Purgatory and Penance: Differences That Remain — the Impasse Between Rome and Protestantism

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Centrality of the Holy Sacrifice of the Mass at Christendom College

THE CENTRALITY OF THE HOLY SACRIFICE OF THE MASS AT CHRISTENDOM COLLEGE The Church teaches that the Eucharist is “the source and summit of the Christian life”1 and that the celebration of the Mass “is a sacred action surpassing all others. No other action of the Church can equal its efficacy.”2 That is why “as a natural expression of the Catholic identity of the University. members of this community . will be encouraged to participate in the celebration of the sacraments, especially the Eucharist, as the most perfect act of community worship.”3 Those central truths are taught and lived at Christendom College, a “Catholic coeducational college institutionally committed to the Magisterium”4 of the Church, in the following ways: The Celebration of the Sacred Liturgy The Holy Sacrifice of the Mass • Mass is offered frequently: twice daily Monday through Thursday, three times on MONDAY (Friday), twice on Saturday, and once on Sunday (the day on which we gather as one family). • Mass in the Roman Rite is celebrated in all the ways offered by the Church: in the Ordinary Form in both English and Latin, and in the Extraordinary Form from one to three times per week, as circumstances permit. • The Ordinary Form of the Mass is celebrated with the solemnity appropriate to each feast, utilizing worthy sacred vessels and vestments, and drawing upon the Church’s rich tradition of chant, polyphony, and hymnody. • The Ordinary Form of the Mass is celebrated reverently and with rubrical fidelity. • No classes or other activities are scheduled during Mass times. • The majority of the College community attends daily Mass regularly and with great devotion. -

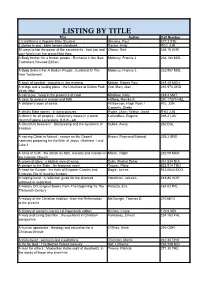

Parish Library Listing

LISTING BY TITLE Title Author Call Number 2 Corinthians (Lifeguide Bible Studies) Stevens, Paul 227.3 STE 3 stories in one : bible heroes storybook Rector, Andy REC JUN 50 ways to tap the power of the sacraments : how you and Ghezzi, Bert 234.16 GHE your family can live grace-filled lives A Body broken for a broken people : Eucharist in the New Moloney, Francis J. 234.163 MOL Testament Revised Edition A Body Broken For A Broken People : Eucharist In The Moloney, Francis J. 232.957 MOL New Testament A book of comfort : thoughts in late evening Mohan, Robert Paul 248.48 MOH A bridge and a resting place : the Ursulines at Dutton Park Ord, Mary Joan 255.974 ORD 1919-1980 A call to joy : living in the presence of God Matthew, Kelly 248.4 MAT A case for peace in reason and faith Hellwig, Monika K. 291.17873 HEL A children's book of saints Williamson, Hugh Ross / WIL JUN Connelly, Sheila A child's Bible stories : in living pictures Ryder, Lilian / Walsh, David RYD JUN A church for all peoples : missionary issues in a world LaVerdiere, Eugene 266.2 LAV church Eugene LaVerdiere, S.S.S - edi A Church to believe in : Discipleship and the dynamics of Dulles, Avery 262 DUL freedom A coming Christ in Advent : essays on the Gospel Brown, Raymond Edward 226.2 BRO narritives preparing for the Birth of Jesus : Matthew 1 and Luke 1 A crisis of truth - the attack on faith, morality and mission in Martin, Ralph 282.09 MAR the Catholic Church A crown of glory : a biblical view of aging Dulin, Rachel Zohar 261.834 DUL A danger to the State : An historical novel Trower, Philip 823.914 TRO A heart for Europe : the lives of Emporer Charles and Bogle, James 943.6044 BOG Empress Zita of Austria-Hungary A helping hand : A reflection guide for the divorced, Horstman, James L. -

The Virtue of Penance in the United States, 1955-1975

THE VIRTUE OF PENANCE IN THE UNITED STATES, 1955-1975 Dissertation Submitted to The College of Arts and Sciences of the UNIVERSITY OF DAYTON In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for The Degree Doctor of Philosophy in Theology By Maria Christina Morrow UNIVERSITY OF DAYTON Dayton, Ohio December 2013 THE VIRTUE OF PENANCE IN THE UNITED STATES, 1955-1975 Name: Morrow, Maria Christina APPROVED BY: _______________________________________ Sandra A. Yocum, Ph.D. Committee Chair _______________________________________ William L. Portier, Ph.D. Committee Member Mary Ann Spearin Chair in Catholic Theology _______________________________________ Kelly S. Johnson, Ph.D. Committee Member _______________________________________ Jana M. Bennett, Ph.D. Committee Member _______________________________________ William C. Mattison, III, Ph.D. Committee Member iii ABSTRACT THE VIRTUE OF PENANCE IN THE UNITED STATES, 1955-1975 Name: Morrow, Maria Christina University of Dayton Advisor: Dr. Sandra A. Yocum This dissertation examines the conception of sin and the practice of penance among Catholics in the United States from 1955 to 1975. It begins with a brief historical account of sin and penance in Christian history, indicating the long tradition of performing penitential acts in response to the identification of one’s self as a sinner. The dissertation then considers the Thomistic account of sin and the response of penance, which is understood both as a sacrament (which destroys the sin) and as a virtue (the acts of which constitute the matter of the sacrament but also extend to include non-sacramental acts). This serves to provide a framework for understanding the way Catholics in the United States identified sin and sought to amend for it by use of the sacrament of penance as well as non-sacramental penitential acts of the virtue of penance. -

Expiation–Propitiation–Reconciliation

Expiation–Propitiation–Reconciliation by Chrys C. Caragounis (Professor Emeritus in New Testament Exegesis at Lund University) 1. Introductory1 As is well-known, the New Testament does not present a systematic theology of the Christian Faith. Nevertheless, it supplies all the necessary ingredients toward a systematic theology. Of all the writings of the New Testament, the most systematic is the epistle to the Romans. The epistle to the Hebrews offers a more or less systematic presentation of the sacrificial system in Israel as this is fulfilled in the high priesthood of Christ, who is not only the high priest but becomes also the sacrificial victim. But the scope of this epistle is quite narrow as compared with the wide vistas that open up in the epistle to the Romans.2 This absence of a formally systematic theology in the New Testament is to be explained by what constituted the pressing needs of the young, growing Church. The epistles of Paul, for example, were written to solve practical problems that had arisen in the various congregations. And even Romans, the most systematic of all Paul’s epistles, was written as an occasional letter with practical aims in view.3 1 This study has been written in as simple and non-technical manner as was possible. However, in order to discuss the subject somewhat adequately, it was impossible to avoid some technical terminology as well as a few references to ancient and modern literature. In order not to burden the main text, such technicalities have been relegated for the most part to the footnotes. -

How Can a Just God Pardon Evil? – Romans 3:21-31

How Can a Just God Pardon Evil? – Romans 3:21-31 John Piper in his book Desiring God says that verses 25-26 may be the most important verses in the Bible. In His Solid Joys devotional he calls this the ‘Best Passage Ever’. God is both Just and ‘The Justifier’ – how can this be possible? Because of Jesus Christ, because he was put forward as a ‘propitiation by his blood’, so that He may be seen as righteous and that we too might be declared righteous. This truth, is the greatest truth! 1) What is Propitiation? “Propitiation is a sacrifice that bears God’s wrath so that God becomes ‘propitious’ or favorably disposed toward us.” - Wayne Grudem. “All have sinned and fall short of the glory of God” (Verse 23). Jesus said “No one is good except God alone” (Mark 10:18). People don’t like this statement as we want to consider ourselves good. For a person to be good or bad we need a. A standard for Good and Bad b. An assessment of someone’s goodness compared to the standard c. A judge, someone to decide whether or not they pass. Where do we get that standard from, who assesses and who gets to decide? Surely, it’s only the person who has lived a perfect life. Who has never wronged anybody, who is utterly selfless, kind and without prejudice. And that person said ‘no one is good, except God alone’. There is still hope as Paul has just stated that this justification, this being acceptable, being judged as ‘good’ comes to all who believe. -

Paradise - Purgatory - Perdition

PARADISE - PURGATORY - PERDITION A short time before the Lord Jesus Christ went to the cross of Calvary to put away sin by the sacrifice of Himself, He said, concerning His disciples: “While I was with them in the world, I kept them in Thy name: those that Thou gavest Me I have kept, and none of them is lost, but the son of PERDITION: that the Scripture might he fulfilled:” John 17:12. Judas Iscariot was “the son of perdition.” Then note II Thessalonians 2:3: “Let no man deceive you by any means; for that day shall not come, except there come a falling away first, and that man of sin be revealed, the son of PERDITION.” The coming of the “man of sin” will also be “the son of perdition.” Then note Revelation 17:8: “The beast that thou sawest was and is not; and shall ascend out of the bottom less pit, and go into PERDITION: and they that dwell on the earth shall wonder, whose names were not written in the Book of Life from the foundation of the world, when they, behold the beast that was, and is not, and yet is.” Then we read in Hebrews 10:39 and II Peter 3:7 concerning some who shall go to perdition: “But we are not of them who draw back unto PERDITION; but of them that believe to the saving of the soul.” “But the heavens and the earth which are now, by the same word are kept in store, reserved unto fire against the day of judgment and PERDITION of ungodly men.” PARADISE When the Lord Jesus was dying on the cross, a thief near by on another cross called on Him. -

Repentance, Penance, & the Forgiveness of Sins

REPENTANCE, PENANCE, & THE FORGIVENESS OF SINS Catholic translations of the Bible have often used the words “repentance” and “penance” interchangeably. Compare the Douay- Rheims Version with the New American Catholic Bible at Acts 2:38 and Acts 26:20 and you will see that these words (repentance & penance) are synonymous, words carrying the same meaning as the another. The Catholic Dictionary published by “Our Sunday Visitor”, a Catholic publication defines these words in the following ways: Repentance = Contrition for sins and the resulting embrace of Christ in conformity to Him. Penance or Penitence = Spiritual change that enables a sinner to turn away from sin. The virtue that enables human beings to acknowledge their sins with true contrition and a firm purpose of amendment. If there is any difference of meaning, I would suggest from pondering Greek definitions, that repentance (from the New Testament) 1 focuses on a change of heart, a change of mind and penance centers on the works of faith that this change of heart has produced. But both the change of heart and the works of faith go together; they are part of the same package. The Church has always taught that Christ’s death and resurrection brought reconciliation between God and humanity and that “the Lord entrusted the ministry of reconciliation to the Church.”1 The catechism teaches that because sin often wrongs the neighbor, while absolution forgives sin, “it does not remedy all the disorders sin has caused,”2 therefore the sinner must still recover his full spiritual health by doing works meet for repentance, that is, prove your repentance by what you do. -

PAUL's THEOLOGY Lesson 28 Salvation – Part 4 Metaphor – Propitiation

PAUL’S THEOLOGY Lesson 28 Salvation – Part 4 Metaphor – Propitiation One of the many people who help our class “go” is Mike Hudgins. For seven years, Mike has led the effort to make sure the sound is working each Sunday morning. Mike has worked through multiple soundboards, with different incarnations of microphones (no Mike/mic bad puns here!), and in multiple venues week in and week out to make sure these lessons are heard in class and beyond. Like so many others, Mike consistently makes personal sacrifices for our benefit. Thank you, Mike! Now when I write of Mike’s sacrifices, I need to pause for a moment. Because if you know Mike well, then you know he is a huge baseball fan. In fact, in addition to Mike’s regular job, Mike also umpires baseball games. These games are serious games, not simply the Saturday afternoon Little League fair. Mike is one of our area’s top umpires. “Sacrifice” has a special meaning to Mike. It is when a batter hits into an out to advance a runner. Today, we are studying “sacrifice.” We are not studying the kind of sacrifice that so many make in order for this class to be as effective as it is. Nor are we studying the kind of sacrifice we might see in a baseball game. We are studying a special type of sacrifice that makes our salvation before God Almighty. We are studying the blood sacrifice of Jesus Christ. As we study the sacrifice of Christ, we look specifically at a metaphor Paul uses to describe the working of our salvation: propitiation. -

Catholic Doctrine of Purgatory

Catholic Doctrine Of Purgatory Intro: Prior to making a study of this doctrine, I did not realize just how repulsive and evil the doctrine of purgatory is. After studying it, I am now convinced that there is no doctrine as immoral and ungodly as the doctrine of purgatory. It strikes at the very heart of Christianity and the sacrifice of God’s only begotten Son. I am not sure that I possess the capability of expressing the disgust which should permeate our very souls because of this ungodly doctrine and the wicked practices which arise from it. I. WHAT IS PURGATORY. A. Let them speak for themselves. 1. Catholic catechism (Catechism Of The Catholic Church (New York, NY: Doubleday, 1994), p. 291.): “1030 All who die in Gods grace and friendship, but still imperfectly purified, are indeed assured of their eternal salvation; but after death they undergo purification, so as to achieve the holiness necessary to enter the joy of heaven. 1031 The church gives the name Purgatory to this final purification of the elect, which is entirely different from the punishment of the damned. The Church formulated her doctrine of faith on Purgatory especially at the Councils of Florence and Trent. The tradition of the church, by reference to certain text of Scripture, speaks of the cleansing fire: ‘As for certain lesser faults, we must believe that, before the Final Judgment, there is a purifying fire. He who is truth says that who ever utters blasphemy against the Holy Spirit will be pardoned neither in this age or in the age to come. -

Defending Your Catholic Faith

Eastern Catholic Re-Evangelization Center The Book of Armaments ܞ Defending Your Catholic Faith by Gary Michuta CONTENTS CHAPTER ONE - SALVATION WHAT IS SALVATION AND JUSTIFICATION?.........................................................................................2 A Word of Warning...............................................................................................................2 Defining Terms: ....................................................................................................................2 Grace .....................................................................................................................................3 Faith.......................................................................................................................................3 Works ....................................................................................................................................5 -In Brief-....................................................................................................................................6 UNDERSTANDING JUSTIFICATION ........................................................................................................7 The Preparatory Stage ...........................................................................................................7 Justification Proper................................................................................................................8 After Initial Justification .......................................................................................................9 -

Propitiation & Atonement

Study Notes Propitiation & Atonement November 2, 2014 28 It shall be for Aaron and his sons as a perpetual due from the people of Israel, for it is a contribution. It shall be a contribution from the people of Israel from their peace offerings, their contribution to the LORD. 29 "The holy garments of Aaron shall be for his sons after him; they shall be anointed in them and ordained in them. 30 The son who succeeds him as priest, who comes into the tent of meeting to minister in the Holy Place, shall wear them seven days. 31 "You shall take the ram of ordination and boil its flesh in a holy place. 32 And Aaron and his sons shall eat the flesh of the ram and the bread that is in the basket in the entrance of the tent of meeting. 33 They shall eat those things with which atonement was made at their ordination and consecration, but an outsider shall not eat of them, because they are holy. 34 And if any of the flesh for the ordination or of the bread remain until the morning, then you shall burn the remainder with fire. It shall not be eaten, because it is holy. 35 "Thus you shall do to Aaron and to his sons, according to all that I have commanded you. Through seven days shall you ordain them, 36 and every day you shall offer a bull as a sin offering for atonement. Also you shall purify the altar, when you make atonement for it, and shall anoint it to consecrate it. -

(313 Duke Street) the BASILICA SCHOOL

July 4, 2021 The Fourteenth Sunday in Ordinary Time Very Rev. Edward C. Hathaway, Rector Rev. David A. Dufresne, Parochial Vicar Rev. Joseph B. Townsend, Parochial Vicar Rev. Noah C. Morey, In Residence Mr. Jordan Evans, Seminarian 310 South Royal Street + Alexandria, VA 22314 + 703.836.4100 + www.stmaryoldtown.org + [email protected] HOLY SACRIFICE OF THE MASS All Masses are live streamed at www.stmaryoldtown.org SUNDAY 7 a.m., 8:30 a.m., 10 a.m., 11:30 a.m., 1 p.m. and 5 p.m. MONDAY through FRIDAY 6:30 a.m., 8 a.m. and 12:10 p.m. SATURDAY 8:30 a.m. and 5 p.m. (Vigil for Sunday) TRADITIONAL LATIN MASS 7:30 p.m., Third Friday of the month FEDERAL HOLIDAYS and HOLY DAYS Check the website and bulletin SACRAMENT OF PENANCE MONDAY through FRIDAY After 12:10 p.m. Mass WEDNESDAY 7:30 to 8:30 p.m. SATURDAY 9 to 10 a.m. and 4 to 5 p.m. Rosary Monday through Friday before 8 a.m. Mass BASILICA HOURS and on Saturday before 8:30 a.m. Mass MONDAY through FRIDAY 5:30 a.m. to 9 p.m. Miraculous Medal Novena Monday 12 noon SATURDAY 7:30 a.m. to 6:30 p.m. Adoration of the Blessed Sacrament Wednesday 12:45 to 8:30 p.m. SUNDAY 6 a.m. to 6:30 p.m. Adoration with Holy Hour & Benediction Wednesday 7:30 to 8:30 p.m. OFFICE HOURS (313 Duke Street) First Friday Nocturnal Adoration MONDAY through FRIDAY 9 a.m.