DON QUIJOTE (By Miguel De Cervantes Saavedra, Part I in 1605; Part II in 1613)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Don Quixote and Legacy of a Caricaturist/Artistic Discourse

Don Quixote and the Legacy of a Caricaturist I Artistic Discourse Rupendra Guha Majumdar University of Delhi In Miguel de Cervantes' last book, The Tria/s Of Persiles and Sigismunda, a Byzantine romance published posthumously a year after his death in 1616 but declared as being dedicated to the Count of Lemos in the second part of Don Quixote, a basic aesthetie principIe conjoining literature and art was underscored: "Fiction, poetry and painting, in their fundamental conceptions, are in such accord, are so close to each other, that to write a tale is to create pietoríal work, and to paint a pieture is likewise to create poetic work." 1 In focusing on a primal harmony within man's complex potential of literary and artistic expression in tandem, Cervantes was projecting a philosophy that relied less on esoteric, classical ideas of excellence and truth, and more on down-to-earth, unpredictable, starkly naturalistic and incongruous elements of life. "But fiction does not", he said, "maintain an even pace, painting does not confine itself to sublime subjects, nor does poetry devote itself to none but epie themes; for the baseness of lífe has its part in fiction, grass and weeds come into pietures, and poetry sometimes concems itself with humble things.,,2 1 Quoted in Hans Rosenkranz, El Greco and Cervantes (London: Peter Davies, 1932), p.179 2 Ibid.pp.179-180 Run'endra Guha It is, perhaps, not difficult to read in these lines Cervantes' intuitive vindication of the essence of Don Quixote and of it's potential to generate a plural discourse of literature and art in the years to come, at multiple levels of authenticity. -

2022 Spain: Spanish in the Land of Don Quixote

Please see the NOTICE ON PROGRAM UPDATES at the bottom of this sample itinerary for details on program changes. Please note that program activities may change in order to adhere to COVID-19 regulations. SPAIN: Spanish in the Land of Don Quixote™ For more than a language course, travel to Toledo, Madrid & Salamanca - the perfect setting for a full Spanish experience in Castilla-La Mancha. OVERVIEW HIGHLIGHTS On this program you will travel to three cities in the heart of Spain, all ★ with rich histories that bring a unique taste of the country with each stop. Improve your Spanish through Start your journey in Madrid, the Spanish capital. Then head to Toledo, language immersion ★ where your Spanish immersion will truly begin and will make up the Walk the historic streets of Toledo, heart of your program experience. Journey west to Salamanca, where known as "the city of three you'll find the third oldest European university and Cervantes' alma cultures" ★ mater. Finally, if you opt to stay for our Homestay Extension, you will live Visit some of Madrid's oldest in Toledo for a week with a local family and explore Almagro, home to restaurants on a tapas tours ★ one of the oldest open air theaters in the world. Go kayaking on the Alto Tajo River ★ Help to run a summer English language camp for Spanish 14-DAY PROGRAM Tuition: $4,399 children Service Hours: 20 ★ Stay an extra week and live with a June 25 – July 8, 2022 Language Hours: 35 Spanish family to perfect your + 7-NIGHT HOMESTAY (OPTIONAL) Max Group Size: 32 Spanish language skills (Homestay July 8 - July 15 Age Range: 14-19 Add 10 service hours add-on only) Add 20 language hours Student-to-Staff Ratio: 8-to-1 Add $1,699 tuition Airport: MAD experienceGLA.com | +1 858-771-0645 | @GLAteens DAILY BREAKDOWN Actual schedule of activities will vary by program session. -

Don Quijote Von Miguel De Cer Vantes Seit Nunmehr Vier Jahrhunderten Generationen Von Lesern Immer Wieder Neu in Seinen Bann

DON_Schutzumschlag_Grafik_rechts.FH11 Wed May 30 13:04:18 2007 Seite 1 C M Y CM MY CY CMY K Wie kein zweiter Roman zieht der Don Quijote von Miguel de Cer vantes seit nunmehr vier Jahrhunderten Generationen von Lesern immer wieder neu in seinen Bann. Abgefasst im Spanien des frühen 17. Jahrhunderts, das zu jener Zeit die Geschicke Europas wesentlich mitbestimmte, wurde der Roman bald zum Inbegriff der spanischen Literatur und Kultur. Von Madrid aus hat er auf den Rest Europas ausgestrahlt und Denker, Dichter, Künstler, Komponisten und später Tilmann Altenberg auch Filmemacher zur Auseinandersetzung mit ihm angeregt. Klaus Meyer-Minnemann (Hg.) Die acht Beiträge des Bandes erkunden zentrale Aspekte des cervantinischen Romans und gehen seiner Rezeption und Verar- beitung in Literatur, Kunst, Film und Musik im europäischen Kontext nach. Europäische Dimensionen des Inhalt: · Klaus Meyer-Minnemann: Zur Entstehung, Konzeption und Wir- Film und Musik Kunst, in Literatur, Don Quijote in Literatur, Kunst, kung des Don Quijote in der europäischen Literatur · Hans-Jörg Neuschäfer: Boccaccio, Cervantes und der utopische Possibilismus Film und Musik · Katharina Niemeyer: Der Furz des Sancho Panza oder Don Quijote als komischer Roman Don Quijote · Dieter Ingenschay: Don Quijote in der spanischen und deutschen Literaturwissenschaft · Johannes Hartau: Don Quijote als Thema der bildenden Kunst · Tilmann Altenberg: Don Quijote im Film · Bárbara P. Esquival-Heinemann: Don Quijote in der deutschsprachi- gen Oper · Begoña Lolo: Musikalische Räume des Don -

Iconografía Militar Del Quijote: Emblemas De Aviación1

Revista de la CECEL, 15 2015, pp. 189-206 ISSN: 1578-570-X ICONOGRAFÍA MILITAR DEL QUIJOTE: EMBLEMAS DE AVIACIÓN1 JOSÉ MANUEL PAÑEDA RUIZ UNED RESUMEN ABSTRACT La popular obra de Cervantes ha sido ob- The popular text of Cervantes has received a jeto de una pluralidad de fi guraciones que plurality of confi gurations that have illustrat- han ilustrado la obra; mientras que por otro ed the work; while on the other hand an ex- lado surge en torno a dicho texto una extensa tensive popular iconography arises over the iconografía popular. Sin embargo, las repre- text. However, the representations in the mili- sentaciones en el ámbito militar son escasas, tary fi eld are scarce, being mainly focused in estando centradas principalmente en la esfera the fi eld of aviation. In this study a tour of the de la aviación. En este estudio se realiza un latter has been made, in order to analyze their recorrido por estas últimas, con el fi n de ana- origin, meaning and its relationship with the lizar su procedencia, signifi cado y su relación Quixote. con el Quijote.. PALABRAS CLAVE KEY WORDS Quijote, aviación, iconografía popular, pilo- Quixote, aviation, popular iconography, tos de caza. fi ghter pilots. 1. INTRODUCCIÓN La celebración del III centenario de la publicación de la segunda parte del Quijote2 en 1915 coincidió con otros dos acontecimientos que aunque inicial- mente no guarden relación aparente con la obra cervantina, posteriormente se verá que están intimamente ligados con la línea de trabajo del presente texto. El primero de ellos fue la Guerra Europea o Gran Guerra, o en palabras de Woodrow Wilson, presidente de Estados Unidos: 1 Fecha de recepción: 3 de diciembre de 2015. -

Review of R. M. Flores, Sancho Panza Through Three Hundred Seventy

Bulletin of Hispanic Studies, 61 (1984), 507–08. [email protected] http://bigfoot.com/~daniel.eisenberg R. M. Flores, Sancho Panza through Three Hundred Seventy-five Years of Continuations, Imitations, and Criticism, 1605–1980. Newark, Delaware: Juan de la Cuesta, 1982. x + 233 pp. This is a study of the fortunes of Sancho Panza subsequent to Cervantes, followed by a chapter analyzing ‘Cervantes’ Sancho’. It is a bitter history of what the author views as misinterpretation, a study of ‘disarray, irrelevance, and repetition’, which constitute the overall picture of the topic (149). Included are three bibliogra- phies, one of which is a chronological listing without references, 54 pages of appendices with categorized information about Sancho found in Don Quixote, a tabulation of the length of Sancho’s speeches, and an index of proper names. Flores’ focus in his historical survey is to see if and by whom Sancho has been presented accurately. This is a fair question when dealing with scholarship, but he evaluates creative literature from the same perspective. Thus, a novel of José Larraz López ‘fails to throw any useful light on Sancho’s character’ (105), and we are told that ‘it is impossible to accept [a novel of Jean Camp] as a genuine continuation of Cervantes’ novel’ (105). Flores praises Tolkien because ‘in most…respects the characters of Tolkien and Cervantes are alike’ (108). The question of why a novelist, dramatist, or poet should be expected to be faithful to Cervantes is never addressed, nor is the validity of authorial interpretation and intent explored. Even aside from this, the treatment of creative literature is incomplete, and relies heavily on secondary sources: thus, the discussion of seventeenth-century Spanish images of Sancho is based exclusively on the summary notes in Miguel He- rrero García’s Estimaciones literarias del siglo XVIII. -

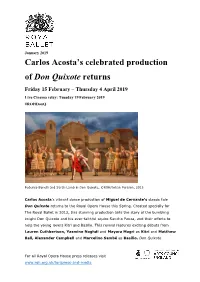

Don Quixote Press Release 2019

January 2019 Carlos Acosta’s celebrated production of Don Quixote returns Friday 15 February – Thursday 4 April 2019 Live Cinema relay: Tuesday 19 February 2019 #ROHDonQ Federico Bonelli and Sarah Lamb in Don Quixote, ©ROH/Johan Persson, 2013 Carlos Acosta’s vibrant dance production of Miguel de Cervante’s classic tale Don Quixote returns to the Royal Opera House this Spring. Created specially for The Royal Ballet in 2013, this stunning production tells the story of the bumbling knight Don Quixote and his ever-faithful squire Sancho Panza, and their efforts to help the young lovers Kitri and Basilio. This revival features exciting debuts from Lauren Cuthbertson, Yasmine Naghdi and Mayara Magri as Kitri and Matthew Ball, Alexander Campbell and Marcelino Sambé as Basilio. Don Quixote For all Royal Opera House press releases visit www.roh.org.uk/for/press-and-media includes a number of spectacular solos and pas de deux as well as outlandish comedy and romance as the dashing Basilio steals the heart of the beautiful Kitri. Don Quixote will be live streamed to cinemas on Tuesday 19 February as part of the ROH Live Cinema Season. Carlos Acosta previously danced the role of Basilio in many productions of Don Quixote. He was invited by Kevin O’Hare Director of The Royal Ballet, to re-stage this much-loved classic in 2013. Acosta’s vibrant production evokes sunny Spain with designs by Tim Hatley who has also created productions for the National Theatre and for musicals including Dreamgirls, The Bodyguard and Shrek. Acosta’s choreography draws on Marius Petipa’s 1869 production of this classic ballet and is set to an exuberant score by Ludwig Minkus arranged and orchestrated by Martin Yates. -

Is There a Hidden Jewish Meaning in Don Quixote?

From: Cervantes: Bulletin of the Cervantes Society of America , 24.1 (2004): 173-88. Copyright © 2004, The Cervantes Society of America. Is There a Hidden Jewish Meaning in Don Quixote? MICHAEL MCGAHA t will probably never be possible to prove that Cervantes was a cristiano nuevo, but the circumstantial evidence seems compelling. The Instrucción written by Fernán Díaz de Toledo in the mid-fifteenth century lists the Cervantes family as among the many noble clans in Spain that were of converso origin (Roth 95). The involvement of Miguel’s an- cestors in the cloth business, and his own father Rodrigo’s profes- sion of barber-surgeon—both businesses that in Spain were al- most exclusively in the hand of Jews and conversos—are highly suggestive; his grandfather’s itinerant career as licenciado is so as well (Eisenberg and Sliwa). As Américo Castro often pointed out, if Cervantes were not a cristiano nuevo, it is hard to explain the marginalization he suffered throughout his life (34). He was not rewarded for his courageous service to the Spanish crown as a soldier or for his exemplary behavior during his captivity in Al- giers. Two applications for jobs in the New World—in 1582 and in 1590—were denied. Even his patron the Count of Lemos turn- 173 174 MICHAEL MCGAHA Cervantes ed down his request for a secretarial appointment in the Viceroy- alty of Naples.1 For me, however, the most convincing evidence of Cervantes’ converso background is the attitudes he displays in his work. I find it unbelievable that anyone other than a cristiano nuevo could have written the “Entremés del retablo de las maravi- llas,” for example. -

Cervantes and the Spanish Baroque Aesthetics in the Novels of Graham Greene

TESIS DOCTORAL Título Cervantes and the spanish baroque aesthetics in the novels of Graham Greene Autor/es Ismael Ibáñez Rosales Director/es Carlos Villar Flor Facultad Facultad de Letras y de la Educación Titulación Departamento Filologías Modernas Curso Académico Cervantes and the spanish baroque aesthetics in the novels of Graham Greene, tesis doctoral de Ismael Ibáñez Rosales, dirigida por Carlos Villar Flor (publicada por la Universidad de La Rioja), se difunde bajo una Licencia Creative Commons Reconocimiento-NoComercial-SinObraDerivada 3.0 Unported. Permisos que vayan más allá de lo cubierto por esta licencia pueden solicitarse a los titulares del copyright. © El autor © Universidad de La Rioja, Servicio de Publicaciones, 2016 publicaciones.unirioja.es E-mail: [email protected] CERVANTES AND THE SPANISH BAROQUE AESTHETICS IN THE NOVELS OF GRAHAM GREENE By Ismael Ibáñez Rosales Supervised by Carlos Villar Flor Ph.D A thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy At University of La Rioja, Spain. 2015 Ibáñez-Rosales 2 Ibáñez-Rosales CONTENTS Abbreviations ………………………………………………………………………….......5 INTRODUCTION ...…………………………………………………………...….7 METHODOLOGY AND STRUCTURE………………………………….……..12 STATE OF THE ART ..……….………………………………………………...31 PART I: SPAIN, CATHOLICISM AND THE ORIGIN OF THE MODERN (CATHOLIC) NOVEL………………………………………38 I.1 A CATHOLIC NOVEL?......................................................................39 I.2 ENGLISH CATHOLICISM………………………………………….58 I.3 THE ORIGIN OF THE MODERN -

Established in Alfaro, La Rioja, Castile, Kingdom of Spain, Since XIV Century

Hidalgo de Castilla y León Compañía de Ballesteros de la Villa de Alfaro (La Rioja) Established in Alfaro, La Rioja, Castile, Kingdom of Spain, since XIV century Royal Protector and Honorary Chief: HM The King Juan Carlos I. of Spain Chief: SAR The Prince Alvaro de Bourbon Duque de Galliera Commander: Alfonso de Ceballos-Escalera y Gila, Duke of Ostuni in the Kingdom of the Two Sicilies, Marquess of La Floresta and Lord of the Castle of Arbeteta in the Kingdom of Spain The Noble Compañia de Ballesteros Hijosdalgo de San Felipe y Santiago, is a little nobiliary-sportive-religious association founded in the XIV century, as detailed enclose. Since XVIII century it was losing its nobiliary and sportive uses, remaining only those religious (like Easter procession). Among the several forms that historically had adopted the Spanish nobiliary colleges -such as corporations, brotherhoods and companies, and chivalry orders- are barely mentioned by its rarely, the military character associations, like the Noble Compañia de Ballesteros Hijosdalgo de San Felipe y Santiago raised in the XIV century in the ancient town of Alfaro (La Rioja, ancient kingdom of Castile, today Kingdom of Spain). The Ballesteros as war and hunting weapon it was already known by Romans-Ballesteros comes from Latin word 'ballo', which means to throw- and by Byzantines, in whose documents frequently appears. After a relative dark period, it came to have a preeminent place during XI century in European weapon system, as well as being a military support -remember its importance in the Hundred Years War- as hunting article. Medieval sources give us what kind of arrows it threw, with a huge of different uses and meanings, even stone bullets capable to get through any armour from a distance longer than 250 feet. -

Guías Diarias Para El Quijote Parte I, Cap

Guías diarias para el Quijote Parte I, cap. 3 RESUMEN: Don Quixote begs the innkeeper, whom he mistakes for the warden of the castle, to make him a knight the next day. Don Quixote says Parte I, cap. 1 that he will watch over his armor until the morning in the chapel, which, RESUMEN: Don Quixote is a fan of “books of chivalry” and spends most he learns, is being restored. A muleteer comes to water his mules and of his time and money on these books. These tales of knight-errantry drive tosses aside the armor and is attacked by Don Quixote. A second muleteer him crazy trying to fathom them and he resolves to resuscitate this does the same thing with the same result. Made nervous by all this, the forgotten ancient order in his modern day in order to help the needy. He innkeeper makes Don Quixote a knight before the morning arrives. cleans his ancestor’s armor, names himself Don Quixote, names his horse, and finds a lady to be in love with. PREGUNTAS: 1. ¿Qué le pide don Quijote al ventero? PREGUNTAS: 2. ¿Por qué quiere hacer esto el ventero? 1. ¿De dónde es don Quijote? 3. ¿Qué aventuras ha tenido el ventero? 2. ¿Era rico don Quijote? 4. ¿Por qué busca don Quijote la capilla? 3. ¿Quiénes vivían con don Quijote? 5. ¿Qué consejos prácticos le da el ventero a don Quijote? 4. ¿Por qué quería tomar la pluma don Quijote? 6. ¿Qué quería hacer el primer arriero al acercarse a don Quijote por la 5. -

Language and Gender in Don Quixote: Teresa Panza As Subject

Language and Gender in Don Quixote: Teresa Panza as Subject Patricia A. Heid University of California, Berkeley Teresa Panza, the wife of Don Quijote’s famous squire Sancho, is depicted in a drawing in Concha Espina’s book, Mujeres del Quijote, as an older and somewhat heavy woman, dressed in the style of the pueblo, with a sensitive facial expression and an overall domestic air. This is, in fact, the way in which we imagine her through most of Part I, when her identity is limited to that of a main character’s wife, and a somewhat unintelligent one at that. Concha Espina herself says that Cervantes’ book offers her to us as “la digna compaflera del buen Sancho, llena de rustiquez y de ignorancia” (90). Other critics have at least recognized that Teresa, like most of Cervantes ’ female characters, exhibits alertness and resolve (Combet 67). Teresa, however, eludes these simple characterizations. Dressed in all the trappings of an ignorant and obedient wife, she bounds over the linguistic and social borders which her gender imposes. In the open space beyond, Teresa develops discourse as a non-gendered subject. Her voice becomes one which her husband must reckon with in the power struggle which forms the context of their language. By analyzing the strategies for control utilized in this conflict, we see that it is similar to another power struggle with which we are quite familiar: that of Don Quijote and Sancho. The parallels discovered between the two highlight important aspects of the way in which Teresa manages her relationship to power, 1 and reveal that both conflicts are fundamentally the same. -

Exhibition Booklet, Printing Cervantes

This man you see here, with aquiline face, chestnut hair, smooth, unwrinkled brow, joyful eyes and curved though well-proportioned nose; silvery beard which not twenty years ago was golden, large moustache, small mouth, teeth neither small nor large, since he has only six, and those are in poor condition and worse alignment; of middling height, neither tall nor short, fresh-faced, rather fair than dark; somewhat stooping and none too light on his feet; this, I say, is the likeness of the author of La Galatea and Don Quijote de la Mancha, and of him who wrote the Viaje del Parnaso, after the one by Cesare Caporali di Perusa, and other stray works that may have wandered off without their owner’s name. This man you see here, with aquiline face, chestnut hair, smooth, unwrinkled brow, joyful eyes and curved though well-proportioned nose; silvery beard which not twenty years ago was golden, large moustache, small mouth, teeth neither small nor large, since he has only six, and those are in poor condition and worse alignment; of middling height, neither tall nor short, fresh-faced, rather fair than dark; somewhat stooping and none too light on his feet; this, I say, is the likeness of the author of La Galatea and Don Quijote de la Mancha, and of him who wrote the Viaje del Parnaso, after the one by Cesare Caporali di Perusa, and other stray works that may have wandered off without their owner’s name. This man you see here, with aquiline Printingface, chestnut hair, smooth,A LegacyCervantes: unwrinkled of Words brow, and Imagesjoyful eyes and curved though well-proportioned nose; Acknowledgements & Sponsors: With special thanks to the following contributors: Drs.