Penile Plethysmography

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Aguide to Evidence-Based Practices

A GUIDE TO EVIDENCE-BASED PRACTICES for INDIVIDUALS WITH DEVELOPMENTAL DISABILITIES This report was produced with the support of the Saginaw County Community Mental Health Authority May 2009 Compiled by Barbara Glassheim This document may not be reproduced or distributed without the express permission of SCCMHA A GUIDE TO EVIDENCE-BASED PRACTICES FOR INDIVIDUALS WITH DEVELOPMENTAL DISABILITIES V. 1.0 TABLE OF CONTENTS FORWARD ............................................................................................................... 1 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ............................................................................................. 2 INTRODUCTION ....................................................................................................... 4 AN OVERVIEW OF EVIDENCE-BASED PRACTICE CONCEPTS ........................................... 7 CULTURAL CONSIDERATIONS ................................................................................. 10 MALTREATMENT ................................................................................................ 10 WOMEN ............................................................................................................. 11 OLDER ADULTS .................................................................................................. 11 ETHNIC GROUPS ................................................................................................ 12 DEAF CULTURE .................................................................................................. 13 EMPOWERMENT -

Procedure to Validate Sexual Stimuli: Reliability and Validity of a Set of Sexual Stimuli in a Sample of Young Colombian Heterosexual Males

Int. J. of Pysch. Res, Vol. 10 (1) 18-24 2017 DOI 10.21500/20112084.2268 Procedure to Validate Sexual Stimuli: Reliability and Validity of a Set of Sexual Stimuli in a Sample of Young Colombian Heterosexual Males Procedimiento para Validar Est´ımulos Sexuales: Confiabilidad y Validacion´ de un Conjunto de Est´ımulos Sexuales en una Muestra de Jovenes´ Hombres Heterosexuales Colombianos Pablo Vallejo-Medina1*, Franklin Soler2, Mayra, Gomez-Lugo´ 1, Alejandro, Saavedra-Roa1, and Laurent, Marchal-Bertrand 1. Abstract Penile plethysmography – or phallometric assessment – is a very relevant evaluation for sexual health. The objective of this research is to suggest a guideline to validate sexual stimuli and validate a set of sexual stimuli to assess “normative” sexual behavior in Colombian young heterosexual men. Six videos of 3:15 minute-long were used. A total of 24 men were assessed. Objective sexual arousal, the International Index of Erectile Function-5, Self-Assessment Manikin, Multidimensional Scale to Assess Subjective Sexual Arousal and socio-psycho-sexual questions were used. The results showed three sexual excerpts which were clearly superior to the others – something discordant with the subjective opinion of researchers. These three sexual excerpts generated internally consistent measurements; moreover, good indicators of external validity have been observed with statistically significant differences as expected. Furthermore, with a small healthy Colombian young population, it has been shown that the three stimuli produce objective sexual arousal if used together. Resumen La pletimosgraf´ıa peneana - o la medicion´ falometrica´ - es una importante forma de evaluar la salud sexual. El objetivo de esta´ investigacion´ es sugerir un procedimiento para validar est´ımulos sexuales y validar un set de est´ımulos sexuales para evaluar comportamientos sexuales “normativos”, en formato de video, en hombres colombianos jovenes´ y heterosexuales. -

Castrating Pedophiles Convicted of Sex Offenses Against Children: New Treatment Or Old Punishment

SMU Law Review Volume 51 Issue 2 Article 4 1998 Castrating Pedophiles Convicted of Sex Offenses against Children: New Treatment or Old Punishment William Winslade T. Howard Stone Michele Smith-Bell Denise M. Webb Follow this and additional works at: https://scholar.smu.edu/smulr Recommended Citation William Winslade et al., Castrating Pedophiles Convicted of Sex Offenses against Children: New Treatment or Old Punishment, 51 SMU L. REV. 349 (1998) https://scholar.smu.edu/smulr/vol51/iss2/4 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Journals at SMU Scholar. It has been accepted for inclusion in SMU Law Review by an authorized administrator of SMU Scholar. For more information, please visit http://digitalrepository.smu.edu. CASTRATING PEDOPHILES CONVICTED OF SEX OFFENSES AGAINST CHILDREN: NEW TREATMENT OR OLD PUNISHMENT? William Winslade* T. Howard Stone** Michele Smith-Bell*** Denise M. Webb**** TABLE OF CONTENTS I. INTRODUCTION ........................................ 351 II. PEDOPHILIA AND ITS TREATMENT ................. 354 A. THE NATURE OF PEDOPHILIA ......................... 355 1. Definition of Pedophilia ........................... 355 2. Sex Offenses and Sex Offenders ................... 357 a. Incidence of Sex Offenses ..................... 357 b. Characteristics of and Distinctions Among Sex O ffenders ..................................... 360 B. ETIOLOGY AND TREATMENT .......................... 364 1. Etiology and Course of Pedophilia................. 364 2. Treatment ......................................... 365 a. Biological of Pharmacological Treatment ...... 366 * Program Director, Program on Legal & Ethical Issues in Correctional Health, In- stitute for the Medical Humanities, James Wade Rockwell Professor of Philosophy of Medicine, Professor of Preventive Medicine & Community Health, and Professor of Psy- chiatry & Behavioral Sciences, University of Texas Medical Branch, Galveston, Texas; Dis- tinguished Visiting Professor of Law, University of Houston Health Law & Policy Institute. -

IN the UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT for the NORTHERN DISTRICT of NEW YORK THOMAS M. ROLAND, III, Plaintiff, Civil Action No. V

Case 9:10-cv-00089-MAD-DEP Document 19 Filed 05/24/10 Page 1 of 82 IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE NORTHERN DISTRICT OF NEW YORK THOMAS M. ROLAND, III, Plaintiff, Civil Action No. v. 9:10-CV-0089 (GLS/DEP) FRANK WENZ, T.A.,1 Defendant. APPEARANCES: OF COUNSEL: FOR PLAINTIFF: THOMAS M. ROLAND, III, Pro Se 04-B-2754 Wende Correctional Facility P.O. Box 1187 Alden, NY 14004 FOR DEFENDANT: HON. ANDREW M. CUOMO ROGER W. KINSEY, ESQ. Attorney General of the Assistant Attorney General State of New York The Capitol Albany, NY 12224-0341 DAVID E. PEEBLES U.S. MAGISTRATE JUDGE 1 In plaintiff’s complaint the defendant is identified as “Frank Wench”. Defendant’s moving papers, however, reflect that the correct spelling of the defendant’s last name is “Wenz”. The clerk will therefore respectfully be requested to adjust the official court records in this case to reflect the correct spelling of the defendant’s name. Case 9:10-cv-00089-MAD-DEP Document 19 Filed 05/24/10 Page 2 of 82 REPORT AND RECOMMENDATION Plaintiff Thomas M. Roland, III, a New York State prison inmate who is proceeding pro se and in forma pauperis, has commenced this action pursuant to 42 U.S.C. § 1983 claiming deprivation of his civil rights. In his complaint, plaintiff maintains that during the period of his confinement he was assaulted by the defendant and forced to submit to a drug injection after informing medical personnel at the facility of his desire to ingest the medication being administered orally, claiming both a denial of due process as guaranteed by the Fourteenth Amendment and exposure to cruel and unusual punishment prohibited under the Eighth Amendment. -

Testing Sexual Orientation: a Scientific and Legal Analysis of Plethysmography in Asylum & Refugee Status Proceedings

TESTING SEXUAL ORIENTATION A Scientific and Legal Analysis of Plethysmography in Asylum & Refugee Status Proceedings December 2010 Testing Sexual Orientation: A Scientific and Legal Analysis of Plethysmography in Asylum & Refugee Status Proceedings ORAM – Organization for Refuge, Asylum & Migration San Francisco, California December 2010 This publication is a collaborative work of ORAM’s board of directors, staff, interns, and supporters. We are grateful to Ryan M. Rifkin, Synaptic and Davis Scholar at Tufts University, who spent hundreds of hours meticulously researching, documenting, and drafting all scientific facets of the paper. Thanks also to Mary A. Hutton, Kevin C. Lo, and Deidre A. Plant for their dedicated legal research, analysis and writing, and to Mana Barari, who coordinated the legal research. H. Jessica Kim integrated and assembled the materials into a cohesive whole and provided critical research, writing, and citation analysis. Rachel S. Levitan conducted advocacy and legal analysis, and Eddie Bruce-Jones provided case law translation. Natalie DeJarlais provided copy editing and proofreading, and Kaveh Gilman assisted with formatting and graphic design. Gisela Thater, Legal Officer at the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) Division of International Protection, gave critical analysis and feedback. Overall project management and editing were provided by Neil Grungras. Funding for this project was provided by the Open Society Foundations, building vibrant and tolerant democracies whose governments are accountable to their citizens. The contributors’ commitment to excellence and to refugee justice is our continuing inspiration! Copyright © 2010 ORAM – Organization for Refuge, Asylum & Migration This publication may be reproduced in whole or in part with appropriate attribution. -

Medical Policy

MEDICAL POLICY SUBJECT: ERECTILE DYSFUNCTION EFFECTIVE DATE: 09/16/99 REVISED DATE: 09/19/01, 09/26/02, 10/23/03, 09/23/04, 10/27/05, 10/26/06, 10/24/07, 10/23/08 ARCHIVED DATE: 10/28/09 EDITED DATE: 06/24/10, 6/24/11, 06/28/12, 06/27/13, POLICY NUMBER: 7.01.30 06/26/14 CATEGORY: Miscellaneous PAGE: 1 OF: 8 If the member's subscriber contract excludes coverage for a specific service it is not covered under that contract. In such cases, medical policy criteria are not applied. Medical policies apply to commercial and Medicaid products only when a contract benefit for the specific service exists. Medical policies only apply to Medicare products when a contract benefit exists and where there are no National or Local Medicare coverage decisions for the specific service. POLICY STATEMENT: Treatment: I. Based upon our criteria and assessment of peer-reviewed literature, the following treatment modalities have been medically proven to be effective and are considered medically appropriate in patients with known erectile dysfunction with symptoms lasting more than 6 months. Treatment may be initiated prior to 6 months in cases of an acute event such as, penile trauma or radical pelvic surgery (e.g., prostatectomy or cystectomy), or drug-induced erectile dysfunction caused by treatment of a co-morbid condition. The least invasive procedure should be the first line of treatment. If a member fails oral therapy, generally a durable medical equipment (DME) modality should be the next step in treatment. A. Oral Drug Therapy: Sildenafil citrate (Viagra), Vardenafil (Levitra), and Tadalafil (Cialis®) block the effect of an enzyme, Phosphodiesterase-5 (PDE5), causing an increase in penile blood flow necessary for an erection. -

International Brazilian Journal of Urology

ISSN 1677-5538 International Braz J Urol Official Journal of the Brazilian Society of Urology Volume 29, Number 4, July - August, 2003 XXX Brazilian Congress of Urology October 23-28, 2005 - Brasília - DF www.brazjurol.com.br Full Text Online Access Available International Braz J Urol EDITORS COMMENT The July August 2003 issue of the International Braz J Urol presents interesting contributions and the Editor will highlight some important papers. Doctors Holzbeierlein and colleagues, from University of Kansas Medical Center, Kansas City and Medical College of Wisconsin, Milwaukee, USA, authored on page 291 a through presentation on case selection and outcome of radical perineal prostatectomy in localized prostate cancer. It was emphasized that proper patient selection is critical to the success of the procedure and the minimization of complications. The authors concluded that radical perineal prostatectomy has stood the test of time, with only a few technical modifications since its original description more than 100 years ago. The procedure offers outcomes similar to radical retropubic prostatectomy, the standard approach for the treatment of localized prostate cancer. Its advantages include decreased pain, blood loss, and convalescence, the same arguments currently being made in favor of laparoscopic prostatectomy. Doctors Srougi and co-workers, from Federal University of São Paulo, Brazil, presented on page 336 a modification of the radical cystectomy technique with preservation of sexual function and urinary continence. The authors stated that the proposed maneuvers allow the performance of radical cystectomy with integral preservation of distal urethral sphincter and of cavernous neurovascular bundles, without jeopardizing the oncological principles. Doctor Mark S. -

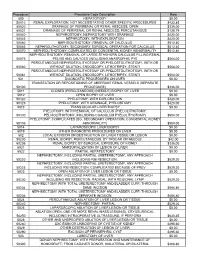

Procedure Procedure Code Description Rate 500

Procedure Procedure Code Description Rate 500 HEPATOTOMY $0.00 50010 RENAL EXPLORATION, NOT NECESSITATING OTHER SPECIFIC PROCEDURES $433.85 50020 DRAINAGE OF PERIRENAL OR RENAL ABSCESS; OPEN $336.00 50021 DRAINAGE OF PERIRENAL OR RENAL ABSCESS; PERCUTANIOUS $128.79 50040 NEPHROSTOMY, NEPHROTOMY WITH DRAINAGE $420.00 50045 NEPHROTOMY, WITH EXPLORATION $420.00 50060 NEPHROLITHOTOMY; REMOVAL OF CALCULUS $512.40 50065 NEPHROLITHOTOMY; SECONDARY SURGICAL OPERATION FOR CALCULUS $512.40 50070 NEPHROLITHOTOMY; COMPLICATED BY CONGENITAL KIDNEY ABNORMALITY $512.40 NEPHROLITHOTOMY; REMOVAL OF LARGE STAGHORN CALCULUS FILLING RENAL 50075 PELVIS AND CALYCES (INCLUDING ANATROPHIC PYE $504.00 PERCUTANEOUS NEPHROSTOLITHOTOMY OR PYELOSTOLITHOTOMY, WITH OR 50080 WITHOUT DILATION, ENDOSCOPY, LITHOTRIPSY, STENTI $504.00 PERCUTANEOUS NEPHROSTOLITHOTOMY OR PYELOSTOLITHOTOMY, WITH OR 50081 WITHOUT DILATION, ENDOSCOPY, LITHOTRIPSY, STENTI $504.00 501 DIAGNOSTIC PROCEDURES ON LIVER $0.00 TRANSECTION OR REPOSITIONING OF ABERRANT RENAL VESSELS (SEPARATE 50100 PROCEDURE) $336.00 5011 CLOSED (PERCUTANEOUS) (NEEDLE) BIOPSY OF LIVER $0.00 5012 OPEN BIOPSY OF LIVER $0.00 50120 PYELOTOMY; WITH EXPLORATION $420.00 50125 PYELOTOMY; WITH DRAINAGE, PYELOSTOMY $420.00 5013 TRANSJUGULAR LIVER BIOPSY $0.00 PYELOTOMY; WITH REMOVAL OF CALCULUS (PYELOLITHOTOMY, 50130 PELVIOLITHOTOMY, INCLUDING COAGULUM PYELOLITHOTOMY) $504.00 PYELOTOMY; COMPLICATED (EG, SECONDARY OPERATION, CONGENITAL KIDNEY 50135 ABNORMALITY) $504.00 5014 LAPAROSCOPIC LIVER BIOPSY $0.00 5019 OTHER DIAGNOSTIC PROCEDURES -

Male Reproductive Health

CHAPTER 12 Male Reproductive Health Male Infertility Erectile Dysfunction Peyronie’s Disease Vasectomy Undescended Testes 406 | Urologic Diseases In America Table 12-1. Codes used in the diagnosis and management of male reproductive health Erectile Dysfunction Males 18 years or older with one or more of the following: ICD-9 diagnosis codes 302.7 Psychosexual dysfunction 302.70 Psychosexual dysfunction, unspecified 302.71 Psychosexual dysfunction with inhibited sexual desire 302.72 Psychosexual dysfunction with inhibited sexual excitement 302.74 Psychosexual dysfunction with inhibited male orgasm 607.82 Vascular disorders of penis 607.84 Impotence of organic origin 607.89 Other specified disorders of penis 607.9 Unspecified disorder of penis ICD-9 procedure codes 64.94 Fitting of external prosthesis of penis 64.95 Insertion or replacement of non-inflatable penile prosthesis 64.96 Removal of internal prosthesis of penis 64.97 Insertion or replacement of inflatable penile prosthesis CPT procedure codes 37788 Penile revascularization, artery, with or without vein graft 37790 Penile venous occlusive procedure 54115 Removal foreign body from deep penile tissue (eg, plastic implant) 54230 Injection procedure for corpora cavernosography 54231 Dynamic cavernosometry, including intracavernosal injection of vasoactive drugs (eg, papaverine, phentolamine) 54235 Injection of corpora cavernosa with pharmacologic agent(s) (eg, papaverine, phentolamine) 54240 Penile plethysmography 54250 Nocturnal penile tumescence and/or rigidity test 54400 Insertion -

The Effects of Age, Ethnicity, Sexual Dysfunction, Urinary Incontinence, Masculinity, and Relationship with the Partner on the Q

Florida International University FIU Digital Commons FIU Electronic Theses and Dissertations University Graduate School 11-8-2013 The ffecE ts of Age, Ethnicity, Sexual Dysfunction, Urinary Incontinence, Masculinity, and Relationship with the Partner on the Quality of Life of Men with Prostate Cancer Suha Ballout Florida International University, [email protected] DOI: 10.25148/etd.FI13120415 Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.fiu.edu/etd Part of the Family Practice Nursing Commons, Gender and Sexuality Commons, Geriatric Nursing Commons, Male Urogenital Diseases Commons, and the Race and Ethnicity Commons Recommended Citation Ballout, Suha, "The Effects of Age, Ethnicity, Sexual Dysfunction, Urinary Incontinence, Masculinity, and Relationship with the Partner on the Quality of Life of Men with Prostate Cancer" (2013). FIU Electronic Theses and Dissertations. 978. https://digitalcommons.fiu.edu/etd/978 This work is brought to you for free and open access by the University Graduate School at FIU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in FIU Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of FIU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. FLORIDA INTERNATIONAL UNIVERSITY Miami, Florida THE EFFECTS OF AGE, ETHNICITY, SEXUAL DYSFUNCTION, URINARY INCONTINENCE, MASCULINITY, AND RELATIONSHIP WITH THE PARTNER ON THE QUALITY OF LIFE OF MEN WITH PROSTATE CANCER A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in NURSING by Suha Ballout 2013 To: Dean Ora Lea Strickland College of Nursing and Health Sciences This dissertation, written by Suha Ballout, and entitled The Effects of Age, Ethnicity, Sexual Dysfunction, Urinary Incontinence, Masculinity, and Relationship with the Partner on the Quality of Life of Men with Prostate Cancer, having been approved in respect to style and intellectual content, is referred to you for judgment. -

Abstracts 1..6

International Journal of Impotence Research (2000) 12, Suppl 5, S1±S12 ß 2000 Macmillan Publishers Ltd All rights reserved 0955-9930/00 $15.00 www.nature.com/ijir ORAL PRESENTATIONS 12 SEXUAL REHABILITATION: CLINICAL EXPERIENCE WITH WITHDRAWN SILDENAFIL CITRATE (VIAGRA TM) IN SPINAL CORD INJURED PATIENTS. ·- G Raviv, RJ Heruti, A Shaked, H Katz, A Ohry, J Ramon and I Madgar. Department of Urology, the Andrology Unit and the Neuro-Rehabilitation department, Sheba Medical Center, Tel-Hashomer, ISRAEL. Introduction & Objectives: Sexual dysfunction in spinal cord injured patients (SCIP) inflicts significant emotional and physical stress upon the patients. Recently Viagra. a potent inhibitor of cyclic guanosine monophosphate in the corpus cavemosum, was introduced as a new drug for conservative treatment of sexual dysfunction. The aim of this study was to assess the clinical efficacy of Viagra nl in SCIP. Subjects and Methods: 60 patients were included in the study. The patients underwent a complete evaluation process consisting of medical history, physical examination and blood tests. Rigiscan and EMG and SSEP of BCR were performed in patients with incomplete lesions and in those suspected to be of mixed origin. Each patient entering the stvdy completed the International fndex of Erectile Function questionnaire (IIEF). All patients were given 50mg as astarting dose that \vas increased to 1OOmg based on efficacy and tolerance except for quadriplegic and psychogenic erectile dysfunction patients in whom the starting dose was 25mg. Success was defined as improvement in the ability to have sexual intercourse. and the wish to continue the treatment. Results: The average age was 35.2::!::: 11.7 years (range I 9-58). -

Successful Penile Reimplantation and Systematic Review of World Literature 255

African Journal of Urology (2017) 23, 253–257 African Journal of Urology Official journal of the Pan African Urological Surgeon’s Association web page of the journal www.ees.elsevier.com/afju www.sciencedirect.com Genito-Urinary Trauma Case report Successful penile reimplantation and systematic review of world literature ∗ J.E. Mensah , L.D. Bray , E. Akpakli , M.Y. Kyei , M. Oyortey Department of Surgery and Urology, School of Medicine and Dentistry, College of Health Sciences, University of Ghana, P.O. Box 4236, Accra, Ghana Received 20 July 2016; received in revised form 17 January 2017; accepted 22 February 2017 Available online 30 August 2017 KEYWORDS Abstract Traumatic; Introduction: There is paucity of case reports that describe successful non-microscopic penile reimplan- Penile amputation; tation. We report a case of a self-inflicted penile amputation in an apparently normal patient with first Reimplantation; psychotic break. Psychiatric illness; Observation: To report on a case of successful macrosurgical penile reimplantation, discuss the etiologies, Penile transplantation surgical techniques and outcomes of world literature on penile reimplantation and an update of current trends in penile surgery. A 40 year-old male, father of 3 children and a proprietor of a nursery school with no prior pschiatric disorder was rushed to our trauma centre following a self-inflicted total penile amputation at its base with incomplete laceration of the scrotum due to command hallucination. He was immediately resuscitated and underwent a non-microscopic penile reimplantation and scrotal closure by an experienced urologist (JEM) by reattaching the dorsal vein, urethra, corporal, fascial and skin layers. A functional outcome with respect to voiding, penile erection and cosmesis was excellent.