Learning Unethical Practices from a Co-Worker: the Peer Effect of Jose Canseco

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Designer Player

The Designer Player Rodrigo Villagomez Baseball is a multi-billion dollar entertainment industry. The modern age of American sports has seen to it that we no longer look at baseball as just "America's pastime." We must now see it as another corporation striving to produce a product that will be consumed by the populous. It is a corporation that produces the reluctant hero, a man who begrudgingly accepts the title "role model." These players are under intense pressure to continually be on top of their game. They are driven by relentless fans to achieve greater levels of strength and prowess. Consequentially, because of this pressure more professional baseball players are turning to performance-enhancing drugs, more specifically steroids, to aid them in their quest for greatness. Many believe that these drugs decrease the integrity of the players and ultimately the game itself. My opinion is that if it were not for the small percentage of players who have recently been found to use steroids, baseball would not be enjoying the success it does today. So really baseball should be thanking these players for actually keeping the game popular. Before this argument begins, let's first look at the clinical definition of a steroid. A steroid is "any group of organic compounds belonging to the general class of biochemicals called lipids, which are easily soluble in organic solvents and slightly soluble in water" (Dempsey). Now let's put it in terms that you and I can understand with the help of author Dayn Perry. "Testosterone has an androgenic, or masculizing, function and an anabolic, or tissue-building, function. -

Repeal of Baseball's Longstanding Antitrust Exemption: Did Congress Strike out Again?

Repeal of Baseball's Longstanding Antitrust Exemption: Did Congress Strike out Again? INTRODUCrION "Baseball is everybody's business."' We have just witnessed the conclusion of perhaps the greatest baseball season in the history of the game. Not one, but two men broke the "unbreakable" record of sixty-one home-runs set by New York Yankee great Roger Maris in 1961;2 four men hit over fifty home-runs, a number that had only been surpassed fifteen times in the past fifty-six years,3 while thirty-three players hit over thirty home runs;4 Barry Bonds became the only player to record 400 home-runs and 400 stolen bases in a career;5 and Alex Rodriguez, a twenty-three-year-old shortstop, joined Bonds and Jose Canseco as one of only three men to have recorded forty home-runs and forty stolen bases in a 6 single season. This was not only an offensive explosion either. A twenty- year-old struck out twenty batters in a game, the record for a nine inning 7 game; a perfect game was pitched;' and Roger Clemens of the Toronto Blue Jays won his unprecedented fifth Cy Young award.9 Also, the Yankees won 1. Flood v. Kuhn, 309 F. Supp. 793, 797 (S.D.N.Y. 1970). 2. Mark McGwire hit 70 home runs and Sammy Sosa hit 66. Frederick C. Klein, There Was More to the Baseball Season Than McGwire, WALL ST. J., Oct. 2, 1998, at W8. 3. McGwire, Sosa, Ken Griffey Jr., and Greg Vaughn did this for the St. -

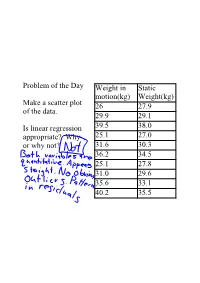

Problem of the Day Make a Scatter Plot of the Data. Is Linear Regression

Problem of the Day Weight in Static motion(kg) Weight(kg) Make a scatter plot 26 27.9 of the data. 29.9 29.1 Is linear regression 39.5 38.0 appropriate? Why 25.1 27.0 or why not? 31.6 30.3 36.2 34.5 25.1 27.8 31.0 29.6 35.6 33.1 40.2 35.5 Salary(in Problem of the Day Player Year millions) Nolan Ryan 1980 1.0 Is it appropriate to use George Foster 1982 2.0 linear regression Kirby Puckett 1990 3.0 to predict salary Jose Canseco 1991 4.7 from year? Roger Clemens 1996 5.3 Why or why not? Ken Griffey, Jr 1997 8.5 Albert Belle 1997 11.0 Pedro Martinez 1998 12.5 Mike Piazza 1999 12.5 Mo Vaughn 1999 13.3 Kevin Brown 1999 15.0 Carlos Delgado 2001 17.0 Alex Rodriguez 2001 22.0 Manny Ramirez 2004 22.5 Alex Rodriguez 2005 26.0 Chapter 10 ReExpressing Data: Get It Straight! Linear Regressioneasiest of methods, how can we make our data linear in appearance Can we reexpress data? Change functions or add a function? Can we think about data differently? What is the meaning of the yunits? Why do we need to reexpress? Methods to deal with data that we have learned 1. 2. Goal 1 making data symmetric Goal 2 make spreads more alike(centers are not necessarily alike), less spread out Goal 3(most used) make data appear more linear Goal 4(similar to Goal 3) make the data in a scatter plot more spread out Ladder of Powers(pg 227) Straightening is good, but limited multimodal data cannot be "straightened" multiple models is really the only way to deal with this data Things to Remember we want linear regression because it is easiest (curves are possible, but beyond the scope of our class) don't choose a model based on r or R2 don't go too far from the Ladder of Powers negative values or multimodal data are difficult to reexpress Salary(in Player Year Find an appropriate millions) Nolan Ryan 1980 1.0 linear model for the George Foster 1982 2.0 data. -

Fair Ball! Why Adjustments Are Needed

© Copyright, Princeton University Press. No part of this book may be distributed, posted, or reproduced in any form by digital or mechanical means without prior written permission of the publisher. CHAPTER 1 Fair Ball! Why Adjustments Are Needed King Arthur’s quest for it in the Middle Ages became a large part of his legend. Monty Python and Indiana Jones launched their searches in popular 1974 and 1989 movies. The mythic quest for the Holy Grail, the name given in Western tradition to the chal- ice used by Jesus Christ at his Passover meal the night before his death, is now often a metaphor for a quintessential search. In the illustrious history of baseball, the “holy grail” is a ranking of each player’s overall value on the baseball diamond. Because player skills are multifaceted, it is not clear that such a ranking is possible. In comparing two players, you see that one hits home runs much better, whereas the other gets on base more often, is faster on the base paths, and is a better fielder. So which player should rank higher? In Baseball’s All-Time Best Hitters, I identified which players were best at getting a hit in a given at-bat, calling them the best hitters. Many reviewers either disapproved of or failed to note my definition of “best hitter.” Although frequently used in base- ball writings, the terms “good hitter” or best hitter are rarely defined. In a July 1997 Sports Illustrated article, Tom Verducci called Tony Gwynn “the best hitter since Ted Williams” while considering only batting average. -

Top Sluggers and Their Home Run Breakdowns

Best of Baseball Prospectus: 1996-2011 Part 1: Offense 6 APRIL 22, 2004 : http://bbp.cx/a/2795 HANK AARON'S HOME COOKING Top Sluggers and Their Home Run Breakdowns Jay Jaffe One of the qualities that makes baseball unique is its embrace of non-standard playing surfaces. Football fields and basketball courts are always the same length, but no two outfields are created equal. As Jay Jaffe explains via a look at Barry Bonds and the all-time home run leaderboard, a player’s home park can have a significant effect on how often he goes yard. It's been a couple of weeks since the 30th anniversary of Hank Aaron's historic 715th home run and the accompanying tributes, but Barry Bonds' exploits tend to keep the top of the all-time chart in the news. With homers in seven straight games and counting at this writing, Bonds has blown past Willie Mays at number three like the Say Hey Kid was standing still, which— congratulatory road trip aside—he has been, come to think of it. Baseball Prospectus' Dayn Perry penned an affectionate tribute to Aaron last week. In reviewing Hammerin' Hank's history, he notes that Aaron's superficially declining stats in 1968 (the Year of the Pitcher, not coincidentally) led him to consider retirement, but that historian Lee Allen reminded him of the milestones which lay ahead. Two years later, Aaron became the first black player to cross the 3,000 hit threshold, two months ahead of Mays. By then he was chasing 600 homers and climbing into some rarefied air among the top power hitters of all time. -

Tml American - Single Season Leaders 1954-2016

TML AMERICAN - SINGLE SEASON LEADERS 1954-2016 AVERAGE (496 PA MINIMUM) RUNS CREATED HOMERUNS RUNS BATTED IN 57 ♦MICKEY MANTLE .422 57 ♦MICKEY MANTLE 256 98 ♦MARK McGWIRE 75 61 ♦HARMON KILLEBREW 221 57 TED WILLIAMS .411 07 ALEX RODRIGUEZ 235 07 ALEX RODRIGUEZ 73 16 DUKE SNIDER 201 86 WADE BOGGS .406 61 MICKEY MANTLE 233 99 MARK McGWIRE 72 54 DUKE SNIDER 189 80 GEORGE BRETT .401 98 MARK McGWIRE 225 01 BARRY BONDS 72 56 MICKEY MANTLE 188 58 TED WILLIAMS .392 61 HARMON KILLEBREW 220 61 HARMON KILLEBREW 70 57 TED WILLIAMS 187 61 NORM CASH .391 01 JASON GIAMBI 215 61 MICKEY MANTLE 69 98 MARK McGWIRE 185 04 ICHIRO SUZUKI .390 09 ALBERT PUJOLS 214 99 SAMMY SOSA 67 07 ALEX RODRIGUEZ 183 85 WADE BOGGS .389 61 NORM CASH 207 98 KEN GRIFFEY Jr. 67 93 ALBERT BELLE 183 55 RICHIE ASHBURN .388 97 LARRY WALKER 203 3 tied with 66 97 LARRY WALKER 182 85 RICKEY HENDERSON .387 00 JIM EDMONDS 203 94 ALBERT BELLE 182 87 PEDRO GUERRERO .385 71 MERV RETTENMUND .384 SINGLES DOUBLES TRIPLES 10 JOSH HAMILTON .383 04 ♦ICHIRO SUZUKI 230 14♦JONATHAN LUCROY 71 97 ♦DESI RELAFORD 30 94 TONY GWYNN .383 69 MATTY ALOU 206 94 CHUCK KNOBLAUCH 69 94 LANCE JOHNSON 29 64 RICO CARTY .379 07 ICHIRO SUZUKI 205 02 NOMAR GARCIAPARRA 69 56 CHARLIE PEETE 27 07 PLACIDO POLANCO .377 65 MAURY WILLS 200 96 MANNY RAMIREZ 66 79 GEORGE BRETT 26 01 JASON GIAMBI .377 96 LANCE JOHNSON 198 94 JEFF BAGWELL 66 04 CARL CRAWFORD 23 00 DARIN ERSTAD .376 06 ICHIRO SUZUKI 196 94 LARRY WALKER 65 85 WILLIE WILSON 22 54 DON MUELLER .376 58 RICHIE ASHBURN 193 99 ROBIN VENTURA 65 06 GRADY SIZEMORE 22 97 LARRY -

Baseball Classics All-Time All-Star Greats Game Team Roster

BASEBALL CLASSICS® ALL-TIME ALL-STAR GREATS GAME TEAM ROSTER Baseball Classics has carefully analyzed and selected the top 400 Major League Baseball players voted to the All-Star team since it's inception in 1933. Incredibly, a total of 20 Cy Young or MVP winners were not voted to the All-Star team, but Baseball Classics included them in this amazing set for you to play. This rare collection of hand-selected superstars player cards are from the finest All-Star season to battle head-to-head across eras featuring 249 position players and 151 pitchers spanning 1933 to 2018! Enjoy endless hours of next generation MLB board game play managing these legendary ballplayers with color-coded player ratings based on years of time-tested algorithms to ensure they perform as they did in their careers. Enjoy Fast, Easy, & Statistically Accurate Baseball Classics next generation game play! Top 400 MLB All-Time All-Star Greats 1933 to present! Season/Team Player Season/Team Player Season/Team Player Season/Team Player 1933 Cincinnati Reds Chick Hafey 1942 St. Louis Cardinals Mort Cooper 1957 Milwaukee Braves Warren Spahn 1969 New York Mets Cleon Jones 1933 New York Giants Carl Hubbell 1942 St. Louis Cardinals Enos Slaughter 1957 Washington Senators Roy Sievers 1969 Oakland Athletics Reggie Jackson 1933 New York Yankees Babe Ruth 1943 New York Yankees Spud Chandler 1958 Boston Red Sox Jackie Jensen 1969 Pittsburgh Pirates Matty Alou 1933 New York Yankees Tony Lazzeri 1944 Boston Red Sox Bobby Doerr 1958 Chicago Cubs Ernie Banks 1969 San Francisco Giants Willie McCovey 1933 Philadelphia Athletics Jimmie Foxx 1944 St. -

2017 Information & Record Book

2017 INFORMATION & RECORD BOOK OWNERSHIP OF THE CLEVELAND INDIANS Paul J. Dolan John Sherman Owner/Chairman/Chief Executive Of¿ cer Vice Chairman The Dolan family's ownership of the Cleveland Indians enters its 18th season in 2017, while John Sherman was announced as Vice Chairman and minority ownership partner of the Paul Dolan begins his ¿ fth campaign as the primary control person of the franchise after Cleveland Indians on August 19, 2016. being formally approved by Major League Baseball on Jan. 10, 2013. Paul continues to A long-time entrepreneur and philanthropist, Sherman has been responsible for establishing serve as Chairman and Chief Executive Of¿ cer of the Indians, roles that he accepted prior two successful businesses in Kansas City, Missouri and has provided extensive charitable to the 2011 season. He began as Vice President, General Counsel of the Indians upon support throughout surrounding communities. joining the organization in 2000 and later served as the club's President from 2004-10. His ¿ rst startup, LPG Services Group, grew rapidly and merged with Dynegy (NYSE:DYN) Paul was born and raised in nearby Chardon, Ohio where he attended high school at in 1996. Sherman later founded Inergy L.P., which went public in 2001. He led Inergy Gilmour Academy in Gates Mills. He graduated with a B.A. degree from St. Lawrence through a period of tremendous growth, merging it with Crestwood Holdings in 2013, University in 1980 and received his Juris Doctorate from the University of Notre Dame’s and continues to serve on the board of [now] Crestwood Equity Partners (NYSE:CEQP). -

Probable Starting Pitchers 31-31, Home 15-16, Road 16-15

NOTES Great American Ball Park • 100 Joe Nuxhall Way • Cincinnati, OH 45202 • @Reds • @RedsPR • @RedlegsJapan • reds.com 31-31, HOME 15-16, ROAD 16-15 PROBABLE STARTING PITCHERS Sunday, June 13, 2021 Sun vs Col: RHP Tony Santillan (ML debut) vs RHP Antonio Senzatela (2-6, 4.62) 700 wlw, bsoh, 1:10et Mon at Mil: RHP Vladimir Gutierrez (2-1, 2.65) vs LHP Eric Lauer (1-2, 4.82) 700 wlw, bsoh, 8:10et Great American Ball Park Tue at Mil: RHP Luis Castillo (2-9, 6.47) vs LHP Brett Anderson (2-4, 4.99) 700 wlw, bsoh, 8:10et Wed at Mil: RHP Tyler Mahle (6-2, 3.56) vs RHP Freddy Peralta (6-1, 2.25) 700 wlw, bsoh, 2:10et • • • • • • • • • • Thu at SD: LHP Wade Miley (6-4, 2.92) vs TBD 700 wlw, bsoh, 10:10et CINCINNATI REDS (31-31) vs Fri at SD: RHP Tony Santillan vs TBD 700 wlw, bsoh, 10:10et Sat at SD: RHP Vladimir Gutierrez vs TBD 700 wlw, FOX, 7:15et COLORADO ROCKIES (25-40) Sun at SD: RHP Luis Castillo vs TBD 700 wlw, bsoh, mlbn, 4:10et TODAY'S GAME: Is Game 3 (2-0) of a 3-game series vs Shelby Cravens' ALL-TIME HITS, REDS CAREER REGULAR SEASON RECORD VS ROCKIES Rockies and Game 6 (3-2) of a 6-game homestand that included a 2-1 1. Pete Rose ..................................... 3,358 All-Time Since 1993: ....................................... 105-108 series loss to the Brewers...tomorrow night at American Family Field, 2. Barry Larkin ................................... 2,340 At Riverfront/Cinergy Field: ................................. -

NABF Tournament News 09.Indd

November 1, 2009 • Bowie, Maryland • Price $1.00 95th Year Graduate of the Year NABF Graduates of the Year NABF Honors 1968 Bill Freehan (Detroit Tigers) 1969 Pete Rose (Cincinnati Reds) 1970 Bernie Carbo (Cincinnati Reds) 1971 Ted Simmons (St. Louis Cardinals) Zack Greinke 1972 John Mayberry (Kansas City The National Amateur Base- Royals) 1973 Sal Bando (Oakland Athletics) ball Federation is honoring Kan- 1974 Jim Wynn (Los Angeles Dodgers) sas City Royals pitcher Zack 1975 Frank Tanana (California Angels) Greinke is its 2009 Graduate of 1976 Rick Manning (Cleveland Indians) 1977 Kenton Tekulve (Pittsburgh the Year. Pirates) Greinke played on the NABF 1978 Lary Sorenson (Milwaukee 18 and under National Team in Brewers) 1979 Willie Horton (Seattle Mariners) 2001 in Joplin, Missouri — the 1980 Britt Burns (Chicago White Sox) fi rst year USA Baseball was in- 1981 Tom Paciorek (Seattle Mariners) 14 and under NABF Regional Classic Tournament action at Detwiler Park in Toledo, volved in the Tournament of 1982 Leon Durham (Chicago Cubs) Ohio (NABF photo by Harold Hamilton/www.hehphotos.lifepics.com). 1983 Robert Bonnell (Toronto Blue Stars. Jays) "He came to us 1984 Jack Perconte (Seattle Mariners) as a shortstop and 1985 John Franco (Cincinnati Reds) 2009 NABF Annual Meeting 1986 Jesse Barfi eld (Toronto Blue a possible pitcher," Jays) says NABF board 1987 Brian Fletcher (Texas Rangers) to be in Annapolis, Maryland member and na- 1988 Allen L. Anderson (Minnesota Twins) tional team busi- The 95th Annual Meeting of 1989 Dave Dravecky (San Fransisco ness manager Lou Tiberi. Giants) the National Amateur Baseball Greinke played shortstop and 1990 Barry Larkin (Cincinnati Reds) Federation will be Thursday, 1991 Steve Farr (New York Yankees) hit fourth during the fi rst four November 5 to Sunday, Novem- 1992 Marquies Grissom (Montreal games of the TOS. -

A Long, Strange Trip to Cubs World Series

A long, strange trip to Cubs World Series By George Castle, CBM Historian Posted Friday, October 28, 2016 The Cubs appear a thoroughly dominant team with no holes, and certainly no “Cubbie Occurrences,” in playing the Cleveland Indi- ans in the generations-delayed World Series. But, to steal the millionth time from a song- writer, what a long, strange trip is has been. Truth is stranger than fiction in the Cubs Universe. On my own 45-year path of watch- ing games and talking to the newsmakers at Wrigley Field, I have been a witness to: Burt Hooton slugged a grand-slam homer off Tom “Terrific” Seaver in an 18- 5 pounding of the New York Mets in 1972. Hillary Clinton throws out first ball at Wrigley Field in 1994. On my 19th birthday, May 27, 1974, lefty Ken “Failing” Frailing pitched a complete-game 15-hitter in a 12-4 victory over the San Francisco Giants. A few weeks later, Rich Reuschel tossed a 12-hit shutout against the Lumber Com- pany Pittsburgh Pirates. In mid-Aug. 1974, the Dodgers had 24 hits by the sixth inning in an 18-8 victory over the Cubs. Apparently peeved, the Pirates in late 1975 racked up the most lopsided shutout in history, 22-0 over the Cubs. Reuschel started and gave up eight runs in the first. Brother Paul Reuschel mopped up in the ninth. Rennie Stennett went 7-for-7. Amazingly, less than a month previously, the Reuschels teamed for the only all- brother shutout in history in a 7-0 victory over the Dodgers (also witnessed here). -

LINE DRIVES the NATIONAL COLLEGIATE BASEBALL WRITERS NEWSLETTER (Volume 48, No

LINE DRIVES THE NATIONAL COLLEGIATE BASEBALL WRITERS NEWSLETTER (Volume 48, No. 3, Apr. 17, 2009) The President’s Message By NCBWA President Joe Dier NCBWA Membership: With the 2008-09 hoops season now in the record books, the collegiate spotlight is focusing more closely on the nation’s baseball diamonds. Though we’re heading into the final month of the season, there are still plenty of twists and turns ahead on the road to Omaha and the 2009 NCAA College World Series. The NCAA will soon be announcing details of next month’s tournament selection announcements naming the regional host sites (May 24) and the 64-team tournament field (May 25). To date, four different teams have claimed the top spot in the NCBWA’s national Division I polls --- Arizona State, Georgia, LSU, and North Carolina. Several other teams have graced the No. 1 position in other national polls. The NCAA’s mid-April RPI listing has Cal State Fullerton leading the 301-team pack, with 19 teams sporting 25-win records through games of April 12. For the record, New Mexico State tops the wins list with a 30-6 mark. As the conference races heat up from coast to coast, the NCBWA will begin the process for naming its All- America teams and the Divk Howser Trophy (see below). We will have a form going out to conference offices and Division I independents in coming days. Last year’s NCBWA-selected team included 56 outstanding baseball athletes, and we want to have the names of all deserving players on the table for consideration for this year’s awards.