Semantic Changes of English Loan Words Found In

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

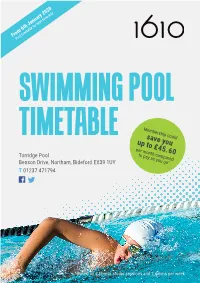

Swimming Pool Timetable

From 6th January 2020 Pool timetable for term time only Membership could SWIMMING POOL save you up to £45.60 per month compared TIMETABLE to pay as you go* Torridge Pool Benson Drive, Northam, Bideford EX39 1UY T 01237 471794 *Based on 2 fitness studio sessions and 2 swims per week TORRIDGE POOL Benson Drive, Northam, Bideford, Devon EX39 1UY T 01237 471794 FROM 6/1/2020 Main Pool - Term Time Learner Pool - Term Time Time Mon Tue Wed Thu Fri Sat Sun Mon Tue Wed Thu Fri Sat Sun Time 06.00 06.00 07.00 07.00 06.30-08.30 06.30-09.00 06.30-09.00 Early birds 06.30-09.00 06.30-08.30 Early birds Early birds Early birds Early birds 08.00 08.00 08.30-09.15 Water Pilates 09.00 09.00 09.00-10.00 09.00-10.00 09.00-10.00 09.00-10.00 Aquafit Aquafit Aquafit Early birds 09.00-10.30 09.00- 09.00-11.00 Swim lessons 09.00-11.15 13.30 Swim lessons 10.00 10.00-11.00 Schools 10.00 10.00-11.00 09.00-12.00 09.45-11.15 09.00-12.00 Parent & 09.00-12.00 09.00-12.00 Golden Aquafit Schools Schools Just swim toddler Schools Just swim Group swim Swim lessons 10.00-12.30 10.00-12.00 09.00-13.00 Swim lessons 11.00 Just swim Just swim Parent & toddler 10.30-12.00 11.00 11.00-12.00 10.00-11.30 Swim lessons 11.00-12.00 11.00-12.00 Just swim Golden Disability swim† Parent & toddler Group swim 09.00-12.00 10.00-12.00 11.45-12.30 11.45-12.30 12.00 Just swim Just swim 12.00 12.00-13.00 12.00-13.00 12.00-13.00 Lunchtime lanes Lunchtime lanes 12.15-13.15 12.15-13.15 Just swim 12.15-13.15 12.15-13.15 12.30-13.30 12.30-13.30 12.30-13.30 Inflatafun Fun 'n' floats Fun 'n' floats Fun -

Australian Official Journal Of

Vol: 22 , No. 49 11 December 2008 AUSTRALIAN OFFICIAL JOURNAL OF TRADE MARKS Did you know a searchable version of this journal is now available online? It's FREE and EASY to SEARCH. Find it at http://pericles.ipaustralia.gov.au/ols/epublish/content/olsEpublications.jsp or using the "Online Journals" link on the IP Australia home page. The Australian Official Journal of Designs is part of the Official Journal issued by the Commissioner of Patents for the purposes of the Patents Act 1990, the Trade Marks Act 1995 and Designs Act 2003. This Page Left Intentionally Blank (ISSN 0819-1808) AUSTRALIAN OFFICIAL JOURNAL OF TRADE MARKS 11 December 2008 Contents General Information & Notices IR means "International Registration" Amendments and Changes Application/IRs Amended and Changes ...................... 18143 Registrations/Protected IRs Amended and Changed ................ 18144 Registrations Linked ............................... 18140 Applications for Extension of Time ...................... 18143 Applications for Amendment .......................... 18143 Applications/IRs Accepted for Registration/Protection .......... 17690 Applications/IRs Filed Nos 1273232 to 1273980 ............................. 17679 Applications/IRs Lapsed, Withdrawn and Refused Lapsed ...................................... 18145 Withdrawn..................................... 18146 Refused ...................................... 18146 Assignments,TransmittalsandTransfers.................. 18146 Cancellations of Entries in Register ...................... 18149 Corrigenda..................................... -

Where Is the Great Barrier Reef? Pdf, Epub, Ebook

WHERE IS THE GREAT BARRIER REEF? PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Nico Medina | 112 pages | 01 Nov 2016 | Penguin Putnam Inc | 9780448486994 | English | New York, United States Where is the Great Barrier Reef? PDF Book Physiographic Diagram of Australia. Demand valve oxygen therapy First aid Hyperbaric medicine Hyperbaric treatment schedules In-water recompression Oxygen therapy Therapeutic recompression. Britannica Quiz. Seabirds will land on the platforms and defecate which will eventually be washed into the sea. Diving mask Snorkel Swimfin. The types of corals that reproduced also changed, leading to a "long-term reorganisation of the reef ecosystem if the trend continues. In July , a new zoning plan took effect for the entire Marine Park, and has been widely acclaimed as a new global benchmark for marine ecosystem conservation. From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia. Lying off the Queensland coast, that great system of coral reefs and atolls owes its origin to a combination of continental drift into warmer waters , rifting, sea-level change, and subsidence. It is important to know how far out from land the reef is located as well. Retrieved 3 September Diving support equipment. Four traditional owners groups agreed to cease the hunting of dugongs in the area in due to their declining numbers, partially accelerated by seagrass damage from Cyclone Yasi. Flat reefs known as planar reefs are found in the northern and southern parts, near Cape York Peninsula, Princess Charlotte Bay and Cairns. Archived from the original on 16 October Region" PDF. Bibcode : LimOc.. Archived from the original on 7 May Above the surface, the plant life of the cays is very restricted, consisting of only some 30 to 40 species. -

The Divers Logbook Free

FREE THE DIVERS LOGBOOK PDF Dean McConnachie,Christine Marks | 240 pages | 18 May 2006 | Boston Mills Press | 9781550464788 | English | Ontario, Canada Printable Driver Log Book Template - 5+ Best Documents Free Download A dive log is a record of the diving history of an underwater diver. The log may either be in a book, The Divers Logbook hosted softwareor web based. The log serves purposes both related to safety and personal records. Information in a log may contain the date, time and location, the profile of the diveequipment used, air usage, above and below water conditions, including temperature, current, wind and waves, general comments, and verification by the buddyinstructor or supervisor. In case of a diving accident, it The Divers Logbook provide valuable data regarding diver's previous experience, as well as the other factors that might have led to the accident itself. Recreational divers are generally advised to keep a logbook as a record, while professional divers may be legally obliged to maintain a logbook which is up to date and complete in its records. The professional diver's logbook is a legal document and may be important for getting employment. The required content and formatting of the professional diver's logbook is generally specified by the registration authority, but may also be specified by an industry association such as the International Marine Contractors Association IMCA. A more minimalistic log book for recreational divers The Divers Logbook are only interested in keeping a record of their accumulated experience total number of dives and total amount of time underwatercould just contain the first point of the above list and the maximum depth of the dive. -

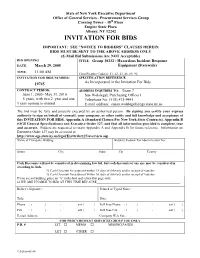

Invitation for Bids

State of New York Executive Department Office of General Services - Procurement Services Group Corning Tower - 38th Floor Empire State Plaza Albany, NY 12242 INVITATION FOR BIDS IMPORTANT: SEE “NOTICE TO BIDDERS” CLAUSES HEREIN BIDS MUST BE SENT TO THE ABOVE ADDRESS ONLY (E-Mail Bid Submissions Are NOT Acceptable) BID OPENING TITLE: Group 38232 - Hazardous Incident Response DATE: March 29, 2005 Equipment (Statewide) TIME: 11:00 AM Classification Code(s): 41, 42, 43, 46, 85, 92 INVITATION FOR BIDS NUMBER: SPECIFICATION REFERENCE : As Incorporated in the Invitation For Bids 19745 CONTRACT PERIOD: ADDRESS INQUIRIES TO: Team 7 June 1, 2005- May 31, 2010 Sue Wolslegel, Purchasing Officer I 5 years, with two 2 year and one Telephone No. (518) 473-9441 1 year options to extend E-mail address: [email protected] The bid must be fully and properly executed by an authorized person. By signing you certify your express authority to sign on behalf of yourself, your company, or other entity and full knowledge and acceptance of this INVITATION FOR BIDS, Appendix A (Standard Clauses For New York State Contracts), Appendix B (OGS General Specifications) and Executive Order 127, and that all information provided is complete, true and accurate. Bidders are requested to retain Appendix A and Appendix B for future reference. Information on Executive Order 127 may be accessed at: http://www.ogs.state.ny.us/legal/ExeOrder127/overview.asp Name of Company Bidding: Bidder's Federal Tax Identification No.: Street City State Zip County Cash Discounts will not be considered in determining low bid, but cash discounts of any size may be considered in awarding tie bids. -

Thebabasling ® Pao Papoose™ Wuti Wrap™

2014 Hall 11.1 - Kind + Jugend Sep 11 - 14 DIRECTORY ™ STAND A050 thebabasling ® for international distributor ™ opportunities, please email pao papoose [email protected] or call ™ wuti wrap +44(0)1273 320 590 2 3 UK Pavilion exhibitors - A-Z Hall 11.1 Visit the UK’s nursery trade Company Name association on stand A049 A050 Kub Products Ltd A053 Welcome to the 2014 UK Pavilion, organised by the representing its members at a European level and BabaSlings Baby Products Association (BPA), bringing a wealth is also the Accredited Trade Organisation (ATO) Babycare TENS Healthcare D089 LCR Hallcrest A035a of exciting new and established British products for UK Trade & Investment (UKTi) responsible for from over 60 companies all under one convenient roof. allocating Trade Access Programme (TAP) funding to Babycup Ltd C069 Little Champ D071 We hope you will enjoy some great British hospitality enable British companies to exhibit their products in Bambino Mio C041 Little Life B058 in our Networking Arena and take the opportunity Europe and worldwide. As part of this initiative,you Belt up Baby A043a MaByLand A041 to find out more about what our exhibitors have to are cordially invited to join the BPA’s Networking Event offer. Each company is detailed in this Directory and with free drinks and nibbles at the end of the first Belt Upp A037a Melobaby A043 the location map in the centre will conveniently help day on Thursday 11th September – we look forward Bo Peep C078a Milton Pharmaceutical A031a you to locate each stand. to seeing you there! Come -

Learning to Swim Has Never Been So Much Fun! the Swimming Aid Kids Want to Wear!

Learning to swim has never been so much fun! The Swimming Aid Kids Want to Wear! © ToTo orderorder youryour SwimFinSwimFin www.swimfin.co.ukwww.swimfin.co.uk CustomerCustomer ServiceService 01604 416916416916 What does SwimFin offer you? Meet Finley the Friendly Shark Inspires confidence, imagination and play a sweet hale r is fi n r W is pe le a ap il n c S K l Ultra Safe - stays in one place, no tipping or slipping and is highly visible e v e r fi n n Works across all four swim strokes - multi-stroke functional fi y t t e Ages 2+ - makes learning to swim fun for any age, any size and any ability r p a s i Makes the learning to swim process quicker and easier sh fi Violet No restrictive movements and helps maintain a natural swimming position ldfi sh is a Go ha pp y fr fi a ien is d Used as a training and teaching tool n l sh y fi lfi e n © g “SwimFin is unique in every way. Getting kids down to the pool or into n the water suddenly becomes a pleasure and not a chore. Kids want to A w? Sw no im strap on their fin and jump in with their friends. SwimFin’s non- k m restrictive nature means your child learns to swim in a natural u i o n g position without any restriction around the arms or legs. We aim y h d i to make learning to swim a pleasurable experience for all family e l D p members. -

Using Sea Turtle Biomimetics for Increasing Swimming Efficiency in Humans University of the South Pacific

Using Sea Turtle Biomimetics for Increasing Swimming Efficiency in Humans University of the South Pacific University of Twente. Internship Author: Supervisor: Thomas Schot s0199958 Dr. David Aitchison June 24, 2015 Contents 1 Preface 1 2 Introduction 2 3 Problem Specification 3 3.1 Swimming Behavior . 3 3.2 Translation to Mechanical Model . 3 3.3 Requirements . 4 4 Concept Development 5 4.1 Concept 1 . 5 4.2 Concept 2 . 5 4.3 Concept 3 . 6 4.4 Feathering motion . 7 4.4.1 Concept 1 . 7 4.4.2 Concept 2 and 3 . 7 5 Preliminary Design 9 5.1 Analytical Calculations . 9 5.1.1 Lift Coefficient, Drag Coefficient and Thrust Coefficient . 9 5.1.2 Concept 1 . 10 5.1.3 Concept 2 . 13 5.1.4 Concept 3 . 18 6 Detailed Design 25 6.1 Flipper Morphology . 25 6.1.1 Flipper Design in SolidWorks . 25 6.2 Feathering Mechanism . 26 6.3 Analysis in SolidWorks . 28 6.3.1 Computational Fluid Dynamics . 28 6.3.2 Analytical Calculations . 30 6.3.3 Finite Element Analysis . 36 6.4 Material Selection . 44 7 Final Design 45 7.1 Concept Selection . 45 7.2 Dimensional Optimization . 45 7.2.1 Analysis in SolidWorks - Mechanism . 46 7.2.2 Analysis in SolidWorks - Flipper . 50 7.2.3 Material Justification . 53 7.3 Mass and Material Costs . 53 7.4 Assembly . 54 7.5 Artist's impression . 55 8 Conclusion 56 9 Discussion and Remarks 57 10 Acknowledgement 59 References 60 Appendices I A Determination of CL and CD in SolidWorks I B Technical Drawing Concept 1 V C Technical Drawing Concept 2 VIII D Technical Drawing Flipper XIII E Technical Drawing Final Concept XIV 1 Preface The field of engineering of this project lies within Computational Fluid Dynamics, Finite Element Analysis and mechanisms. -

|||GET||| Scientific Diving Techniques a Practical Guide for the Research

SCIENTIFIC DIVING TECHNIQUES A PRACTICAL GUIDE FOR THE RESEARCH DIVER 2ND EDITION DOWNLOAD FREE John N Heine | 9781930536685 | | | | | Scientific and archaeological diving projects Retrieved 21 March Duarte, N. The main objective of this work was to define the best location to shellfish beds in this coastal lagoon, considering growth requirements, physical conditions and 3 hydrodynamic indicators: average current velocity, maximum flood current velocity and residence time, which were calculated using time series of water level and longitudinal component of velocity variations time series, which covered complete tidal cycles. Sea Frontiers, 35 3 [May-June ]: Help Learn to edit Community portal Recent changes Upload file. The scheme provides certification of divers and accreditation of training establishments, develops training courses to meet industry needs, and promotes the mobility of ADAS licence holders around the world. They are underwater tour guidesand as such are expected to know the level of certification and fitness needed for the planned dive, but are not generally considered responsible for ensuring that the customers are competent to the level of certification they hold, or for the personal safety of the customers during the dive. Retrieved 24 September Gamito, S. Useful tips are included throughout to guide users in gaining the maximum benefit from ROV technology in deep water applications. Aquarium divers normally hold some form of professional qualification, either as a commercial diver or a recognised recreational certification -

ORDER Denying 36 Defendant's Motion to Dismiss. the Court

Wahoo International, Inc. v. Phix Doctor, Inc. et al Doc. 49 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT 9 SOUTHERN DISTRICT OF CALIFORNIA 10 WAHOO INTERNATIONAL, INC, CASE NO. 13cv1395-GPC(BLM) 11 Plaintiff, ORDER DENYING DEFENDANT’S vs. MOTION TO DISMISS 12 [Dkt. No. 36.] 13 PHIX DOCTOR, INC., a Florida Corporation; and DOES 1-10, 14 Defendants. 15 16 Before the Court is Defendant Phix Doctor, Inc.’s (“Phix Doctor” or 17 “Defendant”) motion to dismiss for failure to state a claim pursuant to Federal Rule of 18 Civil Procedure (“Rule”) 12(b)(6).1 Plaintiff Wahoo International, Inc.’s (“Wahoo” or 19 “Plaintiff”) filed an opposition on May 2, 2014. (Dkt. No. 38.) A reply was filed on 20 May 20, 2014. (Dkt. No. 45.) Based on the reasoning below, the Court DENIES 21 Defendant’s motion to dismiss. 22 / / / / 23 24 1Defendant also moves for judgment on the pleadings pursuant to Federal Rule of Civil Procedure 12(c). (Dkt. No. 36.) Rule 12(c) provides that a party may move 25 for judgment on the pleadings after the pleadings have closed. Fed. R. Civ. P. 12(c). In this case, the pleadings have not closed since no answer has been filed. 26 Accordingly, Defendant may not move pursuant to Rule 12(c). See Doe v. U.S., 419 F.3d 1058, 1061-62 (9th Cir. 2005) (motion for judgment on the pleadings before 27 answer was filed was premature and should have been denied). The Court also notes that in the first paragraph of Defendant’s brief, it states that it is also moving in the 28 alternative for change in venue. -

Learning to Swim Has Never Been So Much Fun, with the Swimming Aid Kids Want to Wear!

Get your FIN on! Learning to swim has never been so much fun, with the swimming aid kids want to wear! www.swimfin.co.uk The perfect swimming aid for every mini shark adventure hen a child puts on W a SwimFin©, they COLOURFUL RANGE immediately become more active, INCLUDING NEW ‘LIME’ FIN! playing, building confidence, learning, experimenting and having FUN! SwimFin© plays a psychological part in learning to swim, even before a lesson has started. Kids love the feeling of safety and security SwimFin© gives them, while it motivates and encourages imagination and play. and more natural swimming position. SwimFin© is the first truly new SwimFin© compensates for different development in the teaching of swimming abilities, providing as much support as the for decades – tried and tested to swimmer needs, yet giving confidence to assist anyone in learning to swim. even the most timid learner. SwimFin© Unlike arm-bands, noodles or other is also a flotation device that complies to keep an adult afloat. And after it has devices, SwimFin© works in harmony with international safety standards EN71 done it’s job as a learning aid, SwimFin© with the body, helping to develop a better and EN13138, providing enough buoyancy will always find use as a fun water toy. DID YOU KNOW? SWIMMING HELPS BUILD MUSCLE What does SwimFin offer you? ✔ Inspires confidence, imagination and play ✔ Ultra Safe - stays in one place, no tipping or slipping and is highly visible ✔ Works across all four swim strokes - multi-stroke functional ✔ Makes the learning to swim process quicker and easier ✔ No restrictive movements and helps maintain a natural swimming position ✔ Used as a training and teaching tool © SwimFin is unique in every way! Getting kids down to the pool or into the water suddenly becomes a pleasure and not a chore. -

Spearfishing Catalog 2014

Spearfishing 2014 540B1EG 540B2EG 540B3EG E-GLASS DESCRIPTION Very short bifins for spearfishing in the waves and in shallow waters. A fast mover fin, made for tight turns and quick kick. Composite blades to stock up on maximum energy throughout the bending. TECHNOLOGY Technology : prepreg curing process Fabric : E-glass Resin : epoxy Performance : 30 to 40% more responsive than plastic SPECIFICATIONS Height of blade : 540 mm Width of blade : 235 mm Flat blade for made-to-measure footpocket (free heel) Blade with an angle of 15° to fit in full footpocket 3 kinds of varying hardness that are most likely to suit your style and body type : 540B1EG : soft 540B2EG : medium 540B3EG : hard Weight with made-to-measure footpocket = 1,5kg Weight with full footpocket = 1,9kg T profiles along the edges to ensure a good drive and a channeling of the water FOOTPOCKETS 2 kinds of footpockets : - Made-to-measure footpocket : Size 35 to 50 (3 to 15), free heel for better stroke - Tuned full footpocket : cut out footpocket to get a lighter and more responsive swimfin. Beuchat Mundial : 41-42, 43-44, 45-46, 47-48 Imersion : 38-40, 40-42, 42-44, 44-46 Pathos : 36-38, 38-40, 40-42, 42-44, 44-46, 46-48, 48-50 540B1SG 540B2SG 540B3SG S-GLASS DESCRIPTION Very short bifins for spearfishing in the waves and in shallow waters. A fast mover fin, made for tight turns and quick kick. Composite blades to stock up on maximum energy throughout the bending. Better strength thanks to S Glass. TECHNOLOGY Technology : prepreg Fabric : S-glass fibre Resin : epoxy Performance