Between “Small Arms Fire” and Support

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Frosty Neighbours? Unpacking Narratives of Afghanistan-Pakistan Relations

Transcript Frosty Neighbours? Unpacking Narratives of Afghanistan-Pakistan Relations Suddaf Chaudry Investigative Journalist and Documentary Producer Amil Khan Associate Fellow, Asia-Pacific Programme, Chatham House Sana Safi Journalist and Presenter, BBC Afghanistan Service Chair: Hameed Hakimi Research Associate, Asia-Pacific Programme and Europe Programme, Chatham House 03 December 2018 The views expressed in this document are the sole responsibility of the speaker(s) and participants, and do not necessarily reflect the view of Chatham House, its staff, associates or Council. Chatham House is independent and owes no allegiance to any government or to any political body. It does not take institutional positions on policy issues. This document is issued on the understanding that if any extract is used, the author(s)/speaker(s) and Chatham House should be credited, preferably with the date of the publication or details of the event. Where this document refers to or reports statements made by speakers at an event, every effort has been made to provide a fair representation of their views and opinions. The published text of speeches and presentations may differ from delivery. © The Royal Institute of International Affairs, 2018. 10 St James’s Square, London SW1Y 4LE T +44 (0)20 7957 5700 F +44 (0)20 7957 5710 www.chathamhouse.org Patron: Her Majesty The Queen Chairman: Stuart Popham QC Director: Dr Robin Niblett Charity Registration Number: 208223 2 Frosty Neighbours? Unpacking Narratives of Afghanistan-Pakistan Relations Hameed Hakimi Good afternoon everyone. Welcome to Chatham House. My name is Hameed Hakimi and I’m a Research Associate here. I’m very happy that you’re here because given the rain, we were expecting that would affect the turnout. -

Kuwait, Iran Discuss Means to Alleviate Regional Tensions Gibraltar Rejects US Demand to Seize Iranian Oil Tanker

THULHIJJA 18, 1440 AH MONDAY, AUGUST 19, 2019 28 Pages Max 47º Min 26º 150 Fils Established 1961 ISSUE NO: 17909 The First Daily in the Arabian Gulf www.kuwaittimes.net Kuwait joins celebrations Iceland commemorates first High-end rebrand makes life Lampard denied first win as 5 of ‘women humanitarians’ 15 glacier lost to climate change 21 sweet for Japan’s ‘ice farmers’ 28 Leicester draw at Chelsea Kuwait, Iran discuss means to alleviate regional tensions Gibraltar rejects US demand to seize Iranian oil tanker KUWAIT: Kuwait’s Deputy Prime Zarif said that during the talks, he Minister and Foreign Minister Sheikh stressed that Iran’s proposal for a region- Amir recovers, in Sabah Al-Khaled Al-Hamad Al-Sabah al dialogue forum and non-aggression held talks yesterday with his Iranian pact would eliminate the need to rely on counterpart Mohammad Javad Zarif on a foreign powers. Unlike its strained rela- good health now host of issues, including means of reduc- tions with Saudi Arabia and the United KUWAIT: HH the Amir ing tensions in the Gulf region. The dis- Arab Emirates, Iran maintains good ties Sheikh Sabah Al-Ahmad cussions between Sheikh Sabah Al- with Kuwait, which has acted as mediator Al-Jaber Al-Sabah has Khaled and Zarif dealt with cooperation to improve ties between Tehran and Arab recovered from a setback between the two friendly countries, latest Gulf states. and is in good health regional events and ways to ease tensions Meanwhile, Gibraltar yesterday reject- now, Deputy Minister of in the Gulf. The talks also addressed ed a US demand to seize an Iranian oil Amiri Diwan confirmed means to ensure free navigation in this tanker at the center of a diplomatic dis- yesterday. -

Swahili Forum 13 (2006): Special Issue “Lugha Ya Mitaani in Tanzania”

SSWWAAHHIILLII FFOORRUUMM 1133 Edited by: Rose Marie Beck, Lutz Diegner, Clarissa Dittemer, Thomas Geider, Uta Reuster-Jahn SPECIAL ISSUE LUGHA YA MITAANI IN TANZANIA THE POETICS AND SOCIOLOGY OF A YOUNG URBAN STYLE OF SPEAKING WITH A DICTIONARY COMPRISING 1100 WORDS AND PHRASES Uta Reuster-Jahn & Roland Kießling 2006 Department of Anthropology and African Studies Johannes Gutenberg University Mainz, Germany ISSN 1614-2373 SWAHILI FORUM 13 (2006): SPECIAL ISSUE “LUGHA YA MITAANI IN TANZANIA” Content 1. Introduction: Lugha ya Mitaani 1 1.1 History of colloquial non-standard Swahili speech forms 1 1.2 Special forms of Lugha ya Mitaani 4 1.2.1 Campus Swahili 5 1.2.2 Secret codes derived from Swahili 5 1.2.3 Lugha ya vijana wa vijiweni 6 1.2.4 The language of daladalas 8 1.3 Overview of the article 9 2. Methodology 10 2.1 Field research 10 2. 2 Acknowledgements 12 2. 3 The making of the dictionary 12 3. Sociolinguistics of Lugha ya Mitaani 13 3.1 Lugha ya Mitaani as youth language 13 3.2 Knowledge, use and attitudes 14 3.3 Diachronic aspects of Lugha ya Mitaani 17 4. Lexical elaboration 18 4.1 Humans and social relations 20 4.1.1 Humans 20 4.1.2 Women 21 4.1.3 Men 23 4.1.4 Homosexuals 23 UTA REUSTER-JAHN & ROLAND KIEßLING 4.1.5 Social relationship 24 4.1.6 Social status 24 4.2 Communication 24 4.3 Body & Appearance 25 4.4 Economy, Money & Occupation 26 4.5 Sex 27 4.6 Drugs & Alcohol 28 4.7 Movement & Vehicles 28 4.8 Evaluative terms 29 4.9 Experience 30 4.10 Trouble & Violence 30 4.11 Crime & Police 30 4.12 Food 31 4.13 Disease 31 4.14 Geography & Place 32 4.15 Education 32 4.16 Sports 33 4.17 Weapons 33 4.18 Cultural innovation 33 4.19 Time 33 5. -

Youth Ambassador Program

Youth Ambassador Program Session 3: Promote Gender Equality & Empower Women (part 1) CHIME IN Youth Ambassador Program-Session 3-Created by Kelly Sullivan Walden 1 Table of Contents: SDG 5: Achieve gender equality and empower all women and girls. ! Inspirational Quotes p. 3 ! Session Overview: Purpose, Payoff, Process p. 4 ! Section 1: Featured SDG-Sustainable Development Goal p. 5-7 o Part 1: SDG 5 Overview " SDG 5 Targets o Part 2: Inquiry into SDG 5—Past (Problem) & Present (Progress) o Part 3: SDG Hero—Rula Ghani o Must See Videos ! Section 2: Hero’s Journey Stage 3—Refusal of the Call p. 8-10 ! Section 3: Leadership Modality—SLANT p. 11-12 ! Section 4: Action Plan/Homework p. 13 ! Section 5: Resources (books, videos, websites) p. 14 CHIME IN Youth Ambassador Program-Session 3-Created by Kelly Sullivan Walden 2 Inspirational Quotes for the Month: “Women hold up half the sky” ~ Mao Zedong “A woman is the full circle. Within her is the power to create, nurture and transform.” ~Diane Mariechild “Ensuring gender equality and empowering women in all respects are required to combat poverty, hunger and disease and to ensure sustainable development. The limited progress in empowering women and achieving gender equality is a pervasive shortcoming that extends beyond the goal itself” ~Sha Zukang UN Under-Secretary for Economic & Social Affairs 2008. “When a woman rises up in glory, her energy is magnetic and her sense of possibility contagious.” ~Marianne Williamson: A Woman's Worth CHIME IN Youth Ambassador Program-Session 3-Created by Kelly Sullivan Walden 3 Session Three Overview (Purpose, Payoff, and Process) Purpose: Our third session is to gain an overview of SDG 5: Achieve gender equality and empower all women and girls, with regards to the past (problem) and the present (progress). -

World Service Listings for 8 – 14 May 2021 Page 1 of 16

World Service Listings for 8 – 14 May 2021 Page 1 of 16 SATURDAY 08 MAY 2021 A short walk in the Russian woods Producer: Ant Adeane Another chance to hear Oleg Boldyrev of BBC Russian SAT 01:00 BBC News (w172xzjhw8w2cdg) enjoying last year's Spring lockdown in the company of fallen The latest five minute news bulletin from BBC World Service. trees, fungi, and beaver dams. SAT 05:50 More or Less (w3ct2djx) Finding Mexico City’s real death toll Image: 'Open Jirga' presenter Shazia Haya with all female SAT 01:06 Business Matters (w172xvq9r0rzqq5) audience in Kandahar Mexico City’s official Covid 19 death toll did not seem to President Biden insists US is 'on the right track' despite lower Credit: BBC Media Action reflect the full extent of the crisis that hit the country in the job numbers spring of 2020 - this is according to Laurianne Despeghel and Mario Romero. These two ordinary citizens used publicly The US economy added 266,000 jobs in April, far fewer than SAT 03:50 Witness History (w3ct1wyg) available data to show that excess deaths during the crisis - economists had predicted. President Biden has said his Surviving Guantanamo that’s the total number of extra deaths compared to previous economic plan is working despite the disappointing numbers. years - was four times higher than the confirmed Covid 19 We get analysis from Diane Swonk, chief economist at After 9/11 the USA began a programme of 'extraordinary deaths. accountancy firm Grant Thornton in Chicago. rendition', moving prisoners between countries without legal Also in the programme, Kai Ryssdal from our US partners representation. -

World Service Listings for 2 – 8 January 2021 Page 1 of 15 SATURDAY 02 JANUARY 2021 Arabic’S Ahmed Rouaba, Who’S from Algeria, Explains Why This with Their Heritage

World Service Listings for 2 – 8 January 2021 Page 1 of 15 SATURDAY 02 JANUARY 2021 Arabic’s Ahmed Rouaba, who’s from Algeria, explains why this with their heritage. cannon still means so much today. SAT 00:00 BBC News (w172x5p7cqg64l4) To comment on these stories and others we are joined on the The latest five minute news bulletin from BBC World Service. Remedies for the morning after programme by Emma Bullimore, a British journalist and Before coronavirus concerns in many countries, this was the broadcaster specialising in the arts, television and entertainment time of year for parties. But what’s the advice for the morning and Justin Quirk, a British writer, journalist and culture critic. SAT 00:06 BBC Correspondents' Look Ahead (w3ct1cyx) after, if you partied a little too hard? We consult Oleg Boldyrev BBC correspondents' look ahead of BBC Russian, Suping of BBC Chinese, Brazilian Fernando (Photo : Indian health workers prepare for mass vaccination Duarte and Sharon Machira of BBC Nairobi for their local drive; Credit: EPA/RAJAT GUPTA) There were times in 2020 when the world felt like an out of hangover cures. control carousel and we could all have been forgiven for just wanting to get off and to wait for normality to return. Image: Congolese house at the shoreline of Congo river SAT 07:00 BBC News (w172x5p7cqg6zt1) Credit: guenterguni/Getty Images The latest five minute news bulletin from BBC World Service. But will 2021 be any less dramatic? Joe Biden will be inaugurated in January but will Donald Trump have left the White House -

Broucher Final Withabstract.Pdf

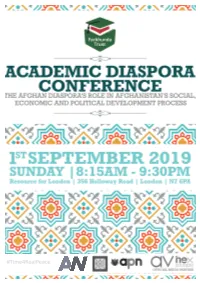

SPEAKERS | Rahela Sidiqi is the Founding Director of Farkhunda Trust for Afghan Women's Education. She is the former Senior Advisor of Afghanistan Civil Service Commission and Senior Social Development Advisor of UN- Habitat Afghanistan. Since 1993, she has worked as a women's rights activist at the grassroots and policy levels in Afghanistan. She completed her BSc in Agriculture from Kabul University and her MA in Social Development Sustainable Livelihood from Reading University UK. Said T. Jawad is currently the Ambassador of Afghanistan to the United Kingdom. He has previously served as Chief of Staff to the President of Afghanistan (2001 to 2003), Afghanistan’s Ambassador to the United States, Mexico, Brazil, Columbia and Argentina (2003-2010), the Senior Political and Foreign Policy Advisor to the Chief Executive of Afghanistan (2015-2017), the Chief Executive Officer of Capitalize LLC, a global strategic advisory firm headquartered in Washington, DC (2010-2017), the Chairman of the Foundation for Afghanistan (2004-2014); and as a Global Political Strategist and Senior Counselor at APCO Worldwide (2010-2017). ACADEMIC DIASPORA CONFERENCE 2019 | LONDON SPEAKERS | Shinkai Karokhail has been a Member of Parliament for 11 years at Lower House in Afghanistan. She is long life women right activist. Mrs Karokhail was Ambassador of Afghanistan in Canada, Director of AWEC, and initiator of Campaign “lets fight against Cancer” along with other activists, established Women Parliamentary Caucus, that led to development of NAPWA. She was part of the team for drafting several laws that affect women rights i.e. Elimination of Violence Against Women Law. Miss Karokhail received several national international prestige’s’ awards. -

Happy International Women's

See Inside Quote of the Week 2. Personal Essays 6. Star Related “Do not wait for leaders; do 3. Short Story 7. Literary it alone, person to person." 4-5. News 8. Interview - Mother Teresa Saturday, March 04, 2017 Vol. 2, No. 67 Star Educational Society Weekly Interstellar (adjective): situated or occurring between the stars; conducted, or existing between two or more stars Happy International Women’s Day 10 inspirational quotes from Afghan women and our friends at Free Women Writers http://www.freewomenwriters.org/10inspirationalquotesbyafghanwomen/ his International Women’s Day, and the world a better place. Every week ity in many parts of the country, Afghan push their country forward. Here are we are celebrating the wisdom a new story of horrifying violence against women continue to be imprisoned for ten powerful quotes from some of these and resilience of ten Afghan women is uncovered in Afghanistan and being raped, falling in love or marrying women that will motivate you to rededi- women who are using their the public lashings of women by Taliban by choice. Despite all this, the women cate yourself to gender-equality. T voices to make Afghanistan seem to have become a reoccurring real- of Afghanistan are risking their lives to 1. Sonita Alizadeh, Rapper 2. Zarghuna Kargar, Journalist and Author 3. Mahnaz Rezaie, Writer and Ac- 4. Humira Saqib, Activist and Director of 5. Sahraa Karimi, Filmmaker and Activist of Dear Zari tivist Afghan Women’s News Agency “We, Afghan women, must “To the women of my be- “Afghan women are no longer silent. -

BBC World Service – Written Evidence (AFG0015)

BBC World Service – Written evidence (AFG0015) International Relations and Defence Committee inquiry into The UK and Afghanistan September 2020 Introduction BBC World Service provides trusted news to radio, TV and digital audiences around the world in 42 languages including English. It is chiefly funded by the UK Licence Fee with additional funding of £86m a year coming from Government in the form of a Grant channelled via the Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office which has enabled the biggest expansion of the World Service since the 1940s. The World Service’s expansion (known as the World 2020 programme) included the launch of 12 new language services aimed at Nigeria, Ethiopia & Eritrea, India, Serbia and the Korean peninsula, enhanced programming in English, Arabic and Russian and the opening of new bureaux in Nairobi, Lagos and Delhi. Government funding has been confirmed up until September 2021 – funding beyond that point will be decided as part of the Comprehensive Spending Review (CSR). A large percentage of the additional funding the World Service receives from the Government is classed as Official Development Assistance (ODA). As well as providing impartial, accurate and independent news wherever there is a need due to media freedom restrictions or lack of means of access, the World Service plays a role in holding power to account, offering insight and fresh perspective during conflicts and as a defence against fake news and disinformation. This year’s Global Audience Measure1 showed that BBC’s news services now reach 438m people across the globe each week, an increase of 13% on last year. In Afghanistan, the seventh largest market for the BBC outside the UK, the BBC reaches 11.4m people every week – over 50% of the adult population – via the BBC Afghan service in Dari and Pashto, BBC Persian, BBC Uzbek as well as via commercially funded BBC World News TV and bbc.com/news. -

World Service Listings for 13 – 19 March 2021 Page 1 of 16

World Service Listings for 13 – 19 March 2021 Page 1 of 16 SATURDAY 13 MARCH 2021 SAT 02:30 BBC News Summary (w172x5q5g46p7f5) SAT 05:06 BBC OS Conversations (w3ct19zd) The latest two minute news summary from BBC World Service. Coronavirus: Resilience during a year of the pandemic SAT 00:00 BBC News (w172x5pc0dlzmnj) The latest five minute news bulletin from BBC World Service. One year ago, the World Health Organisation announced that SAT 02:32 Stumped (w3cszhkn) Covid19 was spreading across different countries at such an Haynes: Time to immortalise women’s cricket stars alarming rate that it needed to be classed as a pandemic. SAT 00:06 The Real Story (w3cszcpd) How dangerous are deepfakes? We reflect on the India/England test match series, discuss the It’s been a challenging year for everyone and host Nuala potential of England squad rotation during the Ashes and McGovern shares conversations with people who perhaps don’t When a series of chillingly convincing Tom Cruise deepfakes preview India against New Zealand in the Test Championship always receive public recognition for their work or actions. This went viral on TikTok this month, it brought home how fast final. includes one of the researchers who helped make the first synthetic media technology is evolving. Deepfakes are like vaccine to be approved for use around the world and two of the photoshop for video – using a form of artificial intelligence Plus the team will be joined by Australia women’s Vice-Captain volunteers who took part in successful vaccine trials. called deep learning to create a realistic depiction of fake Rachael Haynes after Cricket Australia announced that they are events. -

Globalincidentmap.Com Open Source IED Report IED Explosions, Bomb Threats, Scares, Hoaxes, Thefts of Explosives, and Other Explosive Plots 11-08-2011 – 11-18-2011

GlobalIncidentMap.Com Open Source IED Report IED Explosions, Bomb Threats, Scares, Hoaxes, Thefts Of Explosives, And Other Explosive Plots 11-08-2011 – 11-18-2011 • Bomb Incidents/Explosives/ Hoax Devices 2011-11-18 | United States, Shreveport, LA | [ktbs.com] LOUISIANA - Boys arrested after detonating acid bomb "A pair of 12-year-olds have been arrested in Shreveport for assembling and then detonating two makeshift "acid bombs" using materials they just bought at a discount store." Read the full article: http://www.ktbs.com/news/29805078/detail.html | To view this incident at GlobalIncidentMap.com visit : http://www.globalincidentmap.com/eventdetail.php?ID=64925 2011-11-18 | United States, Horsham, PA | [PhillyBurbs.com] PENNSYLVANIA - Man held in bomb threat at Horsham pharmacy "A pharmacy was shut down and traffic jammed after what appeared to be a bomb was found in a car parked in a lot off Welsh Road in Horsham on Thursday evening." Read the full article: http://www.phillyburbs.com/news/local/the_intelligencer_news/man- held-in-bomb-threat-at-horsham-pharmacy/article_8ec561f6-a609-5c96- bf1b-9f1002bb1fcf.html#.TsaPCT1R63c | To view this incident at GlobalIncidentMap.com visit : http://www.globalincidentmap.com/eventdetail.php?ID=64924 1 GlobalIncidentMap.Com Open Source IED Report IED Explosions, Bomb Threats, Scares, Hoaxes, Thefts Of Explosives, And Other Explosive Plots 11-08-2011 – 11-18-2011 2011-11-18 | United States, Lansing, MI | [WILX.com] MICHIGAN - BREAKING NEWS: Police Investigating Bomb Threat "Several buildings in downtown -

Your Ad Here Your Ad Here

Eye on the News [email protected] Truthful, Factual and Unbiased Vol:X Issue No:212 Price: Afs.15 www.afghanistantimes.af www.facebook.com/ afghanistantimeswww.twitter.com/ afghanistantimes TUESDAY . MARCH 01 . 2016 -Hoot 11, 1394 HS Yo ur Yo ur ad ad he re he re 0778894038 KABUL: A new book authored by from former ISI director general, the wife a former operative of Paki- retired Lt-Gen Hamid Gul, which stan’s spy agency has once again also claims that Khawaja was very he said, adding that Afghan gov- made the claim that Nawaz Sharif close to Nawaz Sharif for some By Mansoor Faizy received money from al-Qaeda lead- time. The book claims that Abdul- ernment was committed and will- er Osama Bin Laden. The book, lah Azzam introduced Khawaja to ing to work jointly with China for KABUL: Afghanistan’s Nation- Khalid Khawaja: Shaheed-i-Aman, Bin Laden. Azzam, who is also securing mutual and regional inter- is authored by Shamama Khalid, the known as the ‘father of global ji- al Security Advisor Mohammad ests. Atmar welcomed the pro- Hanif Atmar on Monday met wife of former ISI operative Khalid had’, was a Palestinian Sunni. Az- posal of Fenghui that Afghanistan, Khawaja. “Chief of PML-N Mian zam raised funds and recruited ji- with the Chief of the Chinese Peo- China, Tajikistan, and Pakistan Mohammad Nawaz Sharif received hadis from the Arab world, known ple’s Liberation Army, Gen. Fang militaries should form a Joint Co- funding from Osama Bin Laden, as Afghan Arabs. A mentor of Bin Fenghui, at his office and request- ordination Mechanism for region- founder of Al-Qaeda, to contest elec- Laden, he is said to have persuad- ed Beijing for military assistance.