Captain Graham on Irish Wolfhounds

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Pdf File of the Complete Population of Between 400 and 800 Eventually Leading to Large Areas Being Devoid Article

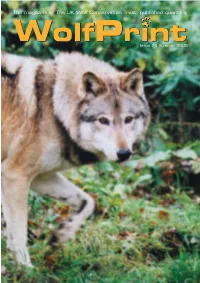

The magazine of The UK Wolf Conservation Trust, published quarterly Issue 24 Summer 2005 Published by: The UK Wolf Conservation Trust Butlers Farm, Beenham, Reading RG7 5NT Tel & Fax: 0118 971 3330 e-mail: [email protected] www.ukwolf.org ditorial Editor Denise Taylor E Tel: 01788 832658 e-mail: [email protected] Editorial Team n preparation for the UKWCT Autumn seminar one of our regular contributors, Julia Bohanna,Andrew Matthews, Kirsty Peake, has written about her trip to the Yellowstone National Park in February Gwynne Power, Sue Sefscik Ithis year. Her article gives us a good introduction to George Bumann, one of the Contributors to this issue: speakers at the seminar, who was with Kirsty’s party during the trip. Keeping with the Pat Adams, Chris Darimont, Chris Genovali, Yellowstone theme, wolf biologist Doug Smith’s book, Decade of the Wolf, was Kieran Hickey, Bill Lynn, Faisal Moola, Paul Paquet, published in April and covers the last ten years in Yellowstone. To order your copy see Kirsty Peake. the back inside cover of this issue. Copies will also be available at the seminar. I am delighted to announce the start of a new syndicated column, Ethos,by Senior Design and Artwork: Phil Dee Tel:01788 546565 Ethics Advisor Bill Lynn on ethics and wildlife. This will be a regular feature, and is designed to make us stop and think about our attitudes and actions towards others, Patrons and especially towards a species that provokes strong emotions. We invite you to Desmond Morris reflect on the more philosophical, but nevertheless fundamental, aspects of wolf Erich Klinghammer conservation, and to let us have your comments and views. -

From Wolves to Dogs, and Back: Genetic Composition of the Czechoslovakian Wolfdog

RESEARCH ARTICLE From Wolves to Dogs, and Back: Genetic Composition of the Czechoslovakian Wolfdog Milena Smetanová1☯, Barbora Černá Bolfíková1☯*, Ettore Randi2,3, Romolo Caniglia2, Elena Fabbri2, Marco Galaverni2, Miroslav Kutal4,5, Pavel Hulva6,7 1 Faculty of Tropical AgriSciences, Czech University of Life Sciences Prague, Prague, Czech Republic, 2 Laboratorio di Genetica, Istituto Superiore per la Protezione e Ricerca Ambientale (ISPRA), Ozzano Emilia (BO), Italy, 3 Department 18/Section of Environmental Engineering, Aalborg University, Aalborg, Denmark, 4 Institute of Forest Ecology, Faculty of Forestry and Wood Technology, Mendel University in Brno, Brno, Czech Republic, 5 Friends of the Earth Czech Republic, Olomouc branch, Olomouc, Czech Republic, 6 Department of Zoology, Charles University in Prague, Prague, Czech Republic, 7 Department of Biology and Ecology, Ostrava University, Ostrava, Czech Republic ☯ These authors contributed equally to this work. * [email protected] Abstract OPEN ACCESS The Czechoslovakian Wolfdog is a unique dog breed that originated from hybridization between German Shepherds and wild Carpathian wolves in the 1950s as a military experi- Citation: Smetanová M, Černá Bolfíková B, Randi E, ment. This breed was used for guarding the Czechoslovakian borders during the cold war Caniglia R, Fabbri E, Galaverni M, et al. (2015) From Wolves to Dogs, and Back: Genetic Composition of and is currently kept by civilian breeders all round the world. The aim of our study was to the Czechoslovakian Wolfdog. PLoS ONE 10(12): characterize, for the first time, the genetic composition of this breed in relation to its known e0143807. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0143807 source populations. We sequenced the hypervariable part of the mtDNA control region and Editor: Dan Mishmar, Ben-Gurion University of the genotyped the Amelogenin gene, four sex-linked microsatellites and 39 autosomal micro- Negev, ISRAEL satellites in 79 Czechoslovakian Wolfdogs, 20 German Shepherds and 28 Carpathian Received: July 22, 2015 wolves. -

The 7Pm Zoomies I Don’T Know What It Is

The REACH Reader Volume 1. Issue 1 Welcome to the first volume of the REACH Reader! Here you will find funny stories, useful tips, training games and client successes. The 7pm Zoomies I don’t know what it is. Every evening. My furry , four-legged night, around the same time, no furniture movers have run of the matter what’s going on, my dogs house, and their antics usually decide to take laps around the just make me laugh – but if you house. This sudden burst of are in a situation where it could energy overtakes them, and they cause an issue; there’s a Have a picture or story you’d like to act like lunatics for a few minutes relatively easy solution. see included? Send it to us! every night. When I talked to other people; I found out that Since the timing is consistent; [email protected] their dogs also got a little nutty let’s say for the sake of example at a certain time every day! I’ve 7:00, just plan an activity that ts March 4, 2017 n dubbed it the 7pm zoomies and starts at 6:50 and lasts about 15 e v CGC & CLASS test day I have no explanation for it. For minutes. This could be training, E most people, this phenomenon a short walk, or even a game of occurs between 6-8:00 in the hide and seek. Just give your pup Dates to Know: something physically active to do during his Zoomie time, and Jan 14 - National Dress Up Your Pet Day peace will be restored! Jan 21 - Squirrel Appreciation Day Does your dog get the 7pm Feb 20 - National Love Your Pet Day zoomies? Let us know! Feb 23 - National Dog Biscuit Day Mar 13 - National K9 Veterans Day Mar 23 - National Puppy Day The REACH Reader | Winter 2017 Issue 1 The Reach Reader | Quarterly Newsletter Story Some days… I’m a trainer, so I must have some pretty awesome dogs, right? Well – I do have awesome dogs, but they aren’t perfect. -

Sherkin Comment

SHERKIN COMMENT Issue No. 56 Environmental Quarterly of Sherkin Island Marine Station 2013 Sherkin Island – A Local History Coming Together for Henry Ford’s The Irish Group Water Scheme Sector Mask, snorkel and fins = adventure! Dolly O’Reilly’s new book takes an historical 150th Birthday Brian Mac Domhnaill explains how vital Pete Atkinson explains the joy of look at the island’s social, cultural & A public celebration at the historic Henry Ford this sector has been for rural Ireland. snorkelling in shallow waters. economic life. 4 Estate in Dearborn, Michigan, USA. 6 10 16/17 INSIDE Ireland’s Birds Lost and Gained Greenshank in Kinish Harbour, Sherkin Island. Photographer: Robbie Murphy 2 ______________________________________________________________________________________________________ SHERKIN COMMENT 2013 Issue No 56 Contents Editorial EDITORIAL: Getting Back to Basics......................2 Matt Murphy looks back at some of the lessons learned in his youth. Ireland’s Birds – Lost and Gained ............................3 Getting Back to Basics Oscar Merne on our ever-changing bird population. Sherkin Island – A Local History ............................4 change our mindset when shopping. Dolly O’Reilly’s new book takes an historical look By Matt Murphy The Stop Food Waste campaign (fea- at the island’s social, cultural & economic life. tured in Sherkin Comment No. 52 – Plants and Old Castles ............................................5 I AM from a generation that in the 1940s www.stopfoodwaste.ie) is a really worth- John Akeroyd explains why old buildings & ruins and 50s carefully untied the knots in the while campaign. It highlight some twine and carefully folded the brown are happy hunting grounds for botanists. interesting reasons why we waste food: paper for reuse from any parcels that • Coming Together for Henry Ford’s 150th Birthday ..6 We do not make a list before shopping. -

Dog Breeds of the World

Dog Breeds of the World Get your own copy of this book Visit: www.plexidors.com Call: 800-283-8045 Written by: Maria Sadowski PlexiDor Performance Pet Doors 4523 30th St West #E502 Bradenton, FL 34207 http://www.plexidors.com Dog Breeds of the World is written by Maria Sadowski Copyright @2015 by PlexiDor Performance Pet Doors Published in the United States of America August 2015 All rights reserved. No portion of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means, including photocopying, recording, or by any information retrieval and storage system without permission from PlexiDor Performance Pet Doors. Stock images from canstockphoto.com, istockphoto.com, and dreamstime.com Dog Breeds of the World It isn’t possible to put an exact number on the Does breed matter? dog breeds of the world, because many varieties can be recognized by one breed registration The breed matters to a certain extent. Many group but not by another. The World Canine people believe that dog breeds mostly have an Organization is the largest internationally impact on the outside of the dog, but through the accepted registry of dog breeds, and they have ages breeds have been created based on wanted more than 340 breeds. behaviors such as hunting and herding. Dog breeds aren’t scientifical classifications; they’re It is important to pick a dog that fits the family’s groupings based on similar characteristics of lifestyle. If you want a dog with a special look but appearance and behavior. Some breeds have the breed characterics seem difficult to handle you existed for thousands of years, and others are fairly might want to look for a mixed breed dog. -

Your New Rescue Dog

National Great Pyrenees Rescue - 1 - Your New Rescue Dog Thank you giving a home to a rescue dog! By doing so, you have saved a life. It takes many volunteers and tremendous amounts of time and effort to save each dog. Please remember each and every one of them is special to us and we want the best for them. As such, we want you to be happy with your dog. No dog is perfect, and a rescue dog may require time and patience to reach their full potential, but they will reward you a hundred times over. Be patient, be firm, but most of all have fun and enjoy your new family member! Meeting a transport Traveling on a commercial or multi-legged volunteer transport is very stressful for dogs. Many will not eat or drink while traveling, so bring water and a bowl to the meeting place. Have a leash and name tag ready with your contact info and put these on the dog ASAP. No one wants to see a dog lost, especially after going through so much to get to you. Take your new Pyr for a walk around the parking lot. It’s tempting to cuddle a new dog, but what they really need is some space. They will let you know when they are ready for attention. Puppies often need to be carried at first, but they do much better once they feel grass under their feet. Young puppies should not be placed on the ground at transport meeting locations. Their immune system may not be ready for this. -

Florida Lupine News

Florida Lupine NEWs Volume 9, Issue 4 Winter 2007 Published Quarterly FLA 2008 Rendezvous: April 18 - 20 for Members. Free to FLA's 2008 Rendezvous will be held Fri- of the Fish and Wildlife Commission and Veterinarians, day, April 18 through Sunday, April 20, at FWC Law Enforcement component, the Tech- Parramore's Resort and Campgrounds. Those nical Assistant Group (TAG). Three board Shelters, Donors, of you who attended last year know how hospi- members have also attended FWC meetings Sponsors, Rescues, table the staff members at Parramore's were, to get a handle on how the current trends re- and Animal Welfare & how receptive they were to our members and garding captive wildlife (including wolfdogs) their dogs. If you didn't make last year's Ren- may be heading, and the Board will outline Control Agencies. dezvous, which also functions as FLA's annual the information it has available by the time of meeting, you have another opportunity this the Rendezvous. (At least one board member year to visit this beautiful, not to mention ca- will try to attend any FWC meetings which FLA Directors nine welcoming, venue. We are more than for- may be held being prior to the Rendezvous.) tunate to find a facility that will still allow Al Mitchell, President Among the rules which FWC is drafting large canines in the cabins and on the premises. or is considering are "Neighbor Notification," Mayo Wetterberg Located on the St. John's River, near Astor, "dangerous" captive wildlife, and new mini- Andrea Bannon Parramore's provides all we could ask for and mum acreage and fencing requirements for Jill Parker then some. -

Wolf Outside, Dog Inside? the Genomic Make-Up of the Czechoslovakian Wolfdog

Aalborg Universitet Wolf outside, dog inside? The genomic make-up of the Czechoslovakian Wolfdog Caniglia, Romolo; Fabbri, Elena; Hulva, Pavel; Bolfíková, Barbora erná; Jindichová, Milena; Strønen, Astrid Vik; Dykyy, Ihor; Camatta, Alessio; Carnier, Paolo; Randi, Ettore; Galaverni, Marco Published in: B M C Genomics DOI (link to publication from Publisher): 10.1186/s12864-018-4916-2 Creative Commons License CC BY 4.0 Publication date: 2018 Document Version Publisher's PDF, also known as Version of record Link to publication from Aalborg University Citation for published version (APA): Caniglia, R., Fabbri, E., Hulva, P., Bolfíková, B. ., Jindichová, M., Strønen, A. V., Dykyy, I., Camatta, A., Carnier, P., Randi, E., & Galaverni, M. (2018). Wolf outside, dog inside? The genomic make-up of the Czechoslovakian Wolfdog. B M C Genomics, 19(1), [533]. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12864-018-4916-2 General rights Copyright and moral rights for the publications made accessible in the public portal are retained by the authors and/or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. ? Users may download and print one copy of any publication from the public portal for the purpose of private study or research. ? You may not further distribute the material or use it for any profit-making activity or commercial gain ? You may freely distribute the URL identifying the publication in the public portal ? Take down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact us at [email protected] providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. -

Developing Dog Biscuits from Industrial By-Product Kyriaki Chanioti

Developing Dog Biscuits from Industrial by-product Kyriaki Chanioti DIVISION OF PACKAGING LOGISTICS | DEPARTMENT OF DESIGN SCIENCES FACULTY OF ENGINEERING LTH | LUND UNIVERSITY 2019 MASTER THESIS This Master’s thesis has been done within the Erasmus Mundus Joint Master Degree FIPDes, Food Innovation and Product Design. The European Commission support for the production of this publication does not constitute an endorsement of the contents which reflects the views only of the authors, and the Commission cannot be held responsible for any use which may be made of the information contained therein. Developing Dog Biscuits from Industrial by-product From an idea to prototype Kyriaki Chanioti Developing Dog Biscuit from Industrial by-product From an idea to prototype Copyright © 2019 Kyriaki Chanioti Published by Division of Packaging Logistics Department of Design Sciences Faculty of Engineering LTH, Lund University P.O. Box 118, SE-221 00 Lund, Sweden Subject: Food Packaging Design (MTTM01) Division: Packaging Logistics Supervisor: Daniel Hellström Co-supervisor: Federico Gomez Examiner: Klas Hjort This Master´s thesis has been done within the Erasmus Mundus Joint Master Degree FIPDes, Food Innovation and Product Design. www.fipdes.eu ISBN 978-91-7895-210-6 Acknowledgments It is happening, I am graduating FIPDes with the most fascinating thesis project that could ever imagine! However, I would like to firstly thank all the people in FIPDes consortium who believed in me and made my dream come true. The completion of this amazing project would not have been possible without the support, guidance and positive attitude of my supervisor, Daniel Hellström and my co-supervisor, Federico Gomez for making my stay in Kemicentrum welcoming and guiding me through the process. -

Foyle Heritage Audit NI Core Document

Table of Contents Executive Summary i 1 Introduction ..................................................................................................1 1.1 Purpose of Study ................................................................................................... 1 1.2 Objectives of the Audit ......................................................................................... 2 1.3 Project Team ......................................................................................................... 3 1.4 Study Area ............................................................................................................. 5 1.5 Divisions ................................................................................................................ 6 2 Audit Methodology .......................................................................................8 2.1 Identification of Sources ....................................................................................... 8 2.2 Pilot Study Area..................................................................................................... 9 2.3 Selection & Organisation of Data .......................................................................... 9 2.4 Asset Data Sheets ............................................................................................... 11 2.5 Consultation & Establishment of Significance .................................................... 11 2.6 Public Presentation ............................................................................................ -

The Illustrated Standard of the Irish Wolfhound

THE ILLUSTRATED STANDARD OF THE IRISH WOLFHOUND INTRODUCTION Irish Wolfhounds, according to legend and history, originated in those days long ago veiled in antiquity when bards and story tellers were the caretakers of history and the reporters of current events. One of the earliest recorded references to Irish Wolfhounds is in Roman records dating to 391 A.D. Often given as royal gifts, they hunted with their masters, fought beside them in battle, guarded their castles, played with their children, and laid quietly by the fire as family friends. They were fierce hunters of wolves and deer. Following a severe famine in the 1840s and the arrival of the shot gun that replaced the need for the Irish Wolfdog to control wolves, there were very few Irish Wolfhounds left in Ireland. It was in the mid 19th century that Captain George A. Graham gathered those specimens of the breed he could find and began a breeding program, working for 20 years to re-establish the Breed. The Standard of the Breed written by Captain Graham in 1885 is basically the standard to which we still adhere. Today’s hound seldom hunts live game, does not go to war, and is owned not only by the highly placed but also by the common man. Yet he still has that keen hunting instinct, guards his home and family, is a constant companion and friend, lies by the fire at night, and plays with the kids. Being a family companion has replaced his original, primary function as a hunting hound, but he will still, untrained to do so, give chase to fleeing prey. -

From Wolf to Dog: Behavioural Evolution During Domestication

FROM WOLF TO DOG: BEHAVIOURAL EVOLUTION DURING DOMESTICATION Christina Hansen Wheat From wolf to dog: Behavioural evolution during domestication Christina Hansen Wheat ©Christina Hansen Wheat, Stockholm University 2018 ISBN print 978-91-7797-272-3 ISBN PDF 978-91-7797-273-0 Printed in Sweden by Universitetsservice US-AB, Stockholm 2018 Distributor: Department of Zoology, Stockholm University Cover photo: "Iggy & Janis" ©Christina Hansen Wheat Gallery, all photos ©Christina Hansen Wheat “All his life he tried to be a good person. Many times, however, he failed. For after all, he was only human. He wasn’t a dog.” – Charles M. Schulz FROM WOLF TO DOG: BEHAVIOURAL EVOLUTION DURING DOMESTICATION - LIST OF PAPERS - The thesis is based on the following articles, which are referred to in the text by their Roman numerals: I Wheat C. Hansen, Fitzpatrick J. & Temrin H. Behaviours of the domestication syndrome are decoupled in modern dog breeds. Submitted manuscript, reviewed and in revision for Nature Communications II Wheat C. Hansen, Fitzpatrick J., Tapper I. & Temrin H. (2018). Wolf (Canis lupus) hybrids highlight the importance of human- directed play behaviour during domestication of dogs (Canis familiaris). Journal of Comparative Psychology, in press III Wheat C. Hansen, Berner P., Larsson I., Tapper I. & Temrin H. Key behaviours in the domestication syndrome do not develop simultaneously in wolves and dogs. Manuscript IV Wheat C. Hansen, Van der Bijl W. & Temrin H. Dogs, but not wolves, lose their sensitivity towards novelty with age. Manuscript. Candidate contributions to thesis articles* I II III IV Conceived Significant Significant Substantial Substantial the study Designed the study Substantial Substantial Substantial Substantial Collected the data NA NA Significant Substantial Analysed the data Substantial Substantial Significant Significant Manuscript preparation Substantial Substantial Substantial Substantial * Contribution Explanation.