The Figure Sculpture and Iconography of the West Front of Peterborough

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Hereward and the Barony of Bourne File:///C:/Edrive/Medieval Texts/Articles/Geneaology/Hereward.Htm

hereward and the Barony of Bourne file:///C:/EDrive/Medieval Texts/Articles/Geneaology/hereward.htm Lincolnshire History and Archaeology, 29 (1994), 7-10. Hereward 'the Wake' and the Barony of Bourne: a Reassessment of a Fenland Legend [1] Hereward, generally known as 'the Wake', is second only to Robin Hood in the pantheon of English heroes. From at least the early twelfth century his deeds were celebrated in Anglo-Norman aristocratic circles, and he was no doubt the subject of many a popular tale and song from an early period. [2] But throughout the Middle Ages Hereward's fame was local, being confined to the East Midlands and East Anglia. [3] It was only in the nineteenth century that the rebel became a truly national icon with the publication of Charles Kingsley novel Hereward the Wake .[4] The transformation was particularly Victorian: Hereward is portrayed as a prototype John Bull, a champion of the English nation. The assessment of historians has generally been more sober. Racial overtones have persisted in many accounts, but it has been tacitly accepted that Hereward expressed the fears and frustrations of a landed community under threat. Paradoxically, however, in the light of the nature of that community, the high social standing that the tradition has accorded him has been denied. [5] The earliest recorded notice of Hereward is the almost contemporary annal for 1071 in the D version of the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle. A Northern recension probably produced at York,[6] its account of the events in the fenland are terse. It records the plunder of Peterborough in 1070 'by the men that Bishop Æthelric [late of Durham] had excommunicated because they had taken there all that he had', and the rebellion of Earls Edwin and Morcar in the following year. -

Hheritage Gazette of the Trent Valley, Vol. 20, No. 2 August 2015Eritage

ISSN 1206-4394 herITage gazeTTe of The TreNT Valley Volume 21, Number 2, august 2016 Table of Contents President’s Corner ………………….……………………………………..………………...…… Rick Meridew 2 Italian Immigration to Peterborough: the overview ……………………………………………. Elwood H. Jones 3 Appendix: A Immigration trends to North America, 4; B Immigration Statistics to USA, 5; C Immigration statistics from 1921 printed census, 6; D Using the personal census 1921, 6; E Using Street Directories 1925, 7 Italian-Canadians of Peterborough, Ontario: First wave 1880-1925 ……………………..………. Berenice Pepe 9 What’s in a Name: Stony or Stoney? …………………………………………………………. Elwood H. Jones 14 Queries …………………………………………………………..…………… Heather Aiton Landry and others 17 George Stenton and the Fenian Raid ………………………………………………….……… Stephen H. Smith 19 Building Boom of 1883 ……………………………………………………………………….. Elwood H. Jones 24 Postcards from Peterborough and the Kawarthas …………………………… …………………………………… 26 Discovering Harper Park: a walkabout in Peterborough’s urban green space ……………………… Dirk Verhulst 27 Pathway of Fame ………………………………………………………………………………………………….. 28 Hazelbrae Barnardo Home Memorial 1921, 1922, and 1923 [final instalment] ……… John Sayers and Ivy Sucee 29 Thomas Ward fonds #584 …………………………………………..……………………. TVA Archives Report 33 J. J. Duffus, Car King, Mayor and Senator ………………………………………………………………………… 34 Senator Joseph Duffus Dies in City Hospital ………………………….…… Examiner, 7 February 1957 34 A plaque in honour of J. J. Duffus will be unveiled this fall …………………………………………….. 37 Special issue on Quaker Oats 115 Years in Peterborough: invitation for ideas ……………………………… Editor 37 Trent Valley Archives Honoured with Civic Award ………………………………………………………………… 42 Ladies of the Lake Cemetery Tour ………………………………………………………..………………………… 43 The Log of the “Dorothy” …………………………………………………….…………………….. F. H. Dobbin 39 Frank Montgomery Fonds #196 ………………………………………………….………… TVA Archives Report 40 District of Colborne founding document: original at Trent Valley Archives ……………………………………….. 41 Genealogical Resources at Trent Valley Archives ………………………………..……………. -

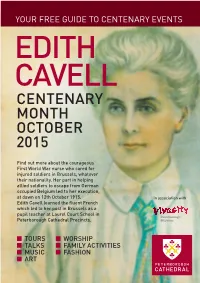

Edith Cavell Centenary Month October 2015

YOUR FREE GUIDE TO CENTENARY EVENTS EDITH CAVELL CENTENARY MONTH OCTOBER 2015 Find out more about the courageous First World War nurse who cared for injured soldiers in Brussels, whatever their nationality. Her part in helping allied soldiers to escape from German occupied Belgium led to her execution, at dawn on 12th October 1915. In association with Edith Cavell learned the fluent French which led to her post in Brussels as a pupil teacher at Laurel Court School in Peterborough Peterborough Cathedral Precincts. MusPeeumterborough Museum n TOURS n WORSHIP n TALKS n FAMILY ACTIVITIES n MUSIC n FASHION n ART SATURDAY 10TH OCTOBER FRIDAY 9TH OCTOBER & SUNDAY 11TH OCTOBER Edith Cavell Cavell, Carbolic and A talk by Diana Chloroform Souhami At Peterborough Museum, 7.30pm at Peterborough Priestgate, PE1 1LF Cathedral Tours half hourly, Diana Souhami’s 10.00am – 4.00pm (lasts around 50 minutes) biography of Edith This theatrical tour with costumed re-enactors Cavell was described vividly shows how wounded men were treated by The Sunday Times during the Great War. With the service book for as “meticulously a named soldier in hand you will be sent to “the researched and trenches” before being “wounded” and taken to sympathetic”. She the casualty clearing station, the field hospital, will re-tell the story of Edith Cavell’s life: her then back to England for an operation. In the childhood in a Norfolk rectory, her career in recovery area you will learn the fate of your nursing and her role in the Belgian resistance serviceman. You will also meet “Edith Cavell” and movement which led to her execution. -

Castor Village – Overview 1066 to 2000

Chapter 5 Castor Village – Overview 1066 to 2000 Introduction One of the earliest recorded descriptions of Castor as a village is by a travelling historian, William Camden who, in 1612, wrote: ‘The Avon or Nen river, running under a beautiful bridge at Walmesford (Wansford), passes by Durobrivae, a very ancient city, called in Saxon Dormancaster, took up a great deal of ground on each side of the river in both counties. For the little village of Castor which stands one mile from the river, seems to have been part of it, by the inlaid chequered pavements found there. And doubtless it was a place of more than ordinary note; in the adjoining fields (which instead of Dormanton they call Normangate) such quantities of Roman coins are thrown up you would think they had been sewn. Ermine Street, known as the forty foot way or The Way of St Kyneburgha, now known as Lady Connyburrow’s Way must have been up towards Water Newton, if one may judge from, it seems to have been paved with a sort of cubical bricks and tiles.’ [1] By Camden’s time, Castor was a village made up of a collection of tenant farms and cottages, remaining much the same until the time of the Second World War. The village had developed out of the late Saxon village of the time of the Domesday Book, that village having itself grown up among the ruins of the extensive Roman villa and estate that preceded it. The pre-conquest (1066) settlement of Castor is described in earlier chapters. -

A HISTORY of OUR CHURCH Welcome To

A HISTORY OF OUR CHURCH Welcome to our beautiful little church, named after St Botolph*, the 7th century patron saint of wayfarers who founded many churches in the East of England. The present church on this site was built in 1263 in the Early English style. This was at the request and expense of Sir William de Thorpe, whose family later built Longthorpe Tower. At first a chapel in the parish of St John it was consecrated as a church in 1850. The church has been well used and much loved for over 750 years. It is noted for its stone, brass and stained glass memorials to men killed in World War One, to members of the St John and Strong families of Thorpe Hall and to faithful members of the congregation. Below you will find: A.) A walk round tour with a plan and descriptions of items in the nave and chancel (* means there is more about this person or place in the second half of this history.) The nave and chancel have been divided into twelve sections corresponding to the numbers on the map. 1) The Children’s Corner 2) The organ area 3) The northwest window area 4) The North Aisle 5) The Horrell Window 6) The Chancel, north side 7) The Sanctuary Area 8) The Altar Rail 9) The Chancel, south side 10) The Gaskell brass plaques 11) Memorials to the Thorpe Hall families 12) The memorial book and board; the font B) The history of St Botolph, this church and families connected to it 1) St Botolph 2) The de Thorpe Family, the church and Longthorpe Tower 3) History of the church 4) The Thorpe Hall connection: the St Johns and Strongs 5) Father O-Reilly; the Oxford Movement A WALK ROUND THE CHURCH This guide takes you round the church in a clockwise direction. -

PDFHS CD/Download Overview 100 Local War Memorials the CD Has Photographs of Almost 90% of the Memorials Plus Information on Their Current Location

PDFHS CD/Download Overview 100 Local War Memorials The CD has photographs of almost 90% of the memorials plus information on their current location. The Memorials - listed in their pre-1970 counties: Cambridgeshire: Benwick; Coates; Stanground –Church & Lampass Lodge of Oddfellows; Thorney, Turves; Whittlesey; 1st/2nd Battalions. Cambridgeshire Regiment Huntingdonshire: Elton; Farcet; Fletton-Church, Ex-Servicemen Club, Phorpres Club, (New F) Baptist Chapel, (Old F) United Methodist Chapel; Gt Stukeley; Huntingdon-All Saints & County Police Force, Kings Ripton, Lt Stukeley, Orton Longueville, Orton Waterville, Stilton, Upwood with Gt Ravely, Waternewton, Woodston, Yaxley Lincolnshire: Barholm; Baston; Braceborough; Crowland (x2); Deeping St James; Greatford; Langtoft; Market Deeping; Tallington; Uffington; West Deeping: Wilsthorpe; Northamptonshire: Barnwell; Collyweston; Easton on the Hill; Fotheringhay; Lutton; Tansor; Yarwell City of Peterborough: Albert Place Boys School; All Saints; Baker Perkins, Broadway Cemetery; Boer War; Book of Remembrance; Boy Scouts; Central Park (Our Jimmy); Co-op; Deacon School; Eastfield Cemetery; General Post Office; Hand & Heart Public House; Jedburghs; King’s School: Longthorpe; Memorial Hospital (Roll of Honour); Museum; Newark; Park Rd Chapel; Paston; St Barnabas; St John the Baptist (Church & Boys School); St Mark’s; St Mary’s; St Paul’s; St Peter’s College; Salvation Army; Special Constabulary; Wentworth St Chapel; Werrington; Westgate Chapel Soke of Peterborough: Bainton with Ashton; Barnack; Castor; Etton; Eye; Glinton; Helpston; Marholm; Maxey with Deeping Gate; Newborough with Borough Fen; Northborough; Peakirk; Thornhaugh; Ufford; Wittering. Pearl Assurance National Memorial (relocated from London to Lynch Wood, Peterborough) Broadway Cemetery, Peterborough (£10) This CD contains a record and index of all the readable gravestones in the Broadway Cemetery, Peterborough. -

The Heritage Gazette of the Trent Valley Volume 14, Number 2, August 2009

ISSN 1206-4394 The Heritage Gazette of the Trent Valley Volume 14, number 2, August 2009 Table of Contents West End Walk Planned ……………………………………………..………. Kelly McGillis 2 Adventures of John Keleher: An Irishman, A Sailor, an Immigrant ……….…. Don Willcock 3 Peterborough Miscellaneous Directory 1906 ……………….……… Peterborough Directory 7 Rambles on Chambers Street ……………………...…………………………. Andrew Elliott 15 A Short History of Lakefield College School ………………………….………….. Kim Krenz 17 Peterborough’s Canadian Icons …… ………. Gordon Young, Lakefield Heritage Research 20 Diary of A. J. Grant, 1912 ………………………………………….. Dennis Carter-Edwards 21 Queries ………………………………………………………………………… Diane Robnik 23 The Surname Barry: Irish-Cork Origins and History ……………………………. David Barry 25 Book notes: …………………………………………………………………………………….. 31 Paterson, School Days, Cool Days; Galvin, Days of My Years; Cahorn, The Incredible Walk. Peterman, Sisters in Two Worlds East Peterborough, Douro Township, 1901 Census, April 1901, Section 1 ……………….. 32 First Nations of the Trent Valley 1831 ……. …………………………………. Thomas Carr 40 The Ecological Economy …………………………………………………….……. David Bell 42 News, Views and Reviews ………………………………………………………………………. 43 Trent Valley Archives upcoming events; Wall of Honour update; Notice of new book, Elwood Jones, Historian’s Notebook Cover picture: Peterborough waterfront, late 1930s. Note Peterborough Canoe Company in foreground. In the distance you can see Peterborough Cereal Company, Quaker Oats and the Hunter Street Bridge. Notice the CPR tracks along the Otonabee -

Northamptonshire Past and Present, No 61

JOURNAL OF THE NORTHAMPTONSHIRE RECORD SOCIETY WOOTTON HALL PARK, NORTHAMPTON NN4 8BQ ORTHAMPTONSHIRE CONTENTS Page NPAST AND PRESENT Notes and News . 5 Number 61 (2008) Fact and/or Folklore? The Case for St Pega of Peakirk Avril Lumley Prior . 7 The Peterborough Chronicles Nicholas Karn and Edmund King . 17 Fermour vs Stokes of Warmington: A Case Before Lady Margaret Beaufort’s Council, c. 1490-1500 Alan Rogers . 30 Daventry’s Craft Companies 1574-1675 Colin Davenport . 42 George London at Castle Ashby Peter McKay . 56 Rushton Hall and its Parklands: A Multi-Layered Landscape Jenny Burt . 64 Politics in Late Victorian and Edwardian Northamptonshire John Adams . 78 The Wakerley Calciner Furnaces Jack Rodney Laundon . 86 Joan Wake and the Northamptonshire Record Society Sir Hereward Wake . 88 The Northamptonshire Reference Database Barry and Liz Taylor . 94 Book Reviews . 95 Obituary Notices . 102 Index . 103 Cover illustration: Courteenhall House built in 1791 by Sir William Wake, 9th Baronet. Samuel Saxon, architect, and Humphry Repton, landscape designer. Number 61 2008 £3.50 NORTHAMPTONSHIRE PAST AND PRESENT PAST NORTHAMPTONSHIRE Northamptonshire Record Society NORTHAMPTONSHIRE PAST AND PRESENT 2008 Number 61 CONTENTS Page Notes and News . 5 Fact and/or Folklore? The Case for St Pega of Peakirk . 7 Avril Lumley Prior The Peterborough Chronicles . 17 Nicholas Karn and Edmund King Fermour vs Stokes of Warmington: A Case Before Lady Margaret Beaufort’s Council, c.1490-1500 . 30 Alan Rogers Daventry’s Craft Companies 1574-1675 . 42 Colin Davenport George London at Castle Ashby . 56 Peter McKay Rushton Hall and its Parklands: A Multi-Layered Landscape . -

The Praetorium of Edmund Artis: a Summary of Excavations and Surveys of the Palatial Roman Structure at Castor, Cambridgeshire 1828–2010 by STEPHEN G

Britannia 42 (2011), 23–112 doi:10.1017/S0068113X11000614 The Praetorium of Edmund Artis: A Summary of Excavations and Surveys of the Palatial Roman Structure at Castor, Cambridgeshire 1828–2010 By STEPHEN G. UPEX With contributions by ADRIAN CHALLANDS, JACKIE HALL, RALPH JACKSON, DAVID PEACOCK and FELICITY C. WILD ABSTRACT Antiquarian and modern excavations at Castor, Cambs., have been taking place since the seventeenth century. The site, which lies under the modern village, has been variously described as a Roman villa, a guild centre and a palace, while Edmund Artis working in the 1820s termed it the ‘Praetorium’. The Roman buildings covered an area of 3.77 ha (9.4 acres) and appear to have had two main phases, the latter of which formed a single unified structure some 130 by 90 m. This article attempts to draw together all of the previous work at the site and provide a comprehensive plan, a set of suggested dates, and options on how the remains could be interpreted. INTRODUCTION his article provides a summary of various excavations and surveys of a large group of Roman buildings found beneath Castor village, Cambs. (centred on TL 124 984). The village of Castor T lies 8 km to the west of Peterborough (FIG. 1) and rises on a slope above the first terrace gravel soils of the River Nene to the south. The underlying geology is mixed, with the lower part of the village (8 m AOD) sitting on both terrace gravel and Lower Lincolnshire limestone, while further up the valley side the Upper Estuarine Series and Blisworth Limestone are encountered, with a capping of Blisworth Clay at the top of the slope (23 m AOD).1 The slope of the ground on which the Roman buildings have been arranged has not been emphasised enough or even mentioned in earlier accounts of the site.2 The current evidence suggests that substantial Roman terracing and the construction of revetment or retaining walls was required to consolidate the underlying geology. -

The Canadian Parliamentary Guide

NUNC COGNOSCO EX PARTE THOMAS J. BATA LI BRARY TRENT UNIVERSITY us*<•-« m*.•• ■Jt ,.v<4■■ L V ?' V t - ji: '^gj r ", •W* ~ %- A V- v v; _ •S I- - j*. v \jrfK'V' V ■' * ' ’ ' • ’ ,;i- % »v • > ». --■ : * *S~ ' iJM ' ' ~ : .*H V V* ,-l *» %■? BE ! Ji®». ' »- ■ •:?■, M •* ^ a* r • * «'•# ^ fc -: fs , I v ., V', ■ s> f ** - l' %% .- . **» f-•" . ^ t « , -v ' *$W ...*>v■; « '.3* , c - ■ : \, , ?>?>*)■#! ^ - ••• . ". y(.J, ■- : V.r 4i .» ^ -A*.5- m “ * a vv> w* W,3^. | -**■ , • * * v v'*- ■ ■ !\ . •* 4fr > ,S<P As 5 - _A 4M ,' € - ! „■:' V, ' ' ?**■- i.." ft 1 • X- \ A M .-V O' A ■v ; ■ P \k trf* > i iwr ^.. i - "M - . v •?*»-• -£-. , v 4’ >j- . *•. , V j,r i 'V - • v *? ■ •.,, ;<0 / ^ . ■'■ ■ ,;• v ,< */ ■" /1 ■* * *-+ ijf . ^--v- % 'v-a <&, A * , % -*£, - ^-S*.' J >* •> *' m' . -S' ?v * ... ‘ *•*. * V .■1 *-.«,»'• ■ 1**4. * r- * r J-' ; • * “ »- *' ;> • * arr ■ v * v- > A '* f ' & w, HSi.-V‘ - .'">4-., '4 -' */ ' -',4 - %;. '* JS- •-*. - -4, r ; •'ii - ■.> ¥?<* K V' V ;' v ••: # * r * \'. V-*, >. • s s •*•’ . “ i"*■% * % «. V-- v '*7. : '""•' V v *rs -*• * * 3«f ' <1k% ’fc. s' ^ * ' .W? ,>• ■ V- £ •- .' . $r. « • ,/ ••<*' . ; > -., r;- •■ •',S B. ' F *. ^ , »» v> ' ' •' ' a *' >, f'- \ r ■* * is #* ■ .. n 'K ^ XV 3TVX’ ■■i ■% t'' ■ T-. / .a- ■ '£■ a« .v * tB• f ; a' a :-w;' 1 M! : J • V ^ ’ •' ■ S ii 4 » 4^4•M v vnU :^3£'" ^ v .’'A It/-''-- V. - ;ii. : . - 4 '. ■ ti *%?'% fc ' i * ■ , fc ' THE CANADIAN PARLIAMENTARY GUIDE AND WORK OF GENERAL REFERENCE I9OI FOR CANADA, THE PROVINCES, AND NORTHWEST TERRITORIES (Published with the Patronage of The Parliament of Canada) Containing Election Returns, Eists and Sketches of Members, Cabinets of the U.K., U.S., and Canada, Governments and Eegisla- TURES OF ALL THE PROVINCES, Census Returns, Etc. -

Colleague, Critic, and Sometime Counselor to Thomas Becket

JOHN OF SALISBURY: COLLEAGUE, CRITIC, AND SOMETIME COUNSELOR TO THOMAS BECKET By L. Susan Carter A DISSERTATION Submitted to Michigan State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of History–Doctor of Philosophy 2021 ABSTRACT JOHN OF SALISBURY: COLLEAGUE, CRITIC, AND SOMETIME COUNSELOR TO THOMAS BECKET By L. Susan Carter John of Salisbury was one of the best educated men in the mid-twelfth century. The beneficiary of twelve years of study in Paris under the tutelage of Peter Abelard and other scholars, John flourished alongside Thomas Becket in the Canterbury curia of Archbishop Theobald. There, his skills as a writer were of great value. Having lived through the Anarchy of King Stephen, he was a fierce advocate for the liberty of the English Church. Not surprisingly, John became caught up in the controversy between King Henry II and Thomas Becket, Henry’s former chancellor and successor to Theobald as archbishop of Canterbury. Prior to their shared time in exile, from 1164-1170, John had written three treatises with concern for royal court follies, royal pressures on the Church, and the danger of tyrants at the core of the Entheticus de dogmate philosophorum , the Metalogicon , and the Policraticus. John dedicated these works to Becket. The question emerges: how effective was John through dedicated treatises and his letters to Becket in guiding Becket’s attitudes and behavior regarding Church liberty? By means of contemporary communication theory an examination of John’s writings and letters directed to Becket creates a new vista on the relationship between John and Becket—and the impact of John on this martyred archbishop. -

Peterborough Heritage Open Days

7TH – 10TH SEPTEMBER 2017 PETERBOROUGH HERITAGE OPEN DAYS incredible venues in and around Peterborough for you to explore, FREE Find out more information at: www.peterboroughcivicsociety.org.uk/heritage-open-days.php PETERBOROUGH HERITAGE OPEN DAYS PETERBOROUGH HERITAGE OPEN DAYS PETERBOROUGH CATHEDRAL, MINSTER PRECINCTS, PETERBOROUGH, PE1 1XS Explore Hidden Spaces… We’re opening up some of our buildings for you to explore, with guides on hand to answer any questions. These are open 11am – 4pm on Saturday 9 September, 12noon – 3pm on Sunday 10 September. Cathedral Library Almoner’s Hall Tucked away above the Cathedral’s 14th century Explore the medieval Almonry and find out porch is our remarkable and unseen library! about the role the abbey played in caring for the (Please note: access via spiral staircase). poor of Peterborough. Knights’ Chamber Inside the Cathedral’s Visitor Centre is the 13th century Knights’ Chamber, a recently restored medieval hall. Medieval costumed guides will be on hand to chat to visitors. Special Guided Tour - Cathedral Taster Tours Table Hall and the Infirmary Find out about the people, events and stories CELEBRATE Discover the remains of the Abbey’s Hospital, that are connected to the Cathedral, a centre including a rare chance to go inside the 15th for Christian worship for over 1300 years with century Table Hall. Tour lasts just over an hour one of our expert tour guides. HERITAGE OPEN DAYS and places are limited (pre-booking strongly Tours last about 45 minutes, meet inside the advised); meet at the Cathedral’s main entrance. Cathedral’s main entrance. Heritage Open Days celebrate England’s fantastic architecture and culture Tours at 11.30am and 2pm on Saturday 9 September, Tours at 11.30am and 2pm on Saturday 9 September by offering free access to properties that are usually closed to the public or 2pm on Sunday 10 September.