History of the Fort

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Battle of Groton Heights; and Such, As Far As My Imperfect Manner and Language Can De Scribe, a Part of the Sufferings Which We Endured

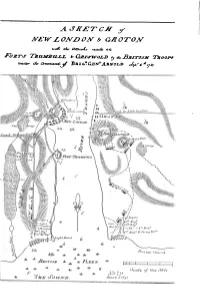

A J'A' A' Z CAZ / AVA. W. A. OA/AO OAM & G.A.' O2"OAV wººt tº accrucº, zaazde on. ZºoZº. Zºey Z Rzz Azºzzzz & Gºrers wozz, 6 a. Azzzzºw Tºrooze unar 4 ament ºf Barcº Gen”An sold 24, e “y, Ø */ %|ſº s % % 30 % - - ~ %ag tº steritagº: 3% º -> # | º 3A º º o?” % # == ſaw Łow \ - - + * |SV%, ’4%. % - SNM //- 4%. $º-º-º:- % = § ſº sººn & = ~ S-tº 5 \"\º - - ºvº. Y. & = </ - ****** * = \ | à s ºf 3% w S - \ \| º -T %\ % 4 : § ? $3. E 3. *Sº 2- Sº #E. N 5s - SS & M." s JT */ 5,27% yes.” Š toº Rººf §º **º-R-3° *...* --i- º + 4 *}”y 1- Pair t-8". How?" - ** Batº M. Jersey yew.” --- *** Á ty't Jouse 6 - 4° 6 “. .” 4- * = 1st...a - -ā- o Arra-rºw 4. -à- * Azazz. “ EEEEEE *}caze of one 4//e * * * -*- AL * * 6 - - v" * * .*** ; : * *tack 1 edge *- 7#z Jozzava. THE BATTLE Of GROTON HEIGHTS: w A COLLECTION OF NARRATIVES, OFFICIAL REPORTS, RECORDS, ETC. of The STORMING OF FORT GRISWOLD, T11 E MASSACRE OF ITS GARRISON, AND THE BURNING OF NEW LONDON BY BRITISH TROOPS UNDER THE COMMAND OF BRIG-GEN. BENEDICT ARNOLD, ON THE SIXTH OF SEPTEMBER, 1781. WITH AN INTRODUCTION AND NOTES. %ZZ-cc./a/ By WILLIAM W. HARRIS. ZLZ USTRATED WITH EAVGRA V/AWGS AAWD MAPS. REVISED AND ENLARGED, witH ADDITIONAL Notes, By CHARLES ALLYN. "Zebulon and Naphtali were a people that jeoparded their lives unto the death in the high places of the field.” – 9adres, 5 Chapt. 18 Verse. [Inscription on Monument.] +. *NEw LoNDoN, CT.: C H A R L ES ALLY N. -

Connecticut Connections: the Places That Teach Us About Historical Archaeology

CONNECTICUT_CONNECTIONS_THE_PLACES_THAT 2/28/2017 4:13 PM Connecticut Connections: The Places That Teach Us About Historical Archaeology LUCIANNE LAVIN Institute for American Indian Studies To many people the word “archaeology” invokes images of Egyptian pyramids, Aztec temples, the treasures of ancient Rome. If they are aware of North American archaeology, they usually picture archaeology sites far west of New England – 10,000-year-old early man sites on the Plains or the Southwestern Pueblo cliff dwellers. They rarely consider Connecticut as a center of important archaeological activity. But it is! As the preceding articles on Connecticut archaeology aptly illustrate, our state’s rich multi-cultural heritage is reflected and informed by its archaeology sites. Connecticut contains thousands of prehistoric, historic, industrial, and maritime archaeological sites created by the ancestors of its various ethnic residents. Many are thousands of years old. Because Connecticut History is specifically an history journal, I will restrict my discussion to post- European contact archaeology sites. Archaeology sites provide insights on fascinating and important stories about Connecticut that often are not found in local history books. Domestic, commercial, and industrial archaeology sites provide clues to the diverse lifestyles of Connecticut’s residents through time, their community relationships and events, and the cultural changes that modified those lifestyles and connections. But where can one go to learn about Connecticut archaeology? The best places are the sites themselves. Plan an excursion to some of these wonderful archaeology localities where you can spend enjoyable, quality time with family and friends while learning about a specific aspect of local, regional, and even national history. -

Connecticut's Part in the Lexington Alarm By

The f thepomfrettimes1995.org PInformingom the local community retfor 22 years TVolumeimes 23 No.4 JULY 2017 By Connecticut’s Part in the Lexington Alarm Jim Platt n April 19, 1775 the British Perhaps Connecticut’s greatest troops marched contribution to the war was the fact into Lexington, that it furnished many supplies to Massachusetts the Continental Army. To General in an attempt George Washington, Connecticut was Oto capture what they thought “The Provision State”. was an arsenal of powder and shot. The local Militia resisted setts and the rest were sent home. them and the alarm went out A company of horse soldiers were for reinforcements. Throughout formed in Woodstock and they also New England the alarm was spread went to Boston. Each man reported by men on horseback. Israel Bessel to have with him 20 day provisions was charged with spreading the word and 60 rounds of ammunition. The throughout Connecticut and he, like men from Connecticut had on their the other alarmers, rode a horse and standards or flags the motto of “qui carried a drum. By the 27th of April transtulit sustinet” which translates to “God who transplanted us here will the word had reached as far south as It was reported in the diary of one support us.” General Ward was the troop commander in Roxbury and General Baltimore and by the 11th of May it of the local officers that about 1,000 Putnam was the commander in chief and in charge at Cambridge. During the rest of April and May there was no action on either side and had reached Charleston, South Caro- men assembled in Pomfret ready to lina. -

SPL115A Copy

MAPPING: NORTHERN BATTLES Using a grid system helps you locate places in the world. A grid system is made up of lines that come together to form squares. The squares divide a map into smaller pieces, making it easier to \ nd important places. Learning how to use a grid system is easy, and will teach you an important location skill. Example: In July 1777, the British Army took control of Mount Independence. Hundreds of soldiers from America, Great Britain, and Germany are buried in unmarked graves on top of Mount Independence. Mount Independence is located at ( 4,4 ). Locate Mount Independence at ( 4,4 ), by putting your \ nger on the number 1 at the bottom of the grid. Slide over to 4 and up to 4. Mount Independence is located in the square created where these two numbers come together. 6 5 Mount 4 Ind. 3 2 1 1 2 3 4 5 678 9 Directions: In this activity, you will use a grid system to locate important Revolutionary War forts and battles in the North. 1. Follow the example above for locating each fort or battle by going over and up. If a fort or battle is located at ( 4,4 ), go over to 4 and up to 4. 2. When you locate a fort or battle on the grid, color in the square with a coloring pencil. If the fort or battle was won by the Americans, color the square blue. If the fort or battle was won by the British, color the square red. 3. The \ rst one has been done for you as an example. -

Batt~E of Fort Griswold, - By ~T J

E 241 ROTON HEIGHTS, .GS H46 1890 WT'l'll .\ \ \ Hll \ 'l'l\' E O~' 'I'll to: BATT~E OF FORT GRISWOLD, - BY ~T J . l'lt~ 111 ·:.\JJ'~TJ.: \I>, \\. llll \\' ' " TllE FllH'I' \ 'I' TIJE Ti\IE, 1890. -. DESCRIPTION OF THE - OK GROTON.HEIGHTS , NEW LONDON. C~R~ .:J' -- VI :ElT~l!' ~'\.'l,, 'T;;>U~h~~.. 1890. ---- THE BATTLE MONUMENT. In the year r826 a number of gentlemen in Groton. feeling that the tragic events occurrring in the neighbor hood in 1781 should he more properly commemorated, organized as an association for the purpose of erecting a monument. An application to the legislature for a charter was granted, and a lottery in aid of the work was legalizeJ by special act. The corner stone was laid September 6th of that year, and the 6th of September, i830, it was dedi cated with imposing ceremonies. During the centennial year, important repairs and changes were made. In form it is now an obelisk, twenty-two feet square at the base, and eight and one-half feet at base of pyrami<lon, resting on a die twenty-four feet square, which in turn rests upon a base twenty-six feet square. Its material is granite, quarried in the neighborhood. Its whole height is one hundred and thirty-five feet, and its summit, which is reached by a spiral stairway of one hundred and sixty-six stone steps, is two hundre<l and sixty-five feet above the waters of the bay. From this point a picture of sea and land of almost unrivalled beauty is presented, well repaying the visitor for the toil of ascent. -

Bushnell Family Genealogy, 1945

BUSHNELL FAMILY GENEALOGY Ancestry and Posterity of FRANCIS BUSHNELL (1580 - 1646) of Horsham, England And Guilford, Connecticut Including Genealogical Notes of other Bushnell Families, whose connections with this branch of the family tree have not been determined. Compiled and written by George Eleazer Bushnell Nashville, Tennessee 1945 Bushnell Genealogy 1 The sudden and untimely death of the family historian, George Eleazer Bushnell, of Nashville, Tennessee, who devoted so many years to the completion of this work, necessitated a complete change in its publication plans and we were required to start anew without familiarity with his painstaking work and vast acquaintance amongst the members of the family. His manuscript, while well arranged, was not yet ready for printing. It has therefore been copied, recopied and edited, However, despite every effort, prepublication funds have not been secured to produce the kind of a book we desire and which Mr. Bushnell's painstaking work deserves. His material is too valuable to be lost in some library's manuscript collection. It is a faithful record of the Bushnell family, more complete than anyone could have anticipated. Time is running out and we have reluctantly decided to make the best use of available funds by producing the "book" by a process of photographic reproduction of the typewritten pages of the revised and edited manuscript. The only deviation from the original consists in slight rearrangement, minor corrections, additional indexing and numbering. We are proud to thus assist in the compiler's labor of love. We are most grateful to those prepublication subscribers listed below, whose faith and patience helped make George Eleazer Bushnell's book thus available to the Bushnell Family. -

Illlllllillllilil;; CATEGORY ACCESSIBLE OWNERSHIP STATUS (Check One) to the PUBLIC

Form 10-300 UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR STATE: (July 1969) NATIONAL PARK SERVICE Connecticut COUNTY: NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES New London INVENTORY - NOMINATION FORM FOR NPS USE ONLY ENTRY NUMBER (Type all entries — complete applicable sections) COMMON: Fort Griswold AND/OR HISTORIC: STREET AND NUMBER: Bounded by Baker Avenue. Smith Street« Park Aven jand. the CITY OR TOWN: Grot on COUNTY: Connecticut 0 New ODT Illlllllillllilil;; CATEGORY ACCESSIBLE OWNERSHIP STATUS (Check One) TO THE PUBLIC District Q Building E Public Public Acquisition: Occupied Yes: 1 1 Restricted Site Q Structure D Private Q] In Process Unoccupied1 1 . j ' — ' r> . icl Unrestricted D Object D Both | | Being Consi< Preservation work -^^ in progress ' — ' PRESENT USE (Check One or More as Appropriate) \ | Agricultural | | Government 09 Park I | Transportation f~l Comments [^] Commercial D Industrial | | Private Residence Q Other CS [~| Educational 1 1 Military I I Religious | | Entertainment CD Museum I | Scientific OWNER'S NAME: ATE State of Connecticut __ state Park and Forest Commission Connecticut STREET AND NUMBER: St.atft Offinft Rn-nding CTY OR TOWN: STATE: ~ot>'CODE Hartford Connecticut COURTHOUSE, REGISTRY OF DEEDS, ETC: Municipal Building TY:UN STREET AND NUMBER: ewLondon Cl TY OR TOWN: STATE Groton Connecticut Tl tt-E OF SURVEY: Connecticut Historic Structures and Landmarks Survey DATE OF SURVEY: m D Federal State County Loca DEPOSITORY FOR SURVEY RECORDS: Connecticut Historical Commission STREET AND NUMBER: o 75 Sim Street CITY OR TOWN: STATE: Hartford C onnect icut C& 0 (Check One) CD Excellent ED Good CD. Fair S Deteriorated a Ruins ED Unexposed CONDITION (Check One) (Check One) [jj) Altered CD Unaltered ED Moved Q?J Original Site DESCRIBE THE PRESENT AND ORIGINAL (if known) PHYSICAL APPEARANCE Fort Griswold was built between 1775 s-nd 78 for the defense of the Groton and New London shore. -

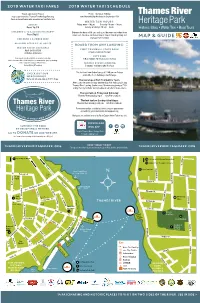

Thames River Heritage Park GO to DONATE on OUR WEBSITE

2019 WATER TAXI FARES 2019 WATER TAXI SCHEDULE Tickets and Season Passes Friday – Sunday & holidays may be purchased at ThamesRiverHeritagePark.org. from Memorial Day Weekend to September 15th Cash and credit cards also accepted on the Water Taxi. WATER TAXI HOURS: ADULTS Friday: noon – 10 p.m. Saturday: 10 a.m. – 10 p.m. Round Trip $10 Sunday & holidays: 10 a.m. – 9 p.m. Historic Sites • Water Taxi • Boat Tours * CHILDREN 4-12 & ACTIVE MILITARY Between the hours of 10 a.m. and 7 p.m. the water taxi makes three ONE RIVER. A THOUSAND STO- Round Trip $5 stops each hour in a continuous hop on-hop off loop beginning and MAP & GUIDE CHILDREN 3 & UNDER FREE ending at Fort Trumbull. ALL RIDES AFTER 6 P.M. ARE $5 BOARD FROM ANY LANDING: SEASON PASSES AVAILABLE FORT TRUMBULL STATE PARK Adult $50 Child $30 in New London: on the hour All Rides, All Season CITY PIER Passengers may disembark & re-board at each stop. in New London: 20 minutes after the hour Water Taxi runs rain or shine. Bicycles accommodated, space permitting. Rates subject to change without notice. THAMES RIVER LANDING *Active Military ID required. in Groton: 40 minutes after the hour CHECK OUT OUR The first boat from Groton leaves at 11:40 a.m. on Fridays and 9:40 a.m. on Saturdays and Sundays. MERCHANDISE. Go to our site and click on TRHP Shop. The last stop at Fort Trumbull is 7 p.m. After 7 p.m. the water taxi runs between City Pier, New London and Thames River Landing, Groton every 20 minutes beginning at 7:20 at City Pier. -

Connecticut State Parks System

A Centennial Overview 1913-2013 www.ct.gov/deep/stateparks A State Park Centennial Message from Energy and Environmental Protection Commissioner Robert J. Klee Dear Friends, This year, we are celebrating the Centennial of the Connecticut State Parks system. Marking the 100th anniversary of our parks is a fitting way to pay tribute to past conservation-minded leaders of our state, who had the foresight to begin setting aside important and scenic lands for public access and enjoyment. It is also a perfect moment to commit ourselves to the future of our park system – and to providing first-class outdoor recreation opportunities for our residents and visitors well into the future. Our park system had humble beginnings. A six-member State Park Commission was formed by then Governor Simeon Baldwin in 1913. One year later the Commission purchased its first land, about four acres in Westport for what would become Sherwood Island State Park. Today, thanks to the dedication and commitment of many who have worked in the state park system over the last century, Connecticut boasts a park system of which we can all be proud. This system includes 107 locations, meaning there is a park close to home no matter where you live. Our parks cover more than 32,500 acres and now host more than eight million visitors a year – and have hosted a remarkable total of more than 450 million visitors since we first began counting in 1919. Looking beyond the statistics, our parks offer fantastic opportunities for families to spend time outdoors together. They feature swimming, boating, hiking, picnicking, camping, fishing – or simply the chance to enjoy the world of nature. -

USAMHI Revwar Battles

U.S. Army Military History Institute Revolutionary War-Battles/Places 950 Soldiers Drive Carlisle Barracks, PA 17013-5021 25 Mar 2011 NEW ENGLAND ACTIONS, 1775-81 A Working Bibliography of MHI Sources CONTENTS General Sources…..p. Connecticut…..p.1 Maine…..p.2 Rhode Island…..p.3 Vermont…..p.3 GENERAL SOURCES Barker, Thomas M., and Paul R. Huey. 1776-1777 Northern Campaigns of the American War for Independence and Their Sequel: Contemporary Maps of Mainly German Origin. Vergennes, VT: The Lake Champlain Maritime Museum, 2010. 207 p. E232.B37. Lawrence, Frederick V., Jr. A Journal of Occurrences along the Rebel Coast: A Chronology of Revolutionary War Naval Events in the Waters South and West of Cape Cod, 1775-1781. Westminster, MD: Heritage Books, 2008. 159 p. E271.L39. Melvoin, Richard I. “New England Outpost: War and Society in Colonial Frontier Deerfield, Massachusetts.” PhD dss, MI, 1983. 653 p. F74.D4.M44. CONNECTICUT Burnham, H. E. Battle of Groton Heights: A Story of the Storming of Fort Griswold and the Burning of New London on the Sixth of September, 1781. New London, CT: E. E. Darrow, 1926. 47 p. E241.G8.B87. Cody, Robert M. “The Special Defense and Safety of This Colony: Revolutionary War Actions in Connecticut, 1777-1781.” MA thesis, So CT State, 2000. 103 p. E263.C5.C63. Harris, William W. The Battle of Groton Heights: A Collection of Narratives, Official Reports, Records, Etc., of the Storming of Fort Griswold, the Massacre of its Garrison, and the Burning of New London…. New London, CT: Allyn, 1882. E241.G8.H42. -

Bee Round 1 Bee Round 1 Regulation Questions

NHBB Nationals Bee 2015-2016 Bee Round 1 Bee Round 1 Regulation Questions (1) The speaker of this oration defended his wife by noting that she was born on St. Patrick's Day, and the Irish never quit. A \two-year-old Oldsmobile" and loans from Riggs Bank were recounted in this speech, which was a response to concerns that a fund used to reimburse its speaker for travel expenses was a source of corruption. Its speaker noted that Pat did not have a mink coat, but that his children loved the central figure and would be keeping it. For the point, name this 1952 televised speech by Richard Nixon, named for the cocker spaniel he intended to keep. ANSWER: Checkers speech (accept descriptions of the Nixon Fund speech before \fund" is read) (2) Charles Edwin Fripp's painting of this engagement depicts the 24th Regiment of Foot engaged in hand to hand combat at the foot of a smoke-obscured mountain. Lord Chelmsford's Second and Third Column were overrun in this battle by a “buffalo-horn” formation. Despite winning this battle, Cetshwayo refused to raid Natal in an attempt to prevent war. This battle was immediately followed by another, less successful engagement at Rorke's Drift. For the point, name this 1879 battle in which a British army was decisively defeated by the Zulu. ANSWER: Battle of Isandlwana (3) This writer described \the cold stars lighting, very old and bleak / in different skies" in the poem \I Saw His Round Mouth's Crimson." In one of his poems, the narrator is told \here is no cause to mourn" by a former enemy he meets in Hell. -

National Funding Brochure Final Jan15.Indd

National Battlefield Preservation 2015 Potential Funding Sources 1 www.civilwar.org Table of Contents Introduction 3 Funding for Battlefield Preservation in the United States 5 Federal - Public Funding Sources 11 National - Private Funding Sources 11 Federal/National Public-Private Partnerships 29 Civil War Trust Contacts 31 This material is based upon work assisted by a grant from the Department of the Interior, National Park Service. Any opinions, findings, and conclusions or recommendations expressed in this material are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Department of the Interior. 2 THE CIVIL WAR TRUST Preserving Our Battlefield Heritage Every year, many of our nation’s most important battlefields associated with the Civil War, the American Revolution and the War of 1812 are threatened by uncontrolled development. Preservationists struggle to save these hallowed grounds so that future generations can experience and appreciate the places where the nation’s freedoms were won, expanded, and preserved. The Civil War Trust (the “Trust”) is America’s largest nonprofit organization devoted to the preservation of our nation’s endangered Civil War battlefields. The Trust also promotes educational programs and heritage tourism initiatives to inform the public of the war’s history and the fundamental conflicts that sparked it. To further support our state and local partners, the Trust, through a grant from the National Park Service’s American Battlefield Protection Program (ABPP), have identified a multiplicity of national and state-level funding sources for the preservation of battlefields across the country recognized by the Civil War Sites Advisory Commission and The Report to Congress on the Historic Preservation of Revolutionary War and War of 1812 Sites in the United States.