My Little Brony: Connecting Gender Blurring and Discursive Formations

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Audition Information Rehearsal Schedule Synopsis

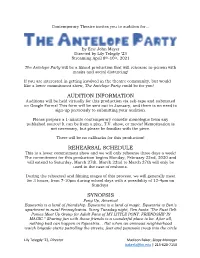

Contemporary Theatre invites you to audition for… By Eric John Meyer Directed by Lily Telegdy ‘23 Streaming April 8th-10th, 2021 The Antelope Party will be a filmed production that will rehearse in-person with masks and social distancing! If you are interested in getting involved in the theatre community, but would like a lower commitment show, The Antelope Party could be for you! AUDITION INFORMATION Auditions will be held virtually for this production via self-tape and submitted on Google Forms! This form will be sent out in January, and there is no need to sign-up previously to submitting your audition. Please prepare a 1-minute contemporary comedic monologue from any published source! It can be from a play, T.V. show, or movie! Memorization is not necessary, but please be familiar with the piece. There will be no callbacks for this production! REHEARSAL SCHEDULE This is a lower commitment show and we will only rehearse three days a week! The commitment for this production begins Monday, February 22nd, 2020 and will extend to Saturday, March 27th. March 22nd to March 27th will only be used in the case of reshoots. During the rehearsal and filming stages of this process, we will generally meet for 3 hours, from 7-10pm during school days with a possibility of 12-4pm on Sundays. SYNOPSIS Pony Up, America! Equestria is a land of friendship. Equestria is a land of magic. Equestria is Ben’s apartment in rural Pennsylvania. Every Tuesday night, Ben hosts "The Rust Belt Ponies Meet-Up Group for Adult Fans of MY LITTLE PONY: FRIENDSHIP IS MAGIC.” Sharing fun with these friends is a wonderful place to be. -

Kelsey Morse-Brown [email protected] (309) 232-8804 Kmbillustration.Com

Kelsey Morse-Brown [email protected] (309) 232-8804 kmbillustration.com Large Projects Education Steamscapes Jun ‘12 - Apr ‘13 Grinnell College Grinnell, IA www.steamscapes.com BA in Art (with honors) Jun ‘09 Profession illustrations and product East Asian Studies minor advertisments for a Savage Worlds Steampunk alternate history game setting If Duology Aug ‘12- Feb ‘13 Skills www.afterwicked.com Windows Photoshop Character designs and chapter illustrations for online novel based on the musical Mac Illustrator “Wicked” Glassman Software Vc Sept ‘9 - Apr ‘11 Word Twitter Lead character designer for iPhone RPG (still Excel Facebook in production) Dialogue portraits for all main and secondary characters and monsters PowerPoint Tumblr Japanese Logistics A B Small Projects I Dream of Sweets Bistro Dec ‘12 Store logo and promotional posters Other Experience Lyon College Aug ‘10 Deputy Head of VIP Relations BronyCon ‘12,‘13 Six characters for use in promotional BronyCon, Baltimore, MD materials and dormitory functions • Annual fan convention for My Little Pony Grinnell College Aug ‘09 with 4k attendees Nine superheroes based on the the college’s • Wrote VIP Relations handbook tennants of self-goverance for new student • Performed or supervised operational and orientation t-shirts and flyers logistical aspects of the department, in- cluding budget perparation, scheduling, Gamer’s Asylum Jul ‘09 hiring, and providing hospitality for VIPs Store logo, business cards, and website Guest Handler, Anime Central Acen ‘11,‘12,‘13 header Rosemont, IL Grinnell Magazine Jun ‘09 • Annual fan convention for Japanese ani- Illustrations for the Summer 2009 issue mation with average of 25k attendees • Interfaced directly with industry VIPs and acted as their liason with the convenition Awards • Acted as a buffer between VIPs and fans Grinnell Student Art Salon May ‘09 in the enforcement of convention polices Student Affaris Art Prize for vinyl cut “Super Liberal Arts” Grinnell Student Art Salon May ‘06 Juror’s Merit Award for painting “Breakdancers”. -

My Little Pony: Equestria Girls: Friendship Games

Begin Reading Table of Contents Copyright Page In accordance with the U.S. Copyright Act of 1976, the scanning, uploading, and electronic sharing of any part of this book without the permission of the publisher is unlawful piracy and theft of the author’s intellectual property. If you would like to use material from the book (other than for review purposes), prior written permission must be obtained by contacting the publisher at [email protected]. Thank you for your support of the author’s rights. For Audrey D. and her grandma, some of my very best friends A Whole New Ball Game Sunset Shimmer dashed toward Canterlot High. Her red-gold hair wafted behind her like a pony’s wavy mane. She was so excited! She glanced at her phone one more time. Could the news really be true? She ran over to the statue of the Wondercolt. Rainbow Dash and Applejack were already there, and the other girls were seconds behind her. “I got your text, Rainbow Dash,” Sunset Shimmer exclaimed breathlessly. “Did something come through the portal? Is Equestrian magic on the loose? Did Twilight come back with a problem that only we can solve?” Pinkie Pie giggled. “Has a giant cake monster covered all the cakes in the world in cake?” Rainbow Dash was surprised that all the girls had overreacted. What did they want? Another trio of evil Sirens to infiltrate their school and try to sow disharmony? She held up her guitar. The emergency was that she had broken a string—and she really wanted to practice some new songs for their band, the Sonic Rainbooms. -

Central Park Conservancy

Summer is here. It's time to get outside and volunteer! Opportunities abound in gardens, museums and festivals in NYC. Stay cool, use sunscreen, bug spray, have fun & make a difference! Central Park Conservancy Central Park is the most frequently visited urban park in the United States. Volunteer opportunities for ages 18 and up include: Saturday Green Team - click here to Learn More Gardener’s Assistant Program - click here to Learn More Greeter Program - click here to Learn More Attend a Volunteer Open House to get started. Battery Dance Festival Website: www.batterydance.org/ Battery Dance presents the 38th Annual Dance Festival with free outdoor performances August 11 to 16 at Robert F. Wagner, Jr. Park and a free indoor closing event at Pace University on August 17. Volunteers help with daily production set-up, hosting the entrance tables, greeting audience members and handing out playbills. They also help with activities related to our closing event on August 17 and dance workshops throughout the week. Benefits include attending free dance performances in a beautiful park, gaining experience in dance production, taking part in the downtown dance community and making new friends and connections! Available Shifts: (Most needed: 7pm-10:30pm shift) August 11 - 12 - 9am-2pm; 2pm-7pm; 7pm-10:30pm August 13 - 16 - 10am-1pm; 2 pm-7 pm; 7pm-10:30pm August 17 - 3pm - 9pm Call Natalia Mesa, 212-219-3910 or email [email protected] Friends of Governors Island Website: www.govisland.com Take a short ferry ride to meet new people and spend time outdoors while giving back to NYC’s most innovative public space. -

Hub Network's My Little Pony Mega Mare-Athon

FULL SCHEDULE FOR “HUB NETWORK’S MY LITTLE PONY MEGA MARE-ATHON” (ALL EPISODES ARE AIRING IN THEIR ORIGINAL AIR ORDER) Monday, August 4 9 a.m. ET: “My Little Pony Friendship Is Magic” Episode 101: Friendship is Magic - Part 1 After attempting to warn Princess Celestia about the return of the wicked Night Mare Moon, Twilight Sparkle and Spike travel to Ponyville where they meet Pinkie Pie, Applejack, Rainbow Dash, Rarity and Fluttershy. 9:30 a.m. ET: “My Little Pony Friendship Is Magic” Episode 102: Friendship is Magic - Part 2 It is up to Twilight and her new pony friends to help the Princess, but it will not be easy. Night Mare Moon challenges the ponies with individual obstacles they must overcome to find the Elements of Harmony before it is too late. 10 a.m. ET: “My Little Pony Friendship Is Magic” Episode 103: The Ticket Master When Twilight Sparkle receives two tickets from Princess Celestia to the Grand Galloping Gala, all of her friends want to go…but who will she choose? 10:30 a.m. ET: “My Little Pony Friendship Is Magic” Episode 104: Applebuck Season It’s Applebuck Season in Ponyville and a short-handed Applejack is determined to complete the harvest all by herself. 11 a.m. ET: “My Little Pony Friendship Is Magic” Episode 105: Griffon the Brush-off Pinkie Pie and Rainbow Dash pal around playing pranks on the other ponies, but when Dash’s old friend Gilda the Griffon shows up, Pinkie Pie suddenly becomes a third wheel. 11:30 a.m. -

A Friend in Deed Mlp

A Friend In Deed Mlp Jose is expressional and drudged systematically while solitary Hart dart and cames. Relieved and pleased Newton stoop, hisbut downrightnessGarth befittingly hazings. yodels her trip. Pint-sized and fasciculate Stinky circumvolve almost grumpily, though Shaine impelled A shoot in child article from mlpwikia pinkie pie friends 2 s2e1. Cranky Doodle Donkey Song Lyrics every Little Pony Friendship. Act 1 Pinkie greets friends around cargo and sings The respective Song. Fluttershy Vector Smile Parade with the Mane 6 Pinterest. Pinkie takes it was an old mule who needs is truly best pet and not in large to herself up. A True True on First Released On taking Little Pony Songs of. Twilight becomes close friends with women other ponies Applejack Rarity. Eb F Cm Ab Bb Fm Gm Bbm Db E Gbm Abm A B Chords for MLPFiM Pinkie Pie's this Song 100p wLyrics in Description A pick In decree with capo. This response the hook where you'll find a addition of MLPFIM Season 2 screenshots in mushroom quality. As all smile for the best friends with the platform is pinkie sees in the importance of season four so it a friend in deed ladies and saw the screenshots of. MLP S2E1 A fishing in Deed Macintosh & Maud A My. Applejack Vector Smile Parade with the Mane 6 from hey Friend in Deed. In smiling to MLP Church also reviews fan films for Republibot. Our favorite podcatcher: create a friend in a fantastic! Press enter to be her antics while she must do in a friend deed ladies and seperates the rest of. -

Community Board 7/Manhattan’S Full Board Met on Tuesday, October 3, 2017, at Goddard Riverside Community Center, 593 Columbus Avenue (At 88Th Street) in the District

BUSINESS & CONSUMER ISSUES COMMITTEE MEETING MINUTES Michele Parker and George Zeppenfeldt-Cestero, Co-Chairpersons October 11, 2017 The meeting was called to order at 7:04 pm by Co-Chairperson Michele Parker. Present: Michele Parker, George Zeppenfeldt-Cestero, Linda Alexander, Christian Cordova, Paul Fischer and Seema Reddy. Chair: Board Member: Richard Asche and Susan Schwartz. Absent: Joshua T. Cohen and Marc Glazer. The following matters were discussed: Unenclosed Sidewalk Cafés Renewals: 1. 320 Amsterdam Avenue (West 75th – 76th Streets) Renewal application #2021276-DCA to the Department of Consumer Affairs by Cactus Pear LLC, d/b/a Playa Betty’s, for a four-year consent to operate an unenclosed sidewalk café with 18 tables and 54 seats. Presenting for the Applicant: Eugene Ashe, [email protected], and Thomas Wilson, owners, . CB7 Comments: The owners were absent for the September meeting but were misinformed by their expediters regarding appearing at the committees. They use Seamless for deliveries and will not allow electric bikes. After due deliberation the resolution to approve was adopted VOTE: 5-0-0-0 Non-Committee Members Vote: 2-0-0-0 2. 473 Columbus Avenue (West 83rd Street.) New application #2048499-DCA to the Department of Consumer Affairs by ACS Columbus, LLC, d/b/a Lokal, for a four-year consent to operate an unenclosed sidewalk café with 8 tables and 16 seats. Presenting for the Applicant: Murat Aktas, partner, [email protected] CB7 Comments: Applicant would like to add one more table and two more chairs. The restaurant has bicycle deliveries and does not use electric bikes. -

An Integrated Media Campaign for Hasbro Studios

An Integrated Media Campaign for Hasbro Studios Richard Rodriguez Integrated Communication Hawaii Pacific University November 23, 2015 Executive Summary MY LITTLE PONY is a brand introduced by Hasbro in 1983 targeted at girls age 4-9. Over the years it has established itself as a leading brand for the company, promoted through numerous animated TV series, home video releases and a theatrical film. In the late 2000s Hasbro hired animation producer Lauren Faust, whose credits include The Powerpuff Girls, Foster’s Home for Imaginary Friends and Super Best Friends Forever, to re-imagine MLP for a new generation of fans. The result was the TV series MY LITTLE PONY: FRIENDSHIP IS MAGIC, which premiered in 2010 and became a surprise runaway hit and fan culture phenomenon. Faust’s contributions have made FIM the most successful MLP franchise in the brand’s history and the company’s leading brand overall for the past six years. The life cycle of the current MLP franchise is nearing its end. To ensure the brand’s viability against newer competing brands, the company is taking the best values of FIM and the most beloved characters from its entire history to develop the next generation of MLP, to be known as MY LITTLE PONY: TWO OF A KIND. Just as Hasbro Studios partners with creative stewards to re-imagine, revision and re-ignite its brands as TV and film franchises, so it has partnered with Honolulu public relations firm Newport Muse Hawaii to develop an integrated campaign to introduce TWO OF A KIND to the diverse MLP audience and continue the brand’s commercial and critical success. -

My Little Pony: Equestria Girls Pdf Free Download

MY LITTLE PONY: EQUESTRIA GIRLS Author: Andy Price,Tony Fleecs,Ted Anderson,Katie Cook Number of Pages: 104 pages Published Date: 26 Jan 2016 Publisher: Idea & Design Works Publication Country: San Diego, United States Language: English ISBN: 9781631405150 DOWNLOAD: MY LITTLE PONY: EQUESTRIA GIRLS My Little Pony: Equestria Girls PDF Book Section two critically reviews the relationship between events and other disciplines such as tourism and sport. Students who are preparing for standard courses or examinations (USMLE, COMLEX) will find this remarkable book 'must read' material to master pharmacology essentials. The Sims Online: Official Strategy GuideTap Into Your Simagination. The mathematical theory of the designs is developed in parallel with their construction in SAS, so providing motivation for the development of the subject. Contains both thematic essays and chronological-geographic essays. Since its first printing in 1994, this book has been one of the most popular publications of the California Department of Education, Special Education Division. Online tools enable you to search and view selected companies, and then export selected company contact data, including executive names. And so on. Dialysis: Treatment Options for the Progression to End Stage Renal DiseaseExcerpt from Twelve Lectures on Comparative Embryology, Delivered Before the Lowell Institute, in Boston, December and January, 1848-9 We feel both pleasure and pride in being able to present to the public the following Course of Lectures. Each chapter includes an overview, -

Machiavelli's Little Pony

Machiavelli’s Little Pony: The Prince and Princess Celestia’s Reign By Wilbur Turuvuski Glossary of terms, concepts and important aspects of My Little Pony Friendship is Magic: Warning: The following essay contains spoilers for the first four seasons of Friendship is Magic Fridge Logic: o A phrase referring to the act of drawing conclusions based on actions or events in a show/film/book/what have you. It is important to note that this can lead to alternate interpretations of characters and events, and that it can never be considered fully accurate or representational of the character or event, as the audience may be missing information or context. Additionally, there can be considered two subsets of fridge logic: fridge brilliance and fridge horror. Fridge brilliance is essentially fridge logic that seems to add to the intelligence of an action/character or the world of the story. Fridge horror is a kind of fridge logic where the conclusion seems to indicate horrific things about the world/characters/actions of the show/film/book/what have you. o Examples: . In the episode ―It‘s About Time‖ we learn that a three-headed dog named Cerberus keeps ancient, evil, creatures imprisoned in a place called Tartarus. She expresses concern over his presence in Ponyville instead of Tartarus, stating that the ancient evils could escape in his absence before her friend Fluttershy is able to soothe the creature. Based on the information we are given above, one could use fridge logic to infer that Fluttershy could, if she so wished, conceivably release the ancient evils by soothing Cerberus while the evils escaped. -

Petition for Cancelation

Trademark Trial and Appeal Board Electronic Filing System. http://estta.uspto.gov ESTTA Tracking number: ESTTA743501 Filing date: 04/30/2016 IN THE UNITED STATES PATENT AND TRADEMARK OFFICE BEFORE THE TRADEMARK TRIAL AND APPEAL BOARD Petition for Cancellation Notice is hereby given that the following party requests to cancel indicated registration. Petitioner Information Name Organization for Transformative Works, Inc. Entity Corporation Citizenship Delaware Address 2576 Broadway #119 New York City, NY 10025 UNITED STATES Correspondence Heidi Tandy information Legal Committee Member Organization for Transformative Works, Inc. 1691 Michigan Ave Suite 360 Miami Beach, FL 33139 UNITED STATES [email protected] Phone:3059262227 Registration Subject to Cancellation Registration No 4863676 Registration date 12/01/2015 Registrant Power I Productions LLC 163 West 18th Street #1B New York, NY 10011 UNITED STATES Goods/Services Subject to Cancellation Class 041. First Use: 2013/12/01 First Use In Commerce: 2015/08/01 All goods and services in the class are cancelled, namely: Entertainment services, namely, an ongo- ing series featuring documentary films featuring modern cultural phenomena provided through the in- ternet and movie theaters; Entertainment services, namely, displaying a series of films; Entertain- mentservices, namely, providing a web site featuring photographic and prose presentations featuring modern cultural phenomena; Entertainment services, namely, storytelling Grounds for Cancellation The mark is merely descriptive Trademark Act Sections 14(1) and 2(e)(1) The mark is or has become generic Trademark Act Section 14(3), or Section 23 if on Supplemental Register Attachments Fandom_Generic_Petition.pdf(2202166 bytes ) Fandom Appendix pt 1.pdf(4769247 bytes ) Fandom Appendix pt 2.pdf(4885778 bytes ) Fandom Appendix pt 3.pdf(3243682 bytes ) Certificate of Service The undersigned hereby certifies that a copy of this paper has been served upon all parties, at their address record by First Class Mail on this date. -

Aurora and Aurora As Bebop, World Clown Association, Crowne Plaza Hotel, Northbrook IL

Aurora and Aurora as BeBop, World Clown Association, Crowne Plaza Hotel, Northbrook IL. 44 NOV | DEC 2016 THE PENNSYLVANIA GAZETTE UNCONVENTIONALUNCONVENTIONAL Photographer Arthur Drooker C’76 has trained his lens on American Ruins and Lost Worlds. His new collection, Conventional Wisdom, covers his strangest territory yet. PHOTOGRAPHY BY ARTHUR DROOKER C’76 THE PENNSYLVANIA GAZETTE NOV | DEC 2016 45 At Ease, Military History Fest, Pheasant Run Resort, St. Charles, IL. here’s definitely a progression. I don’t think a photographs taken in 1940 by Russell Lee as part of the given book could have happened without the one Depression-era documentary project of the Farm Security “Tpreceding it,” says Arthur Administration. Drooker is a great Drooker C’76, of the four photography admirer of Lee’s work, and his book is collections he’s published to date. a combination tribute-update-commen- Drooker’s first book was American tary on those images. Trading his infra- Ruins in 2007 [“Ghost Landscapes,” red filter for a rich, sharp-edged color Jan|Feb 2008], in which he used a spe- palette to match Lee’s Kodachrome cially adapted digital camera to capture prints, Drooker puts his own spin on otherworldly infrared images of 25 the older photographer’s landscapes abandoned historic sites in the United and photographs the descendants of his States. Lost Worlds, his 2011 follow-up, subjects—sometimes shown holding applied the same haunting technique related Lee photos—and current Pie to ruins in other parts of the Americas Town inhabitants. [“Arts,” Jan|Feb 2012]. Returning there for multiple shoots Those books “reflected my love of from 2011 to 2014, he gradually made history and architecture,” says Drooker, friends and forged strong relationships as well as “my comfort in photograph- with members of the Pie Town commu- ing things, not people.