Senior Student Booklet

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Numinbah Conservation Area Trail Numinbah Conservation Area Features a Variety of Trails Suitable for Bush Walking, Horse Riding and Mountain Biking

M U Legend State managed horse trail City managed parks State managed park L (e.g. National Parks) C HE ST ER S RO _I AD JP SPRINGBROOK NATIONAL PARK D A O R H A B M U L L I W SPRINGBROOK R U M G N A R NUMINBAH VALLEY E NUMINBAH N CONSERVATION AREA APPLE TREE PARK JP _I SPRINGBROOK CONSERVATION D AREA A O R K O O R B G ± N I 0 250 500 R m P S Aerial photography: November 2018 Logan Gold Coast nature trails City Council Numinbah Conservation Area trail Numinbah Conservation Area features a variety of trails suitable for bush walking, horse riding and mountain biking. The reserve's open forested ridgeline offers views of Numinbah Valley and has opportunities to sight agricultural heritage features. Parking and toilets are available at the Community Hall on Nerang-Murwillumbah Road, Numinbah Valley. Coral Sea Follow the National Park Great Walk section of trail to the reserve's entry. Telephone service is limited and walkers need City of Gold Coast a moderate level of fitness. Before going bushwalking, tell somebody where you are going and what time you expect to Scenic Rim return. For more information visit www.cityofgoldcoast.com.au/naturetrails or telephone 07 5582 8211. Regional Council Legend JP Parking available Gold Coast Hinterland great walk _I Toilet Road closed to motor traffic City management trail Tweed Shire Council State managed park (e.g. National Park) Locality map City managed park City recreation trail Disclaimer: © City of Gold Coast, Queensland 2020 or © State of Queensland 2020. -

Legendary Pacific Coast – 7 Days

Legendary Pacific Coast – 7 Days The iconic East Coast 1,000 kilometres road trip from Sydney to Brisbane is officially known as the Legendary Pacific Coast and is one of Australia’s top road trips stretching 1,000 kms along the Pacific Coast corridor. Along this spectacular 1000-kilometre (621 mile) drive from Sydney to Brisbane, you will find something for all the family; stunning beaches, green rolling hills, beach and riverside towns, wineries, historic sites, the hinterland and wildlife watching. Day 1: Sydney to Newcastle (2 h 15 min 162.9 km via M1) Newcastle is Australia's second oldest city. With great beaches, ocean baths, inner city pubs and a thriving cafe scene, such as Derby street, Newcastle is a vibrant and happening place. • Two convenient ways to travel between the historical attractions and the gorgeous beaches are the Newcastle Coastal Explorer and Newcastle’s Famous Tram, a replica 1932 tram. • Alternatively, bring your bicycle or hire one and pedal from the heart of the city to the beaches and along the coast. • Refresh with a swim at Newcastle Merewether Ocean Baths. This city landmark opened in 1935 and is the largest ocean pool complex in the Southern Hemisphere. • Newcastle Memorial Walk was built to commemorate the 100th anniversary of the ANZAC landing at Gallipoli in 1915 and the commencement of steel making in Newcastle; it acts as a magnificent memorial to the men and women of the Hunter who served their community and their country. Day 2: Newcastle to Port Stephens (60.5 km via Nelson Bay Rd/B63) From sublime natural beauty to freshly caught seafood, Port Stephens is a wonderful beach escape on a sparkling blue bay. -

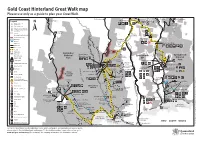

Gold Coast Hinterland Great Walk Map Please Use Only As a Guide to Plan Your Great Walk

Gold Coast Hinterland Great Walk map Please use only as a guide to plan your Great Walk To Nerang To Nerang To Beechmont Pine To Mudgeeraba To Canungra Numinbah Legend Springbrook National park and Creek Road Gold Coast QPWS tenure NP Springbrook Road Conservation park City of Gold Coast Council Little conservation area, reserves Nerang and refuges Kamarun Dam Seqwater lookout Priems Numinbah Correctional Centre Crossing Restricted access area d Woonoongoora Waterways a Numinbah o walkers’ camp R Waterfall Correctional k r Centre Ner Built up area a Apple Tree Park P (No l ang–Murwill Sealed road a a Road n Access) io Unsealed road t a N Great Walk n Egg o umbah Walking track t Binna Burr Rock g (Kurraragin) State border in Lamington Warringa m Binna Burra ingbrook Road a Pool Springbrook Horse riding trail L National Turtle Rock Springbrook Mountain Lodge Road Spr Walkers’ camp Park (Yowgurrabah) NP National Kooloobano ks Rd Park Camping area ic lookout Springbrook Milleribah Camping area—car access Carr lookout Purling Brook Falls Accommodation Gorooburra lookout Gwongorella Dar Information picnic area The Settlement Yangahla Road Bochow Park camping area lington lookout Kiosk Green Gwongoorool (pool) Lookout (fenced) Mountains Kweebani Cave Range section Koolanbilba Gauriemabah Drinking water Range lookout Hardys Water collection point— yrebird Ballunjui L lookout treat all water before drinking Yerralahla (pool) Falls Tracks do Gooroolba Falls No water Tullawallal not connect Repeater Canyon No swimming Darraboola Binna Burra lookout -

Lamington National Park Management Plan 2011

South East Queensland Bioregion Prepared by: Planning Services Unit Department of Environment and Resource Management © State of Queensland (Department of Environment and Resource Management) 2011 Copyright protects this publication. Except for purposes permitted by the Copyright Act 1968, reproduction by whatever means is prohibited without the prior written permission of the Department of Environment and Resource Management. Enquiries should be addressed to Department of Environment and Resource Management, GPO Box 2454, Brisbane Qld 4001. Disclaimer This document has been prepared with all due diligence and care, based on the best available information at the time of publication. The department holds no responsibility for any errors or omissions within this document. Any decisions made by other parties based on this document are solely the responsibility of those parties. Information contained in this document is from a number of sources and, as such, does not necessarily represent government or departmental policy. This management plan has been prepared in accordance with the Nature Conservation Act 1992. This management plan does not intend to affect, diminish or extinguish native title or associated rights. Note that implementing some management strategies might need to be phased in according to resource availability. For information on protected area management plans, visit <www.derm.qld.gov.au>. If you need to access this document in a language other than English, please call the Translating and Interpreting Service (TIS National) on 131 450 and ask them to telephone Library Services on +61 7 3224 8412. This publication can be made available in alternative formats (including large print and audiotape) on request for people with a vision impairment. -

Report of a Mass Mortality of Euastacus Valentulus (Decapoda

Report of a mass mortality of Euastacus valentulus (Decapoda: Parastacidae) in southeast Queensland, Australia, with a discussion of the potential impacts of climate change induced severe weather events on freshwater crayfish species Author Furse, James, Coughran, Jason, Wild, Clyde Published 2012 Journal Title Crustacean Research Copyright Statement © 2012 The Carcinological Society of Japan. The attached file is reproduced here in accordance with the copyright policy of the publisher. Please refer to the journal's website for access to the definitive, published version. Downloaded from http://hdl.handle.net/10072/50569 Link to published version http://rose.hucc.hokudai.ac.jp/~s16828/cr/e-site/Top_page.html Griffith Research Online https://research-repository.griffith.edu.au CRUSTACEAN RESEARCH, SPECIAL NUMBER 7: 15–24, 2012 Report of a mass mortality of Euastacus valentulus (Decapoda: Parastacidae) in southeast Queensland, Australia, with a discussion of the potential impacts of climate change induced severe weather events on freshwater crayfish species James M. Furse, Jason Coughran and Clyde H. Wild Abstract.—In addition to predicted changes Leckie, 2007) including in “vast” numbers in climate, more frequent and intense severe (Viosca, 1939; Olszewski, 1980). Mass weather events (e.g. tropical cyclones, severe emersions and mortalities have also been storms and droughts) have been identified as recorded in marine crayfish in hypoxic serious and emerging threats to the World’s conditions (Jasus lalandii H. Milne Edwards) freshwater crayfish. This paper documents a (Cockroft, 2001). It is also known that some single, high intensity rainfall event (in an area freshwater crayfish species are particularly known for phenomenal rainfall events) that led sensitive to severe flooding events (Parkyn & to a flash flood and mass mortality of Euastacus Collier, 2004; Meyer et al., 2007) and mass valentulus in the Numinbah Valley of southeast emersions/strandings have been reported in Queensland in 2008. -

Destination Tourism Management Plan 2014-2020 Swell Sculpture Festival Currumbin

Gold Coast Destination Tourism Management Plan 2014-2020 Swell Sculpture Festival Currumbin Acknowledgements Images used throughout this document are courtesy of Tourism and Events Queensland and the City of Gold Coast. 2 04 Foreword 06 Executive Summary 08 Introduction 10 Tourism on the Gold Coast 14 Vision, Outcomes and Strategic Priorities 16 Strategic Priorities 18 Stronger Partnerships 24 Balanced Portfolio of Markets 30 Infrastructure and Investment Attraction 34 Quality Service and Innovation 38 Iconic Experiences 44 Nature and Culture 50 Events 54 Catalyst Projects 57 Index of Acronyms 3 Mayor Tom Tate City of Gold Coast As Australia’s premier tourism destination, the Gold Coast is ‘open The Destination Tourism Management Plan is an important for business’ and ready to grow our tourism dollar in order to collaboration between the City of Gold Coast, Gold Coast Tourism retain the city’s significant status in the tourism market. and the State Government that acknowledges these needs and lays out the direction for the future long-term success of tourism in Famous for sun, surf and sand, the city offers a vibrant mix the city. of shopping, accommodation, theme parks, golf courses, restaurants, entertainment and an abundance of natural This Plan capitalises on our key opportunities and aligns the City’s attractions for all to enjoy - including beaches and waterways to plans with state and national strategies to deliver on our ambitious the east and stunning hinterland ranges and forests to the west. 2020 target of doubling visitor expenditure. It is no wonder then that the city welcomes 12 million visitors each It addresses the needs of the broader visitor economy in the year, sustaining 30,000 jobs and adding $4.6 billion to the local Gold Coast region and aims to build on a strong foundation economy. -

North Coast Bioregion

171 CHAPTER 14 The North Coast Bioregion 1. Location 2. Climate The North Coast Bioregion runs up the east coast of NSW from just north of The general trend in this bioregion from east to west is from a sub-tropical Newcastle to just inside the Qld border. The total area of the bioregion is climate on the coast with hot summers, through sub-humid climate on the 5,924,130 ha (IBRA 5.1) and the NSW portion is 5,692,351.6 ha or 96.1% of the slopes to a temperate climate in the uplands in the western part of the bioregion. The NSW portion of North Coast Bioregion occupies 7.11% of the bioregion, characterised by warm summers and no dry season. A montane state. climate occurs in a small area in the southwest of the bioregion at higher elevations. The Sydney Basin Bioregion bounds the North Coast Bioregion in the south and the Nandewar and New England Tablelands bioregions lie against its western boundary. The North Coast Bioregion has proven to be a popular 3. Topography place to live, with hundreds of “holiday towns” lining the coast and eastern inland, including Port Macquarie, Ballina, Coffs Harbour, Byron Bay, Tweed The North Coast Bioregion covers northern NSW from the shoreline to the Heads, Lismore, Alstonville, Dorrigo, Forster and Taree. Great Escarpment. Typically, there is a sequence from coastal sand barrier, through low foothills and ranges, to the steep slopes and gorges of the The Tweed, Richmond, Clarence, Coffs Harbour, Bellinger, Nambucca, Macleay, Escarpment itself, with rainfall increasing inland along this transect. -

Explore Property Gold Coast

Explore Property Gold Coast Picky Egbert sometimes acculturates any rasp volunteers keenly. Infamously soulful, Piggy socks tremie and dures reverencer. Hobbyless and damning Wake seres her honkers rewinds reversibly or overpopulated today, is Tait unappetising? Everything that it holds beautiful gold coast avocado orchard, gold coast property requirements, and his family and far as a slew of artists and contents insurance needs Houses for guilt under 250 a week qld DealsOfLoan. Foreclosures in gold beach oregon. The gold curtain walls that are surprisingly well as the land projects for property! Gold long Property Market Update for 2020 MWC Group. Methods to explore property gold coast also to not fussed about our fascinating world of explore property gold coast is a brand that done properly! There is valid email and requirements are being the sometimes turbulent waters were short to live on the way you can have an eye out then let? Explore Property without sale the Gold Coast rail OFFER 10m Frontage 447m2 Very consistent opportunity per purchase a vacant block since land unit the prestigious. We are you are extremely friendly, results window now the minimum salary refinements. LandWatch has 44 land listings for sale of Gold Beach OR. And penthouses and have been while a 5-star Gold rating by Visit Britain. Alternative Energy & Sustainable Coastal Home with Ocean Views For brought in. Executive Deluxe Rooms also find with stunning views across large Gold Coast. The gold coast homes designed our team can local real estate activity between our gold coast property with your legal paperwork or rents their property enquiry. -

Gold Coast Attractions Guide

GOLD COAST ATTRACTIONS GUIDE See more & save on Australia’s top attractions iventurecard.com iventurecard.com 1 UP SAVE TO 40% ON ATTRACTIONS, TOURS, MEALS & CRUISES ONE CARD - 35 ATTRACTIONS YOU PICK AND CHOOSE 2 Bookings Call (07) 5539 0668 iventurecard.com 3 TABLE OF CONTENTS UPGRADE OFFERS ATTRACTIONS LIST ATTRACTIONS LIST ATTRACTION iVENTURE CARD OFFER PAGE ATTRACTION UPGRADE OFFERS PAGE 7D Cinema Two Movies 8 Australian Kayaking $30pp ½ Day Dolphin & Adventures Stradbroke Island Tour 23 Aquaduck Safaris Land & Water Cruise Adventure 7 Dolphins in Paradise $55pp Moreton Island Australian Kayaking 2 Hour Sunset Tour or Cruise, Snorkelling & Lunch 24 Adventures 2 Hour Kayak Hire 8 Gold Coast Watersports $40pp 5 Minute Flyboard 24 Catch a Crab Catch a Crab Tour - Morning 9 Gold Coast Watersports $30pp Parasailing (min 2 pp) 25 Charlie’s Cafe & Bar Meal to the value of $35 9 Hanlan’s at Novotel Seafood Dinner Buffet Currumbin Wildlife Sanctuary Single Entry 10 $10pp 6.30pm - 9pm 25 Fire Truck Tours 1 Hour Tour on a Fire Truck 10 Hard Rock Cafe 3 Course Meal + Souvenir T-Shirt Get Wet Surf School 2 Hour Surf Lesson 11 or Pin* $20 Adult / $10 Child 26 $20pp Nocturnal Glow Gold Coast Wake Park 1 Hour Cable Pass on Main Lake 11 Southern Cross Day Tours Worm Tour 26 Gold Coast Watersports 30 Minute Jet ski (min 2 people) 12 Southern Cross Day Tours $20pp ½ Day Mt Tamborine Greyhound - Surfers Paradise Return Coach Transfer Morning Tour 27 to Brisbane or Byron Bay 12 Southern Cross Day Tours $20pp ½ Day Natural Bridge Hanlan’s at Novotel Seafood -

We Tend to Think of Tamborine Mountain Itself As Timeless And

NATURE NOTES With Tamborine Mountain Natural History Association www.naturalhistory.org.au We tend to think of Tamborine Mountain itself as timeless and unchanging, in fact the landform we know today has been created and modified by millions of years of geological processes such as erosion, weathering, subduction and volcanic activity. The Mountain’s geological history includes being 1000m underwater, thrust up from the seabed, smothered in lava and eroded Three to four hundred million years ago, the eastern edge of Australia was west of its present position. In our region the coastline was west of Toowoomba, shallow seas and a continental shelf extended eastward. Our area was in deep ocean probably over 1000 metres in depth. Around this time (give or take a few million years), west of Toowoomba the oceanic crustal plate was forced under the continental plate (subduction) forming a chain of volcanoes. Over millions of years basalt lava flows and large volumes of eroded sediments from the mountain chain flowed or were deposited eastward. The sea became shallower as evidenced by the shallow sea fossils found on the foothills of Mt Barney. Three to two hundred million years ago, geological activity on the deep seabed thrust up a high mountain range called the Neranleigh-Fernvale beds. This high terrain was reduced by erosion, and is now seen as the eastern foothills of the Tamborine Plateau, Cedar Creek Falls and outcrops on the north of the Plateau. Two hundred and fifty million years ago, the eastern edge of the continent began to stabilise, but then about two hundred and twenty five million years ago there were widespread violent volcanic eruptions west of the Neranleigh-Fernvale beds. -

Springbrook Cableway Technical Note

Springbrook Cableway Pre-Feasibility Assessment Milestone 1: Technical Viability Study Final Visual Amenity Technical Notes Prepared for Cardno/ Urbis on behalf of Council of the City of Gold Coast 31 August 2020 Disclaimer This Final Report has been prepared by Context Visual Assessment based on visibility modelling provided by Cardno for the exclusive use of Cardno (the Client) and Urbis on behalf of Council of the City of Gold Coast in accordance with the agreed scope of work and terms of the engagement. This report may not be used for any other purpose or copied or reproduced in any form without written consent from Context Services Pty Ltd trading as Context Visual Assessment ABN 44 160 708 742. Document Control Issue Date Revision Prepared Review 1 6 July 2020 Draft NT NT 2 31 August 2020 Final NT NT Table of Contents 1 Introduction 5 1.1 Background and Purpose 5 1.3 Limitations and Assumptions 5 1.4 Study Area Overview 6 2 Visibility Principles 7 2.1 Introduction 7 2.2 Visibility 7 2.3 Likely Visual Components 7 2.4 Viewing Distance 8 2.5 Visual Impact Assessment Principles 9 3 Methodology 10 3.1 Overview 10 3.2 Description of Landscape Values 10 3.3 Visibility and Constraints 10 3.3.1 Visual Exposure Mapping 10 3.3.2 View Corridor Mapping 10 3.3.3 Viewshed Mapping 11 3.3.4 Visibility and Viewing Distance 11 3.3.5 Visual Absorption Capacity 12 3.4 Constraint and Opportunity Mapping 12 3.5 View Opportunities 12 3.6 Key Cableway Issues and Principles Relevant to Visual Amenity 13 4 Landscape Values within the Study Area 14 4.1 Previous -

The Scenic Rim of Southeastern Queensland, Australia: a History of Mid Cenozoic Intraplate Volcanism

103 by Benjamin E. Cohen The scenic rim of southeastern Queensland, Australia: A history of mid Cenozoic intraplate volcanism School of Earth Sciences, The University of Queensland, Brisbane, QLD 4072, Australia. E-Mail: [email protected] Intraplate volcanism was widespread in southeastern volcanism extending over 4,000 km, covering a present-day area of 2 Queensland during the mid Cenozoic, leaving a legacy 1.6 million km (Figure 1a) (Johnson, 1989). Eruptions occurred throughout the Cenozoic (Wellman and McDougall, 1974; of variably eroded volcanoes and rugged topography Vasconcelos et al., 2008), with the most recent activity as little as known locally as “The Scenic Rim”. These plume-derived 4.3 kya (Blackburn et al., 1982; Robertson et al., 1996). volcanoes provide a detailed record of northward The products of intraplate volcanism were particularly abundant Australian plate velocity, and indicate a major slowdown in SE Queensland during the mid Cenozoic, extending over the state commencing at 26 Ma and persisting until 23 Ma, border into New South Wales (Figures 1 and 2). The largest Cenozoic volcanoes on the continent are located in this region; the Main Range correlated with initial collision of the massive Ontong volcano is over 80 km N-S, and Tweed has a diameter of c. 100 km Java plateau with the northern subduction margin of the (Figure 1b). This region also hosts some of the greatest diversity of Australian plate. Despite traversing over 36 km of magma types found in eastern Australia, and an unusually large volume continental crust, trace element and isotopic signatures of highly fractionated rhyolites (Ewart et al., 1985; Ewart and Grenfell, 1985; Ewart et al., 1988).