Malaysia Begins Rectifying Major Flaws in Its Election System

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Islamic Political Parties and Democracy: a Comparative Study of Pks in Indonesia and Pas in Malaysia (1998-2005)

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by ScholarBank@NUS ISLAMIC POLITICAL PARTIES AND DEMOCRACY: A COMPARATIVE STUDY OF PKS IN INDONESIA AND PAS IN MALAYSIA (1998-2005) AHMAD ALI NURDIN S.Ag, (UIN), GradDipIslamicStud, MA (Hons) (UNE), MA (NUS) A THESIS SUBMITTED FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY SOUTHEAST ASIAN STUDIES PROGRAM NATIONAL UNIVERSITY OF SINGAPORE 2009 Acknowledgements This work is the product of years of questioning, excitement, frustration, and above all enthusiasm. Thanks are due to the many people I have had the good fortune to interact with both professionally and in my personal life. While the responsibility for the views expressed in this work rests solely with me, I owe a great debt of gratitude to many people and institutions. First, I would like to express my gratitude to Dr. Priyambudi Sulistiyanto, who was my principal supervisor before he transferred to Flinders University in Australia. He has inspired my research on Islamic political parties in Southeast Asia since the beginning of my studies at NUS. After he left Singapore he patiently continued to give me advice and to guide me in finishing my thesis. Thanks go to him for his insightful comments and frequent words of encouragement. After the departure of Dr. Priyambudi, Prof. Reynaldo C. Ileto, who was a member of my thesis committee from the start of my doctoral studies in NUS, kindly agreed to take over the task of supervision. He has been instrumental in the development of my academic career because of his intellectual stimulation and advice throughout. -

US Congress, Stand with Malaysians, Not Our Corrupt Government

November 28, 2016 US Congress, Stand with Malaysians, Not Our Corrupt Government By Nurul Izzah Anwar Earlier this month, tens of thousands of Malaysians took to the streets to demand free and fair elections and the end of status quo's endemic corruption. While our demands are not new, our protest demonstrated the remarkable fortitude of the Malaysian people in the face of mounting oppression by Prime Minister Najib Razak. In an attempt to prevent the rally, Najib took a page out of the dictator’s playbook and ordered the preemptive arrest of 11 opposition organizers. One of those detained is well known Malaysian activist, Maria Chin Abdullah, the 60-year-old chairwoman of the Coalition for Clean and Fair Elections (Bersih). She remains in solitary confinement under the draconian Security Offences Act — catering to hardcore terrorists, which vaguely criminalizes activities “contrary to parliamentary democracy.” Amnesty International has already designated those arrested as prisoners of conscience who must be released immediately and unconditionally. Abdullah joins my father, former Deputy Prime Minister and opposition leader Anwar Ibrahim, as one of many political prisoners in Malaysia. Currently imprisoned on politically-motivated charges, Anwar posed a threat to the ruling regime when he championed a multi-ethnic and multi-religious opposition movement that garnered 52 percent of the votes in the 2013 parliamentary election — a victory that was ultimately rendered hollow by the government’s gerrymandering. The United Nations has denounced my father imprisonment as arbitrary and in violation of international law. Dozens more have been targeted, harassed, or imprisoned under the false pretenses of national security simply because they dare to speak out against Najib’s authoritarian tendencies and corrupt practices. -

MARIA CHIN ABDULLAH GE14 CAMPAIGN MANIFESTO Maria Chin Abdullah Endorses the PAKATAN HARAPAN MANIFESTO Maria Chin Abdullah Endorses the PAKATAN HARAPAN MANIFESTO

Dignity. For All. MARIA CHIN ABDULLAH GE14 CAMPAIGN MANIFESTO Maria Chin Abdullah endorses the PAKATAN HARAPAN MANIFESTO Maria Chin Abdullah endorses the PAKATAN HARAPAN MANIFESTO DIGNITY IS BEING ABLE: TO PUT FOOD ON TO GIVE OUR THE TABLE FOR OUR CHILDREN AN FAMILY EDUCATION FOR A BRIGHTER FUTURE TO WALK ON THE STREETS SAFELY TO BREATHE CLEAN TO TREAT EACH AIR AND TO PROTECT OTHER AS EQUALS AND CONSERVE OUR AND WITH RESPECT ENVIRONMENT TO EXPRESS OUR OPINIONS WITHOUT FEAR “I, like you, have been fortunate to grow up in a Malaysia that is peaceful and inclusive. Sadly, times have changed so much. Every day, most of us have to fight hard to keep our dignity.” • GST means everything costs so much more. • Violence against women and children is on the rise, like other crimes. • Scholarships are less available, denying our children quality education. • Our country is now one of the most corrupt in Asia. • Our forests and native lands are being destroyed by corrupt developers. • Oppressive laws restrict our freedom of expression. Things are much worse than before. What can be done? Change for the better is possible. HOW WILL MARIA ACHIEVE HER GOALS? MY AIM WHAT I BELIEVE HOW I WILL DO IT A clean and fair I will work to put in place: government is the Legal reform foundation of a prosperous, • A Royal Commission of 1 healthy nation. Our leaders Inquiry (RCI) to review the must be freely, fairly and electoral system and CLEAN legitimately elected, at all processes AND FAIR levels of government, from • RCI on Local Council Federal to local. -

25 the Land Capability Classification of Sabah Volume 1 the Tawau Residency

25 The land capability classification of Sabah Volume 1 The Tawau Residency OdEXäxo] ßte©@x>a?®^ ®(^ Scanned from original by ISRIC - World Soil Information, as ICSU World Data Centre for Soils. The purpose is to make a safe depository for endangered documents and to make the accrued information available for consultation, following Fair Use Guidelines. Every effort is taken to respect Copyright of the materials within the archives where the identification of the Copyright holder is clear and, where feasible, to contact the originators. For questions please contact [email protected] indicating the item reference number concerned. The land capability classification of Sabah Volume 1 The Tawau Residency T-i2>S Land Resources Division The land capability classification of Sabah Volume 1 The Tawau Residency (with an Introduction and Summary for Volumes 1—4) P Thomas, F K C Lo and A J Hepburn Land Resource Study 25 Land Resources Division, Ministry of Overseas Development Tolworth Tower, Surbiton, Surrey, England KT6 7DY 1976 THE LAND RESOURCES DIVISION The Land Resources Division of the Ministry of Overseas Development assists develop ing countries in mapping, investigating and assessing land resources, and makes recommendations on the use of these resources for the development of agriculture, livestock husbandry and forestry; it also gives advice on related subjects to overseas governments and organisations, makes scientific personnel available for appointment abroad and provides lectures and training courses in the basic techniques of resource appraisal. The Division works in close cooperation with government departments, research institutes, universities and international organisations concerned with land resource assessment and development planning. -

Supernatural Elements in Tangon and Their Connection with Ethnic Ranau Dusun Beliefs

SUPERNATURAL ELEMENTS IN TANGON AND THEIR CONNECTION WITH ETHNIC RANAU DUSUN BELIEFS (Unsur-unsur Keajaiban dalam Tangon dan Perkaitannya dengan Konteks Kepercayaan Etnik Dusun di Ranau) Steefi Yalim [email protected] *Low Kok On [email protected] Faculty of Humanities, Arts & Heritage, University Malaysia Sabah. Published online: 5 December 2019 To Cite: Steefi Yalim and Low Kok On. (2019). Supernatural Elements in Tangon and Their Connection with Ethnic Ranau Dusun Beliefs. Malay Literature, 32(2), 185-206. Abstract Storytelling (monusui) is an oral tradition handed down from generation to generation among the Dusun ethnic group in Sabah. In the past, the narration of tangon (folktales) was a form of entertainment and an informal medium of education for the Dusun ethnic. A total of 44 tangon were successfully collected during fieldworks conducted in the state of Ranau. On examining the 44 tangon, 13 were found to be stories that contain supernatural elements or elements of magic. Among these are phenomena such as “humans being resurrected”, “humans giving birth to animals”, “humans morphing into birds”, and many more. These elements in tangon are the result of its creator’s imagination and creativity. The issue here is that if these elements are not analysed and highlighted, we will not be able to comprehend the imagination, creativity, and beliefs of the previous generations. The result of the analysis by way of interpretation of these supernatural elements in tangon shows that the Ranau Dusun ethnic group had a rich imagination and a great deal of creativity in conceiving these © Dewan Bahasa dan Pustaka. 2019. -

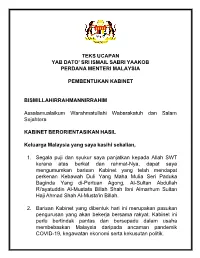

Teks-Ucapan-Pengumuman-Kabinet

TEKS UCAPAN YAB DATO’ SRI ISMAIL SABRI YAAKOB PERDANA MENTERI MALAYSIA PEMBENTUKAN KABINET BISMILLAHIRRAHMANNIRRAHIM Assalamualaikum Warahmatullahi Wabarakatuh dan Salam Sejahtera KABINET BERORIENTASIKAN HASIL Keluarga Malaysia yang saya kasihi sekalian, 1. Segala puji dan syukur saya panjatkan kepada Allah SWT kerana atas berkat dan rahmat-Nya, dapat saya mengumumkan barisan Kabinet yang telah mendapat perkenan Kebawah Duli Yang Maha Mulia Seri Paduka Baginda Yang di-Pertuan Agong, Al-Sultan Abdullah Ri'ayatuddin Al-Mustafa Billah Shah Ibni Almarhum Sultan Haji Ahmad Shah Al-Musta'in Billah. 2. Barisan Kabinet yang dibentuk hari ini merupakan pasukan pengurusan yang akan bekerja bersama rakyat. Kabinet ini perlu bertindak pantas dan bersepadu dalam usaha membebaskan Malaysia daripada ancaman pandemik COVID-19, kegawatan ekonomi serta kekusutan politik. 3. Umum mengetahui saya menerima kerajaan ini dalam keadaan seadanya. Justeru, pembentukan Kabinet ini merupakan satu formulasi semula berdasarkan situasi semasa, demi mengekalkan kestabilan dan meletakkan kepentingan serta keselamatan Keluarga Malaysia lebih daripada segala-galanya. 4. Saya akui bahawa kita sedang berada dalam keadaan yang getir akibat pandemik COVID-19, kegawatan ekonomi dan diburukkan lagi dengan ketidakstabilan politik negara. 5. Berdasarkan ramalan Pertubuhan Kesihatan Sedunia (WHO), kita akan hidup bersama COVID-19 sebagai endemik, yang bersifat kekal dan menjadi sebahagian daripada kehidupan manusia. 6. Dunia mencatatkan kemunculan Variant of Concern (VOC) yang lebih agresif dan rekod di seluruh dunia menunjukkan mereka yang telah divaksinasi masih boleh dijangkiti COVID- 19. 7. Oleh itu, kerajaan akan memperkasa Agenda Nasional Malaysia Sihat (ANMS) dalam mendidik Keluarga Malaysia untuk hidup bersama virus ini. Kita perlu terus mengawal segala risiko COVID-19 dan mengamalkan norma baharu dalam kehidupan seharian. -

Case Study Women in Politics: Reflections from Malaysia

International IDEA, 2002, Women in Parliament, Stockholm (http://www.idea.int). This is an English translation of Wan Azizah, “Perempuan dalam Politik: Refleksi dari Malaysia,” in International IDEA, 2002, Perempuan di Parlemen: Bukan Sekedar Jumlah, Stockholm: International IDEA, pp. 191-202. (This translation may vary slightly from the original text. If there are discrepancies in the meaning, the original Bahasa-Indonesia version is the definitive text). Case Study Women in Politics: Reflections from Malaysia Wan Azizah Women constitute half of humanity, and it follows that any decision-making, whether at the personal, family, societal or public levels, should be mindful of and involve the participation of women in the making of those decisions. Women’s political, social and economic rights are an integral and inseparable part of their human rights. Democracy is an inclusive process, and therefore in a functioning democracy, the points of view of different interest groups must be taken into account in formulating any decision. The interest and opinions of men, women and minorities must be part of that decision-making process. Yet far from being included in the decision-making process, women find themselves under-represented in political institutions. Numerous challenges confront women entering politics. Among them are lack of party support, family support and the "masculine model" of political life. Many feel that Malaysian society is still male dominated, and men are threatened by the idea of women holding senior posts. In the political sphere this is compounded by the high premium placed on political power. This makes some men even less willing to share power with women. -

THE UNREALIZED MAHATHIR-ANWAR TRANSITIONS Social Divides and Political Consequences

THE UNREALIZED MAHATHIR-ANWAR TRANSITIONS Social Divides and Political Consequences Khoo Boo Teik TRENDS IN SOUTHEAST ASIA ISSN 0219-3213 TRS15/21s ISSUE ISBN 978-981-5011-00-5 30 Heng Mui Keng Terrace 15 Singapore 119614 http://bookshop.iseas.edu.sg 9 7 8 9 8 1 5 0 1 1 0 0 5 2021 21-J07781 00 Trends_2021-15 cover.indd 1 8/7/21 12:26 PM TRENDS IN SOUTHEAST ASIA 21-J07781 01 Trends_2021-15.indd 1 9/7/21 8:37 AM The ISEAS – Yusof Ishak Institute (formerly Institute of Southeast Asian Studies) is an autonomous organization established in 1968. It is a regional centre dedicated to the study of socio-political, security, and economic trends and developments in Southeast Asia and its wider geostrategic and economic environment. The Institute’s research programmes are grouped under Regional Economic Studies (RES), Regional Strategic and Political Studies (RSPS), and Regional Social and Cultural Studies (RSCS). The Institute is also home to the ASEAN Studies Centre (ASC), the Singapore APEC Study Centre and the Temasek History Research Centre (THRC). ISEAS Publishing, an established academic press, has issued more than 2,000 books and journals. It is the largest scholarly publisher of research about Southeast Asia from within the region. ISEAS Publishing works with many other academic and trade publishers and distributors to disseminate important research and analyses from and about Southeast Asia to the rest of the world. 21-J07781 01 Trends_2021-15.indd 2 9/7/21 8:37 AM THE UNREALIZED MAHATHIR-ANWAR TRANSITIONS Social Divides and Political Consequences Khoo Boo Teik ISSUE 15 2021 21-J07781 01 Trends_2021-15.indd 3 9/7/21 8:37 AM Published by: ISEAS Publishing 30 Heng Mui Keng Terrace Singapore 119614 [email protected] http://bookshop.iseas.edu.sg © 2021 ISEAS – Yusof Ishak Institute, Singapore All rights reserved. -

How the Pandemic Is Keeping Malaysia's Politics Messy

How the Pandemic Is Keeping Malaysia’s Politics Messy Malaysia’s first transfer of power in six decades was hailed as a milestone for transparency, free speech and racial tolerance in the multiethnic Southeast Asian country. But the new coalition collapsed amid an all-too-familiar mix of political intrigue and horse trading. Elements of the old regime were brought into a new government that also proved short-lived. The turmoil stems in part from an entrenched system of affirmative-action policies that critics say fosters cronyism and identity-based politics, while a state of emergency declared due to the coronavirus pandemic has hampered plans for fresh elections. 1. How did this start? Two veteran politicians, Mahathir Mohamad and Anwar Ibrahim, won a surprising election victory in 2018 that ousted then-Prime Minister Najib Razak, who was enmeshed in a massive money-laundering scandal linked to the state investment firm 1MDB. Mahathir, 96, became prime minister again (he had held the post from 1981 to 2003), with the understanding that he would hand over to Anwar at some point. Delays in setting a date and policy disputes led to tensions that boiled over in 2020. Mahathir stepped down and sought to strengthen his hand by forming a unity government outside party politics. But the king pre-empted his efforts by naming Mahathir’s erstwhile right-hand man, Muhyiddin Yassin, as prime minister, the eighth since Malaysia’s independence from the U.K. in 1957. Mahathir formed a new party to take on the government but failed to get it registered. -

Mesyuarat Jawatankuasa Pilihan Khas Menimbang Rang Undang-Undang Bilik Mesyuarat Jawatankuasa 1, Blok Utama Bangunan Parlimen, Parlimen Malaysia

JPKRUU.23.10.2019 i MESYUARAT JAWATANKUASA PILIHAN KHAS MENIMBANG RANG UNDANG-UNDANG BILIK MESYUARAT JAWATANKUASA 1, BLOK UTAMA BANGUNAN PARLIMEN, PARLIMEN MALAYSIA RABU, 23 OKTOBER 2019 AHLI-AHLI JAWATANKUASA Hadir YB. Tuan Ramkarpal Singh a/l Karpal Singh [Bukit Gelugor] - Pengerusi YB. Puan Rusnah binti Aluai [Tangga Batu] YB. Tuan Larry Soon @ Larry Sng Wei Shien [Julau] YBhg. Datuk Roosme binti Hamzah - Setiausaha Tidak Hadir [Dengan Maaf] YB. Datuk Seri Panglima Wilfred Madius Tangau [Tuaran] YB. Dato’ Sri Azalina Othman Said [Pengerang] YB. Dr. Su Keong Siong [Kampar] YB. Dato’ Sri Dr. Haji Wan Junaidi bin Tuanku Jaafar [Santubong] URUS SETIA Encik Wan Ahmad Syazwan bin Wan Ismail [Ketua Penolong Setiausaha, Seksyen Pengurusan Kamar Khas (Bahagian Pengurusan Dewan Rakyat)] Cik Aiza binti Ali Raman [Penasihat Undang-undang II, Pejabat Penasihat Undang-undang (Pejabat Ketua Pentadbir)] Puan Lee Jing Jing [Jurubahasa Serentak Kanan I, Seksyen Jurubahasa dan Terjemahan (Bahagian Pengurusan Dewan Rakyat)] Cik Fatin ‘Izzati binti Mohd Radzi [Jurubahasa Serentak Kanan II, Seksyen Jurubahasa dan Terjemahan (Bahagian Pengurusan Dewan Rakyat)] Puan Wan Noor Zaleha binti Wan Hassan [Pegawai Penyelidik, Seksyen Antarabangsa dan Keselamatan (Bahagian Penyelidikan dan Perpustakaan)] Puan Siti Fahlizah binti Padlee [Pegawai Penyelidik, Seksyen Sains, Tenaga dan Teknologi (Bahagian Penyelidikan dan Perpustakaan)] HADIR BERSAMA Suruhanjaya Integriti Agensi Penguatkuasaan (SIAP) YBrs. Tuan Mohamad Onn bin Abd. Aziz [Setiausaha] Puan Eda Mazuin binti Abdul Rahman [Penasihat Undang-undang] samb/- Laporan Prosiding JK Pilihan Khas Menimbang Rang Undang-undang Bil.4/2019 JPKRUU.23.10.2019 ii HADIR BERSAMA Pusat Governans, Integriti dan Anti-Rasuah (GIACC) Encik Noor Rosidi bin Abdul Latif [Pengarah Bahagian Undang-undang] Polis Diraja Malaysia (PDRM) YBhg. -

ANFREL E-BULLETIN ANFREL E-Bulletin Is ANFREL’S Quarterly Publication Issued As Part of the Asian Republic of Electoral Resource Center (AERC) Program

Volume 2 No.1 January – March 2015 E-BULLETIN The Dili Indicators are a practical distilla- voting related information to enable better 2015 Asian Electoral tion of the Bangkok Declaration for Free informed choices by voters. Stakeholder Forum and Fair Elections, the set of principles endorsed at the 2012 meeting of the Participants were also honored to hear Draws Much Needed AES Forum. The Indicators provide a from some of the most distinguished practical starting point to assess the and influential leaders of Timor-Leste’s Attention to Electoral quality and integrity of elections across young democracy. The President of the region. Timor-Leste, José Maria Vasconcelos Challenges in Asia A.K.A “Taur Matan Ruak”, opened the More than 120 representatives from twen- Forum, while Nobel Laureate Dr. Jose The 2nd Asian Electoral Stakeholder ty-seven countries came together to share Ramos-Jorta, Founder of the State Dr. ANFREL ACTIVITIES ANFREL Forum came to a successful close on their expertise and focus attention on the Marí Bim Hamude Alkatiri, and the coun- March 19 after two days of substantive most persistent challenges to elections in try’s 1st president after independence discussions and information sharing the region. Participants were primarily and Founder of the State Kay Rala 1 among representatives of Election from Asia, but there were also participants Xanana Gusmão also addressed the Management Bodies and Civil Society from many of the countries of the Commu- attendees. Each shared the wisdom Organizations (CSOs). nity of Portuguese Speaking Countries gained from their years of trying to (CPLP). The AES Forum offered represen- consolidate Timorese electoral democ- Coming two years after the inaugural tatives from Electoral Management Bodies racy. -

Racialdiscriminationreport We

TABLE OF CONTENTS Glossary ............................................................................................................................................................................ 1 Executive Summary...................................................................................................................................................... 3 Definition of Racial Discrimination......................................................................................................................... 4 Racial Discrimination in Malaysia Today................................................................................................................. 5 Efforts to Promote National Unity in Malaysia in 2018................................................................................... 6 Incidences of Racial Discrimination in Malaysia in 2018 1. Racial Politics and Race-based Party Politics........................................................................................ 16 2. Groups, Agencies and Individuals that use Provocative Racial and Religious Sentiments.. 21 3. Racism in the Education Sector................................................................................................................. 24 4. Racial Discrimination in Other Sectors................................................................................................... 25 5. Racism in social media among Malaysians........................................................................................... 26 6. Xenophobic