Sulphur Springs Depot: a Brief Introduction

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

ANNUAL REPORT 2014-2015 School of Sciences and Mathematics Annual Report 2014‐2015

ANNUAL REPORT 2014-2015 School of Sciences and Mathematics Annual Report 2014‐2015 Executive Summary The 2014 – 2015 academic year was a very successful one for the School of Sciences and Mathematics (SSM). Our faculty continued their stellar record of publication and securing extramural funding, and we were able to significantly advance several capital projects. In addition, the number of majors in SSM remained very high and we continued to provide research experiences for a significant number of our students. We welcomed four new faculty members to our ranks. These individuals and their colleagues published 187 papers in peer‐reviewed scientific journals, many with undergraduate co‐authors. Faculty also secured $6.4M in new extramural grant awards to go with the $24.8M of continuing awards. During the 2013‐14 AY, ground was broken for two 3,000 sq. ft. field stations at Dixie Plantation, with construction slated for completion in Fall 2014. These stations were ultimately competed in June 2015, and will begin to serve students for the Fall 2015 semester. The 2014‐2015 academic year, marked the first year of residence of Computer Science faculty, as well as some Biology and Physics faculty, in Harbor Walk. In addition, nine Biology faculty had offices and/or research space at SCRA, and some biology instruction occurred at MUSC. In general, the displacement of a large number of students to Harbor Walk went very smoothly. Temporary astronomy viewing space was secured on the roof of one of the College’s garages. The SSM dean’s office expended tremendous effort this year to secure a contract for completion of the Rita Hollings Science Center renovation, with no success to date. -

History of the Orange Belt Railway

HISTORY OF THE ORANGE BELT RAILWAY As the 1880's unfolded, Florida's frontier was being penetrated by a system of three-foot gauge railroads, spurred on by a generous state land grant. This story focuses on one of the last common carrier narrow gauge roads to be built in Florida, which was also one of the last to be converted to standard gauge. Petrovitch A. Demenscheff was born in Petrograd, Russia in 1850. His family was of the nobility with large estates. He was the first cousin of Prince Petroff and a captain in the Imperial Guard. He received training as a forester managing his large family estates, which would serve him well in the future. In 1880 he was exiled from Russia, and with his wife, children and servant immigrated to America, Anglicizing his name to Peter Demens. For some odd reason he headed south to Florida and obtained a job as a laborer at a sawmill in Longwood, Florida. He worked hard and within a year was appointed manager. Later with the money he saved he became partners with the owners and then quickly bought them out. Demens soon became one of the biggest contractors in the state, building houses, stations, hotels and railroads throughout Florida. One railroad contract was the narrow gauge Orange Belt Railway that he took over when they couldn't pay for the work. The Orange Belt Railway at first was a real estate promotion, using mule power (his name was Jack) and wood rails from Longwood to Myrtle Lake. When Demens took the road over he formed an operating company called the Orange Belt Investment Company. -

Florida Historical Quarterly

COVER Two eastbound trains and passengers appear to be waiting at the Archer depot for a westbound train from Gainesville, ca. 1910. The wood-burning freight on the right has arrived from Cedar Key, while the coal-burning train on the left has come from the south. The line on the right is the original “Florida Railroad” built by Senator David Levy Yulee’s company. Originating in Fernandina, the line had reached Archer by 1859, and was completed to its terminus at Cedar Key in 1861. The line on the left was built to haul phosphate from the mines in the area and other freight. It eventually went all the way to Tampa. From the collection of Herbert J. Doherty, Jr. Gainesville. Historical uarterly Volume LXVIII, Number July 1989 THE FLORIDA HISTORICAL SOCIETY COPYRIGHT 1989 by the Florida Historical Society, Tampa Florida. Second class postage paid at Tampa and DeLeon Springs, Florida. Printed by E. O. Painter Printing Co., DeLeon Springs, Florida. (ISSN 0015-4113) THE FLORIDA HISTORICAL QUARTERLY Samuel Proctor, Editor Everett W. Caudle, Editorial Assistant EDITORIAL ADVISORY BOARD David R. Colburn University of Florida Herbert J. Doherty, Jr. University of Florida Michael V. Gannon University of Florida John K. Mahon University of Florida (Emeritus) Jerrell H. Shofner University of Central Florida Charlton W. Tebeau University of Miami (Emeritus) Correspondence concerning contributions, books for review, and all editorial matters should be addressed to the Editor, Florida Historical Quarterly, Box 14045, University Station, Gainesville, Florida 32604-2045. The Quarterly is interested in articles and documents pertaining to the history of Florida. -

A Pedigree of Pinellas Place-Names

University of South Florida Digital Commons @ University of South Florida USF St. Petersburg campus Faculty Publications USF Faculty Publications 2011 A Pedigree of Pinellas Place-names James Anthony Schnur Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.usf.edu/fac_publications Recommended Citation Schnur, James Anthony, "A Pedigree of Pinellas Place-names" (2011). USF St. Petersburg campus Faculty Publications. 2975. https://digitalcommons.usf.edu/fac_publications/2975 This Other is brought to you for free and open access by the USF Faculty Publications at Digital Commons @ University of South Florida. It has been accepted for inclusion in USF St. Petersburg campus Faculty Publications by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ University of South Florida. For more information, please contact [email protected]. A Pedigree of Pinellas Place-names James Anthony Schnur Florida is known for its odd and colorful place-names. People pay millions of dollars to live in a “rat’s mouth” (“ Boca Raton ” in Spanish), while others call Two Egg or Sopchoppy their home. Here are some names from early settlements along the Pinellas Peninsula: Anclote: The word derives from the Spanish word for a kedge or a small anchor commonly used by sailing vessels. Maps from the 1700s forward note the Anclote River. After the Civil War, Frederic Meyer left Marion County and settled on lands north of the river. By the 1870s, a small community formed along the north shore of the river, west of present-day Tarpon Springs. By one pioneer’s account, over ninety-percent of the men who came to the settlement in vessels were “of English extraction,” many of them from the British West Indies. -

Hamilton Disston

HAMILTON DISSTON Hamilton Disston was born August 23, 1844, in Philadelphia. He worked in his father's saw manufacturing plant until he signed up to join the troops fighting in the Civil War. Twice during the early years of fighting, he enlisted, only to be hauled home after his father paid the bounty for another soldier to take his son's place. He eventually accepted his son's wishes and supplied Hamilton and 100 other workers from the saw plant with equipment to form the Disston Volunteers. Hamilton served as a private in the Union Army until the end of the war. Hamilton Disston purchased four million acres of marshland shortly after the Civil War. Included in his purchase was the small trading post of Allendale, which was eventually renamed Kissimmee. Disston wished to drain the area surrounding Kissimmee and deepen the Kissimmee River, so products could be shipped into the Gulf of Mexico and beyond. Many steamboats passed through the area with cargoes of cypress lumber and sugar cane. Disston committed suicide on April 30, 1896, after a disastrous freeze led many families to relocate further south. Disston's land company stopped payment on bonds and returned to Philadelphia. Hamilton Disston Biography by Mary Ellen Wilson and is located in the American National Biography, published by Oxford University Press, 1999. Photo from Ken Milano's archives. Hamilton Disston (23 Aug. 1844-30 Apr. 1896), land developer, was born in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, the son of Henry Disston, an industrialist, and Mary Steelman. At the age of fifteen Disston started as an apprentice in one of the divisions of his father's factory, Keystone Saw, Tool, Steel and File Works, setting a precedent for other family members. -

February 1, 2020

Russian Heritage February 1, 2020 Russian Heritage Newsletter SAINT PETERSBURG, TAMPA, CLEARWATER, FLORIDA R u s s i a n H e r i t a g e Russian Heritage Russian Heritage NEW L o g o Winter Ball Webpage Is Being Updated We have a new logo for our It took a lot of effort, nerves, The time has come to finally get organization. Thank you stress and patience, to put this a new look and add many more Michael our webmaster who Ball together. We want to features to our webpage. It’s a helped design it. Thank All those Board tedious process but we want to Members who managed to Thank Michael the web designer make this a great event! But and maintainer for making it also thank all RH Members happen along with Zina Downen and guests who attended too. one of our Board members. RUSSIAN HERITAGE WINTER BALL A Fun Time Enjoyed by All! We had our 24th Annual Winter Ball on Saturday, January 11th, 2020 @ the St. Petersburg Yacht Club. Over 250 people attended, with several local politicians and state congressmen. It was possibly the “Best Ball Yet!” quoted by many. Rrussianheritage.org 1 Russian Heritage February 1, 2020 St Petersburg Sister Cities (Florida & Russia) This year Russian Heritage plans to get this project off the shelves and into action. After many years of silence, work has been progressing a step at a time, contacting officials from both sides. One of our main goals is to organize the student exchange program, we plan to have several activities with art and perhaps theatre events. -

The Florida Historical Quarterly Volume Xlv October 1966 Number 2

O CTOBER 1966 Published by THE FLORIDA HISTORICAL SOCIETY THE FLORIDA HISTORICAL SOCIETY THE HISTORICAL SOCIETY OF FLORIDA, 1856 THE FLORIDA HISTORICAL SOCIETY, successor, 1902 THE FLORIDA HISTORICAL SOCIETY, incoporated, 1905 by GEORGE R. FAIRBANKS, FRANCIS P. FLEMING, GEORGE W. WILSON, CHARLES M. COOPER, JAMES P. TALIAFERRO, V. W. SHIELDS, WILLIAM A. BLOUNT, GEORGE P. RANEY. OFFICERS WILLIAM M. GOZA, president HERBERT J. DOHERTY, JR., 1st vice president JAMES C. CRAIG, 2nd vice president MRS. RALPH F. DAVID, recording secretary MARGARET L. CHAPMAN, executive secretary DIRECTORS CHARLES O. ANDREWS, JR. MILTON D. JONES EARLE BOWDEN FRANK J. LAUMER JAMES D. BRUTON, JR. WILLIAM WARREN ROGERS MRS. HENRY J. BURKHARDT CHARLTON W. TEBEAU FRANK H. ELMORE LEONARD A. USINA WALTER S. HARDIN JULIAN I. WEINKLE JOHN E. JOHNS JAMES R. KNOTT, ex-officio SAMUEL PROCTOR, ex-officio (and the officers) (All correspondence relating to Society business, memberships, and Quarterly subscriptions should be addressed to Miss Margaret Ch apman, University of South Florida Library, Tampa, Florida 33620. Articles for publication, books for review, and editorial correspondence should be ad- dressed to the Quarterly, Box 14045, University Station, Gainesville, Florida, 32601.) * * * To explore the field of Florida history, to seek and gather up the ancient chronicles in which its annals are contained, to retain the legendary lore which may yet throw light upon the past, to trace its monuments and remains, to elucidate what has been written to disprove the false and support the true, to do justice to the men who have figured in the olden time, to keep and preserve all that is known in trust for those who are to come after us, to increase and extend the knowledge of our history, and to teach our children that first essential knowledge, the history of our State, are objects well worthy of our best efforts. -

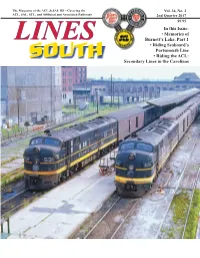

In This Issue: • Memories of Burnett's Lake, Part 1 • Riding Seaboard's

The Magazine of the ACL & SAL HS – Covering the Vol. 34, No. 2 ACL, SAL, SCL, and Affiliated and Associated Railroads 2nd Quarter 2017 $9.95 In this Issue: • Memories of LINES Burnett’s Lake, Part 1 • Riding Seaboard’s Portsmouth Line SOUTH • Riding the ACL: Secondary Lines in the Carolinas Membership Classes Regular: $35 for one year or $65 for two years. Memberships are concur- rent with the calendar year; to join or renew during the year, contact us at our LINES address below or at [email protected]. Sustaining: $60 for one year or $115 for two years. These amounts in- clude $25 and $50, respectively, in tax-deductible contributions. Century Club: $135 for one year, which includes a complimentary calen- SOUTH dar and a tax-deductible contribution of $87. We gladly accept other contributions, either financial or historical Volume 34, No. 2, 2nd Quarter 2017 materials for our archives, all of which are tax-deductible to the extent The Magazine of the ACL & SAL HS – Covering the provided by law. ACL, SAL, SCL, and Affiliated and Associated Railroads Your membership dues include quarterly issues of LINES SOUTH, participa- tion in Society-sponsored events and projects, voting rights on issues brought before the membership, and research assistance on members’ questions. LINES SOUTH STAFF Foreign (includes Canada): Membership with delivery via surface mail is Editor $60 per year or $120 for two years. For sustaining foreign memberships, add Larry Goolsby $25 for one year and $50 for two years. We can accept foreign memberships only by Visa, MasterCard, Discover, or PayPal. -

2002 Model Railroading ▼ 5 Serving Ohio Bound and the Nation Acy Road of Service Acy V Es 845

▼ PASSENGER OPERATIONS ▼ CONTAINERS KSCU TO MATS ▼ DIESEL DETAIL: SP PA/PBs ▼ January 2002 $4.50 Higher in Canada VerticalVertical AccessAccess HatchesHatches Page 42 VirginiaVirginia SouthernSouthern Page 36 “Painted“Painted On”On” SignsSigns SOU RC Car Page 40 01 > EMDEMD GP40sGP40s Page 28 Seaboard Page 21 Page 28 0 7447 0 91672 7 I Asthe nation's box car fleet began to age in the early 1970's, it NEW SIECO BOX CARS became time for the birth of a brand new generation of freight cars. The Sieco exterior post plate C 50 foot boxcar was developed to fit SO' SIECO BOX CARS ITEM # DESCRIPTION the needs of both Class One and independent per diem short lines G4200 UNDECORATED and has performed yeoman service for more than three decades. G4201 B&M #1 Our Genesis 50' Sieco Boxcar provides the modern age model G4202 B&M #2 railroader with a wealth of prototypical fidelity. Stand alone details, G4203 MILWAUKEE #1 machined metal wheel sets with true-to-scale bearing cups that G4204 MILWAUKEE #2 actually rotate and photo-documented razor sharp graphics are a G4205 N&W#1 G4206 N&W#2 just a few of the benefits of this exceptional boxcar. This makes it a G4207 P&LE #1 "must have" for the realism inspired model rai lroad enthusiast or G4208 P&LE #2 the model railroader who demands that thei r rolling stock be as G4209 ST. LAWRENCE # 1 close to real as it gets. G4210 ST. LAWRENCE #2 January 2002 40 VOLUME 32 NUMBER 1 Photo by James A. -

The Pier—Can’T Live with It, Can’T Live Without It Edmund Gallizzi

The Pier—Can’t live with it, Can’t live without it Edmund Gallizzi Although there has been a bit of controversy over the proposed new St. Petersburg pier with some suggesting that the pier should not be replaced, piers have been an important part of the City’s character, traditions and history. It could be said that the very existence of St. Petersburg was based on a pier. (Maybe wharf is a better term.) The wharf was the western terminus of the Orange Belt railway and was completed in 1889 before there was a St. Petersburg. Peter Demens, an immigrant from St. Petersburg, Russia, was the railway’s owner and the city was named for his home town. He had expected to bring his railroad to Disston City, now Gulfport, which was owned by Hamilton Disston, but when they could not come to an agreement, he reached an accord with John and Sarah Williams who owned much of the land that is now downtown St. Petersburg. Some had expected the town to be named Williamsville. The railroad brought growth to the previously isolated area. The railroad extended out 2000 feet on the Orange Belt wharf to where a water depth of 12 feet allowed steamships and schooners to dock and transfer cargo to and from freight trains. The wharf, which was located at what is now Demens Landing Park, allowed fishing and included a bathing pavilion that was styled after the newly built Detroit Hotel, which was owned by Demens. In 1895, Henry Plant, Tampa mogul, acquired the railroad and began charging a wharf docking fee to limit competition with his steamship line. -

CITY of WAYCROSS BUDGET FY2018 July 1, 2017 –June 30,2018

CITY OF WAYCROSS BUDGET FY2018 July 1, 2017 –June 30,2018 ADOPTED JUNE 20, 2017 City of Waycross Budget FY2018 2018 Table of Contents INTRODUCTION .......................................................................................................................... 2 Budget Objective ........................................................................................................................ 2 Distinguished Budget Award ...................................................................................................... 4 Resolution (Copy) ....................................................................................................................... 5 Mission Statement ....................................................................................................................... 7 Our Guiding Principles ............................................................................................................... 8 Budget Message from the City Manager .................................................................................... 9 Budget Summary ...................................................................................................................... 15 Governmental Funds ............................................................................................................. 16 Internal Service Funds .......................................................................................................... 19 Enterprise Funds .................................................................................................................. -

Tampa Bay's Railroad History

Tampa Bay’s RailRoad HisToRy all aboard: Tampa Bay’s railroad history Silvery-sleek, on sun-bleached tracks With barrel-chested engines, Dolomite black “Those were the trains of yesterday! “ But where might smoke and thunder stay? 71st New York Where might great metro-liners rest, Volunteers arrive in Port Tampa, As they rumble ’cross-the-country with their smoke-filled crests? 1898, courtesy USF Library from The Epic of Tampa Union Station Special Collections by James E. Tokley Sr., Hillsborough County Poet Laureate Sanford-St. Petersburg train, 1893, courtesy Tampa-Hillsborough County Public Library System Henry Plant supervising the transport of Army troops by railroad to Tampa, where they boarded ships to fight the Spanish-American War in Cuba, 1898; Tampa Bay Times photo Newspaper in Education NIE staff LAFS.4-5.L.1.2; LAFS.4-5.L.1.3; LAFS.4-5.L.1.4; LAFS.4-5.L.1.5; LAFS.4- The Tampa Bay Times Newspaper in Jodi Pushkin, manager, [email protected] 5.L.1.6 Education (NIE) program is a cooperative Sue Bedry, development specialist, [email protected] effort between schools and the Times Hillsborough County Historic Preservation Challenge Grant to encourage the use of newspapers in © Tampa Bay Times 2014 This project was supported by a Historic Preservation Challenge Grant print and electronic form as educational awarded by the Hillsborough County Board of County Commissioners. The resources. Credits Hillsborough County Historic Preservation program aims to foster planning Our educational resources fall Researched and written by Jodi Pushkin and Sue Bedry, Tampa Bay Times that “encourages the continued use and preservation of historic sites and into the category of informational Designed by Stacy Rector, Fluid Graphic Design LLC structures.” The Historic Preservation Challenge Grant program was founded in text.