What Makes Finzi Finzi? the Convergence of Style and Struggle in the Life of Gerald Finzi and in His Set Before and After Summer, Op

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Michael Hurd

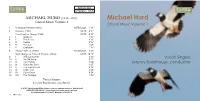

SRCD.363 STEREO DDD MICHAEL HURD (1928- 2006) Michael Hurd Choral Music Volume 1 Choral Music Volume 1 1 (1987) SATB/organ 7’54” 2 (1987) SATB 6’07” (1996) SATB 9’55” 3 I Antiphon 1’03” 4 II The Pulley 3’13” 5 III Vertue 2’47” 6 IV The Call 1’05” 7 V Exultation 1’47” 8 (1987) SATB/organ 3’00” (1994) SATB 20’14” 9 I Will you Come? 2’00” Vasari Singers 10 II An Old Song 3’12” 11 III Two Pewits 2’06” Jeremy Backhouse, conductor 12 IV Out in the Dark 3’07” 13 V The Dark Forest 2’28” 14 VI Lights Out 4’28” 15 VII Cock-Crow 0’54” 16 VIII The Trumpet 1’59” Vasari Singers Jeremy Backhouse, conductor c © 20 SRCD.363 SRCD.363 1 Michael Hurd was born in Gloucester on 19 December 1928, the son of a self- (1966) SSA/organ 11’14” employed cabinetmaker and upholsterer. His early education took place at Crypt 17 I Kyrie eleison 1’39” Grammar School in Gloucester. National Service with the Intelligence Corps involved 18 II Gloria in excelsis Deo 3’17” a posting to Vienna, where he developed a burgeoning passion for opera. He studied 19 III Sanctus 1’35” at Pembroke College, Oxford (1950-53) with Sir Thomas Armstrong and Dr Bernard 20 IV Benedictus 1’40” Rose and became President of the University Music Society. In addition, he took 21 V Agnus Dei 3’03” composition lessons from Lennox Berkeley, whose Gallic sensibility may be said to have (1980) SATB 5’39” influenced Hurd’s own musical language, not least in the attractive and witty Concerto 22 I Captivity 2’34” da Camera for oboe and small orchestra (1979), which he described in his programme 23 II Rejection 1’03” note as a homage to Poulenc’s ‘particular genius’. -

Saken Bergaliyev Matr.Nr. 61800203 Benjamin Britten Lachrymae

Saken Bergaliyev Matr.Nr. 61800203 Benjamin Britten Lachrymae: Reflections on a Song of Dowland for viola and piano- reflections or variations? Master thesis For obtaining the academic degree Master of Arts of course Solo Performance Viola in Anton Bruckner Privatuniversität Linz Supervised by: Univ.Doz, Dr. M.A. Hans Georg Nicklaus and Mag. Predrag Katanic Linz, April 2019 CONTENT Foreword………………………………………………………………………………..2 CHAPTER 1………………………………...………………………………….……....6 1.1 Benjamin Britten - life, creativity, and the role of the viola in his life……..…..…..6 1.2 Alderburgh Festival……………………………......................................................14 CHAPTER 2…………………………………………………………………………...19 John Dowland and his Lachrymae……………………………….…………………….19 CHAPTER 3. The Lachrymae of Benjamin Britten.……..……………………………25 3.1 Lachrymae and Nocturnal……………………………………………………….....25 3.2 Structure of Lachrymae…………………………………………………………....28 Conclusion……………………………………………………………………………..39 Bibliography……………………………………….......................................................43 Affidavit………………………………………………………………………………..45 Appendix ……………………………………………………………………………....46 1 FOREWORD The oeuvre of the great English composer Benjamin Britten belongs to one of the most sig- nificant pages of the history of 20th-century music. In Europe, performers and the general public alike continue to exhibit a steady interest in the composer decades after his death. Even now, the heritage of the master has great repertoire potential given that the number of his written works is on par with composers such as S. Prokofiev, F. Poulenc, D. Shostako- vich, etc. The significance of this figure for researchers including D. Mitchell, C. Palmer, F. Rupprecht, A. Whittall, F. Reed, L. Walker, N. Abels and others, who continue to turn to various areas of his work, is not exhausted. Britten nature as a composer was determined by two main constants: poetry and music. In- deed, his art is inextricably linked with the word. -

Finzi Bagatelles

Gerald Finzi (1901-1956): Five Bagatelles for clarinet and piano, Opus 23 (1945) Prelude: Allegro deciso Romance: Andante tranquillo Carol: Andante semplice Forlana: Allegretto grazioso Fughetta: Allegro vivace Better known for his vocal music, Finzi also wrote well for the clarinet: these Five Bagatelles and his later Clarinet Concerto are frequently played. Born to a German/Italian Jewish family in London, the teenage Finzi was taught composition in Harrogate by Ernest Farrar, a pupil of Stanford, and by Edward Bairstow, Master of Music at York Minster. His subsequent friends and colleagues included Vaughan Williams, R.O.Morris, Holst, Bliss, Rubbra and Howard Ferguson; his music is firmly within this English tradition. He was attracted to the beauty of the English countryside and to the poetry of Traherne, Hardy and Christina Rosetti. The Five Bagatelles had a tortuous birth. In the summer of 1941, increasingly confident in his powers as a composer, Finzi completed three character pieces for clarinet and piano before being drafted into the Ministry of War Transport. He used “20-year-old bits and pieces”, which he had been working on since 1938. A fourth was added in January 1942 and the whole group performed at a wartime National Gallery lunchtime concert. Leslie Boosey wanted to publish the pieces separately, but in July 1945 Finzi persuaded him to publish them as a group, together with an additional fast finale. Somewhat to Finzi's chagrin, they became his most popular piece: ‘they are only trifles... not worth much, but got better notices than my decent stuff’. The first movement shows Bach's influence on Finzi and contains a slow central section with characteristically wistful falling minor 7ths. -

Music at Grace 2016-2017

Music at Grace 2016-2017 WELCOME Dear Friends, We are delighted to welcome you to this season of Music at Grace! The coming year continues our tradition of offering glorious sacred choral music at the Sunday Eucharist, Evensong, Lessons and Carols, and in concert. In addition, we are thrilled to announce the debut of Collegium Ancora: Rhode Island’s Professional Chamber Choir, Ensemble-in-Residence at Grace Church. We also welcome the Brown University Chorus and Schola Cantorum of Boston to Grace on April 7 for a gala concert performance of Bach’s monumental St. Matthew Passion. And our Thursdays at Noon concert series resumes in September! This booklet outlines the musical offering for the coming season, particularly the 10 AM Holy Eucharist on Sunday mornings. Also included is an envelope for your support of Music at Grace. Whether you are a parishioner or a friend of music, we hope you will consider making a donation to support our musical presence in Downcity Providence, for the worship or concert setting. A return envelope is enclosed for your convenience, and names listed will be included in the programs for special services and concerts. We wish to remind parishioners of Grace church that any gift made to Music at Grace should be in addition to your regular Stewardship pledge which is so important to the church. We hope that you will walk through our historic doors on Westminster Street in downtown Providence for worship or concert, or both very soon! The Reverend Canon Jonathan Huyck+ Rector Vincent Edwards Director of Music MUSIC -

Crisis and Catharsis: Linear Analysis and the Interpretation of Herbert

CRISIS AND CATHARSIS: LINEAR ANALYSIS AND THE INTERPRETATION OF HERBERT HOWELLS’ REQUIEM AND HYMNUS PARADISI Jennifer Tish Davenport Dissertation Prepared for the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY UNIVERSITY OF NORTH TEXAS August 201 8 APPROVED: Timothy L. Jackson, Major Professor Stephen Slottow, Committee Member Diego Cubero, Committee Member Allen Hightower, Committee Member Benjamin Brand, Director of Graduate Studies in the College of Music John W. Richmond, Dean of the College of Music Victor Prybutok, Dean of the Toulouse Graduate School Davenport, Jennifer Tish. Crisis and Catharsis: Linear Analysis and the Interpretation of Herbert Howells’ “Requiem” and “Hymnus Paradisi.” Doctor of Philosophy (Music), August 2018, 365 pp., 19 tables, 147 musical examples, bibliography, 58 titles. Hymnus Paradisi (1938), a large-scale choral and orchestral work, is well-known as an elegiac masterpiece written by Herbert Howells in response to the sudden loss of his young son in 1935. The composition of this work, as noted by the composer himself and those close to him, successfully served as a means of working through his grief during the difficult years that followed Michael's death. In this dissertation, I provide linear analyses for Howells' Hymnus Paradisi as well as its predecessor, Howells' Requiem (1932), which was adapted and greatly expanded in the creation of Hymnus Paradisi. These analyses and accompanying explanations are intended to provide insight into the intricate contrapuntal style in which Howells writes, showing that an often complex musical surface is underpinned by traditional linear and harmonic patterns on the deeper structural levels. In addition to examining the middleground and background structural levels within each movement, I also demonstrate how Howells creates large- scale musical continuity and shapes the overall composition through the use of large- scale linear connections, shown through the meta-Ursatz (an Ursatz which extends across multiple movements creating multi-movement unity). -

The Ivor Gurney Society Newsletter

THE IVOR GURNEY SOCIETY NEWSLETTER NUMBER 59 February 2016 Spring Weekend 2016, 7-8 May 2016 Gurney and Blunden The Spring Weekend 2016 event features a talk and discussion led by the author, poet and WW1 expert John Greening, and by Margi Blunden. They will talk about Edmund Blunden (Margi’s father), who knew Gurney and was his first editor. John Greening recently produced a beautiful new edition of Blunden's Undertones of War for OUP. There will also be a display of Blunden items. Later there will be a recital by Midori Komachi (violin) and Simon Callaghan of British Music, to include Gurney and Vaughan Williams's 'The Lark Ascending'. Final programme to be confirmed, but may also include Holst and Delius. Saturday 7th May events will take place at St Andrew’s Church Centre, Station Road, Churchdown, Gloucester GL3 2JT. To book a place, please complete and return the enclosed form to Colin Brookes, Treasurer. Programme for 7 May: (11.00 am Doors open) 12.00 noon Annual General Meeting 12.30 pm Lunch 1.30 pm Talk and discussion led by John Greening and Margi Blunden 2.30 pm Break 3.00 pm Recital by Midori Konachi accompanied by Simon Callaghan Those attending should bring a packed lunch. Coffee, tea and soft drinks will be available. 8 May - Cranham: Poetry Walk (see p.2) Edmund Blunden ‘Remembering always my dear Cranham’ Sunday Morning Walk, May 8 Where Cooper’s stands by 2016 10.30am Cranham, ‘Remembering always my dear Where the hill gashes white Cranham’ is a phrase from a Shows golden in the sunshine, letter sent by Gurney to Herbert Our sunshine, God’s delight. -

Copyright 2014 Renée Chérie Clark

Copyright 2014 Renée Chérie Clark ASPECTS OF NATIONAL IDENTITY IN THE ART SONGS OF RALPH VAUGHAN WILLIAMS BEFORE THE GREAT WAR BY RENÉE CHÉRIE CLARK DISSERTATION Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Musicology in the Graduate College of the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, 2014 Urbana, Illinois Doctoral Committee: Associate Professor Christina Bashford, Chair Associate Professor Gayle Sherwood Magee Professor Emeritus Herbert Kellman Professor Emeritus Chester L. Alwes ABSTRACT This dissertation explores how the art songs of English composer Ralph Vaughan Williams (1872-1958) composed before the Great War expressed the composer’s vision of “Englishness” or “English national identity”. These terms can be defined as the popular national consciousness of the English people. It is something that demands continual reassessment because it is constantly changing. Thus, this study takes into account two key areas of investigation. The first comprises the poets and texts set by the composer during the time in question. The second consists of an exploration of the cultural history of British and specifically English ideas surrounding pastoralism, ruralism, the trope of wandering in the countryside, and the rural landscape as an escape from the city. This dissertation unfolds as follows. The Introduction surveys the literature on Vaughan Williams and his songs in particular on the one hand, and on the other it surveys a necessarily selective portion of the vast literature of English national identity. The introduction also explains the methodology applied in the following chapters in analyzing the music as readings of texts. The remaining chapters progress in the chronological order of Vaughan Williams’s career as a composer. -

Durham Research Online

Durham Research Online Deposited in DRO: 07 March 2016 Version of attached le: Published Version Peer-review status of attached le: Peer-reviewed Citation for published item: Dibble, Jeremy (2015) 'War, impression, sound, and memory : British music and the First World War.', German Historical Institute London bulletin., 37 (1). pp. 43-56. Further information on publisher's website: http://www.ghil.ac.uk/publications/bulletin/bulletin371.html Publisher's copyright statement: Additional information: Use policy The full-text may be used and/or reproduced, and given to third parties in any format or medium, without prior permission or charge, for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-prot purposes provided that: • a full bibliographic reference is made to the original source • a link is made to the metadata record in DRO • the full-text is not changed in any way The full-text must not be sold in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. Please consult the full DRO policy for further details. Durham University Library, Stockton Road, Durham DH1 3LY, United Kingdom Tel : +44 (0)191 334 3042 | Fax : +44 (0)191 334 2971 https://dro.dur.ac.uk German Historical Institute London BULLETIN ISSN 0269-8552 Jeremy C. Dibble: War, Impression, Sound, and Memory: British Music and the First World War German Historical Institute London Bulletin, Vol 37, No. 1 (May 2015), pp43-56 WAR, IMPRESSION, SOUND, AND MEMORY: BRITISH MUSIC AND THE FIRST WORLD WAR JEREMY C. D IBBLE The First World War had a profound effect upon British music. -

THE ENGLISH MUSICAL RENAISSANCE and ITS INFLUENCE on GERALD FINZI: an in DEPTH STUDY of TILL EARTH OUTWEARS, OP. 19A

2 THE ENGLISH MUSICAL RENAISSANCE AND ITS INFLUENCE ON GERALD FINZI: AN IN DEPTH STUDY OF TILL EARTH OUTWEARS, OP. 19a A thesis submitted to the Miami University Honors Program in partial fulfillment of the requirements for University Honors with Distinction by Sean Patrick Lair, B.M., B.A. May 2009 Oxford, Ohio 3 ABSTRACT THE ENGLISH MUSICAL RENAISSANCE AND ITS INFLUENCE ON GERALD FINZI: AN IN DEPTH STUDY OF TILL EARTH OUTWEARS, OP. 19a By Sean Patrick Lair, B.M., B.A. Gerald Finzi (1901-1956) was an early Twentieth Century, British composer, whose talent is most notable in the realm of art song. Seeing as his works so perfectly suit my voice, I have decided to sing a song set of his on my senior recital, entitled Till Earth Outwears, Op. 19a. Through research, I wish to better inform my performance, and the future ones of others, by better acquainting myself with his life and compositional techniques, most assuredly shaped by what has always been a very distinct British aesthetic. His models and colleagues, including composers like Ralph Vaughan Williams, Roger Quilter, and John Ireland, reinvigorated the English musical culture and elevated the British standing on the world music scene at the end of the nineteenth century and beginning of the twentieth century. By studying this music in such minute detail, the proper method of performance can be decided and musical decisions will be better informed. Issues like breathing, phrasing, and tempo fluctuations or rubato can be addressed. I wish to expand the knowledge of the art song of Gerald Finzi, which, while not unknown, is markedly seldom performed. -

A Lament While Serving with the Alongside Poems by Walt Whitman

WORLD WORLD Ivor Gurney Gurney's experience of - it’s not really lambkins frisking at that “the German people are fighting for a just the war was marred bya all as most people take for granted”. cause”. He was amused by the thought of series of injuries, including “Dona nobis Pacem”, written in 1936, musicians becoming soldiers. “Bach as a staff- being shot in the shoulder echoes Bliss in using Christian texts sergeant (handing over a pair of oversized A lament while serving with the alongside poems by Walt Whitman. boots), that would be okay, but Beethoven Gloucestershire Regiment There is no doubt that in this work, practicing rifle drill, Mozart throwing hand- in April 1917, and gassed FOR THE LOST in September that same Vaughan Williams was cautioning grenades or standing guard year. Some have against conflict. in front of a barracks; Schubert as an air force Like the artists, poets and writers of the era, the world was also robbed of speculated this may have The Great War was a tragedy for lieutenant and Mendelssohn as an NCO at a many of its brightest musical talents. Stephen Johns, Artistic Director at the had an impact on the British artists, no doubt, but there vehicle fleet convoy? They are inconceivable.” severity of his shell-shock were similar losses on all sides of As the war moved on, including the death in Royal College of Music, looks back at the composers who were lost during the after the war. the conflict. The German composer, action of his father, he came ever closer to the First World War, and those whose experiences informed their later works Rudi Stephan is worthy of front and its horrors. -

Journal of the YDOA March Edition

The PipeLine Journal of the YDOA March Edition Patron: Dr Francis Jackson CBE (Organist Emeritus, York Minster) President: Nigel Holdsworth, 01904 640520 Secretary: Renate Sangwine, 01904 781387 Treasurer: Cynthia Wood, 01904 795204 Membership Secretary: Helen Roberts, 01904 708625 The PipeLine Editor, Webmaster and YDOA Archivist: Maximillian Elliott www.ydoa.co.uk The York & District Organists’ Association is affiliated to the Incorporated Association of Organists (IAO) and serves all who are interested in the organ and its music. Contents 1. Introduction ................................................................................ 3 2. YDOA Events ............................................................................... 4 3. The Ebor Organ Album……………………………………………… ............... 5 4. Previous Event ............................................................................ 6 5. Next Event ................................................................................... 8 6. Upcoming Recitals & Concerts…………………………………………………. 9 7. Gallery ....................................................................................... 12 8. Article I ...................................................................................... 13 9. Article II ..................................................................................... 14 10. Article III ................................................................................... 28 11. Organ of the Month .................................................................. 30 12. -

What Sweeter Music: an English Christmas

What Sweeter Music Performed In December of 1843 Charles Dickens dashed off a short seasonal book in the hope of making some quick money. A Christmas Carol became an instant success and its characters and story quickly passed into the public domain. In 1871 Sir John Stainer published his anthology Christmas Carols Old and New, which rapidly became the standard versions and harmonizations used by succeeding generations to this day. It is little wonder that when we think of Christmas, Victorian traditions inevitably spring to mind. What Sweeter Music celebrates the rich musical heritage of an English Christmas. This year marks the centenary of the birth of Gerald Finzi, one of the most English of all English composers. He was part of a remarkable renaissance in English music which began toward the end of the nineteenth century and included composers such as Finzi's contemporaries Gustav Holst, Benjamin Britten and Peter Warlock, all of whom are represented on this program. He was born into a wealthy family and for the most part never had to worry about having to make a living, but that did not shield him from personal tragedy. His father died when he was seven and before he was eighteen he experienced the death of all three older brothers and his first music teacher, Edward Farrar, who had enlisted and died in the war. Finzi was a solitary, introspective child and an indifferent student, once remaining in the same grade at one school for four years and feigning fainting spells to be sent home from another. Ironically, Finzi was to become perhaps the most literary of all composers.