The Teacher Rebellion Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2018 with Funding from Kahle/Austin Foundation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

National Register of Historic Places Inventory—Nomination Form 1

NPS Form 10-900 OMB No. 1024-OO18 Exp. 10-31-84 United States Department off the Interior National Park Service National Register of Historic Places Inventory—Nomination Form See instructions in How to Complete National Register Forms Type aM entries—complete applicable sections_______________ 1. Name historic n.a. and/or common Main Street Historic District 2. Location 5 street & number___please see map and inventory forms not for publication city, town Fort Atkinson vicinity of state WI code 55 county Jefferson code 055 3. Classification Category Ownership Status Present Use X district public X occupied agriculture museum building(s) private unoccupied _ X_ commercial _X_park structure X both work in progress _ y- educational X private residence __ site Public Acquisition Accessible entertainment religious object in process X yes: restricted X government scientific being considered yes: unrestricted _X_ industrial transportation X not applicable no military other: 4. Owner of Property name please see inventory forms street & number • n.a. city, town n.a. vicinity of state n.a, courthouse, registry of deeds, etc. Jefferson County Courthouse street & number 320 S. Main Street city, town Jefferson state WI 53540, 6. Representation in Existing Surveys Wisconsin Inventory of title Historic Places nas tnis property been determined eligible? __ yes x no date 1975 federal X state __ county __ local depository for survey records State Historical Society of Wisconsin city, town Madison state WI 53706 7. Description Condition Check one Check one excellent deteriorated unaltered X original site _X_good ruins _JL_ altered moved date fair unexposed Describe the present and original (if known) physical appearance Note: The current district has 60 buildings. -

Restaurant Trends App

RESTAURANT TRENDS APP For any restaurant, Understanding the competitive landscape of your trade are is key when making location-based real estate and marketing decision. eSite has partnered with Restaurant Trends to develop a quick and easy to use tool, that allows restaurants to analyze how other restaurants in a study trade area of performing. The tool provides users with sales data and other performance indicators. The tool uses Restaurant Trends data which is the only continuous store-level research effort, tracking all major QSR (Quick Service) and FSR (Full Service) restaurant chains. Restaurant Trends has intelligence on over 190,000 stores in over 500 brands in every market in the United States. APP SPECIFICS: • Input: Select a point on the map or input an address, define the trade area in minute or miles (cannot exceed 3 miles or 6 minutes), and the restaurant • Output: List of chains within that category and trade area. List includes chain name, address, annual sales, market index, and national index. Additionally, a map is provided which displays the trade area and location of the chains within the category and trade area PRICE: • Option 1 – Transaction: $300/Report • Option 2 – Subscription: $15,000/License per year with unlimited reporting SAMPLE OUTPUT: CATEGORIES & BRANDS AVAILABLE: Asian Flame Broiler Chicken Wing Zone Asian honeygrow Chicken Wings To Go Asian Pei Wei Chicken Wingstop Asian Teriyaki Madness Chicken Zaxby's Asian Waba Grill Donuts/Bakery Dunkin' Donuts Chicken Big Chic Donuts/Bakery Tim Horton's Chicken -

Clifton Chronicle

SUMMER 2012 Volume Twenty-Two Number One CA Publicationlifton of Clifton Town Meeting C You Dohronicle It You Write It We Print It Cincinnati, Ohio 45220 Box 20067 P.O. Clifton Chronicle Clifton Home Composite—You will not be touring this home any time soon, made up of the homes on Evanswood Place by Bruce Ryan, former resident and producer of yearly Evanswood block party invitation where this illustration first appeared. Clifton House Tour this Mother’s Day By Eric Clark Every third year on Mother’s are like stepping back in time to the sored them throughout the ‘70s and Day, a group of Clifton homeowners period in which they were built. ‘80s, taking a hiatus between 1988 open their doors to greater Cincinnati Although we do not disclose and 1997. Since the resumption and say, “Come on in and have a look pictures or the addresses of the of the tours, the event has drawn around!” So, mark your calendars for homes until the day of the tour. We people from all over Cincinnati and Mother’s Day, May 13, 2012. are confident that if you have an ap- has been a great way to spend part Clifton Town Meeting has lined preciation for architecture or interior of Mother’s Day. up some great houses for the 2012 design, or if you just enjoy touring Tickets are $17.50 in advance tour and it includes something for beautiful Clifton homes, you will and $22.50 the day of the tour. Tick- everyone with a wide and eclectic NOT be disappointed. -

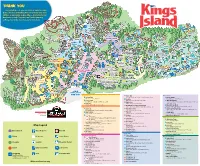

2008 Map Kings Island

THANK YOU . for including us in your vacation or entertainment plans. We’ll do everything we can to make your visit with us as enjoyable as possible — just let us know how we can help. Together, we’ll make your day at Kings Island the most fun you’ve ever had. THE BEAST FIREhawK THE VortEX LAUNCH THE CRYPT PAD SHAKE, rattlE tasmanian & ROLL TYPHOON FLIGHT OF FEAR RIVERTOWN ZEPHYR SNOWY RIVER BACKLOT STUNT KANGAROO COASTER rampagE WHITE WatER LAGOON CONEY K.I. & MIAMI CANYON VALLEY RAILROAD KOALA MALL SPLASH PIPELINE paraDISE DODGEM BOOMERANG MONSTER wallabY BAY WHARF SCRAMBLER WILD GRAND THORNBERRy’S SYDNEY THE RACER SIDEWINDER JACKEROO CAROUSEL RIVER ADVENTURE BONDI LANDING ADVENTURE PIPELINE Down UNDER EXPRESS RUgrats RUnawaY THUNDER EIFFEL Phantom REptar SLING SHOT TOWER FLYERS grEat barriER CROCODILE REEF RUN OKTOBERFEST awESOME KOOKABURRA TIMMy’S AUSSIE TWISTER baY AirtoURS PICNIC PLANKTON’S GROVE PLUNGE VIKING LITTLE BILL’S SPONGEBOB FURY GIGGLE COASTER SQUAREpants BIKINI THUNDER DELIRIUM coolangatta ALLEY BOTTOM BASH RACER SON OF SCOOBY-DOO NICK-O-ROUND BEAST INTERNATIONAL & The Haunted Castle STREET LAZYTOWN sportacoptERS DROP XTREME BLUES’ SWIPERS TOWER SKYFLYER SKIDOO SWEEPERS NICKELODEON AVatar: THE BACKYARDIGANS’ UNIVERSE LAST AIRBENDER SWING-ALONG LA ADVENTURA ACTION JIMMY NEUTRON’S NICK JR. DE AZUL ZONE ATOM SMASHER DRIVERS GO DIEGO GO FAIRLY ODD CONGO COASTER FALLS MAIN INVErtigo ENTRANCE AND EXIT Action Zone Skyline Chili Rivertown FLIGHT DECK Ice Cream Zone Cincinnati’s famous chili on a cheese coney dog, 3-way or 4-way -

TOP 100 2016 Chain Index

TOP 100 2016 Chain Index LATEST YEAR RANKINGS SYSTEM- % GROWTH, % GROWTH, % GROWTH, SALES WIDE SYSTEM NO. OF NO. OF NO. OF PER COMPANY HEADQUARTERS PARENT COMPANY SEGMENT SALES SALES UNITS UNITS FRAN. UNITS UNIT 7-Eleven Dallas Seven & i Holdings Co. Ltd. C-Store 30 58 5 65 28 97 Applebee's Neighborhood Glendale, Calif. DineEquity Inc. Casual Dining 11 67 26 64 43 29 Grill & Bar Arby's Atlanta Roark Capital Group LSR/Sandwich 21 34 17 79 76 70 Auntie Anne's Lancaster, Pa. Roark Capital Group Beverage-Snack 87 38 35 27 32 95 Baskin-Robbins Glendale, Calif. Dunkin' Brands Group Inc. Beverage-Snack 81 44 18 60 53 99 BJ’s Restaurant Huntington Beach, Calif. BJ's Restaurants Inc. Casual Dining 51 33 95 13 — 5 & Brewhouse Bob Evans Restaurants New Albany, Ohio Bob Evans Farms Inc. Family Dining 50 93 64 99 — 44 Bojangles' Famous Charlotte, N.C. Advent International Corp. Chicken 47 20 55 18 40 42 Chicken 'n Biscuits Bonefish Grill Tampa, Fla. Bloomin' Brands Inc. Casual Dining 78 81 89 33 58 20 Boston Market Golden, Colo. Sun Capital Partners Inc. Chicken 79 73 74 63 2 57 Buffalo Wild Wings Minneapolis Buffalo Wild Wings Inc. Casual Dining 18 25 38 14 77 18 Grill & Bar Burger King Miami Restaurant Brands International Inc. LSR/Burger 4 54 7 71 57 62 California Pizza Kitchen Los Angeles Golden Gate Capital Casual Dining 73 78 91 72 58 19 Captain D's Seafood Kitchen Nashville, Tenn. Centre Partners Management LLC LSR/Seafood 84 50 66 77 58 72 Carl's Jr. -

SC-Cardinal-Magazine-2018.Pdf

the CARDINALSt. Charles Preparatory School Alumni Magazine Fall 2018 Inside Read about The Vision for the Future, the school’s $20 million – and most ambitious initiative ever – meant to secure a bright future for generations of students into the next century (page 3). In its fourth year, our “Evening With...” speaker series welcomed Wes Moore to campus on September 6th. View photo galleries of the day’s activities and read about the inspirational messages he shared with students and the school community (pages 4-9). Read about the 2017 Borromean Lecture and the message delivered by guest presenter Ken Woodward last November (pages 13-18) as well as internationally acclaimed artist Jan Dilenschneider’s “ECO Vision” show held this summer to benefit the school (pages 19-20). The Cardinal Community always takes time to gather together to celebrate and commemorate their ties to St. Charles. View hundreds of photos and read about these events: the 30th Annual Cardinal Christmas (pages 50-59), Spaghetti Dinner (pages 60-67), Father/Son Mass & Breakfast (pages 68-73), Alumni Golf Outing (pages 28-29) and Cardinal Society gathering (pages 114-119). In November, the school honored several of its most loyal, generous and accomplished community members at two special recognition celebrations: the 2017 Borromean Awards at the Feast Day Mass (pages 25-26) and the Distinguished Alumnus Awards at the Thanksgiving liturgy (page 27). We know that the St. Charles Community is always excited and proud to hear about the accomplishments of our student- athletes and their service to their fellow man. National Merit honorees, an appointee to the U.S. -

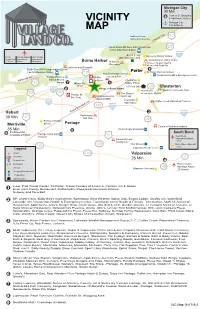

VLC Map 11X17v5-2

Michigan City 30 Min 8 Franklin St. Shopping & Lighthouse Outlets 20 VICINITY Michigan City MAP Port AuthorityCalumet Trail Indiana Dunes 12 National Lakeshore Calumet Trail 94 South Shore RR Dune Park (Chesterton) 20 1:35 to Millennium Station Seven Peaks Discovery Charter School 94 O’Hare Chicago Midway Gary Chicago Waterpark Duneland 421 International International International Indiana Dunes Visitor Center 1:10 Hour 1 Hour 25 Minutes Burns Harbor Marquette Fairhaven Baptist Church, Greenway College, and Academy Lakefront and Riverwalk South Shore RR Portage/Ogden Dunes 2 1:26 to Millennium Station Porter St Patrick Catholic School 12 Yost Elementary School Chesterton Health & Emergency Center Portage Public & BH Fire Lakeland Park Marquette Trail Marina Shores BH Police Chesterton 12 Marina 7 Bass Pro 1 Middle School Shops US Post Office 49 Chesterton 6 Village in Burns Harbor 94 Westchester Sand Creek Country Club 20 The Brassie Intermediate School 20 Portage #2 Imagination Glen Golf Club Fire Dept. Outdoor BMX Chesterton Coffee Creek Watershed Preserve 90 High School 149 65 90 Hobart Prairie-Duneland Trail 3 Robbinhurst 90 30 Min 6 Golf Club 49 Portage Christian School Portage Merriville Courts of Northwest Indiana 35 Min 5 Porter Regional Hospital Southlake Mall South Bend 9 Crossings at Hobart Portage Community Hospital 6 South Bend 6 Sunset Hill Farm International Airport 1 Hour County Park 149 49’er Drive-in Notre Dame University 130 1 Hour 2 Legand Valparaiso Health Center 421 Airport 130 Valparaiso Fire/Police 25 Min 2 Medical -

Winona Daily News Winona City Newspapers

Winona State University OpenRiver Winona Daily News Winona City Newspapers 11-27-1962 Winona Daily News Winona Daily News Follow this and additional works at: https://openriver.winona.edu/winonadailynews Recommended Citation Winona Daily News, "Winona Daily News" (1962). Winona Daily News. 333. https://openriver.winona.edu/winonadailynews/333 This Newspaper is brought to you for free and open access by the Winona City Newspapers at OpenRiver. It has been accepted for inclusion in Winona Daily News by an authorized administrator of OpenRiver. For more information, please contact [email protected]. 707 Carrying 97 Crashes in Peru Plane Flying Kennedy Is CafTvassers Sencf Governor Heartened by From Rio to Inspection Trip Decision to Supreme Court Los Angeles ST. PAUL (AP) — The Minne- J. Neil Morton, attorney for Gov. cratic Lt. Gov, Karl Rolvaag. the 87 counties. By DIEGO GONZALES By FRED S. HOFFMAN sota Supreme Court today set a Elmer L. Andersen. The order The chief issue, as it has been Today's action followed a three- LIMA, Peru (AP)-A Brazilian WASHINGTON (AP)-President hearing for 2 p.m. Wednesday on for hearing was signed by Chief for three weeks, is acceptance or way split by the canvassing board jet airliner, flying toward Los An- Kennedy and the nation's mili- a legal action; aimed at forcing Justice Oscar R. Knutson. rejection of amended vote totals Monday which set the stage ior geles with 97 persons aboard, was tary chiefs returned "heartened the state canvassing board to cer- Morton asks the canvassing irom 10 counties. The altered re- the close governor race to go into found wrecked 75 miles south tify a winner in the governor elec- board to show cause of and encouraged" after seeing the ¦ ¦ why Ander- turns put Andersen in the lead. -

Facultad De Medicina

FACULTAD DE MEDICINA LICENCIATURA EN NUTRICIÓN ANTOLOGIA DE SOCIOCULTURA ALIMENTARIA INÉS AIMME ITURBIDE PARDIÑAS ÍNDICE Índice……………………………………………………………………………………….3 Prólogo…………………………………………………………………………………….4 Introducción…………………………………………………………………….……….10 Tema 1 Debates actuales en la sociocultura de la alimentación………………14 Práctica 1………………………………………………………………………………...18 Tema 2 La importancia de la sociocultura de la alimentación en México……19 Práctica 2………………………………………………………………………………...22 Tema 3 La alimentación en México: Un estudio a partir de la encuesta……..26 Nacional de ingresos y gastos de los hogares Práctica 3………………………………………………………………………………...30 Tema 4 Alimentación y Religión……………………………………………………..31 Práctica 4………………………………………………………………………………...39 Tema 5 Aspectos sociales……………………………………………………………39 Práctica 5………………………………………………………………………………...43 Tema 6 Un vistazo a la cultura culinaria en México……………………………...43 Práctica 6………………………………………………………………………………...60 Tema 7 Armonización del vino con los alimentos………………………………..60 Práctica 7………………………………………………………………………………...77 Tema 8 Sociología de la alimentación alrededor del mundo…………………..78 2 Práctica 8………………………………………………………………………………...88 Tema 9 Un vistazo a la cocina Norteamericana…………………………………..90 Práctica 9……………………………………………………………………………….137 Tema 10 Un vistazo a la cocina China…………………………………………….138 Práctica 10……………………………………………………………………………..158 Tema 11 Un vistazo a la cocina Japonesa………………………………………..159 Práctica 11………………………………………………………………………….…..181 Tema 12 Un vistazo a la cocina Tailandesa……………………………………...182 -

Companies Hiring 14 – 17 Year Olds Skyhawks VSA Resorts Burger

Companies Hiring 14 – 17 year olds Skyhawks Skyhawks is a youth sports camp organization based in Spokane, WA. It is currently looking for high school and college students who are interested in summer coaching opportunities. Skyhawks offers paid positions. Work hours range from half-day to… VSA Resorts VSA Resorts is a family of three family vacation resorts in Virginia Beach, VA. Minimum age to apply is generally 18 years old. If you are under 18 years of age, you must provide proof of your eligibility… Burger Street Founded in 1985, Burger Street is a family owned fast food restaurant in Texas and Oklahoma. You must be at least 16 years old to apply jobs at Burger Street. Burger Street Job Application To apply hourly jobs… Bob Evans Founded in 1948, Bob Evans is chain of owned restaurants, not franchised, with over 500 locations in 19 states. You must be at least 16 years of age to apply jobs at Bob Evans (and minimum 18 years… Black-eyed Pea Founded in 1975, Black-eyed Pea is restaurant chain located in Texas and Colorado. Minimum age to apply jobs at Black-eyed Pea is generally 16 years old. You can apply jobs as a cook, server, dishwasher, or greeter/cashier. Black-eyed… Black Angus Steakhouse Founded in 1964, Black Angus Steakhouse is a restaurant chain specializing in steak. Minimum age to apply jobs at Black Angus Steakhouse is 16 years old (but only with 2 years restaurant kitchen experience). You can apply jobs… Big Boy Started as a small hamburger stand in 1935, Big Boy now has over 70 locations in the U.S. -

Sampling of Area Food, Shopping, and Activities

Veterinary Medical Center (614) 292-3551 Sampling of Area Food, Shopping, and Activities Lennox Town Center Restaurants on 777 Kinnear Road .69 miles 1 minute Olentangy River Road South Go west on Vernon Tharp Street. Turn left onto John Go west on Vernon Tharp Street. Turn left onto John Herrick Drive. Go to the first light and turn right onto Herrick Drive. Go to the first light and turn right onto Olentangy River Road. Go straight into Lennox Town Olentangy River Road. At the light turn left which is Center. the continuation of Olentangy River Road. Starbucks 1.01 miles 2 minutes Food: Wendy’s and Tim Hortons 1.1 miles 2 minutes Bravo! Cucina Italiana Bob Evans 1.13 miles 2 minutes Champps Americana (varied menu) Cap City Diner 1.35 miles 3 minutes Cup O’Joe Columbus Fish Market 1.43 miles 3 minutes Johnny Rockets (1950’s hamburger joint) Restaurants on Lane Avenue Shopping: These restaurants are on Lane Avenue before you come Barnes & Noble Pet Co to The Shops on Lane Avenue (above) Bath & Body Works Staples Tai’s Asian Bistro 1285 West Lane Avenue Famous Footwear Target (south side of the road) Men’s Warehouse World Market Asian Noodles House 1288 West Lane Avenue Old Navy (north side of the road) Jersey Mike’s Subs 1293 West Lane Avenue Activity: AMC Movie Theatres (south side of the road) Piada (Italian) 1315 West Lane Avenue (south side of the road) The Shops on Lane Avenue Subway 1320 West Lane Avenue (north side of the road) 1585 West Lane Avenue 1.78 miles 4 minutes Tommy’s Pizza 1350 West Lane Avenue Go west on Vernon Tharp Street, Turn right onto John (north side of the road) Herrick Drive. -

Lisa Edelstein

Lisa Edelstein Mike Tattersfield CEO and President Einstein Noah Restaurant Group Dear Mr. Tattersfield, There are few things I enjoy more than a good bagel in the morning—or any time of the day, really. That's why I'm writing to you today urging you to consider adding vegan cream cheese options to your menus so that people who can't—or won't—consume dairy foods might still be able to enjoy a good bagel with shmear at your many establishments. You only need to walk down a grocery aisle to see the result of the growing demand for all dairy alternatives, including plant-based cream cheese. And then there are the changes in the restaurant industry: From the tofu options at Chipotle Mexican Grill and Moe's Southwest Grill to classic vegan burgers at Denny's, White Castle, Johnny Rockets, and Red Robin, the competition is responding to demand. Innovation is now where the trend is, including Gardein's vegan chicken at Darden's Yard House, Beyond Meat's vegan chicken at Tropical Smoothie Cafe, and vegan meatballs at IKEA. For dairy-free offerings, TCBY's and Ben & Jerry's almond milk frozen yogurts and ice creams, respectively, instantly became huge hits, and around 40 pizza chains now offer vegan cheese. The time is ripe for vegan cream cheese, as demonstrated by the growing success of—and shelf space for—spreads by companies such as Follow Your Heart, Tofutti, GO Veggie, Kite Hill, and Daiya. I hope your brands will soon join others in meeting the demand for exciting plant-based menu items.