Research Framework for London Archaeology MOLA 2002

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Reign and Coinage of Carausius

58 REIGN AND COINAGE OF CARAUSIUS. TABLE OF MINT-MARKS. 1. MARKS ATTRIBUTABLE TO COLCHESTER.. Varietyor types noted. Marki. Suggested lnterretatlona.p Carauslna. Allectus. N JR IE N IE Cl· 6 3 The mark of Ce.mulodunum.1 • � I Ditto ·I· 2(?) 93 Ditto 3 Ditto, blundered. :1..:G :1..: 3 Ditto, retrograde. ·I· I Stukeley, Pl. uix. 2, probably OLA misread. ·I· 12 Camulodunum. One 21st part CXXI of a denarius. ·I· 26 Moneta Camulodunensis. MC ·I· I MC incomplete. 1 Moueta Camuloduuensis, &o. MCXXI_._,_. ·I· 5 1 Mone� . eignata Camulodu- MSC nene1s. __:.l_:__ 3 Moneta signata Ooloniae Ca- MSCC muloduneneie. I· 1 Moneta signata Ooloniae. MSCL ·I· I MCXXI blundered. MSXXI ·I· 1 1 Probably QC blundered. PC ·I· I(?; S8 Quinariue Camuloduneneis.11 cQ • 10 The city mark is sometimes found in the field on the coinage of Diocletian. 11 Cf. Num. Ohron., 1906, p. 132. MINT-MARKS. 59 MABKS ATTRIBUTABLE TO COLCHESTER-continued. Variety of types noted. Jl!arks. Suggested Interpretation•. Carauslus. Allectus. N IR IE. A/ IE. ·I· I Signata Camuloduni. SC ·I· 1 Signata. moneta Camulodu- SMC nensis. •I· I Signo.ta moneta Caruulodu- SMC nensis, with series mark. ·I· 7 4 Signata prima (offlcina) Ca- SPC mulodnnens�. ·I· 2 The 21st part of a donarius. XXIC Camulodunum. BIE I Secundae (offlcinac) emissa, CXXI &c. ·IC I Tortfo (offlcina) Camulodu- nensis. FIO I(?' Faciunda offlcina Camulodu- � nensis . IP 1 Prima offlcina Camulo,lu- � nensis. s I. 1 1 Incomplete. SIA 1 Signata prima (offlcina) Camu- lodunensis. SIA I Signata prima (officina) Co- CL loniae. -

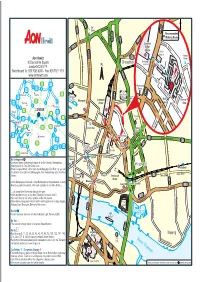

Aon Hewitt-10 Devonshire Square-London EC2M Col

A501 B101 Old C eet u Street Str r t A1202 A10 ld a O S i n Recommended h o A10 R r Walking Route e o d et G a tre i r d ld S e t A1209 M O a c Liverpool iddle t h sex Ea S H d Street A5201 st a tre e i o A501 g e rn R Station t h n S ee Police tr S Gr Station B e e t nal Strype u t Beth B134 Aon Hewitt C n Street i t h C y Bishopsgate e i l i t N 10 Devonshire Square l t Shoreditch R a e P y East Exit w R N L o iv t Shoreditcher g S St o Ra p s t London EC2M 4YP S oo re pe w d l o e y C S p t tr h S a tr o i A1202 e t g Switchboard Tel: 020 7086 8000 - Fax: 020 7621 1511 d i e h M y t s H i D i R d www.aonhewitt.com B134 ev h B d o on c s Main l a h e t i i r d e R Courtyard s J21 d ow e e x A10 r W Courtyard M11 S J23 B100 o Wormwood Devonshire Sq t Chis h e r M25 J25 we C c e l S J27 l Str Street a e M1 eet o l t Old m P Watford Barnet A12 Spitalfields m A10 M25 Barbican e B A10 Market w r r o c C i Main r Centre Liverpool c a r Harrow Pl A406 J28 Moorgate i m a k a e t o M40 J4 t ld S m Gates C Harrow hfie l H Gate Street rus L i u a B le t a H l J1 g S e J16 r o J1 Romford n t r o e r u S e n tr A40 LONDON o e d e M25 t s e Slough M t A13 S d t it r c A1211 e Toynbee h J15 A13 e M4 J1 t Hall Be J30 y v Heathrow Lond ar is on W M M P all e xe Staines A316 A205 A2 Dartford t t a London Wall a Aldgate S A r g k J1 J2 s East s J12 Kingston t p Gr S o St M3 esh h h J3 am d s Houndsditch ig Croydon Str a i l H eet o B e e A13 r x p t Commercial Road M25 M20 a ee C A13 B A P h r A3 c St a A23 n t y W m L S r n J10 C edldle a e B134 M20 Bank of e a h o J9 M26 J3 heap adn Aldgate a m sid re The Br n J5 e England Th M a n S t Gherkin A10 t S S A3 Leatherhead J7 M25 A21 r t e t r e e DLR Mansion S Cornhill Leadenhall S M e t treet t House h R By Underground in M c o Bank S r o a a Liverpool Street underground station is on the Central, Metropolitan, u t r n r d DLR h i e e s Whitechapel c Hammersmith & City and Circle Lines. -

Cutlers Court, 115 Houndsditch, London, EC3A 7BR 2,345 to 9,149 Sq Ft

jll.co.uk/property To Let Cutlers Court, 115 Houndsditch, London, EC3A 7BR 2,345 to 9,149 sq ft • Cost effective fitted out offices • Furniture packages available • Flexible working space • Manned reception Location EPC The building is located on the north side of Houndsditch. 115 This property has been graded as E (122). Houndsditch benefits from excellent access to public transport being 3 minutes from Liverpool Street station, 4 minutes from Rent Aldgate tube station and 8 minutes from Bank Station. The £19.50 per sq ft property is situated within close proximity to Lloyd’s of London exclusive of rates, service charge and VAT (if applicable). and Broadgate and is moments from the amenities of Devonshire Square and Spitalfields. Business Rates Rates payable: £14.77 per sq ft Specification The Ground and 4th floors are available with high quality fit Service Charge outs in situ as follows: £11.85 per sq ft Ground floor EC3A 7BR - 1 x 8 person meeting room - 1 x 6 person meeting room - 1 x 4 person meeting room - Kitchen/breakout area - Cat 6 Data Cabling 4th floor - 1 x 10 person meeting room - 2 x 8 person meeting rooms - 2 on floor showers - Kitchen/breakout area - New floor outlet boxes and underfloor CAT 6 data cabling Terms New lease available from the Landlord (term certain until June Contacts 2023). Nick Lines 0207 399 5693 Viewings [email protected] Viewing via the sole agents only. Nick Going Accommodation [email protected] Floor/Unit Sq ft Rent Availability 4th 6,804 £19.50 per sq ft Available Ground 2,345 £19.50 per sq ft Available Total 9,149 JLL for themselves and for the vendors or lessors of this property whose agents they are, give notice that:- a. -

Strategic Stone Study a Building Stone Atlas of Cambridgeshire (Including Peterborough)

Strategic Stone Study A Building Stone Atlas of Cambridgeshire (including Peterborough) Published January 2019 Contents The impressive south face of King’s College Chapel, Cambridge (built 1446 to 1515) mainly from Magnesian Limestone from Tadcaster (Yorkshire) and Kings Cliffe Stone (from Northamptonshire) with smaller amounts of Clipsham Stone and Weldon Stone Introduction ...................................................................................................................................................... 1 Cambridgeshire Bedrock Geology Map ........................................................................................................... 2 Cambridgeshire Superficial Geology Map....................................................................................................... 3 Stratigraphic Table ........................................................................................................................................... 4 The use of stone in Cambridgeshire’s buildings ........................................................................................ 5-19 Background and historical context ........................................................................................................................................................................... 5 The Fens ......................................................................................................................................................................................................................... 7 South -

Boats, Bangs, Bricks and Beer a Self-Guided Walk Along Faversham Creek

Boats, bangs, bricks and beer A self-guided walk along Faversham Creek Explore a town at the head of a creek Discover how creek water influenced the town’s prosperity Find out about the industries that helped to build Britain .discoveringbritain www .org ies of our land the stor scapes throug discovered h walks 2 Contents Introduction 4 Route overview 5 Practical information 6 Detailed route maps 8 Commentary 10 Credits 38 © The Royal Geographical Society with the Institute of British Geographers, London, 2012 Discovering Britain is a project of the Royal Geographical Society (with IBG) The digital and print maps used for Discovering Britain are licensed to the RGS-IBG from Ordnance Survey 3 Boats, bangs, bricks and beer Discover how Faversham Creek helped to build Britain Faversham on the East Kent coast boasts the best-preserved medieval street in England, the country’s oldest brewery, helped us win the Battle of Trafalgar and has a justifiable claim to be ‘the town that built Britain’. So what’s it’s secret? Early settlers were the first to recognise its prime waterside location and a settlement quickly grew up here at the head of the navigable creek, with quick and easy access to Europe in one direction and London in the other. The soil around the creeks and rivers was rich and fertile, pure spring water was readily available from local aquifers, and the climate was dry and temperate. Sailing ships in Faversham Creek Caroline Millar © RGS-IBG Discovering Britain This gentle creekside walk takes you on a journey of discovery from the grand Victorian station through the medieval centre of town then out through its post-industrial edgelands to encounter the bleak beauty of the Kent marshes. -

Diocletian's New Empire

1 Diocletian's New Empire Eutropius, Brevarium, 9.18-27.2 (Eutr. 9.18-27.2) 18. After the death of Probus, CARUS was created emperor, a native of Narbo in Gaul, who immediately made his sons, Carinus and Numerianus, Caesars, and reigned, in conjunction with them, two years. News being brought, while he was engaged in a war with the Sarmatians, of an insurrection among the Persians, he set out for the east, and achieved some noble exploits against that people; he routed them in the field, and took Seleucia and Ctesiphon, their noblest cities, but, while he was encamped on the Tigris, he was killed by lightning. His son NUMERIANUS, too, whom he had taken with him to Persia, a young man of very great ability, while, from being affected with a disease in his eyes, he was carried in a litter, was cut off by a plot of which Aper, his father-in-law, was the promoter; and his death, though attempted craftily to be concealed until Aper could seize the throne, was made known by the odour of his dead body; for the soldiers, who attended him, being struck by the smell, and opening the curtains of his litter, discovered his death some days after it had taken place. 19. 1. In the meantime CARINUS, whom Carus, when he set out to the war with Parthia, had left, with the authority of Caesar, to command in Illyricum, Gaul, and Italy, disgraced himself by all manner of crimes; he put to death many innocent persons on false accusations, formed illicit connexions with the wives of noblemen, and wrought the ruin of several of his school-fellows, who happened to have offended him at school by some slight provocation. -

Liverpool Street Bus Station Closure

Liverpool Street bus station closed - changes to routes 11, 23, 133, N11 and N133 The construction of the new Crossrail ticket hall in Liverpool Street is progressing well. In order to build a link between the new ticket hall and the Underground station, it will be necessary to extend the Crossrail hoardings across Old Broad Street. This will require the temporary closure of the bus station from Sunday 22 November until Spring 2016. Routes 11, 23 and N11 Buses will start from London Wall (stop ○U) outside All Hallows Church. Please walk down Old Broad Street and turn right at the traffic lights. The last stop for buses towards Liverpool Street will be in Eldon Street (stop ○V). From there it is 50 metres to the steps that lead down into the main National Rail concourse where you can also find the entrance to the Underground station. Buses in this direction will also be diverted via Princes Street and Moorgate, and will not serve Threadneedle Street or Old Broad Street. Routes 133 and N133 The nearest stop will be in Wormwood Street (stop ○Q). Please walk down Old Broad Street and turn left along Wormwood Street after using the crossing to get to the opposite side of the road. The last stop towards Liverpool Street will also be in Wormwood Street (stop ○P). Changes to routes 11, 23, 133, N11 & N133 Routes 11, 23, 133, N11 & N133 towards Liverpool Street Routes 11 & N11 towards Bank, Aldwych, Victoria and Fulham Route 23 towards Bank, Aldwych, Oxford Circus and Westbourne Park T E Routes 133 & N133 towards London Bridge, Elephant & Castle, -

The Political and Military Aspects of Accession of Constantine the Great

Graeco-Latina Brunensia 24 / 2019 / 2 https://doi.org/10.5817/GLB2019-2-2 The Political and Military Aspects of Accession of Constantine the Great Stanislav Doležal (University of South Bohemia in České Budějovice) Abstract The article argues that Constantine the Great, until he was recognized by Galerius, the senior ČLÁNKY / ARTICLES Emperor of the Tetrarchy, was an usurper with no right to the imperial power, nothwithstand- ing his claim that his father, the Emperor Constantius I, conferred upon him the imperial title before he died. Tetrarchic principles, envisaged by Diocletian, were specifically put in place to supersede and override blood kinship. Constantine’s accession to power started as a military coup in which a military unit composed of barbarian soldiers seems to have played an impor- tant role. Keywords Constantine the Great; Roman emperor; usurpation; tetrarchy 19 Stanislav Doležal The Political and Military Aspects of Accession of Constantine the Great On 25 July 306 at York, the Roman Emperor Constantius I died peacefully in his bed. On the same day, a new Emperor was made – his eldest son Constantine who had been present at his father’s deathbed. What exactly happened on that day? Britain, a remote province (actually several provinces)1 on the edge of the Roman Empire, had a tendency to defect from the central government. It produced several usurpers in the past.2 Was Constantine one of them? What gave him the right to be an Emperor in the first place? It can be argued that the political system that was still valid in 306, today known as the Tetrarchy, made any such seizure of power illegal. -

The Cambridge Companion to Age of Constantine.Pdf

The Cambridge Companion to THE AGE OF CONSTANTINE S The Cambridge Companion to the Age of Constantine offers students a com- prehensive one-volume introduction to this pivotal emperor and his times. Richly illustrated and designed as a readable survey accessible to all audiences, it also achieves a level of scholarly sophistication and a freshness of interpretation that will be welcomed by the experts. The volume is divided into five sections that examine political history, reli- gion, social and economic history, art, and foreign relations during the reign of Constantine, a ruler who gains in importance because he steered the Roman Empire on a course parallel with his own personal develop- ment. Each chapter examines the intimate interplay between emperor and empire and between a powerful personality and his world. Collec- tively, the chapters show how both were mutually affected in ways that shaped the world of late antiquity and even affect our own world today. Noel Lenski is Associate Professor of Classics at the University of Colorado, Boulder. A specialist in the history of late antiquity, he is the author of numerous articles on military, political, cultural, and social history and the monograph Failure of Empire: Valens and the Roman State in the Fourth Century ad. Cambridge Collections Online © Cambridge University Press, 2007 Cambridge Collections Online © Cambridge University Press, 2007 The Cambridge Companion to THE AGE OF CONSTANTINE S Edited by Noel Lenski University of Colorado Cambridge Collections Online © Cambridge University Press, 2007 cambridge university press Cambridge, New York, Melbourne, Madrid, Cape Town, Singapore, Sao˜ Paulo Cambridge University Press 40 West 20th Street, New York, ny 10011-4211, usa www.cambridge.org Information on this title: www.cambridge.org/9780521818384 c Cambridge University Press 2006 This publication is in copyright. -

Irongate House, Houndsditch EC3 Ruth Siddall Irongate

Urban Geology in London No. 24 Meteorite Impactites in London: Irongate House, Houndsditch EC3 Ruth Siddall Irongate House (below) was designed by architects Fitzroy, Robinson & Partners and completed in 1978. It is a building that is quite easy to ignore. Situated at the Aldgate end of Houndsditch in the City of London, this is a now rather dated, 1970s office block surrounded, and arguably encroached upon by the sparkling glass slabs and cylinders of new modern blocks nicknamed the ‘Gherkin’ and the ‘Cheesegrater’. Walking past, at pavement level, it could indeed be dismissed as the entrance to an underground car park. But look up! Irongate House is a geological gem with a unique and spectacular decorative stone used for cladding the façade. Eric Robinson corresponded with the architects during the building of Irongate House, whilst he was compiling his urban geological walk from the Royal Exchange to Aldgate (Robinson, 1982) and the second volume of the London: Illustrated Geological Walks (Robinson, 1985). Eric discovered that Fitzroy, Robinson & Partners’ stone contractors had chosen a most exotic, unusual and unexpected rock, newly available on the market. This is an orthogneiss from South Africa called the Parys Gneiss. What makes this rock more interesting is that the town of Parys, where the quarries are located, is positioned close to the centre of a major meteorite impact crater, the Vredefort Dome, and the effects of this event, melts associated with the impact called pseudotachylites, cross-cut the gneiss and can be observed here in the City of London. Both to mine and Eric’s knowledge, Parys Gneiss is used here uniquely in the UK, and as such it also made it into Ashurst & Dimes (1998)’s review of building stones. -

A Tale of Two Periods

A tale of two periods Change and continuity in the Roman Empire between 249 and 324 Pictured left: a section of the Naqš-i Rustam, the victory monument of Shapur I of Persia, showing the captured Roman emperor Valerian kneeling before the victorious Sassanid monarch (source: www.bbc.co.uk). Pictured right: a group of statues found on St. Mark’s Basilica in Venice, depicting the members of the first tetrarchy – Diocletian, Maximian, Constantius and Galerius – holding each other and with their hands on their swords, ready to act if necessary (source: www.wikipedia.org). The former image depicts the biggest shame suffered by the empire during the third-century ‘crisis’, while the latter is the most prominent surviving symbol of tetrar- chic ideology. S. L. Vennik Kluut 14 1991 VB Velserbroek S0930156 RMA-thesis Ancient History Supervisor: Dr. F. G. Naerebout Faculty of Humanities University of Leiden Date: 30-05-2014 2 Table of contents Introduction ............................................................................................................................................. 3 Sources ............................................................................................................................................ 6 Historiography ............................................................................................................................... 10 1. Narrative ............................................................................................................................................ 14 From -

Bishopsgate Conservation Area Draft Character Summary and Management Strategy SPD

City of London Bishopsgate Conservation Area Draft Character Summary and Management Strategy SPD Bishopsgate CA Draft Character Summary and Management Strategy SPD – Jan 2014 1 Introduction Character summary 1. Location and context 2. Designation history 3. Summary of character 4. Historical development Early history Eighteenth and nineteenth centuries Twentieth and twenty-first centuries 5. Spatial analysis Layout and plan form Building plots Building heights Views and vistas 6. Character analysis Bishopsgate Bishopsgate courts and alleys St Botolph without Bishopsgate Church and Churchyard Liverpool Street/Old Broad Street Wormwood Street Devonshire Row Devonshire Square New Street Middlesex Street Widegate Street Artillery Lane and Sandy’s Row Brushfield Street and Fort Street 7. Land uses and related activity 8. Traffic and transport 9. Architectural character Architects, styles and influences Building ages 10. Local details Architectural sculpture Public statuary and other features Blue plaques Historic signs Signage and shopfronts 11. Building materials 12. Open spaces and trees 13. Public realm 14. Cultural associations Bishopsgate CA Draft Character Summary and Management Strategy SPD – Jan 2014 2 Management strategy 15. Planning policy 16. Access and an inclusive environment 17. Environmental enhancement 18. Management of transport 19. Management of open spaces and trees 20. Archaeology 21. Enforcement 22. Condition of the conservation area Further reading and references Appendix Designated heritage assets Contacts Bishopsgate CA Draft Character Summary and Management Strategy SPD – Jan 2014 3 Introduction The present urban form and character of the City of London has evolved over many centuries and reflects numerous influences and interventions: the character and sense of place is hence unique to that area, contributing at the same time to the wider character of London.