The Transformation of Kongo Minkisi in African American Art

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A General Survey of Religious Concepts and Art of North, East, South, and West Africa

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 369 692 SO 023 792 AUTHOR Stewart, Rohn TITLE A General Survey of Religious Concepts and Art of North, East, South, and West Africa. PUB DATE Jun 92 NOTE llp.; Paper presented at the Annual Meeting of the National Art Education Association (Kansas City, KS, 1990). AVAILABLE FROMRohn Stewart, 3533 Pleasant Avenue South, Minneapolis, MN 55408 ($3). PUB TYPE Reports Descriptive (141) Speeches/Conference Papers (150) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC01 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Area Studies; *Art; *Art Education; *Cultural Background; Foreign Countries; Higher Education; Interdisciplinary Approach; Multicultural Education; *Religion; *Religious Cultural Groups IDENTIFIERS *Africa ABSTRACT This paper, a summary of a multi-carousel slide presentation, reviews literature on the cultures, religions, and art of African people. Before focusing on West Africa, highlights of the lifestyles, religions, and icons of non-maskmaking cultures of North, West and South African people are presented. Clarification of West African religious concepts of God, spirits, and magic and an examination of the forms and functions of ceremonial headgear (masks, helmets, and headpieces) and religious statues (ancestral figures, reliquaries, shrine figures, spirit statues, and fetishes) are made. An explanation of subject matter, styles, design principles, aesthetic concepts and criteria for criticism are presented in cultural context. Numerous examples illustrated similarities and differences in the world views of West African people and European Americans. The paper -

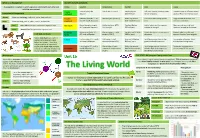

The Living World

1 The Living World MultipleChoiceQuestions (MCQs) 1 As we go from species to kingdom in a taxonomic hierarchy, the number of common characteristics (a)willdecrease (b)willincrease (c)remainsame (d) mayincreaseordecrease Ans. (a) Lower the taxa, more are the characteristic that the members within the taxon share. So, lowest taxon share the maximum number of morphological similarities, while its similarities decrease as we move towards the higher hierarchy, i.e., class, kingdom. Thus,restoftheoptionareincorrect. 2 Which of the following ‘suffixes’ used for units of classification in plants indicates a taxonomic category of ‘family’? (a) − Ales (b) − Onae (c) − Aceae (d) − Ae K ThinkingProcess Biological classification of organism is a process by which any living organism is classified into convenient categories based on some common observable characters. The categoriesareknownas taxons. Ans. (c) The name of a family, a taxon, in plants always end with suffixes aceae, e.g., Solanaceae, Cannaceae and Poaceae. Ales suffix is used for taxon ‘order’ while ae suffix is used for taxon ‘class’ and onae suffixesarenotusedatallinanyofthetaxons. 3 The term ‘systematics’ refers to (a)identificationandstudyoforgansystems (b)identificationandpreservationofplantsandanimals (c)diversityofkindsoforganismsandtheirrelationship (d) studyofhabitatsoforganismsandtheirclassification K ThinkingProcess The planet earth is full of variety of different forms of life. The number of species that are named and described are between 1.7-1.8 million. As we explore new areas, new organisms are continuously being identified, named and described on scientific basis of systematicslaiddownbytaxonomists. 1 2 (Class XI) Solutions Ans. (c) The word systematics is derived from Latin word ‘Systema’ which means systematic arrangement of organisms. Linnaeus used ‘Systema Naturae’ as a title of his publication. -

Art Power : Tactiques Artistiques Et Politiques De L’Identité En Californie (1966-1990) Emilie Blanc

Art Power : tactiques artistiques et politiques de l’identité en Californie (1966-1990) Emilie Blanc To cite this version: Emilie Blanc. Art Power : tactiques artistiques et politiques de l’identité en Californie (1966-1990). Art et histoire de l’art. Université Rennes 2, 2017. Français. NNT : 2017REN20040. tel-01677735 HAL Id: tel-01677735 https://tel.archives-ouvertes.fr/tel-01677735 Submitted on 8 Jan 2018 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. THESE / UNIVERSITE RENNES 2 présentée par sous le sceau de l’Université européenne de Bretagne Emilie Blanc pour obtenir le titre de Préparée au sein de l’unité : EA 1279 – Histoire et DOCTEUR DE L’UNIVERSITE RENNES 2 Mention : Histoire et critique des arts critique des arts Ecole doctorale Arts Lettres Langues Thèse soutenue le 15 novembre 2017 Art Power : tactiques devant le jury composé de : Richard CÁNDIDA SMITH artistiques et politiques Professeur, Université de Californie à Berkeley Gildas LE VOGUER de l’identité en Californie Professeur, Université Rennes 2 Caroline ROLLAND-DIAMOND (1966-1990) Professeure, Université Paris Nanterre / rapporteure Evelyne TOUSSAINT Professeure, Université Toulouse - Jean Jaurès / rapporteure Elvan ZABUNYAN Volume 1 Professeure, Université Rennes 2 / Directrice de thèse Giovanna ZAPPERI Professeure, Université François Rabelais - Tours Blanc, Emilie. -

Alison Saar Foison and Fallow

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE August 2010 Media Contact: Elizabeth East Telephone: 310-822-4955 Email: [email protected] Alison Saar Foison and Fallow 15 September through 30 October 2010 Opening reception for the artist: Wednesday 15 September, 6-8 p.m. Venice, CA –- L.A. Louver is pleased to announce an exhibition of new three-dimensional mixed media works on paper and sculpture by Alison Saar. In this new work Saar explores the cycle of birth, maturation, death and regeneration through the changing season and her own experience of aging. The two drawings Foison, 2010 and Fallow, 2010, which also give their titles to the exhibition, derive from Saar’s recent fascination with early anatomy illustration. As Saar has stated “The artists of the time seemed compelled to breathe life back into the cadavers, depicting them dancing with their entrails, their skin draped over their arm like a cloak, or fe- tuses blooming from their mother’s womb.” In these drawings, Saar has replaced the innards of the fi gures with incongruous elements, to create a small diorama: Foison, 2010 depicts ripe, fruitful cotton balls and their nemesis the cotton moth, in caterpillar, chrysalis and mature moth stage; while Fallow, 2010 portrays a fallow fawn fetus entwined in brambles. In creating these works Saar references and reexamines her early work Alison Saar that often featured fi gures with “cabinets’ in their chest containing relics Fallow, 2010 mixed media of their life. 55 1/2 x 29 x 1 in. (141 x 73.7 x 2.5 cm) My work has always dealt with dualities -- usually of the wild, feral side in battle with the civil self -----Alison Saar One of two sculptures in the exhibition, En Pointe, 2010 depicts a fi gure hanging by her feet and sprouting massive bronze antlers. -

Reglas De Congo: Palo Monte Mayombe) a Book by Lydia Cabrera an English Translation from the Spanish

THE KONGO RULE: THE PALO MONTE MAYOMBE WISDOM SOCIETY (REGLAS DE CONGO: PALO MONTE MAYOMBE) A BOOK BY LYDIA CABRERA AN ENGLISH TRANSLATION FROM THE SPANISH Donato Fhunsu A dissertation submitted to the faculty of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of English and Comparative Literature (Comparative Literature). Chapel Hill 2016 Approved by: Inger S. B. Brodey Todd Ramón Ochoa Marsha S. Collins Tanya L. Shields Madeline G. Levine © 2016 Donato Fhunsu ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ii ABSTRACT Donato Fhunsu: The Kongo Rule: The Palo Monte Mayombe Wisdom Society (Reglas de Congo: Palo Monte Mayombe) A Book by Lydia Cabrera An English Translation from the Spanish (Under the direction of Inger S. B. Brodey and Todd Ramón Ochoa) This dissertation is a critical analysis and annotated translation, from Spanish into English, of the book Reglas de Congo: Palo Monte Mayombe, by the Cuban anthropologist, artist, and writer Lydia Cabrera (1899-1991). Cabrera’s text is a hybrid ethnographic book of religion, slave narratives (oral history), and folklore (songs, poetry) that she devoted to a group of Afro-Cubans known as “los Congos de Cuba,” descendants of the Africans who were brought to the Caribbean island of Cuba during the trans-Atlantic Ocean African slave trade from the former Kongo Kingdom, which occupied the present-day southwestern part of Congo-Kinshasa, Congo-Brazzaville, Cabinda, and northern Angola. The Kongo Kingdom had formal contact with Christianity through the Kingdom of Portugal as early as the 1490s. -

C Ollections

The University of Wisconsin System - FEMINIST- OLLECTIONS CA QUARTERLYOF WOMEN'S STUDIES RESOURCES TABLE OF CONTENTS BOOKREVIEWS.................................. ................4 THE PERSPECTIVES OF FOUR NATIVE AMERICAN WOMEN WRITERS, by Chris Jendrisak. From theRiverls Edge, by Elizabeth Cook-Lynn; Mean Spirit, by Linda Hogan; Almanacof the Dead, by LeslieMarmon Si1ko;and Grandmothersof the Light: AMedicine Woman's Sourcebook, by Paula Gunn Allen. ACROBATS ON THE TIGHTROPE BETWEEN PHILOSOPHY AND FEMINISM: NO- MADIC FEMALE FEMINISTS AND/OR FEISTY FEMINISTS? by Sharon Scherwitz. Patterns of Dissonance: A Study of Women in Contemporary Philosophy, by Rosi Braidotti; and Feminist Ethics, ed. by Claudia Card. SOUTHERN WOMEN WRITERS AND THE LITERARY CANON, by Michele Alperin. Homeplaces: Stories of the South by Women Writers, ed. by Mary Ellis Gibson; Female Pastoral: Women WritersRe-Visioning theAmerican South,by Elizabeth JaneHamson; Southern Women Writers: The New Generation, ed. by Tonnette Bond Inge; and Friendship and Sympathy: Communities of Southern Women Writers, ed. by Rosemary M. Magee. ARCHIVES ......................................................12 FEMINIST VISIONS ............................................. .13 THE PRINCESS AND THE SQUAW: IMAGES OF AMERICAN INDIAN WOMEN IN CINEMA ROUGE, by Judith Logsdon THE INDEXING OF WOMEN'S STUDIES JOURNALS.. ..............17 By Judith Hudson RESEARCH EXCHANGE ..........................................20 FEMINIST PUBLISHING ..........................................20 A publishing handbook -

An African Basketry of Heterogeneous Variables Kongo-Kikongo-Kisankasa

ISSN 2394-9694 International Journal of Novel Research in Humanity and Social Sciences Vol. 8, Issue 2, pp: (2-31), Month: March - April 2021, Available at: www.noveltyjournals.com An African Basketry of Heterogeneous Variables Kongo-Kikongo-Kisankasa Rojukurthi Sudhakar Rao (M.Phil Degree Student-Researcher, Centre for African Studies, University of Mumbai, Maharashtra Rajya, India) e-mail:[email protected] Abstract: In terms of scientific systems approach to the knowledge of human origins, human organizations, human histories, human kingdoms, human languages, human populations and above all the human genes, unquestionable scientific evidence with human dignity flabbergasted the European strong world of slave-masters and colonialist- policy-rulers. This deduces that the early Europeans knew nothing scientific about the mankind beforehand unleashing their one-up-man-ship over Africa and the Africans except that they were the white skinned flocks and so, not the kith and kin of the Africans in black skin living in what they called the „Dark Continent‟! Of course, in later times, the same masters and rulers committed to not repeating their colonialist racial geo-political injustices. The whites were domineering and weaponized to the hilt on their own mentality, for their own interests and by their own logic opposing the geopolitically distant African blacks inhabiting the natural resources enriched frontiers. Those „twists and twitches‟ in time-line led to the black‟s slavery and white‟s slave-trade with meddling Christian Adventist Missionaries, colonialists, religious conversionists, Anglican Universities‟ Missions , inter- sexual-births, the associative asomi , the dissociative asomi and the non-asomi divisions within African natives in concomitance. -

The Living World Components & Interrelationships Management

What is an Ecosystem? Biome’s climate and plants An ecosystem is a system in which organisms interact with each other and Biome Location Temperature Rainfall Flora Fauna with their environment. Tropical Centred along the Hot all year (25-30°C) Very high (over Tall trees forming a canopy; wide Greatest range of different animal Ecosystem’s Components rainforest Equator. 200mm/year) variety of species. species. Most live in canopy layer Abiotic These are non-living, such as air, water, heat and rock. Tropical Between latitudes 5°- 30° Warm all year (20-30°C) Wet + dry season Grasslands with widely spaced Large hoofed herbivores and Biotic These are living, such as plants, insects, and animals. grasslands north & south of Equator. (500-1500mm/year) trees. carnivores dominate. Flora Plant life occurring in a particular region or time. Hot desert Found along the tropics Hot by day (over 30°C) Very low (below Lack of plants and few species; Many animals are small and of Cancer and Capricorn. Cold by night 300mm/year) adapted to drought. nocturnal: except for the camel. Fauna Animal life of any particular region or time. Temperate Between latitudes 40°- Warm summers + mild Variable rainfall (500- Mainly deciduous trees; a variety Animals adapt to colder and Food Web and Chains forest 60° north of Equator. winters (5-20°C) 1500m /year) of species. warmer climates. Some migrate. Simple food chains are useful in explaining the basic principles Tundra Far Latitudes of 65° north Cold winter + cool Low rainfall (below Small plants grow close to the Low number of species. -

Videostudio Playback

VideoStudio Playback Houston Conwill Maren Hassinger Fred Holland Ishmael Houston-Jones Ulysses Jenkins Senga Nengudi Howardena Pindell 10 06 16 Spring 2011 04 –“I am laying on the between the predeter- “No, Like This.” floor. My knees are up. mined codes of language Movements in My left arm is extended and their meaning to the side.” when actually used. Performance, –“Is it open?” By setting live human Video and the –“The palm of my left hand bodies to a technologically is open. Um, it’s not really reproduced voice, Babble Projected Image, open. It’s kind of cupped a addresses the mutable 1980–93 little bit, halfway between boundary between human open and shut.” and machine. While –“Like this?” mechanical manipulation Thomas J. Lax –“No, like this.” is commonly thought to –“Do we have to do this be synthetic and external now?” to original artistic work, –“Like this?” their performance demon- –“Okay.” strates the ways in which –“Okay.” technology determines something thought to This informal, circuitous, be as organic and natural instruction begins a as the human body. vignette in Babble: First Impressions of the White For its conceptual frame- Man (1983), a choreo- work, this exhibition graphic collaboration draws on Babble’s tension between artists Ishmael between spontaneous Houston-Jones and human creativity and Fred Holland. Although technology’s possibilities Houston-Jones is, as he and limitations. Bring- says, laying on the floor ing together work in film with his knees up and and video made primarily his left arm open, his between 1980 and 1986 voice is prerecorded and by seven artists who were removed from his onstage profoundly influenced by body. -

“Spiritist Mediumship As Historical Mediation: African-American Pasts

Journal of Religion in Africa 41 (2011) 330-365 brill.nl/jra Spiritist Mediumship as Historical Mediation: African-American Pasts, Black Ancestral Presence, and Afro-Cuban Religions Elizabeth Pérez, Ph.D. Dartmouth College, Department of Religion 305 !ornton Hall, Hanover, NH 03755, USA [email protected] Abstract !e scholarship on Afro-Atlantic religions has tended to downplay the importance of Kardecist Espiritismo. In this article I explore the performance of Spiritist rituals among Black North American practitioners of Afro-Cuban religions, and examine its vital role in the development of their religious subjectivity. Drawing on several years of ethnographic research in a Chicago-based Lucumí community, I argue that through Spiritist ceremonies, African-American participants engaged in memory work and other transformative modes of collective historiographical praxis. I contend that by inserting gospel songs, church hymns, and spirituals into the musical reper- toire of misas espirituales, my interlocutors introduced a new group of beings into an existing category of ethnically differentiated ‘spirit guides’. Whether embodied in ritual contexts or cul- tivated privately through household altars, these spirits not only personify the ancestral dead; I demonstrate that they also mediate between African-American historical experience and the contemporary practice of Yorùbá- and Kongo-inspired religions. Keywords African Diaspora, Black North American religion, historiography, Santería, Espiritismo, spirit possession Pirates of the Afro-Caribbean World Among practitioners of Afro-Cuban religions such as Palo Monte and Lucumí, popularly called Santería, Spiritist ceremonies are frequently celebrated. !is has been the case wherever these traditions’ distinct yet interrelated classes of spirits—including Kongo mpungus and Yorùbá orishas—have gained a foot- hold, particularly in global urban centers. -

African Concepts of Energy and Their Manifestations Through Art

AFRICAN CONCEPTS OF ENERGY AND THEIR MANIFESTATIONS THROUGH ART A thesis submitted to the College of the Arts of Kent State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts by Renée B. Waite August, 2016 Thesis written by Renée B. Waite B.A., Ohio University, 2012 M.A., Kent State University, 2016 Approved by ____________________________________________________ Fred Smith, Ph.D., Advisor ____________________________________________________ Michael Loderstedt, M.F.A., Interim Director, School of Art ____________________________________________________ John R. Crawford-Spinelli, D.Ed., Dean, College of the Arts TABLE OF CONTENTS LIST OF FIGURES………………………………………….. iv ACKNOWLEDGMENTS …………………………………… vi CHAPTERS I. Introduction ………………………………………………… 1 II. Terms and Art ……………………………………………... 4 III. Myths of Origin …………………………………………. 11 IV. Social Structure …………………………………………. 20 V. Divination Arts …………………………………………... 30 VI. Women as Vessels of Energy …………………………… 42 VII. Conclusion ……………………………………….…...... 56 VIII. Images ………………………………………………… 60 IX. Bibliography …………………………………………….. 84 X. Further Reading ………………………………………….. 86 iii LIST OF FIGURES Figure 1: Porogun Quarter, Ijebu-Ode, Nigeria, 1992, Photograph by John Pemberton III http://africa.si.edu/exhibits/cosmos/models.html. ……………………………………… 60 Figure 2: Yoruba Ifa Divination Tapper (Iroke Ifa) Nigeria; Ivory. 12in, Baltimore Museum of Art http://www.artbma.org/. ……………………………………………… 61 Figure 3.; Yoruba Opon Ifa (Divination Tray), Nigerian; carved wood 3/4 x 12 7/8 x 16 in. Smith College Museum of Art, http://www.smith.edu/artmuseum/. ………………….. 62 Figure 4. Ifa Divination Vessel; Female Caryatid (Agere Ifa); Ivory, wood or coconut shell inlay. Nigeria, Guinea Coast The Metropolitan Museum of Art, http://www.metmuseum.org. ……………………… 63 Figure 5. Beaded Crown of a Yoruba King. Nigerian; L.15 (crown), L.15 (fringe) in. -

Liberated Central Africans in Nineteenth-Century Guyana1

HARRIET TUBMAN SEMINAR York University January 24, 2000 Liberated Central Africans in Nineteenth-Century Guyana1 Monica Schuler Department of History Wayne State University Statistics of the nineteenth century slave trade and liberated African immigration (1841- 1865), while incomplete, show the replacement of a West African by a Central African majority in Guyana, a country comprising the three former Dutch colonies of Demerara, Essequibo and Berbice.2 The ethnic patterns of the Dutch slave trade, which supplied the majority of enslaved Africans until British occupation in 1796, indicate that 29 percent of the Africans on Dutch West India ships and 34 percent on free traders’ ships came from the Loango hinterland in West Central Africa. Of the remainder transported by the Dutch West India Company, 45 percent originated in the Republic of Benin-western Nigeria area known as the Slave Coast, another 21 percent in the Gold Coast interior, and the rest in the Bight of Biafra region and Senegal. The Windward Coast area of present-day Liberia and Côte d'Ivoire provided 49 percent of the free traders’ cargo.3 With British occupation in 1796, Guyana obtained an infusion of capital and over 35,000 additional people from Britain’s legal African or Caribbean slave trade and from the migration of self-employed slave mechanics and hucksters. Owing to increased African importations early in the nineteenth century, Kongo came to outnumber other African groups in Berbice and probably in Demerara and Essequibo as well. To date, the Berbice slave register for 1819 provides the sole available ethnic profile for the late slave era in Guyana.