The Authorship Debate Concerning Lectures on Faith: Exhumation and Reburial

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Moroni: Angel Or Treasure Guardian? 39

Mark Ashurst-McGee: Moroni: Angel or Treasure Guardian? 39 Moroni: Angel or Treasure Guardian? Mark Ashurst-McGee Over the last two decades, historians have reconsidered the origins of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints in the context of the early American tradition of treasure hunting. Well into the nineteenth century there were European Americans hunting for buried wealth. Some believed in treasures that were protected by magic spells or guarded by preternatural beings. Joseph Smith, founding prophet of the Church, had participated in several treasure-hunting expeditions in his youth. The church that he later founded rested to a great degree on his claim that an angel named Moroni had appeared to him in 1823 and showed him the location of an ancient scriptural record akin to the Bible, which was inscribed on metal tablets that looked like gold. After four years, Moroni allowed Smith to recover these “golden plates” and translate their characters into English. It was from Smith’s published translation—the Book of Mormon—that members of the fledgling church became known as “Mormons.” For historians of Mormonism who have treated the golden plates as treasure, Moroni has become a treasure guardian. In this essay, I argue for the historical validity of the traditional understanding of Moroni as an angel. In May of 1985, a letter to the editor of the Salt Lake Tribune posed this question: “In keeping with the true spirit (no pun intended) of historical facts, should not the angel Moroni atop the Mormon Temple be replaced with a white salamander?”1 Of course, the pun was intended. -

Download Ebook / Lectures on Faith

IG1GXEZEDR0E » Kindle # Lectures on Faith Lectures on Faith Filesize: 2.61 MB Reviews I actually started out reading this article ebook. This is for those who statte that there had not been a worth reading. Its been developed in an extremely easy way and it is just after i finished reading this book in which in fact modified me, change the way i really believe. (Antonetta Ritchie IV) DISCLAIMER | DMCA V4RYQF2CYTNK \\ Book // Lectures on Faith LECTURES ON FAITH Createspace, United States, 2013. Paperback. Book Condition: New. 203 x 133 mm. Language: English . Brand New Book ***** Print on Demand *****.The Lectures on Faith were originally prepared as materials for the School of the Prophets in Kirtland, Ohio in 1834 and were included in the Doctrine and Covenants from 1835 to 1921. The preface to the 1835 edition reads as follows: To the members of the church of the Latter Day Saints DEAR BRETHREN: We deem it to be unnecessary to entertain you with a lengthy preface to the following volume, but merely to say, that it contains in short, the leading items of the religion which we have professed to believe. The first part of the book will be found to contain a series of Lectures as delivered before a Theological class in this place [Kirtland, Ohio], and in consequence of their embracing the important doctrine of salvation, we have arranged them into the following work. The second part contains items of principles for the regulation of the church, as taken from the revelations which have been given since its organization, as well as from former ones. -

The Periodical Literature of the Latter Day Saints

Journal of His tory VOL. XIV, No. 3 INDEPENDENCE, MISSOURI JULY, 1921 THE PERIODICAL LITERATURE OF THE LATTER DAY SAINTS BY WALTER W. SMITH The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter Day Saints was little more than a year old when by conference action a monthly periodical was provided for, as indicated by the fol lowing item from the minutes of a conference held at Hiram, Ohio, September, 1831. THE EVENING AND MORNING STAR A conference was held, in which Brother W. W. Phelps was in structed to stop at Cincinnati on his way to Missouri, and purchase a press and type, for the purpose of establishing and publishing a monthly paper at Independence, Jackson County, Missouri, to be called the "Eve ning and Morning Star."-Times and Seasons, vol. 5, p. 481. ·w. W. Phelps, ifl }larmony with the instructions, went to Cincinnati, Ohio, secured the press and type and proceeded to Independence, Jack son County, Missouri, where he issued a prospectus setting forth his in tentions; extracts from which indicate the attitude of Saints relative to the publication of the message of the Restored. Gospel. The Evening and the Morning Star will be published at Independence, Jackson County, State of Missouri. As the forerunner of the night of the end, and the messenger of the day of redemption, the Star will borrow its light from sacred sources, and be devoted to the revelations of God as made known to his servants by the Holy Ghost, at sundry times since the creation of man, but more especially in these last days, for restoration of the house of Israel. -

A Key to Successful Relationships

Religious Educator: Perspectives on the Restored Gospel Volume 7 Number 3 Article 12 9-1-2006 Comprehending the Character of God: A Key to Successful Relationships Kent R. Brooks Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/re BYU ScholarsArchive Citation Brooks, Kent R. "Comprehending the Character of God: A Key to Successful Relationships." Religious Educator: Perspectives on the Restored Gospel 7, no. 3 (2006). https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/re/vol7/ iss3/12 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at BYU ScholarsArchive. It has been accepted for inclusion in Religious Educator: Perspectives on the Restored Gospel by an authorized editor of BYU ScholarsArchive. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. Comprehending the Character of God: A Key to Successful Relationships Kent R. Brooks Kent R. Brooks is an associate professor of Church history and doctrine at BYU. On a beautiful, warm Sunday afternoon in the spring of 1844, the Prophet Joseph Smith delivered the King Follett discourse. Many consider that April 7 general conference address, the last Joseph would give before his martyrdom less than three months later, to be his great- est. The sermon was given in “the groves” surrounding the Nauvoo Temple. Thousands heard the Prophet of the Restoration declare: “It is the first principle of the Gospel to know for a certainty the charac- ter of God, and to know that we may converse with him as one man converses with another.”1 “If men do not comprehend the character of God,” he explained, “they do not comprehend themselves.” They cannot “comprehend anything, either that which is past or that which is to come.” They do not understand their own relationship to God. -

Cowdery, Oliver

Cowdery, Oliver Richard Lloyd Anderson Oliver Cowdery (1806—1850) was next in authority to Joseph Smith in 1830 (D&C 21:10—12), and was a second witness of many critical events in the restoration of the gospel. As one of the three Book of Mormon witnesses, Oliver Cowdery testied that an angel displayed the gold plates and that the voice of God proclaimed them correctly translated. He was with Joseph Smith when John the Baptist restored to them the Aaronic Priesthood and when Peter, James, and John ordained them to the Melchizedek Priesthood and the apostleship, and again during the momentous Kirtland Temple visions (D&C 110). Oliver came from a New England family with strong traditions of patriotism, individuality, learning, and religion. He was born at Wells, Vermont, on October 3, 1806. His younger sister gave the only reliable information about his youth: “Oliver was brought up in Poultney, Rutland County, Vermont, and when he arrived at the age of twenty, he went to the state of New York, where his older brothers were married and settled . Oliver’s occupation was clerking in a store until 1829, when he taught the district school in the town of Manchester” (Lucy Cowdery Young to Andrew Jenson, March 7, 1887, Church Archives). While boarding with Joseph Smith’s parents, he learned of their convictions about the ancient record that their son was again translating after Martin Harris had lost the manuscript in 1828. The young teacher prayed and received answers that Joseph Smith mentioned in a revelation (D&C 6:14—24). -

THE BOOK of MORMON in the ANTEBELLUM POPULAR IMAGINATION by Jared Michael Halverson Thesis Submitted

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by ETD - Electronic Theses & Dissertations “EXTRAVAGANT FICTIONS”: THE BOOK OF MORMON IN THE ANTEBELLUM POPULAR IMAGINATION By Jared Michael Halverson Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of Vanderbilt University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS in Religion August, 2012 Nashville, Tennessee Approved: Professor Kathleen Flake Professor James P. Byrd TABLE OF CONTENTS Chapter I. “A BURLESQUE ON THE BIBLE” . 1 II. “THE ASSAULT OF LAUGHTER” . 9 III. “MUCH SPECULATION”: FIRST IMPRESSIONS OF THE BOOK OF MORMON . 18 IV. ABNER COLE AND THE PALMYRA REFLECTOR . 27 MORE SERIOUS “REFLECTIONS” . 38 V. “BAREFACED FABLING”: THE GOLD BIBLE AS (UN)POPULAR FICTION . 43 “THE YANKEE PEDDLER” . 49 “THE BACKWOODSMAN” . 52 “THE BLACK MINSTREL” . 55 THE “NOVEL” BOOK OF MORMON . 59 VI. A RHETORIC OF RIDICULE . 64 ALEXANDER CAMPBELL . 67 EBER HOWE . 70 ORIGEN BACHELER . 74 POPULAR POLEMICS . 78 VII. CONCLUSION: THE LAST LAUGH . 84 BIBLIOGRAPHY . 92 ii CHAPTER 1 “A BURLESQUE ON THE BIBLE” Sometime in late August or early September, 1831, Robert Dale Owen, son of the Scottish utopian reformer Robert Owen, received a letter from his brother William, who had hurriedly written from an Erie Canal boat somewhere near Syracuse, New York. Just as hastily Robert published the correspondence in his New York City newspaper, the Free Enquirer, not knowing that he would receive another, longer letter from William within days, just in time to be included in his weekly’s next run. What proved to be so pressing was what William had discovered onboard the canal boat: “I have met,” he announced dramatically, “with the famous ‘Book of Mormon.’”1 Published in 1830, the Book of Mormon claimed to be nothing short of scripture, an account of America’s ancient inhabitants (themselves a scattered Hebrew remnant) and God’s dealings with them over a long and bloody history. -

Elohim and Jehovah in Mormonism and the Bible

Elohim and Jehovah in Mormonism and the Bible Boyd Kirkland urrently, the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints defines the CGodhead as consisting of three separate and distinct personages or Gods: Elohim, or God the Father; Jehovah, or Jesus Christ, the Son of God both in the spirit and in the flesh; and the Holy Ghost. The Father and the Son have physical, resurrected bodies of flesh and bone, but the Holy Ghost is a spirit personage. Jesus' title of Jehovah reflects his pre-existent role as God of the Old Testament. These definitions took official form in "The Father and the Son: A Doctrinal Exposition by the First Presidency and the Twelve" (1916) as the culmination of five major stages of theological development in Church history (Kirkland 1984): 1. Joseph Smith, Mormonism's founder, originally spoke and wrote about God in terms practically indistinguishable from then-current protestant the- ology. He used the roles, personalities, and titles of the Father and the Son interchangeably in a manner implying that he believed in only one God who manifested himself as three persons. The Book of Mormon, revelations in the Doctrine and Covenants prior to 1835, and Smith's 1832 account of his First Vision all reflect "trinitarian" perceptions. He did not use the title Elohim at all in this early stage and used Jehovah only rarely as the name of the "one" God. 2. The 1835 Lectures on Faith and Smith's official 1838 account of his First Vision both emphasized the complete separateness of the Father and the Son. -

The Old Testament the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-Day Saints

A Supplement to the Gospel Doctrine Manual The Old Testament The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints Lesson 1 “This Is My Work and My Glory” Moses 1 Purpose: To understand that (1) we are children of God, (2) we can resist Satan’s temptations, and (3) God’s work and glory is to bring to pass our immortality and eternal life. The gospel of Jesus Christ is the plan of salvation. It enables man to regenerate his life from the fallen state of mortality to become a spiritual being, becoming a new creature in Christ (II Cor 5:17) and have His image engraven in your countenance (Alma 5:19) while in mortality and throughout the eternities. It contains the principles and ordinances that adopt us into the family Christ and obtain a fullness of His glory. (D&C Sec. 98). Those principles and ordinances are divided into two parts, first is what the Lord called the ‘preparatory gospel’ (D&C Sec. 84:26 ) consisting of 1, Faith in the Lord, Jesus Christ, 2 Repentance, and 3 Baptism by immersion for the remission of sins. These steps prepare us for the gospel which is receiving the Holy Ghost by the laying on hands by those in authority to administer that ordinance. Having the Holy Ghost in your life is having the gospel in your life, there is no other definition in the scriptures. The scriptures are instructions on how to receive and keep the Holy Ghost in our lives and examples of those that did and those that did not. -

The Quest for Religious Authority and the Rise of Mormonism.” Dialogue: a Journal of Mormon Thought, Vol

Mario S De Pillis, “The Quest for Religious Authority and the Rise of Mormonism.” Dialogue: A Journal of Mormon Thought, Vol. 1 No. 1 (1966): 68–88. Copyright © 2012 Dialogue Foundation. All Rights Reserved THE QUEST FOR RELIGIOUS AUTHORITY AND THE RISE OF MORMONISM by Mario S. De Pillis The editors believe this essay will help bridge the unfortunate gulf between Mormon and non-Mormon writers of Mormon history, which has allowed Mormons to be cut off from many useful insights and allowed non-Mormons to be blind to important elements such as the role of doctrine. Mario De Pillis teaches American social history and the American West at the University of Massachusetts. He has been trustee and historical consultant for the restor- ation of the Shaker community of Hancock, Massachusetts, and is presently the Roman Catholic member of a four-college ecumenical seminar of Protestant and Roman Catholic clergy and laity. Both Mormon and non-Mormon re- sponses have been arranged for the next issue. IF THERE IS TO BE ANY HONEST DIALOGUE WHATSOEVER BETWEEN educated members of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (Mormons) and outsiders, the question of the historical origins of Mormonism must ever remain central. And in a way it has remained central. Nevertheless, no serious student of writings on the origins of this central issue can deny that the controversial "dialogue" of the past hundred and thirty-five years has been less than candid. It has long been true, however unfortunate loyal Mormons may find it, that the historians who write our generally accepted social and intel- lectual history have rarely consulted such standard Mormon his- torians as B. -

The Role and Function of the Seventies in LDS Church History

Brigham Young University BYU ScholarsArchive Theses and Dissertations 1960 The Role and Function of the Seventies in LDS Church History James N. Baumgarten Brigham Young University - Provo Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/etd Part of the Cultural History Commons, and the Mormon Studies Commons BYU ScholarsArchive Citation Baumgarten, James N., "The Role and Function of the Seventies in LDS Church History" (1960). Theses and Dissertations. 4513. https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/etd/4513 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by BYU ScholarsArchive. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of BYU ScholarsArchive. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. 3 e F tebeebTHB ROLEROLB ardaindANDAIRD FUNCTION OF tebeebTHB SEVKMTIBS IN LJSlasLDS chweceweCHMECHURCH HISTORYWIRY A thesis presentedsenteddented to the dedepartmentA nt of history brigham youngyouyom university in partial ftlfillmeutrulfilliaent of the requirements for the degree master of arts by jalejamsjamejames N baumgartenbelbexbaxaartgart9arten august 1960 TABLE CFOF CcontentsCOBTEHTS part I1 introductionductionreductionroductionro and theology chapter bagragpag ieI1 introduction explanationN ionlon of priesthood and revrevelationlation Sutsukstatementement of problem position of the writer dedelimitationitationcitation of thesis method of procedure and sources II11 church doctrine on the seventies 8 ancient origins the revelation -

Claremont Mormon Studies J Newsletteri

Claremont Mormon Studies j NEWSLETTERi SPRING 2013 t ISSUE NO. 8 Thoughts from the IN THIS ISSUE Hunter Chair Perfecting Mormons & Mormon Studies at BY Patrick Q. Mason Claremont Howard W. Hunter Chair of Mormon Studies iPAGE 2 k he Mormon moment may be University is fond of saying, the Student Contributions over, but Mormon studies is research university is one of T PAGE 3 alive and well. With the election humankind’s greatest inventions— k past us, media and popular attention and graduate school is, at its about Latter-day Saints will wane best, the most refined version of Oral Histories Archived at considerably, but that incomparable Honnold-Mudd PAGE 7 there has never been “When we get it right, invention. a more auspicious When we get k time for the graduate education it right, graduate “Martyrs and Villains” scholarly study of has been and remains education has been PAGE 8 Mormonism. a tremendous force for and remains a k We live in an era the advancement of tremendous force for Reminiscence at of mass media and the advancement of human knowledge.” the Culmination of social technologies human knowledge. Coursework that allow us to Mormon Studies at PAGE 8 “connect” with thousands, even CGU is just one slice of that grand millions, of people at the click of a endeavor; Steve Bradford’s insightful few buttons. We are witnessing a column that follows reminds us revolution in the way that higher of some of the reasons why the education is being delivered, and it endeavor is worthy of not only will be fascinating to see what will our enthusiasm but our support as happen with developments such well. -

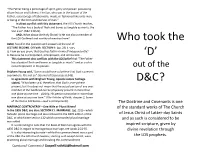

Who Took the D out of the D&C.Pdf

“The Father being a personage of spirit, glory and power: possessing all perfection and fullness: The Son, who was in the bosom of the Father, a personage of tabernacle, made, or fashioned like unto man, or being in the form and likeness of man.” In direct conflict with this statement, the LDS Church teaches, “The Father has a body of flesh and bones as tangible as man’s; the Son also” (D&C 130:22). AND, What about the Holy Ghost? Is He not also a member of the LDS Godhead and worthy of mention here? Who took the ALSO, found in the question and answers at the end of LECTURE SECOND. Of Faith. SECTION II. (pg. 26) it says, Q. How do you prove that God has faith in himself independently? A. Because he is omnipotent, omnipresent, and omniscient… ‘D’ This statement also conflicts with the LDS belief that “The Father has a body of flesh and bones as tangible as man’s” and as such is not omnipresent in His person. out of the Brigham Young said, "Some would have us believe that God is present everywhere. It is not so" (Journal of Discourses 6:345). In agreement with Brigham Young, Apostle James Talmage D&C ? stated, “It has been said, therefore, that God is everywhere present; but this does not mean that the actual person of any one member of the Godhead can be physically present in more than one place at one time… plainly, His person cannot be in more than one place at any one time.” (The Articles of Faith, chapter 2, Some of the Divine Attributes—God is Omnipresent).