New Normal in China's Fdi

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

China's Belt-Road Initiative As the Signature of President Xi Jinping

Journal of Contemporary China ISSN: 1067-0564 (Print) 1469-9400 (Online) Journal homepage: https://www.tandfonline.com/loi/cjcc20 China’s Belt-Road Initiative as the Signature of President Xi Jinping Diplomacy: Easier Said than Done Suisheng Zhao To cite this article: Suisheng Zhao (2020) China’s Belt-Road Initiative as the Signature of President Xi Jinping Diplomacy: Easier Said than Done, Journal of Contemporary China, 29:123, 319-335, DOI: 10.1080/10670564.2019.1645483 To link to this article: https://doi.org/10.1080/10670564.2019.1645483 Published online: 26 Jul 2019. Submit your article to this journal Article views: 700 View related articles View Crossmark data Citing articles: 1 View citing articles Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at https://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=cjcc20 JOURNAL OF CONTEMPORARY CHINA 2020, VOL. 29, NO. 123, 319–335 https://doi.org/10.1080/10670564.2019.1645483 China’s Belt-Road Initiative as the Signature of President Xi Jinping Diplomacy: Easier Said than Done Suisheng Zhao University of Denver, USA ABSTRACT This article examines the design, objectives, and implementation of the Belt Road Initiative (BRI) six years after its inception. It argues that although the BRI as a top-level design on which President Xi has staked his personal legacy is to serve China’s ambitious geostrategic and geo- economic interests, many developing countries have welcomed the BRI because of their desperate need in infrastructure construction. But the BRI’s popularity has exceeded the substance as China has yet to bridge many fault lines on the ground. -

*All Views Expressed in Written and Delivered Testimony Are Those of the Author Alone and Not of the U.S

February 20, 2020 Isaac B. Kardon, Ph.D. – Assistant Professor, U.S. Naval War College, China Maritime Studies Institute* Testimony before the U.S.-China Economic and Security Review Commission Hearing: China’s Military Power Projection and U.S. National Interests Panel II: China’s Development of Expeditionary Capabilities: “Bases and Access Points” 1. Where and how is China securing bases and other access points to preposition materiel and facilitate its expeditionary capabilities? Previous testimony has addressed the various military logistics vessels and transport aircraft that supply People’s Liberation Army (PLA) forces operating abroad. This method is costly, inefficient, and provides insufficient capacity to sustain longer and more complex military activities beyond the range of mainland logistics networks. Yet, with the notable exception of the sole military “support base” (baozhang jidi, 保障基地)1 in Djibouti, these platforms are the PLA’s only organic mode of “strategic delivery” (zhanlüe tousong, 战略投送) to project military power overseas. Lacking a network of overseas bases in the short to medium term, the PLA must rely on a variety of commercial access points in order to operate beyond the first island chain. Because the PLA Navy (PLAN) is the service branch to which virtually all of these missions fall, this testimony focuses on port facilities. The PLAN depends on commercial ports to support its growing operations overseas. Over the course of deploying 34 escort task forces (ETF) since 2008 to perform an anti-piracy mission in the Gulf of Aden, the PLAN has developed a pattern of procuring commercial husbanding services for fuel and supplies at hundreds of ports across the globe. -

The United States, American Exceptionalism, and UNCLOS: Paradox in the Persian Gulf, Patterns in the Pacific, and the Polar Vortex

M.K. Adamowsky 2019 The Fletcher School Tufts University The United States, American Exceptionalism, and UNCLOS: Paradox in the Persian Gulf, Patterns in the Pacific, and the Polar Vortex Master of Arts in Law and Diplomacy Submitted by M.K. Adamowsky Capstone Advisor Professor Rockford Weitz In fulfillment of the MALD Capstone Requirement August 12th, 2019* *Some minor edits by the author were made in November 2019, in preparation for internet publication. 1 M.K. Adamowsky 2019 All of them, all except Phineas, constructed at infinite cost to themselves these Maginot Lines against this enemy they thought they saw across the frontier, this enemy who never attacked that way – if he ever attacked at all; if he was indeed the enemy. – John Knowles, A Separate Peace (1959) Paradoxically, a chief source of insecurity in Europe since medieval times has been this false belief that security was scarce. This belief was a self-fulfilling prophecy, fostering bellicose policies that left all states less secure. Modern great powers have been overrun by unprovoked aggressors only twice, but they have been overrun by provoked aggressors six times – usually by aggressors provoked by the victim’s fantasy-driven defensive bellicosity. Wilhelmine and Nazi Germany, Imperial Japan, Napoleonic France, and Austria-Hungary were all destroyed by dangers that they created by their efforts to escape from exaggerated or imaginary threats to their safety… – Stephen Van Evera, “Offense, Defense, and the Causes of War” (1998) If actors believe that war is imminent when it is not in fact certain to occur, the switch to implemental mind-sets can be a causal factor in the outbreak of war, by raising the perceived probability of military victory and encouraging hawkish and provocative policies. -

The Melaka Gateway Project: High Expectations but Lost Momentum?

ISSUE: 2019 No. 78 ISSN 2335-6677 RESEARCHERS AT ISEAS – YUSOF ISHAK INSTITUTE ANALYSE CURRENT EVENTS Singapore | 30 September 2019 The Melaka Gateway Project: High Expectations but Lost Momentum? Francis E. Hutchinson* EXECUTIVE SUMMARY • The Melaka Gateway Project is an ambitious maritime initiative comprising a range of port facilities, specialized economic parks, and tourist attractions. • Launched in 2014, and promoted by the Melaka-based property developer and contractor, KAJ Development Berhad, the project secured the backing of the Najib Razak administration, as well as the buy-in of powerful China-based state-owned enterprises, including Power China International. • Looking at the Gateway’s location, potential articulation with other transport projects such as the East Coast Rail Link, and the involvement of the Chinese companies, analysts have portrayed this project as a game-changer that can allow China to acquire a strategic foothold in the region. • Yet, five years after its launch, construction on the Gateway has fallen far behind schedule. • Upon closer examination, the project raises a number of questions, including whether its location is all that strategic, whether its local partners are well- connected enough to acquire the necessary capital, and, indeed, if Malaysia needs another port at this point in time. * Francis E. Hutchinson is Senior Fellow and Coordinator of the Malaysia Studies Programme at ISEAS – Yusof Ishak Institute. 1 ISSUE: 2019 No. 78 ISSN 2335-6677 INTRODUCTION The Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) launched by Chinese President Xi Jinping in 2013 aims to connect China with Europe and beyond through the construction of transportation, telecommunication, and energy networks. -

The Globalization Strategy of China —Outcomes, Challenges, and Opportunities of The“Belt and Road”Initiative—

Mitsui & Co. Global Strategic Studies Institute Monthly Report July 2017 THE GLOBALIZATION STRATEGY OF CHINA —OUTCOMES, CHALLENGES, AND OPPORTUNITIES OF THE“BELT AND ROAD”INITIATIVE— Hideaki Kishida Economic Studies Dept., Mitsui & Co., Ltd. Beijing Office “The world has never been more eager to approach China.” This is an excerpt from a video clip that the Xinhua News Agency released prior to the Belt and Road Forum for International Cooperation (BRF), which was held in Beijing from May 14-15, 2017.(1) The summit drew 29 heads of states—more than APEC and G20 did—along with government officials and representatives from several tens of countries, including Japan and the US (Fig. 1). They issued a joint communique pledging to promote the development of the Belt and Road on May 15, and also announced a second forum in 2019. Fig. 1 Main Summit Attendees and Belt and Road Projects Countries that sent heads of state to the summit G20 member countries that sent government delegates (other than countries that sent heads of state to the summit) ①-⑩: Main Belt and Road projects financed and participated in by China ① Construction of nuclear power plants at 3 sites in the UK, including Bradwell B nuclear power station that is set to implement China-made nuclear power reactor China Dragon 1st. ② Serbian Railways in Hungary ③ Development of Piraeus Port in Greece ④ Ethio-Djibouti Railways (in operation) ⑤ Kenyan railway upgraded (Mombasa- Nairobi) (in operation) ⑥ Pakistan: Gwadar Port development ⑦ Development of Colombo South Harbour and Port of Hambantota in Sri Lanka: ⑧ Development of Kyaukpyu Port in Myanmar ⑨ Development of Kuantan Port and Melaka Gateway in Malaysia ⑩ High-speed rail in Indonesia (Jakarta-Bandung) Source: Compiled by MGSSI based on the Summit ’ s joint communique, various government/embassy websites, and media reports 1 Mitsui & Co. -

World Bank Document

Sustainability Outlook EDITION CONFERENCE Diagnostic SUPPORTING REPORT 5 Public Disclosure Authorized MELAKA Shifting Melaka’s Mobility Modal Split Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized © 2019 International Bank for Reconstruction and Development / The World Bank 1818 H Street NW Washington DC 20433 Telephone: 202-473-1000 Internet: www.worldbank.org This work is a product of the staff of The World Bank with external contributions. The findings, interpretations, and conclusions expressed in this work do not necessarily reflect the views of The World Bank, its Board of Executive Directors, or the governments they represent. The World Bank does not guarantee the accuracy of the data included in this work. The boundaries, colors, denominations, and other information shown on any map in this work do not imply any judgment on the part of The World Bank concerning the legal status of any territory or the endorsement or acceptance of such boundaries. Rights and Permissions The material in this work is subject to copyright. Because The World Bank encourages dissemination of its knowledge, this work may be reproduced, in whole or in part, for noncommercial purposes as long as full attribution to this work is given. Any queries on rights and licenses, including subsidiary rights, should be addressed to World Bank Publications, The World Bank Group, 1818 H Street NW, Washington, DC 20433, USA; fax: 202-522-2625; e-mail: [email protected]. Citation Please cite the report as follows: Global Platform for Sustainable Cities, World Bank. 2019. Melaka Sustainability Outlook Diagnostic: Supporting Report 5: Shifting Melaka’s Mobility Modal Split. -

Melaka Gateway Port: an Analysis

http://www.maritimeindia.org/ Melaka Gateway Port: An Analysis Author: Anjelina Patrick* Date: 11 October 2017 Introduction This issue brief aims at analysing China’s geo-economics and geostrategic intentions as manifested in its generous assistance to Malaysia for development of the Melaka port project. The issue brief also intends to study the impact of this project upon another key player within the area, namely, Singapore, especially since the Melaka port project will, by design impact Singapore’s established position as the pre-eminent maritime hub in the Southeast Asia in general and the Malacca Strait in particular. Map.1: Geographical location of Melaka Gateway Project/ Source: Author The Melaka port project is a subset of the Melaka Gateway Project. It is a mixed development project set in Malaysia, within the strategically important Strait of Malacca. The project seeks to develop a consolidated port covering 1,366 acres of land, 2 by linking three artificial islands and one natural island. Once complete, it will include a deep sea port as well as commercial and residential property expansions. While the entire project is targeted for completion by 2025, the port per se is due to be operational by 2019, and is expected to overtake Singapore as Southeast Asia’s main shipping hub. The Project The Melaka Gateway Project was officially launched by the Prime Minister of Malaysia, Najib Razak, on 7 February 2014, as a national venture that was a part of the larger Economic Transformation Programme (ETP) by the Government of Malaysia. This strategically important project will be anchored upon the natural island of Pulau Panjang, which has a deep sea port facility with a depth of 25–30 meters. -

Multi-Modality at Tourism Destination: an Overview of the Transportation

1121 Int. J Sup. Chain. Mgt Vol. 8, No. 6, December, 2019 Multi-Modality at Tourism Destination: An Overview of the Transportation Network at the UNESCO Heritage Site Melaka, Malaysia Ahmad Sahir Jais#1, Azizan Marzuki#2 # School of Housing, Building and Planning, Universiti Sains Malaysia, 11800 Minden, Pulau Pinang, Malaysia [email protected] [email protected] Abstract— Antecedents of a tourism destination’s of road congestion, insufficient of public transport, sustainability and competitiveness rely on its dissatisfaction with the transportation network, rapid transportation networks to facilitate the movement of development of urban and suburban areas, which traffic for locals and tourist alike. Multi-modality is hamper movement and disrupt the flow of mobility. vital to support the local economies, which garner its This matter has been made worse with an ever- revenue from tourism activities. Modality plays a vital increasing number of privately owned motor vehicle, role to facilitate the mobility of tourists, inter destinations and within the destinations and relates to to the extent where an urgent solution needs to be the accessibility aspects at a tourism destination. An formulated and exercised urgently. For tourism observational study, paired with a comprehensive destinations, transportation plays a crucial role. It is analysis of literature, is conducted to explore the gamut said that, without transportation, there would not be a of the transportation networks in Melaka and its tourism industry [4], [5]. Transport is an integral part relation and contribution to the tourism industry. of tourism, which facilitates the movement of Findings show that Melaka’s tourism industry is holidaymaker, business travellers, those visiting dependent on transportation networks. -

The 21St Century Maritime Silk Road: Security

THE 21ST CENTURY MARITIME SILK ROAD Security implications and ways forward for the European Union richard ghiasy, fei su and lora saalman THE 21ST CENTURY MARITIME SILK ROAD Security implications and ways forward for the European Union richard ghiasy, fei su and lora saalman STOCKHOLM INTERNATIONAL PEACE RESEARCH INSTITUTE SIPRI is an independent international institute dedicated to research into conflict, armaments, arms control and disarmament. Established in 1966, SIPRI provides data, analysis and recommendations, based on open sources, to policymakers, researchers, media and the interested public. The Governing Board is not responsible for the views expressed in the publications of the Institute. GOVERNING BOARD Ambassador Jan Eliasson, Chair (Sweden) Dr Dewi Fortuna Anwar (Indonesia) Dr Vladimir Baranovsky (Russia) Ambassador Lakhdar Brahimi (Algeria) Espen Barth Eide (Norway) Dr Radha Kumar (India) Dr Jessica Tuchman Mathews (United States) DIRECTOR Dan Smith (United Kingdom) Signalistgatan 9 SE-169 72 Solna, Sweden Telephone: +46 8 655 97 00 Email: [email protected] Internet: www.sipri.org © SIPRI 2018 Contents Acknowledgements v Key findings and recommendations vii 1. The Maritime Silk Road 1 1.1. Scope and strategic evolution 1 1.2. Exploring China’s aspirations 4 2. The Maritime Silk Road: Security implications 11 2.1. Security implications for the South China Sea 11 2.2. Security Implications for the Indian Ocean Region 22 3. The Maritime Silk Road: Prospects for European Union security cooperation 33 3.1. Compatibility with European Union maritime security interests 33 3.2. Ways forward for the European Union 45 Annex I. Abbreviations 50 List of figures Figure 2.1. -

Consulate General of Malaysia Guangzhou, China

CONSULATE GENERAL OF MALAYSIA GUANGZHOU, CHINA e-News Letter Vol.1/ 2016 VISIT TO MALAYSIAN AND TAIWANESE OWNED COMPANIES IN DONGGUAN AND GUANGZHOU FROM 13-14 JANUARY 2016 As part of the Consulate General’s effort to strengthen rapport and better understand operations of Malaysian owned companies in Guangdong, Mr. Muzambli Markam, the Consul General of Malaysia in Guangzhou accompanied by Mr. Ruzlisham Mat Diah, Consul (Investment) and Mr. Suresh Kumar, Consul (Trade) undertook visits to several companies located in Dongguan and Guangzhou from 13-14 January 2016. Also present during the visits were Mr. Michael Tay, Consul (Tourism), Mr. Abdul Razak Junaidi, Consul (Immigration) and Mr. E Kim Tien, Consul (Information). The Malaysian delegation was briefed on the facilities and operations of the respective companies which among them include Li Yin Technology (Taiwanese company with Malaysian employee), Dongguan Shan Li Paper Co. Ltd., Musang King Outlet, Uchi Technology and Jomani Design all based in Dongguan. The Consul General and delegation also visited Sin Yan Co. Ltd., a producer of Malaysian Bird’s Nest products in Guangzhou as part of the tour. The visit presented an excellent opportunity for the Consul General and the accompanying officials to better understand the business models of the relevant companies while at the same time providing an insight to the business environment in China as a whole, Guangdong in particular. VISIT TO VS INDUSTRY GROUP LTD. IN ZHUHAI, GUANGDONG ON 26 JANUARY 2016 On 26 January 2016, Mr. Muzambli Markam, the Consul General of Malaysia in Guangzhou accompanied by Mr. Abdul Razak Junaidi, Consul (Immigration), Mr. -

10 Years Into the Inscription of Melaka & George Town As World Heritage Sites

99L Jalan Tandok, Bangsar Kuala Lumpur Phone: +603 2202 2866 E-Mail: [email protected] | Web: www.icomos-malaysia.org July 2018 ICOMOS Malaysia World Heritage Day Open Debate 2018 10 Years into the Inscription of Melaka & George Town as World Heritage Sites: The Good, The Bad & The Unintended Rapporteur’s Report ICOMOS MALAYSIA July 2018 10 Years into the Inscription of Melaka & George Town as World Heritage Sites: The Good, The Bad & The Unintended This report is based on an audio recording transcription of the ICOMOS Malaysia World Heritage Day Open Debate 2018 held at Badan Warisan Malaysia, 2 Jalan Stonor, Kuala Lumpur, on 28 April 2018 (Saturday), from 1400-1600 hrs. Report prepared by program rapporteur, Shaiful Idzwan Shahidan. Published by ICOMOS Malaysia. All rights reserved. 2 ICOMOS MALAYSIA July 2018 10 Years into the Inscription of Melaka & George Town as World Heritage Sites: The Good, The Bad & The Unintended ICOMOS Malaysia World Heritage Day Open Debate 2018 The Historic Cities of the Straits of Malacca, Melaka & George Town, have transformed in so many aspects since their inauguration in 2008 as a World Heritage Site (WHS). Much has been done, but in some cases, perhaps a bit much? How has the listing impact these two towns in the past decade, really? Are these cities on the right track? How has the World Heritage Status helped us? An open debate discussing the above matter was held as part of ICOMOS Malaysia’s World Heritage Day celebration on 28 April 2018 at Badan Warisan Malaysia. An appointed provocateur, Prof. -

Apr–Jun 2017 (PDF)

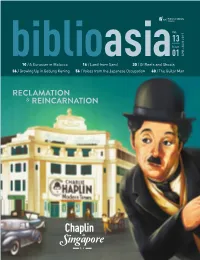

Vol. 13 Issue biblioasia01 APR–JUN 2017 10 / A Eurasian in Malacca 16 / Land from Sand 30 / Of Reefs and Shoals 36 / Growing Up in Gedung Kuning 56 / Voices from the Japanese Occupation 60 / The Guitar Man RECLAMATION & REINCARNATION Chaplin Singaporein p. 2 BiblioAsia Director’s Note Editorial & CONTENTS Vol. 13 / Issue 01 APR–JUN 2017 Production “Like everyone else I am what I am: an individual, unique and different… a history of dreams, Managing Editor desires, and of special experiences, all of which I am the sum total.” Francis Dorai So wrote Charles Spencer Chaplin (1889–1977), or Charlie Chaplin, the affable Tramp FEATURES as the world knows him, in his autobiography. The inimitable actor, producer and direc- Editor tor of the silent film era was so enamoured of the Orient that he visited Singapore three Veronica Chee Chaplin in times between 1932 and 1961. Chaplin’s visits in 1932 and 1936 are little-known trivia Singapore Editorial Support 02 that might have disappeared with the tide of time if not for Raphaël Millet’s meticulously Masamah Ahmad researched essay – a work of historical reclamation, as it were. Stephanie Pee Meeting with “Reclamation and Reincarnation” is the theme of this issue of BiblioAsia – reclamation Yong Shu Chiang in both the literal and figurative sense − as we look at historical and cultural legacies 10 the Sea Design and Print as well as human interventions that have shaped the landscape of Singapore over the Oxygen Studio Designs Pte Ltd last two centuries. Land from Sand: 10 Discover how the British, and subsequently our own government, dictated the Contributors 16 Singapore’s extent of land reclamation in Singapore through ingenious feats of civil engineering Ang Seow Leng Reclamation Story in Lim Tin Seng’s essay.