Shuja-Ud-Daulah

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Download (2216Kb)

A Thesis Submitted for the Degree of PhD at the University of Warwick Permanent WRAP URL: http://wrap.warwick.ac.uk/150023 Copyright and reuse: This thesis is made available online and is protected by original copyright. Please scroll down to view the document itself. Please refer to the repository record for this item for information to help you to cite it. Our policy information is available from the repository home page. For more information, please contact the WRAP Team at: [email protected] warwick.ac.uk/lib-publications ‘AN ENDLESS VARIETY OF FORMS AND PROPORTIONS’: INDIAN INFLUENCE ON BRITISH GARDENS AND GARDEN BUILDINGS, c.1760-c.1865 Two Volumes: Volume I Text Diane Evelyn Trenchard James A thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Warwick, Department of History of Art September, 2019 Table of Contents Acknowledgements ………………………………………………………………. iv Abstract …………………………………………………………………………… vi Abbreviations ……………………………………………………………………. viii . Glossary of Indian Terms ……………………………………………………....... ix List of Illustrations ……………………………………………………………... xvii Introduction ……………………………………………………………………….. 1 1. Chapter 1: Country Estates and the Politics of the Nabob ………................ 30 Case Study 1: The Indian and British Mansions and Experimental Gardens of Warren Hastings, Governor-General of Bengal …………………………………… 48 Case Study 2: Innovations and improvements established by Sir Hector Munro, Royal, Bengal, and Madras Armies, on the Novar Estate, Inverness, Scotland …… 74 Case Study 3: Sir William Paxton’s Garden Houses in Calcutta, and his Pleasure Garden at Middleton Hall, Llanarthne, South Wales ……………………………… 91 2. Chapter 2: The Indian Experience: Engagement with Indian Art and Religion ……………………………………………………………………….. 117 Case Study 4: A Fairy Palace in Devon: Redcliffe Towers built by Colonel Robert Smith, Bengal Engineers ……………………………………………………..…. -

In the Name of Krishna: the Cultural Landscape of a North Indian Pilgrimage Town

In the Name of Krishna: The Cultural Landscape of a North Indian Pilgrimage Town A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF THE UNIVERSITY OF MINNESOTA BY Sugata Ray IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Frederick M. Asher, Advisor April 2012 © Sugata Ray 2012 Acknowledgements They say writing a dissertation is a lonely and arduous task. But, I am fortunate to have found friends, colleagues, and mentors who have inspired me to make this laborious task far from arduous. It was Frederick M. Asher, my advisor, who inspired me to turn to places where art historians do not usually venture. The temple city of Khajuraho is not just the exquisite 11th-century temples at the site. Rather, the 11th-century temples are part of a larger visuality that extends to contemporary civic monuments in the city center, Rick suggested in the first class that I took with him. I learnt to move across time and space. To understand modern Vrindavan, one would have to look at its Mughal past; to understand temple architecture, one would have to look for rebellions in the colonial archive. Catherine B. Asher gave me the gift of the Mughal world – a world that I only barely knew before I met her. Today, I speak of the Islamicate world of colonial Vrindavan. Cathy walked me through Mughal mosques, tombs, and gardens on many cold wintry days in Minneapolis and on a hot summer day in Sasaram, Bihar. The Islamicate Krishna in my dissertation thus came into being. -

Medieval Banaras: a City of Cultural and Economic Dynamics and Response

[VOLUME 5 I ISSUE 4 I OCT. – DEC. 2018] e ISSN 2348 –1269, Print ISSN 2349-5138 http://ijrar.com/ Cosmos Impact Factor 4.236 Medieval Banaras: A City of Cultural and Economic Dynamics and Response Pritam Kumar Gupta Research Scholar, Jawaharlal Nehru University. Received: November 12, 2018 Accepted: December 17, 2018 ABSTRACT This paper attempts to understand the cultural and economic importance of the city of Banarasto various medieval political powers.As there are many examples on the basis of which it can be said that the nature, dynamics, and popularity of a city have changed at different times according to the demands and needs of the time. Banaras is one of those ancient cities which has been associated with various religious beliefs and cultures since ancient times but the city, while retaining its old features, established itself as a developed trade city by accepting new economic challenges, how the Banaras provided a suitable environment to the changing cultural and economic challenges, whereas it went through the pressure of different political powers from time to time and made them realize its importance. This paper attempts to understand those suitable environmentson how the landscape of Banaras and its dynamics in the medieval period transformed this city into a developed economic-cultural city. Keywords: Banaras, Religious, Economic, Urbanization, Mughal, Market, Landscape. Wide-ranging literary works have been written on Banaras by scholars of various subject backgrounds, in which they highlight the socio-economic life of different religious and cultural ideals of the inhabitants of Banaras. It is very important for scholars studying regional history to understand what challenges a city has to face in different historical periods to maintain its identity.The name Banaras is found as the present name Varanasi in the Buddhist Jataka and Hindu epic Mahabharata. -

District Census Handbook, 12-Bareiliy, Uttar Pradesh

CENSUS 1961 DISTRICT CENSUS HANDBOOK_ UTTA,R PRAD.ESH 12~-BAREILL Y ,DISTRICT ~QCKNOW: ~intendel1~, Printing and Stationery, U. P. (India) 1965 N DISTRICT BAREILLY ·x DI5IIIICT HEADQUMTIEAS w-. IEMJQIIMITEJIS IlDQ( IEMQUMlTERS ...-.cT 8DUIII:WW w-. IOIN;IIIiIR't RIX UIE wnH 51JII1ON (BGJ RIX UIIE WI114 51JII1ON(1Iil&) 1MJ1QNM.. SWE_ LOQL ROIItoD ME1lILLED IDCM.. ROIItoD INE1lU..L£D RIWR CMW.. ~HOU5E POUCE~ ~OFI'JCE ~.~OFFICE ~ f DISPEIISM\' I I i , ~~ 5 10 15 aD 1a.I I ft.LAIIiIE OWR 1000 POR 76d 7I/IJttI E &.P.... ......... ...., .......................... .....,.. ........ .... -II _ , • _ CIPIIIIIf_·· .. , CONTENTS Page. Preface I Introduction liT I-CENSUS TABLES A-GENERAL POPULATION TABLES A-I Area, Houses and Population 5 Appendix I-Statement showing 1951 Territorial Units constituting the present' 1961 set~~p c;f. th~ District 6 Appendix II-Number of Villages with a Population of 5,000 and over and Towns with a Population under 5,000 6 Appendix Ill-Houseless and Institutional Population 7 A-II Variation in Population during Sixty Years 8 Appendix 1951 Population according to the territorial jurisdiction in 1951 and changes in_ area and popUlation involved in those changes 8 A-III Villages classified by Population 9 A;_IV' Towns (and Town Groups) classified by Population in 1961 with Variation since 1941 18 B-GENERAL ECONOMIC TABLES B-1 & II Workers and Non-workers in District and Towns classified by Sex and broad Age-groups 14 Part A-Industrial Classification of Workers and Non-workers by Educational J;..evels in Urban AFeas only 22 Part B-Industrial Classification of Workers and Non-worken by Educational Levels in Rural Areas only 24 B-IV Part A-Industrial Classification by Sex and Class of Worker of Persons lilt Work at Household Industry 28 Part B-Industrihl Classification by Sex and Class of Worker of Persons at Work in Non-household Industry, Trade, Business, Profession or Service 32 Part C-Industrial Classification by Sex and Divisions, Major Groups and Minor Groups of Persons at Work other than Cultivation 40 Part C:_. -

(Electrical) 663 12

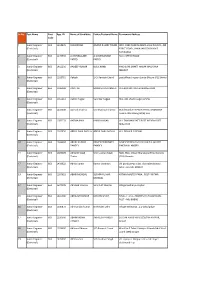

Sr.No. Post Name Post App. ID Name of Candidate Father/Husband Name Permanent Address Code 1 Junior Engineer 663 1244445 8430000362 ANAND BIHARI TIWARI HNO. 1880 NEAR SHARMA HIGH SCHOOL, AIR (Electrical) FORCE ROAD , JAWAHAR COLONY NIT FARIDABAD 2 Junior Engineer 663 1249993 A GOPIBALLABH A GOURISANKAR N.A.C OFFICE ROAD (Electrical) PATRO PATRO 3 Junior Engineer 663 1412230 AADEEP KUMAR DULICHAND H NO 1046 SHAKTI NAGAR MALIYANA (Electrical) MEERUT 4 Junior Engineer 663 1318751 Aakash S/O: Ramesh Chand post office chirgaon Sunda Bhoura (41) Shimla (Electrical) 5 Junior Engineer 663 1466968 AAKIL ALI MOHD ZAFAR AHMED VILL-RAJPUR POST-GARHMEERPUR (Electrical) 6 Junior Engineer 663 1561212 Aakriti Nagpal Varinder Nagpal Hno. 434 shastri nagar jammu (Electrical) 7 Junior Engineer 663 1416308 Aashish Sharma S/O Shadi Lal Sharma Ward-Number-5 POST OFFICE GHANGRET (Electrical) TEHSIL AMB Ghangret (8) Una 8 Junior Engineer 663 1587233 AATMA RAM HARISHANKAR VILL TAMMAN PATTI POST MENDIA DIST (Electrical) MIRZAPUR 9 Junior Engineer 663 1267956 ABDUL SAKIL MOLLA ABDUL SAKIL MOLLA VILL-BENAI P.O-BENAI (Electrical) 10 Junior Engineer 663 1569394 ABHAY KUMAR RAMESHWAR NATH B/68 SECTOR A DUDHICHUA P O JAYANT (Electrical) PANDEY PANDEY SINGRAULI 486890 11 Junior Engineer 663 1683609 Abhijeet Singh S/O: Laxman Singh NULL NULL Village Bhangiana NULL Garnota (Electrical) Thakur (293) Chamba 12 Junior Engineer 663 1433622 Abhijit kumar Kumar jyotirmay Vill-panki,po+ps-silao, dist-nalanda,state- (Electrical) bihar, pin code-803117 13 Junior Engineer 663 1267623 -

State-Building and the Management of Diversity in India (Thirteenth to Seventeenth Centuries) Corinne Lefèvre

State-building and the Management of Diversity in India (Thirteenth to Seventeenth Centuries) Corinne Lefèvre To cite this version: Corinne Lefèvre. State-building and the Management of Diversity in India (Thirteenth to Sev- enteenth Centuries). Medieval History Journal, SAGE Publications, 2014, 16 (2), pp.425-447. 10.1177/0971945813514907. halshs-01955988 HAL Id: halshs-01955988 https://halshs.archives-ouvertes.fr/halshs-01955988 Submitted on 7 Jan 2020 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. The Medieval History Journal http://mhj.sagepub.com/ State-building and the Management of Diversity in India (Thirteenth to Seventeenth Centuries) Corinne Lefèvre The Medieval History Journal 2013 16: 425 DOI: 10.1177/0971945813514907 The online version of this article can be found at: http://mhj.sagepub.com/content/16/2/425 Published by: http://www.sagepublications.com Additional services and information for The Medieval History Journal can be found at: Email Alerts: http://mhj.sagepub.com/cgi/alerts Subscriptions: http://mhj.sagepub.com/subscriptions -

The Core and the Periphery: a Contribution to the Debate on the Eighteenth Century Author(S): Z

Social Scientist The Core and the Periphery: A Contribution to the Debate on the Eighteenth Century Author(s): Z. U. Malik Source: Social Scientist, Vol. 18, No. 11/12 (Nov. - Dec., 1990), pp. 3-35 Published by: Social Scientist Stable URL: https://www.jstor.org/stable/3517149 Accessed: 03-04-2020 15:29 UTC JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at https://about.jstor.org/terms Social Scientist is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Social Scientist This content downloaded from 117.240.50.232 on Fri, 03 Apr 2020 15:29:21 UTC All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms Z.U. MALIK* The Core and the Periphery: A Contribution to the Debate on the Eighteenth Century** There is a general unanimity among modern historians on seeing the dissolution of Mughal empire as a notable phenomenon cf the eighteenth century. The discord of views relates to the classification and explanation of historical processes behind it, and also to the interpretation and articulation of its impact on political and socio- economic conditions of the country. Most historians sought to explain the imperial crisis from the angle of medieval society in general, relating it to the character and quality of people, and the roles of the diverse classes. -

Copyright by Mohammad Raisur Rahman 2008

Copyright by Mohammad Raisur Rahman 2008 The Dissertation Committee for Mohammad Raisur Rahman certifies that this is the approved version of the following dissertation: Islam, Modernity, and Educated Muslims: A History of Qasbahs in Colonial India Committee: _____________________________________ Gail Minault, Supervisor _____________________________________ Cynthia M. Talbot _____________________________________ Denise A. Spellberg _____________________________________ Michael H. Fisher _____________________________________ Syed Akbar Hyder Islam, Modernity, and Educated Muslims: A History of Qasbahs in Colonial India by Mohammad Raisur Rahman, B.A. Honors; M.A.; M.Phil. Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of The University of Texas at Austin in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of Texas at Austin August 2008 Dedication This dissertation is dedicated to the fond memories of my parents, Najma Bano and Azizur Rahman, and to Kulsum Acknowledgements Many people have assisted me in the completion of this project. This work could not have taken its current shape in the absence of their contributions. I thank them all. First and foremost, I owe my greatest debt of gratitude to my advisor Gail Minault for her guidance and assistance. I am grateful for her useful comments, sharp criticisms, and invaluable suggestions on the earlier drafts, and for her constant encouragement, support, and generous time throughout my doctoral work. I must add that it was her path breaking scholarship in South Asian Islam that inspired me to come to Austin, Texas all the way from New Delhi, India. While it brought me an opportunity to work under her supervision, I benefited myself further at the prospect of working with some of the finest scholars and excellent human beings I have ever known. -

Download Book

"We do not to aspire be historians, we simply profess to our readers lay before some curious reminiscences illustrating the manners and customs of the people (both Britons and Indians) during the rule of the East India Company." @h£ iooi #ld Jap €f Being Curious Reminiscences During the Rule of the East India Company From 1600 to 1858 Compiled from newspapers and other publications By W. H. CAREY QUINS BOOK COMPANY 62A, Ahiritola Street, Calcutta-5 First Published : 1882 : 1964 New Quins abridged edition Copyright Reserved Edited by AmARENDRA NaTH MOOKERJI 113^tvS4 Price - Rs. 15.00 . 25=^. DISTRIBUTORS DAS GUPTA & CO. PRIVATE LTD. 54-3, College Street, Calcutta-12. Published by Sri A. K. Dey for Quins Book Co., 62A, Ahiritola at Express Street, Calcutta-5 and Printed by Sri J. N. Dey the Printers Private Ltd., 20-A, Gour Laha Street, Calcutta-6. /n Memory of The Departed Jawans PREFACE The contents of the following pages are the result of files of old researches of sexeral years, through newspapers and hundreds of volumes of scarce works on India. Some of the authorities we have acknowledged in the progress of to we have been indebted for in- the work ; others, which to such as formation we shall here enumerate ; apologizing : — we may have unintentionally omitted Selections from the Calcutta Gazettes ; Calcutta Review ; Travels Selec- Orlich's Jacquemont's ; Mackintosh's ; Long's other Calcutta ; tions ; Calcutta Gazettes and papers Kaye's Malleson's Civil Administration ; Wheeler's Early Records ; Recreations; East India United Service Journal; Asiatic Lewis's Researches and Asiatic Journal ; Knight's Calcutta; India. -

Annexure-V State/Circle Wise List of Post Offices Modernised/Upgraded

State/Circle wise list of Post Offices modernised/upgraded for Automatic Teller Machine (ATM) Annexure-V Sl No. State/UT Circle Office Regional Office Divisional Office Name of Operational Post Office ATMs Pin 1 Andhra Pradesh ANDHRA PRADESH VIJAYAWADA PRAKASAM Addanki SO 523201 2 Andhra Pradesh ANDHRA PRADESH KURNOOL KURNOOL Adoni H.O 518301 3 Andhra Pradesh ANDHRA PRADESH VISAKHAPATNAM AMALAPURAM Amalapuram H.O 533201 4 Andhra Pradesh ANDHRA PRADESH KURNOOL ANANTAPUR Anantapur H.O 515001 5 Andhra Pradesh ANDHRA PRADESH Vijayawada Machilipatnam Avanigadda H.O 521121 6 Andhra Pradesh ANDHRA PRADESH VIJAYAWADA TENALI Bapatla H.O 522101 7 Andhra Pradesh ANDHRA PRADESH Vijayawada Bhimavaram Bhimavaram H.O 534201 8 Andhra Pradesh ANDHRA PRADESH VIJAYAWADA VIJAYAWADA Buckinghampet H.O 520002 9 Andhra Pradesh ANDHRA PRADESH KURNOOL TIRUPATI Chandragiri H.O 517101 10 Andhra Pradesh ANDHRA PRADESH Vijayawada Prakasam Chirala H.O 523155 11 Andhra Pradesh ANDHRA PRADESH KURNOOL CHITTOOR Chittoor H.O 517001 12 Andhra Pradesh ANDHRA PRADESH KURNOOL CUDDAPAH Cuddapah H.O 516001 13 Andhra Pradesh ANDHRA PRADESH VISAKHAPATNAM VISAKHAPATNAM Dabagardens S.O 530020 14 Andhra Pradesh ANDHRA PRADESH KURNOOL HINDUPUR Dharmavaram H.O 515671 15 Andhra Pradesh ANDHRA PRADESH VIJAYAWADA ELURU Eluru H.O 534001 16 Andhra Pradesh ANDHRA PRADESH Vijayawada Gudivada Gudivada H.O 521301 17 Andhra Pradesh ANDHRA PRADESH Vijayawada Gudur Gudur H.O 524101 18 Andhra Pradesh ANDHRA PRADESH KURNOOL ANANTAPUR Guntakal H.O 515801 19 Andhra Pradesh ANDHRA PRADESH VIJAYAWADA -

Ahmad Riza Khan Barelwi Prelims.044 10/12/2004 4:09 PM Page Ii

prelims.044 10/12/2004 4:09 PM Page i MAKERS of the MUSLIM WORLD Ahmad Riza Khan Barelwi prelims.044 10/12/2004 4:09 PM Page ii SELECTION OF TITLES IN THE MAKERS OF THE MUSLIM WORLD SERIES Series editor: Patricia Crone, Institute for Advanced Study,Princeton ‘Abd al-Malik, Chase F.Robinson Abd al-Rahman III, Maribel Fierro Abu Nuwas, Philip Kennedy Ahmad ibn Hanbal, Christopher Melchert Ahmad Riza Khan Barelwi, Usha Sanyal Al-Ma’mun, Michael Cooperson Al-Mutanabbi, Margaret Larkin Amir Khusraw, Sunil Sharma El Hajj Beshir Agha, Jane Hathaway Fazlallah Astarabadi and the Hurufis, Shazad Bashir Ibn ‘Arabi,William C. Chittick Ibn Fudi,Ahmad Dallal Ikhwan al-Safa, Godefroid de Callatay Shaykh Mufid,Tamima Bayhom-Daou For current information and details of other books in the series, please visit www.oneworld-publications.com/ subjects/makers-of-muslim-world.htm prelims.044 10/12/2004 4:09 PM Page iii MAKERS of the MUSLIM WORLD Ahmad Riza Khan Barelwi In the Path of the Prophet USHA SANYAL prelims.044 10/12/2004 4:09 PM Page iv AHMAD RIZA KHAN BARELWI Oneworld Publications (Sales and Editorial) 185 Banbury Road Oxford OX2 7AR England www.oneworld-publications.com © Usha Sanyal 2005 All rights reserved Copyright under Berne Convention A CIP record for this title is available from the British Library ISBN 1–85168–359–3 Typeset by Jayvee, India Cover and text designed by Design Deluxe Printed and bound in India by Thomson Press Ltd NL08 prelims.044 10/12/2004 4:09 PM Page v TO WILLIAM R. -

The Black Hole of Empire

Th e Black Hole of Empire Th e Black Hole of Empire History of a Global Practice of Power Partha Chatterjee Princeton University Press Princeton and Oxford Copyright © 2012 by Princeton University Press Requests for permission to reproduce material from this work should be sent to Permissions, Princeton University Press Published by Princeton University Press, 41 William Street, Princeton, New Jersey 08540 In the United Kingdom: Princeton University Press, 6 Oxford Street, Woodstock, Oxfordshire OX20 1TW press.princeton.edu All Rights Reserved Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Chatterjee, Partha, 1947- Th e black hole of empire : history of a global practice of power / Partha Chatterjee. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-0-691-15200-4 (hardcover : alk. paper)— ISBN 978-0-691-15201-1 (pbk. : alk. paper) 1. Bengal (India)—Colonization—History—18th century. 2. Black Hole Incident, Calcutta, India, 1756. 3. East India Company—History—18th century. 4. Imperialism—History. 5. Europe—Colonies—History. I. Title. DS465.C53 2011 954'.14029—dc23 2011028355 British Library Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available Th is book has been composed in Adobe Caslon Pro Printed on acid-free paper. ∞ Printed in the United States of America 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 To the amazing surgeons and physicians who have kept me alive and working This page intentionally left blank Contents List of Illustrations ix Preface xi Chapter One Outrage in Calcutta 1 Th e Travels of a Monument—Old Fort William—A New Nawab—Th e Fall