TF Magazine March 2007

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Tara/Skryne Valley and the M3 Motorway; Development Vs. Heritage

L . o . 4 .0 «? ■ U i H NUI MAYNOOTH Qll*c«il n> h£jf**nn Ml Nuad The Tara/Skryne Valley and the M3 Motorway; Development vs. Heritage. Edel Reynolds 2005 Supervisor: Dr. Ronan Foley Head of Department: Professor James Walsh Thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the M.A. (Geographical Analysis), Department of Geography, National University of Ireland, Maynooth. Abstract This thesis is about the conflict concerning the building of the MB motorway in an archaeologically sensitive area close to the Hill of Tara in Co. Meath. The main aim of this thesis was to examine the conflict between development and heritage in relation to the Tara/Skryne Valley; therefore the focus has been to investigate the planning process. It has been found that both the planning process and the Environmental Impact Assessment system in Ireland is inadequate. Another aspect of the conflict that was explored was the issue of insiders and outsiders. Through the examination of both quantitative and qualitative data, the conclusion has been reached that the majority of insiders, people from the Tara area, do in fact want the M3 to be built. This is contrary to the idea that was portrayed by the media that most people were opposed to the construction of the motorway. Acknowledgements Firstly, I would like to thank my supervisor, Ronan Foley, for all of his help and guidance over the last few months. Thanks to my parents, Helen and Liam and sisters, Anne and Nora for all of their encouragement over the last few months and particularly the last few days! I would especially like to thank my mother for driving me to Cavan on her precious day off, and for calming me down when I got stressed! Thanks to Yvonne for giving me the grand tour of Cavan, and for helping me carry out surveys there. -

DUBLIN 15 25 Woodview Park, Auburn Avenue, Castleknock

DUBLIN 15 25 Woodview Park, Auburn Avenue, Castleknock 01-853 6016 25 Woodview Park represents an excellent opportunity to acquire a well presented three bed semi-detached house in the heart of Castleknock Village off Auburn Avenue. Features A leafy entrance with an expansive zoned green area and mature trees leads to this • Located in the heart of Castleknock Village off Auburn Avenue charming small residential enclave that offers a tranquil cul-de-sac setting. Woodview • Excellent transport links both public and private Park’s location facilitates easily accesses the M50 and N3 road network and is in close proximity to a number of excellent local schools such as the Educate Together and St • Two storey semi-detached property built c.1986 Brigid’s National Schools as well as Castleknock College and Mount Sackville secondary • Woodgrain PVC double glazed windows schools. Cobble lock drive provides ample off-street parking for two-three cars and pedestrian access provides access to a west facing rear garden that is private and not • Gas fired central heating overlooked. • West facing rear garden with domestic block shed 25 Woodview Park enjoys a beautiful view from the living room towards the front • Contemporary kitchen of the estate and the rear garden is affored great privacy and has a south and west facing aspect enjoying sun from midday to sundown. The light filled accommodation • Fitted wardrobes to three bedrooms extends to 90sqm and comprises an entrance porch, entrance hall, living room, open • Hardwood floor throughout ground floor accommodation plan kitchen/dining room, two double bedrooms, a single bedroom and a bathroom. -

Dunshaughlin, Co

Professional All enquiries to sole agents UNSHAUGHLIN Team BUSINESS PARK MASON OWEN & LYONS D Developer 01 66 11 333 Jackie Greene Construction Limited Dunshaughlin, Co. Meath. EOIN CONWAY / JAMES HARDY 134 / 135 Lr. Baggot Street, Dublin 2. Ireland. Architects / Planning Advisor Tel: 01 6611333. Fax: 01 6611312. McCrossan O’Rourke Email: [email protected] Engineers Pat O’Gorman & Associates Solicitor George D. Fottrell and Sons Selling / Letting Agents Mason Owen & Lyons UNSHAUGHLIN D BUSINESS PARK artists impression an outstanding opportunity to not to scale acquire warehouse / office premises in a strategic location Messrs. Mason Owen & Lyons for themselves and for the vendors or lessors of this property whose Agents they are, give notice that 1. The particulars are set out as a general outline for the guidance of the intending purchasers or lessors and do not constitute, nor constitute part of an offer or contract, 2. All descriptions, dimensions, references to condition and necessary permissions for use and occupation, and other details are given in good faith and are believed to be correct, but intending purchasers or tenants should not rely on them as statements or representations of fact but must satisfy themselves by inspection or otherwise as to the correctness of each of them, 3. No person in the employment of Mason Owen & Lyons has any authority to make or give any representation or warranty in relation to this property, 4. Prices are quoted exclusive of VAT (unless otherwise stated) and all negotiations are conducted on the basis that the purchaser/lessee shall be liable for any VAT arising on the transaction. -

Overview of Research Programmes Operations

CEDR Transnational Road Research Programme Call 2012: Recycling: Road construction in a post-fossil fuel society funded by Denmark, Finland, Germany, Ireland, Netherlands and Norway EARN Report of laboratory and site testing for site trials Deliverable Nr. 8 December 2014 TRL Limited, UK University of Kassel University College Dublin Technische Universiteit Delft Lagan Asphalt Shell Bitumen, UK / Germany Shell CEDR Call 2012: Recycling: Road construction in a post-fossil fuel society EARN Effects on Availability of Road Network Deliverable Nr. 8 – Report of laboratory and site testing for site trials Due date of deliverable: 31.12.2014 Actual submission date: 04.12.2014 Start date of project: 01.01.2013 End date of project: 31.12.2014 Contributors to this deliverable: Amir Tabaković, University College Dublin Ciaran McNally, University College Dublin Amanda Gibney, University College Dublin Sean Cassidy, Lagan Asphalt Reza Shahmohammadi, Lagan Asphalt Stuart King, Lagan Asphalt Kevin Gilbert, Shell Bitumen (i) CEDR Call 2012: Recycling: Road construction in a post-fossil fuel society Table of contents 1 Introduction .................................................................................................................... 1 2 Full-scale testing ............................................................................................................ 1 2.1 Reason for site trial ............................................................................................... 1 2.2 Mixture design ...................................................................................................... -

Discover Ireland's Rich Heritage!

Free Guide Discover Ireland’s rich heritage! FOR MORE INFORMATION GO TO WWW.DISCOVERIRELAND.IE/BOYNEVALLEY 1 To Belfast (120km from Drogheda) Discover Ireland’s Ardee rich heritage! N2 M1 Oldcastle 6 12 14 13 Slane 7 4 KELLS 8 M3 Brú na Bóinne 15 Newgrange NAVAN Athboy N2 9 11 10 TRIM M3 2 FOR MORE INFORMATION GO TO WWW.DISCOVERIRELAND.IE/BOYNEVALLEY KEY 01 Millmount Museum Royal Site 02 St Peter’s Church, Drogheda To Belfast (120km from Drogheda) Monastery 03 Beaulieu House Megalithic Tomb 04 Battle of the Boyne Church 05 Mellifont Abbey Battle Site 06 Monasterboice Castle Dunleer Slane Castle Tower 07 Period House 08 Brú na Bóinne (Newgrange) M1 09 Hill of Tara 10 Trim Castle 6 11 Trim Heritage Town 3 12 Kells Heritage Town Round Tower 5 2 DROGHEDA & High Crosses 16 13 Loughcrew Gardens 4 1 14 Loughcrew Cairns 15 Navan County Town Brú na Bóinne 16 Drogheda Walled Town Newgrange M1 Belfast N2 M1 The Boyne Area Dublin To Dublin (50km from Drogheda) 2 FOR MORE INFORMATION GO TO WWW.DISCOVERIRELAND.IE/BOYNEVALLEY Discover Ireland’s rich heritage! Map No. Page No. Introduction 04 Archaeological & Historical Timeline 06 01 Millmount Museum & Martello Tower 08 02 St. Peter’s Church (Shrine of St. Oliver Plunkett) 10 03 Beaulieu House 12 04 Battle of the Boyne Site 14 05 Old Mellifont Abbey 16 06 Monasterboice Round Tower & High Crosses 18 07 Slane Castle 22 08 Brú na Bóinne (Newgrange & Knowth) 24 09 Hill of Tara 26 10 Trim Castle 28 11 Trim (Heritage Town) 30 12 Kells Round Tower & High Crosses 32 13 14 Loughcrew Cairns & Garden 34 15 Navan (County Town) 36 16 Drogheda (Walled Town) 38 Myths & Legends 40 Suggested Itinerary 1,2 & 3 46 Your Road map 50 Every care has been taken to ensure accuracy in the completion of this brochure. -

We Oil Irawm He Power to Pment Kiidc AIDS Helpl1ne 0800 012 322

KWAZULU-NATAL PROVINCE KWAZULU-NATAL PROVINSIE ISIFUNDAZWE SAKWAZULU-NATALI Provincial Gazette • Provinsiale Koerant • Igazethi Yesifundazwe (Registered at the post office as a newspaper) • (As ’n nuusblad by die poskantoor geregistreer) (Irejistiwee njengephephandaba eposihhovisi) PIETERMARITZBURG Vol. 10 21 JULY 2016 No. 1704 21 JULIE 2016 21 KUNTULIKAZI 2016 PART 1 OF 2 We oil Irawm he power to pment kiIDc AIDS HElPl1NE 0800 012 322 DEPARTMENT OF HEALTH Prevention is the cure ISSN 1994-4558 N.B. The Government Printing Works will 01704 not be held responsible for the quality of “Hard Copies” or “Electronic Files” submitted for publication purposes 9 771994 455008 2 No. 1704 PROVINCIAL GAZETTE, 21 JULY 2016 This gazette is also available free online at www.gpwonline.co.za PROVINSIALE KOERANT, 21 JULIE 2016 No. 1704 3 IMPORTANT NOTICE: THE GOVERNMENT PRINTING WORKS WILL NOT BE HELD RESPONSIBLE FOR ANY ERRORS THAT MIGHT OCCUR DUE TO THE SUBMISSION OF INCOMPLETE / INCORRECT / ILLEGIBLE COPY. NO FUTURE QUERIES WILL BE HANDLED IN CONNECTION WITH THE ABOVE. CONTENTS Gazette Page No. No. GENERAL NOTICES • ALGEMENE KENNISGEWINGS 26 Land Reform (Labour Tenants) Act (3/1996): Application in terms of Land Reform........................................... 1704 11 27 Labour Tenant Act, 1996: Oakbrook/Sub 126 of Spring Grove No. 2169 .......................................................... 1704 12 28 Land Reform (Labour Tenants) Act (3/1996): Excellosior Farm ......................................................................... 1704 13 29 Labour -

Noise and Vibration

North-South 400 kV Interconnection Development Environmental Impact Statement Volume 3D 9 AIR - NOISE AND VIBRATION 9.1 INTRODUCTION 1 This chapter evaluates the noise and vibration impacts arising from the proposed 400 kV overhead line (OHL) and associated development including the extension of Woodland Substation as set out in Chapter 6, Volume 3B of the Environmental Impact Statement (EIS). That chapter describes the full nature and extent of the proposed development, including elements of the OHL design and the towers. It provides a factual description, on a section by section basis, of the entire line route, including that portion within the Meath Study Area (MSA). The proposed line route is described in that chapter using townlands and tower numbers as a reference. The principal construction works proposed as part of the proposed development are set out in Chapter 7, Volume 3B of the EIS. 2 The information contained within this chapter is concerned with noise and vibration in the MSA as defined in Chapter 5, Volume 3B of the EIS. This evaluation deals with ‗audible‘ noise and vibration. 3 This evaluation considers an area in excess of 100m either side of the proposed alignment. The evaluation focuses on the construction, operation and decommissioning aspects of the proposed development. 4 This evaluation was prepared in accordance with the Environmental Protection Agency‘s (EPA) Guidelines on the information to be contained in Environmental Impact Statements (March 2002) and Advice Notes on Current Practice in the preparation of EIS (September 2003). 5 This chapter should be read in conjunction with Chapter 7, Volume 3B of the EIS and Chapter 13 in this volume of the EIS. -

Dissertation Title: the Pollution Potential of Road Salt on Freshwater Environments in Ireland Author: David Kelly Bsc. Academic

Dissertation Title: The Pollution Potential of Road Salt on Freshwater Environments in Ireland Author: David Kelly BSc. Academic Year: 2013/2014 Supervisor: Dr. Frances Lucy (I.T Sligo) Submitted: July 2014 This dissertation is submitted as part fulfilment of the MSc. in Environmental Protection, Institute of Technology, Sligo Plagiarism Declaration I hereby declare that this dissertation is all my own work and contains no plagiarism. Any text, diagrams or other material copied from other sources (including, but not limited to, books, journals and the internet) have been clearly acknowledged and referenced as such in the text. I also declare that the data collected for this dissertation has not been submitted to any other Institute or University for the award of any other third level qualification. Signed: Date: 7 th July 2014 Abstract Road salt or rock salt as it is sometimes known, is a commonly used de-icing material and is used throughout Ireland by local authorities (i.e. county councils), private road operators and members of the public during times of freezing weather. County councils, road authorities and private road operators apply road salt as required as part of their winter road maintenance programs. The road salt used is predominantly sodium chloride (NaCl) as it is relatively inexpensive when compared to other de-icing agents, easy to manufacture and readily available. A number of negative environmental effects and a loss in water quality have been associated with stormwater (melt water) containing dissolved road salt entering fresh waterbodies in the vicinity of roads which are de-iced with sodium chloride. -

Sean Boyle Architects Unit 3 Second Floor Donohue Building

Sean Boyle Architect F.G.I.S F.A.S.I. M.I.I.A.S EurGeo. Reg No.2251 Sean Boyle Architects Unit 3 Second Floor Donohue Building Kennedy Road, Navan, Co Meath. EIR Code: C15 PF77 T: 0469023797 Surveyors & Planners E: [email protected] VAT No. IE 7586274V LANDSCAPE & VISUAL IMPACT ASSESSMENT FOR RESTORATION OF EXISTING QUARRY FILL WITH INERT SOIL AND STONE AND Provision of a Public Amenity PARK For inspection purposes only. Consent of copyright owner required for any other use. AT TULLYKANE KILMESSAN CO. MEATH 1 EPA Export 21-04-2017:03:19:34 Table of Contents Pg. 1.0 Introduction 3 1.1 Background 3 1.2 Scope of Work 4 1.3 Planning Policy 5 1.4 Author 6 2.0 Receiving Environment 7 2.1 Baseline Study Methodology 7 2.2 Landscape Baseline 15 2.3 Visual Baseline 23 2.4 Difficulties Encountered 24 3.0 Impact Assessment 25 3.1 Evaluation Methodology 25 3.2 Landscape Impacts 30 3.3 Visual Impacts 32 3.4 Impacts on Landscape and Planning Designations 34 3.5 “Do- Nothing” Scenario 36 4.0 Mitigation Measures 37 5.0 Residual Impact 37 6.0 References For inspection purposes only. 37 Consent of copyright owner required for any other use. 2 EPA Export 21-04-2017:03:19:34 1. INTRODUCTION 1.1 BACKGROUND This section assesses the landscape & visual impacts arising from the proposed restoration, back fill and the provision of a community amenity park a Quarry at Tullykane, Kilmessan, Co. Meath including assessment of the following: Landscape Impacts, including: direct impacts upon specific landscape elements within and adjacent to the site; effects on the overall pattern of the landscape elements which give rise to the landscape character of the site and its surroundings; and impacts upon any special interests in and around the site. -

Major Roads Projects Active List Transport Infrastructure Ireland (TII) September 2020 Foreword

Major Roads Projects Active List Transport Infrastructure Ireland (TII) September 2020 Foreword Photo of Michael Nolan I am pleased to introduce TII’s Major Roads Projects Active List, the authoritative guide to the major roads projects’ falling under this capital investment programme over the coming years. TII performs an essential role in the delivery of transport infrastructure in Ireland, of which the national primary and secondary road networks have a significant function. The upgrade, maintenance and development of Ireland’s road network is a critical enabler of economic growth, as well as enabling the realisation of some of the National Strategic Outcomes and Strategic Investment Priorities of the National Development Plan and the National Planning Framework. It has been said that roads represent the first “social network”. They are fundamental building blocks for economic growth, access to services and social cohesion and support the transition to a low carbon future. The NPF recognises the need to rebalance opportunity by enhancing regional accessibility and strengthening rural economies and communities. Another determinant in seeking to upgrade sections of the unimproved roads network is to reduce the risk and number of collisions, injuries and deaths on our road infrastructure. Ireland has witnessed the upgrade of significant parts of the road network; however, unimproved sections are experiencing substantial numbers of people being seriously injured or killed, with increasing numbers of head-on collisions on our single carriageway national primary roads. I welcome the development of this first edition of the Active List. This list includes a one-page summary for each project setting out its national significance. -

1117 20-3 Kzng13

KWAZULU-NATAL PROVINCE RKEPUBLICWAZULU-NATAL PROVINSIEREPUBLIIEK OF VAN SOUTHISIFUNDAZWEAFRICA SAKWAZULUSUID-NATALI-AFRIKA Provincial Gazette • Provinsiale Koerant • Igazethi Yesifundazwe GAZETTE EXTRAORDINARY—BUITENGEWONE KOERANT—IGAZETHI EYISIPESHELI (Registered at the post office as a newspaper) • (As ’n nuusblad by die poskantoor geregistreer) (Irejistiwee njengephephandaba eposihhovisi) PIETERMARITZBURG, 20 MARCH 2014 Vol. 8 20 MAART 2014 No. 1117 20 kuNDASA 2014 We oil hawm he power to preftvent kllDc AIDS HEIRINE 0800 012 322 DEPARTMENT OF HEALTH Prevention is the cure N.B. The Government Printing Works will not be held responsible for the quality of “Hard Copies” or “Electronic Files” submitted for publication purposes 401207—A 1117—1 2 Extraordinary Provincial Gazette of KwaZulu-Natal 20 March 2014 IMPORTANT NOTICE The Government Printing Works will not be held responsible for faxed documents not received due to errors on the fax machine or faxes received which are unclear or incomplete. Please be advised that an “OK” slip, received from a fax machine, will not be accepted as proof that documents were received by the GPW for printing. If documents are faxed to the GPW it will be the sender’s respon- sibility to phone and confirm that the documents were received in good order. Furthermore the Government Printing Works will also not be held responsible for cancellations and amendments which have not been done on original documents received from clients. Page No. ADVERTISEMENT Road Carrier Permits, Pietermaritzburg........................................................................................................................ -

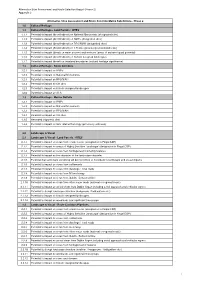

Appendix 3: List of Sub-Criteria

Alternative Sites Assessment and Route Selection Report (Phase 2) Appendix 3 Alternative Sites Assessment and Route Selection Matrix Sub-Criteria - Phase 2 1.0 Cultural Heritage 1.1 Cultural Heritage - Land Parcels / SITES 1.1.1 Potential to impact (direct/indirect) on National Monuments (designated sites) 1.1.2 Potential to impact (direct/indirect) on RMPs (designated sites) 1.1.3 Potential to impact (direct/indirect) on RPS/NIAH (designated sites) 1.1.4 Potential to impact (direct/indirect) on CH sites (previously unrecorded sites) 1.1.5 Potential to impact (direct) on water courses and environs (areas of archaeological potential) 1.1.6 Potential to impact (direct/indirect) on historic designed landscapes 1.1.7 Potential to impact (direct) on townland boundaries (cultural heritage significance) 1.2 Cultural Heritage - Route Corridors 1.2.1 Potential to impact on RMPs 1.2.2 Potential to impact on National Monuments 1.2.3 Potential to impact on RPS/NIAH 1.2.4 Potential to impact on CH sites 1.2.5 Potential to impact on historic designed landscapes 1.2.6 Potential to impact on ACA 1.3 Cultural Heritage - Marine Outfalls 1.3.1 Potential to impact on RMPs 1.3.2 Potential to impact on National Monuments 1.3.3 Potential to impact on RPS/NIAH 1.3.4 Potential to impact on CH sites 1.3.5 Recorded shipwreck sites 1.3.6 Potential to impact on inter-tidal archaeology (previously unknown) 2.0 Landscape & Visual 2.1 Landscape & Visual - Land Parcels / SITES 2.1.1 Potential to impact on views from scenic routes (designation in Fingal CDP) 2.1.2 Potential