5.Zen Is Eternal Life

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Buddhism in America

Buddhism in America The Columbia Contemporary American Religion Series Columbia Contemporary American Religion Series The United States is the birthplace of religious pluralism, and the spiritual landscape of contemporary America is as varied and complex as that of any country in the world. The books in this new series, written by leading scholars for students and general readers alike, fall into two categories: some of these well-crafted, thought-provoking portraits of the country’s major religious groups describe and explain particular religious practices and rituals, beliefs, and major challenges facing a given community today. Others explore current themes and topics in American religion that cut across denominational lines. The texts are supplemented with care- fully selected photographs and artwork, annotated bibliographies, con- cise profiles of important individuals, and chronologies of major events. — Roman Catholicism in America Islam in America . B UDDHISM in America Richard Hughes Seager C C Publishers Since New York Chichester, West Sussex Copyright © Columbia University Press All rights reserved Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Seager, Richard Hughes. Buddhism in America / Richard Hughes Seager. p. cm. — (Columbia contemporary American religion series) Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN ‒‒‒ — ISBN ‒‒‒ (pbk.) . Buddhism—United States. I. Title. II. Series. BQ.S .'—dc – Casebound editions of Columbia University Press books are printed on permanent and durable acid-free paper. -

PACIFIC WORLD Journal of the Institute of Buddhist Studies

PACIFIC WORLD Journal of the Institute of Buddhist Studies PACIFIC WORLD Journal of the Institute of Buddhist Studies Third Series Number 17 2015 Special Issue: Fiftieth Anniversary of the Bukkyō Dendō Kyōkai Pacific World is an annual journal in English devoted to the dissemination of his- torical, textual, critical, and interpretive articles on Buddhism generally and Shinshu Buddhism particularly to both academic and lay readerships. The journal is distributed free of charge. Articles for consideration by the Pacific World are welcomed and are to be submitted in English and addressed to the Editor, Pacific World, 2140 Durant Ave., Berkeley, CA 94704-1589, USA. Acknowledgment: This annual publication is made possible by the donation of BDK America of Moraga, California. Guidelines for Authors: Manuscripts (approximately twenty standard pages) should be typed double-spaced with 1-inch margins. Notes are to be endnotes with full biblio- graphic information in the note first mentioning a work, i.e., no separate bibliography. See The Chicago Manual of Style (16th edition), University of Chicago Press, §16.3 ff. Authors are responsible for the accuracy of all quotations and for supplying complete references. Please e-mail electronic version in both formatted and plain text, if possible. Manuscripts should be submitted by February 1st. Foreign words should be underlined and marked with proper diacriticals, except for the following: bodhisattva, buddha/Buddha, karma, nirvana, samsara, sangha, yoga. Romanized Chinese follows Pinyin system (except in special cases); romanized Japanese, the modified Hepburn system. Japanese/Chinese names are given surname first, omit- ting honorifics. Ideographs preferably should be restricted to notes. -

Moon by the Window

DaI Te oM B ontents BOaSK NGMK NrKeGIK H SnqqGry 8mcKx ne CGSSOMrGoNOKq ,4mMSOqNA 8mcKx ne CGSSOMrGoNOKq ,RnT GPOA Aansa E OqcnT Ns aSOIGaOnmq CnoyrOMNa NGMK Prxyatx Rxyxrxntxs to tyx moon appxar yrxquxntly zn qxn koans as a syortyanw yor tyx awakxnxw mznw. Altyouxy tyxsx tallzxrapyy pyrasxs arx not tyx moon ztsxly- tyxy offxr a mxans yor awakxnznx to tyx mznw’s wzswom sy sxrvznx as a rxmznwxr oy tyx txatyznxs wyxn a txatyxr zs not prxsxnt. Tyx tallzxrapyzxs tyxmsxlvxs provzwx an xxprxsszon oy tyx awakxnxw mznw- a vzsual Dyarma- tapturznx tyx lzvznx xnxrxy oy a momxnt zn znk on papxr. Tyus- worws anw zmaxxs work toxxtyxr to tonvxy tyx xssxntx oy qxn to tyx vzxwxr anw rxawxr. Known zntxrnatzonally as a tallzxrapyxr anw mastxr txatyxr- Syowo aarawa was sorn zn B94A zn Nara- capan. ax sxxan yzs qxn traznznx zn B9HC wyxn yx xntxrxw Syoyuku.jz monastxry zn Kosx- capan. Aytxr traznznx unwxr ramawa Mumon Rosyz ,B9AA–B988A yor twxnty yxars- yx rxtxzvxw Dyarma transmzsszon anw was appozntxw assot oy Soxxn.jz monastxry zn Okayama- capan- wyxrx yx yas tauxyt szntx B98C. aarawa Rosyz zs yxzr to tyx txatyznxs oy Rznzaz qxn Buwwyzsm as passxw wown zn capan tyrouxy Mastxr aakuzn anw yzs suttxssors. aarawa Rosyz’s txatyznx zntluwxs trawztzonal Rznzaz prattztxs znyormxw sy wxxp tompasszon anw pxrmxatxw sy tyx szmplx anw wzrxtt Mayayana wottrznx tyat all sxznxs arx xnwowxw wzty tyx tlxar- purx Orzxznal Buwwya Mznw. Protxxwznx yrom tyzs all.xmsratznx vzxw- aarawa Rosyz yas wxltomxw sxrzous stuwxnts ,womxn anw mxn- lay anw orwaznxwA yrom all ovxr tyx worlw to trazn at Soxxn.jz anw tyx txmplxs yx yas xstaslzsyxw nxar Sxattlx- oasyznxton- anw zn Gxrmany- as wxll as at morx tyan a wozxn szttznx xroups arounw tyx worlw. -

On the Penetration of Dharmakya and Dharmadesana -Based on the Different Ideas of Dharani and Tathagatagarbha

On the Penetration of Dharmakya and Dharmadesana -based on the different ideas of dharani and tathagatagarbha- Kakusho U jike We can recognize many developements of the Buddhakaya theory in the evo- lution of Mahayana thought systems which are related to various doctrines such as the Vi jnanavada, etc. In my opinion, the Buddhakaya theory stressed how the Bodhisattvas or any living being can meet the eternal Buddha and enjoy the benefits of instruction on enlightenment from him. In the Mahayana, the concept of truth also developed parallel with the Bud- dhakaya theory and the most important theme for the Mahayanist is how to understand the nature of the Buddha who became one with the truth (dharma- kaya). That is to say, the problem of how to realize the truth is the same pro- blem of how to meet the eternal Buddha with the joy of uniting oneself with the realm of the Buddha's enlightenment (dharmadhatu). In this situation one's faculties are always tested in the effort to encounter and understand the real teaching of the Buddha, because the truth revealed by the Buddha is quite high and deep, going beyond the intellect of ordinary people The Buddha's teaching is understood only by eminent Bodhisattvas who possess the super power of hearing the subtle voice of the Buddha. One of the excellent means of the Bodhisattvas for hearing, memorizing, and preaching etc., the teachings of the Buddha is considered to be the dharani. Dharani seemed to appear at first in the Prajnaparamita-sutras or in other Sutras having close relation to theme). -

The Buddhist Conception of Reality

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE The Buddhist Conception of Reality Daisetz T. Suzuki There is one question every earnest-minded man will ask as soon as he grows old, or rather, young enough to reason about things, and that is: “Why are we here?” or “What is the significance of life here?” The question may not always take this form; it will vary according to the surroundings and circum stances in which the questioner may happen to find himself. Once up to the horizon of consciousness, this question is quite a stubborn one and will not stop disturbing one’s peace of mind. It will insist on getting a satisfactory answer one way or another. This inquiry after the significance or value of life is no idle one, and no verbal quibble will gratify the inquirer for he is ready to give his life for it. We fre quently hear in Japan of young men committing suicide, despairing at their inability to solve the question. While this is a hasty and in a way cowardly deed, they are so upset that they do not know what they are doing; they are altogether beside themselves. This questioning about the significance of life is tantamount to seeking after ultimate reality. Ultimate reality may sound to some people too philosophical and they may regard it as of no concern to them. They may regard it outside their domain of interest, and the subject I am going to speak about tonight is liable to be put aside as belonging to the professional business of a class of peo ple known as philosophers. -

YOGA INFLUENCE YOGA INFLUENCE English Version of YOGAPRABHAVA Discourse by Saint Gulabrao Maharaj on ‘Patanjala Yogasutra’

YOGA INFLUENCE YOGA INFLUENCE English Version of YOGAPRABHAVA Discourse by Saint Gulabrao Maharaj on ‘Patanjala Yogasutra’ Translated By Vasant Joshi Published by Vasant Joshi YOGA INFLUENCE YOGA INFLUENCE English Version of YOGAPRABHAVA Discourse by Saint Gulabrao Maharaj on ‘Patanjala Yogasutra’ * Self Published by: Vasant Joshi English Translator: Vasant Joshi © B-8, Sarasnagar, Siddhivinayak Society, Shukrawar Peth, Pune 411021. Mobile.: +91-9422024655 | Email : [email protected] * All rights reserved with English Translator No part of this book may be reproduced or utilized in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical including photocopying recording or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the English Translator. * Typesetting and Formatting Books and Beyond Mrs Ujwala Marne New Ahire Gaon, Warje, Pune. Mobile. : +91-8805412827 / 7058084127 | Email: [email protected] * Preface by : Dr. Vijay Bhatkar, Chief Mentor, Multiversity. * Cover Design by : Aadity Ingawale * First Edition : 26th January 2021 YOGA INFLUENCE DEDICATED TO THE MEMORY OF G My Brother My Sister Late Prabhakar Joshi Late Sudha Natu yG y YOGA INFLUENCE INDEX Subject Page No. Part I Preface - Dr. Vijay Bhatkar I Prologue of English Translator - Vasant Joshi IV Acquaintance - Dr. K. M. Ghatate VI Autobiography of Saint Gulabrao Maharaj XLII Introduction - Rajeshwar Tripurwar LI Swami Bechiranand - Rajeshwar Tripurwar LVI Tribute - Vasant Joshi LIX Part II Chapter I : Introduction 4 to 37 Aphorism 1 to 22 Chapter II : God Meditation 38 to 163 Aphorism 23 to 33 Chpter III : Study 164 to 300 Aphorism 34 to 39 Chapter IV : Fruit of Yoga Study 301 to 357 Aphorism 40 to 44 Pious Behaviour Indication 358 to 362 Steps Perfection 363 to 370 Part III Appendix : Glossary of Technical Terms 373 to 395 References 396 G YOGA INFLUENCE PART I YOGA INFLUENCE INDEX Subject Page No. -

The Mind-Body in Pali Buddhism: a Philosophical Investigation

The Mind-Body Relationship In Pali Buddhism: A Philosophical Investigation By Peter Harvey http://www.buddhistinformation.com/mind.htm Abstract: The Suttas indicate physical conditions for success in meditation, and also acceptance of a not-Self tile-principle (primarily vinnana) which is (usually) dependent on the mortal physical body. In the Abhidhamma and commentaries, the physical acts on the mental through the senses and through the 'basis' for mind-organ and mind-consciousness, which came to be seen as the 'heart-basis'. Mind acts on the body through two 'intimations': fleeting modulations in the primary physical elements. Various forms of rupa are also said to originate dependent on citta and other types of rupa. Meditation makes possible the development of a 'mind-made body' and control over physical elements through psychic powers. The formless rebirths and the state of cessation are anomalous states of mind-without-body, or body-without-mind, with the latter presenting the problem of how mental phenomena can arise after being completely absent. Does this twin-category process pluralism avoid the problems of substance- dualism? The Interaction of Body and Mind in Spiritual Development In the discourses of the Buddha (Suttas), a number of passages indicate that the state of the body can have an impact on spiritual development. For example, it is said that the Buddha could only attain the meditative state of jhana once he had given up harsh asceticism and built himself up by taking sustaining food (M.I. 238ff.). Similarly, it is said that health and a good digestion are among qualities which enable a person to make speedy progress towards enlightenment (M.I. -

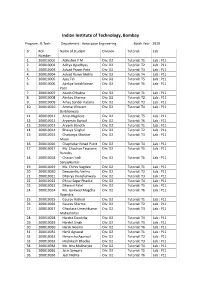

Rolllist Btech DD Bs2020batch

Indian Institute of Technology, Bombay Program : B.Tech. Department : Aerospace Engineering Batch Year : 2020 Sr. Roll Name of Student Division Tutorial Lab Number 1. 200010001 Abhishek P M Div: D2 Tutorial: T1 Lab : P11 2. 200010002 Aditya Upadhyay Div: D2 Tutorial: T2 Lab : P11 3. 200010003 Advait Pravin Pote Div: D2 Tutorial: T3 Lab : P11 4. 200010004 Advait Ranvir Mehla Div: D2 Tutorial: T4 Lab : P11 5. 200010005 Ajay Tak Div: D2 Tutorial: T5 Lab : P11 6. 200010006 Ajinkya Satishkumar Div: D2 Tutorial: T6 Lab : P11 Patil 7. 200010007 Akash Chhabra Div: D2 Tutorial: T1 Lab : P11 8. 200010008 Akshay Sharma Div: D2 Tutorial: T2 Lab : P11 9. 200010009 Amay Sunder Kataria Div: D2 Tutorial: T3 Lab : P11 10. 200010010 Ammar Khozem Div: D2 Tutorial: T4 Lab : P11 Barbhaiwala 11. 200010011 Anup Nagdeve Div: D2 Tutorial: T5 Lab : P11 12. 200010012 Aryaman Bansal Div: D2 Tutorial: T6 Lab : P11 13. 200010013 Aryank Banoth Div: D2 Tutorial: T1 Lab : P11 14. 200010014 Bhavya Singhal Div: D2 Tutorial: T2 Lab : P11 15. 200010015 Chaitanya Shankar Div: D2 Tutorial: T3 Lab : P11 Moon 16. 200010016 Chaphekar Ninad Punit Div: D2 Tutorial: T4 Lab : P11 17. 200010017 Ms. Chauhan Tejaswini Div: D2 Tutorial: T5 Lab : P11 Ramdas 18. 200010018 Chavan Yash Div: D2 Tutorial: T6 Lab : P11 Sanjaykumar 19. 200010019 Ms. Chinni Vagdevi Div: D2 Tutorial: T1 Lab : P11 20. 200010020 Deepanshu Verma Div: D2 Tutorial: T2 Lab : P11 21. 200010021 Dhairya Jhunjhunwala Div: D2 Tutorial: T3 Lab : P11 22. 200010022 Dhruv Sagar Phadke Div: D2 Tutorial: T4 Lab : P11 23. 200010023 Dhwanil Patel Div: D2 Tutorial: T5 Lab : P11 24. -

On Lay Practice Within North American Soto Zen James Ishmael Ford 5 February 2018 Blue Cliff Zen Sangha Costa Mesa, California L

On Lay Practice Within North American Soto Zen James Ishmael Ford 5 February 2018 Blue Cliff Zen Sangha Costa Mesa, California Last week I posted on my Monkey Mind blog an essay I titled Soto Zen Buddhism in North America: Some Random Notes From a Work in Progress. There I wrote, along with a couple of small digressions and additions I add for this talk: Probably the most important thing here (within our North American Zen and particularly our North American Soto Zen) has been the rise in the importance of lay practice. My sense is that the Japanese hierarchy pretty close to completely have missed this as something important. And, even within the convert Soto ordained community, a type of clericalism that is a sense that only clerical practice is important exists that has also blinded many to this reality. That reality is how Zen practice belongs to all of us, whatever our condition in life, whether ordained, or lay. Now, this clerical bias comes to us honestly enough. Zen within East Asia is project for the ordained only. But, while that is an historical fact, it is very much a problem here. Actually a profound problem here. Throughout Asia the disciplines of Zen have largely been the province of the ordained, whether traditional Vinaya monastics or Japanese and Korean non-celibate priests. This has been particularly so with Japanese Soto Zen, where the myth and history of Dharma transmission has been collapsed into the normative ordination model. Here I feel it needful to note this is not normative in any other Zen context. -

The Dogen Canon D 6 G E N ,S Fre-Shobogenzo Writings and the Question of Change in His Later Works

Japanese Journal of Religious Studies 1997 24/1-2 The Dogen Canon D 6 g e n ,s Fre-Shobogenzo Writings and the Question of Change in His Later Works Steven H eine Recent scholarship has focused on the question of whether, and to what extent, Dogen underwent a significant change in thought and attitudes in nis Later years. Two main theories have emerged which agree that there was a decisive change although they disagree about its timing and meaning. One view, which I refer to as the Decline Theory, argues that Dogen entered into a prolonged period of deterioration after he moved from Kyoto to Echizen in 1243 and became increasingly strident in his attacks on rival lineages. The second view, which I refer to as the Renewal Theory, maintains that Dogen had a spiritual rebirth after returning from a trip to Kamakura in 1248 and emphasized the priority of karmic causality. Both theories, however, tend to ignore or misrepresent the early writings and their relation to the late period. I will propose an alternative Three Periods Theory suggesting that the main change, which occurred with the opening of Daibutsu-ji/Eihei-ji in 1245, was a matter of altering the style of instruc tion rather than the content of ideology. At that point, Dogen shifted from the informal lectures (jishu) of the Shdbdgenzd,which he stopped deliver ing, to the formal sermons (jodo) in the Eihei koroku, a crucial later text which the other theories overlook. I will also point out that the diversity in literary production as well as the complexity and ambiguity of historical events makes it problematic for the Decline and Renewal theories to con struct a view that Dogen had a single, decisive break with his previous writings. -

31 Planes of Existence (1)

31 Planes of Existence (1) Kamaloka Realms Death & Rebirth All putthujjhanas are subjected to death & rebirths “Death proximate kamma” or last thoughts moment leads to the realm of rebirth. Good or bad, it tends to be the state of mind characteristic of the being in his previous life It could be hate, metta, karuna, tanha, and so on. Tanha is the one that binds us to Samsara, esp the sensual worlds Depends on 3 types of action (mental, physical & vocal manifesting in thought, action & speech) Purified consciousness leads to birth in higher planes such as Brahma lokas Mixed type will lead to birth in the intermediate planes of kama lokas Predominantly bad kamma will lead to birth in the Duggatti (unhappy states) 1 Only humans on earth? Early Buddhist texts (Nikaya), mentioned: “the thousandfold world system” “the twice thousandfold world system” “the thrice thousandfold world system” Buddhaghosa said there are 1,000,000,000,000 world systems 3 Types of Worlds Kama-loka or kamabhava (sensuous world) 11 planes Rupa-loka or rupabhava (the world of form or fine material world) 16 planes Arupa-loka or arupabhava (the formless world / immaterial world) 4 planes 2 Kama-Loka The sensuous world is divided into Kamaduggati (those states that are not desirable and unsatisfactory with unpleasant and painful feelings) Kamasugati (those states that are desirable or satisfying with pleasant and pleasurable feelings) Kamaduggati Bhumi 4 States of Suffering (Apaya) Niraya (Hell) Tiracchana Yoni (Animals) Peta Loka (Hungry ghosts) Asura (Demons) 3 Niraya (Hell) Lowest level of existence with Devoid of sukha. Only non-stop unimaginable suffering & anguish Dukha. -

To Transmit Dogen Zenji's Dharma

http://www.stanford.edu/group/scbs/Dogen/Dogen_Zen_papers/%20Otani. html [03.10.03] To Transmit Dogen Zenji's Dharma Otani Tetsuo Introduction It is my pleasure to address the distinguished guests who have gathered today at Stanford University to celebrate the 800th anniversary of the birth of Dogen Zenji. In my talk today, I will discuss the topic of "Dharma transmission," first by reflecting on Dogen Zenji's interpretation of the idea. Second, I will examine the so-called "lineage- restoration" movement (shuto fukko) of the early modern period which had the issue of Dharma transmission at its core. And finally, I will conclude with a reflection on the significance of receiving and transmitting the Dharma today. I. Dogen Zenji's Dharma Transmission and Buddha Dharma While practicing in the assembly of Musai Ryoha at Tendozan Monastery right after he went to China at the age of 24, Dogen initially had an interest in the genealogy document (shisho), a certificate authenticating the transmission of the Dharma. Dogen was clearly moved when he actually had opportunities to see "transmission documents" (shisho) and wrote about it in the "Shisho" chapter of his Shobogenzo. In this chapter, he recorded a total of five occasions when he was able to look at a "transmission document" including that of Musai Ryoha. Let us look at these five ocassions in historical sequence: 1] The fall of 1223 when he traveled to China, he was introduced to Den (a monk who was in charge of the temple library), a Dharma descendent of Butsugen Sei'on of the Rinzai Yogi lineage.