adoption in Netherlandish graphics, their pictorial rendering had rarely been so pervasive or systematic.