All I Really Need to Know I Learned at a Tupperware Party What Tupperware Parties Teach You About Investing and Life

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Winonan - 2000S

Winona State University OpenRiver The inonW an - 2000s The inonW an – Student Newspaper 8-29-2007 The inonW an Winona State University Follow this and additional works at: https://openriver.winona.edu/thewinonan2000s Recommended Citation Winona State University, "The inonW an" (2007). The Winonan - 2000s. 180. https://openriver.winona.edu/thewinonan2000s/180 This Newspaper is brought to you for free and open access by the The inonW an – Student Newspaper at OpenRiver. It has been accepted for inclusion in The inonW an - 2000s by an authorized administrator of OpenRiver. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Volume 86 Issue ■ Remodeling in Maxwell and Somsen halls progress • Freshmen divulge first week terrors and triumphs 'well' place for body and mind Arts A preliminary drawing shows that the Wellness Center will be joined with the existing Memorial Hall at the south end of McCown Gym. ■ Area organiza- Shanthal Perera that would be represented in the new the new center after the final building tions preserve WINONAN building, including the fitness center, plans are approved by the Minnesota State intramurals, athletics, counseling center, Colleges and Universities. Winona's his- After years of simply being an idea, health services and the Health Exercise Schuler was uncertain about how long tory the materialization of Winona State and Rehabilitative Sciences and Physical students will be paying for the building University's wellness and fitness project, Education and Recreation departments. but noted that they are looking into other a combination of services dedicated to The committee also has student avenues besides student tuition to cover 1111 Roberts re- mental and physical health, is gathering representation. -

Karaoke Song Book Karaoke Nights Frankfurt’S #1 Karaoke

KARAOKE SONG BOOK KARAOKE NIGHTS FRANKFURT’S #1 KARAOKE SONGS BY TITLE THERE’S NO PARTY LIKE AN WAXY’S PARTY! Want to sing? Simply find a song and give it to our DJ or host! If the song isn’t in the book, just ask we may have it! We do get busy, so we may only be able to take 1 song! Sing, dance and be merry, but please take care of your belongings! Are you celebrating something? Let us know! Enjoying the party? Fancy trying out hosting or KJ (karaoke jockey)? Then speak to a member of our karaoke team. Most importantly grab a drink, be yourself and have fun! Contact [email protected] for any other information... YYOUOU AARERE THETHE GINGIN TOTO MY MY TONICTONIC A I L C S E P - S F - I S S H B I & R C - H S I P D S A - L B IRISH PUB A U - S R G E R S o'reilly's Englische Titel / English Songs 10CC 30H!3 & Ke$ha A Perfect Circle Donna Blah Blah Blah A Stranger Dreadlock Holiday My First Kiss Pet I'm Mandy 311 The Noose I'm Not In Love Beyond The Gray Sky A Tribe Called Quest Rubber Bullets 3Oh!3 & Katy Perry Can I Kick It Things We Do For Love Starstrukk A1 Wall Street Shuffle 3OH!3 & Ke$ha Caught In Middle 1910 Fruitgum Factory My First Kiss Caught In The Middle Simon Says 3T Everytime 1975 Anything Like A Rose Girls 4 Non Blondes Make It Good Robbers What's Up No More Sex.... -

Robbie Williams

Chart - History Singles All chart-entries in the Top 100 Peak:1 Peak:1 Peak: 53 Germany / United Kindom / U S A Robbie Williams No. of Titles Positions Robert Peter Williams (born 13 February 1974) Peak Tot. T10 #1 Tot. T10 #1 is an English singer-songwriter and entertainer. 1 40 13 3 459 68 8 He found fame as a member of the pop group 1 40 31 7 523 89 11 Take That from 1989 to 1995, but achieved 53 2 -- -- 23 -- -- greater commercial success with his solo career, beginning in 1997. 1 43 32 10 1.005 157 19 ber_covers_singles Germany U K U S A Singles compiled by Volker Doerken Date Peak WoC T10 Date Peak WoC T10 Date Peak WoC T10 1 Freedom 08/1996 10 11 1208/1996 2 16 2 Old Before I Die 04/1997 37 8 04/1997 2 14 2 3 Lazy Days 08/1997 90 1 07/1997 8 8 1 4 South Of The Border 09/1997 14 5 5 Angels 12/1997 9 22 51212/1997 4 42 11/1999 53 19 6 Let Me Entertain You 03/1998 3 15 4 7 Millennium 09/1998 41 9 09/1998 1 1 28 4 06/1999 72 4 8 No Regrets / Antmusic 12/1998 60 10 12/1998 4 19 1 9 Strong 03/1999 45 11 03/1999 4 12 1 10 She's The One / It's Only Us 11/1999 27 15 11/1999 1 1 21 3 11 Rock DJ 08/2000 9 12 2508/2000 1 1 24 12 Kids 10/2000 47 10 10/2000 2 22 3 ► Robbie Williams & Kylie Minogue 13 Supreme 12/2000 14 14 12/2000 4 15 2 14 Let Love Be Your Energy 04/2001 68 3 04/2001 10 16 1 15 Eternity / The Road To Mandalay 07/2001 7 19 4507/2001 1 2 22 16 Somethin' Stupid 12/2001 2 18 1012/2001 1 3 12 4 ► Robbie Williams & Nicole Kidman 17 Mr.Bojangles 03/2002 77 3 18 Feel 12/2002 3 18 8412/2002 4 17 19 Come Undone 04/2003 16 9 04/2003 4 14 1 20 Something Beautiful 07/2003 46 9 08/2003 3 8 2 21 Sexed Up 11/2003 53 10 11/2003 10 9 1 22 Radio 10/2004 2 9 2310/2004 1 1 8 23 Misunderstood 12/2004 20 12 12/2004 8 8 1 24 Tripping 10/2005 1 3 17 7610/2005 2 17 25 Advertising Space 12/2005 10 16 2112/2005 8 11 26 Sin Sin Sin 06/2006 18 16 06/2006 22 7 27 Rudebox 09/2006 1 1 13 5209/2006 4 11 28 Lovelight 11/2006 21 9 11/2006 8 9 1 29 She's Madonna 03/2007 4 18 7 03/2007 16 3 ► Robbie Williams With Pet Shop Boys 30 Close My Eyes 04/2009 33 6 ► Sander Van Doorn vs. -

The Swing Singer

SHANE – THE SWING SINGER Set List Ain't No Sunshine Crazy Little Thing Called Love Heartache Tonight (Bublé) Ain't That a Kick in the Head Crazy Love (Bublé) Hello Young Lovers After the Love Has Gone Cry Me A River Hey, There (Sammy Davis, Jr.) All at Once CuPid Hollywood (Bublé) All at Sea Dance The Night Away Home All by Myself Dance With Me Tonight How Sweet It Is (Bublé) All I Do is Dream Of You (Bublé) All of Me (John Legend) December 1963 (Oh, What a Night!)I Can't StoP Loving You All of Me (Sinatra/Bublé) Don't Get Around Much Anymore I Get The Sweetest Feeling (Cullum) All or Nothing at All Don't Know Why (Norah Jones) I Got It Easy All the Way Don't Rain On My Parade I Left My Heart in San Francisco All You Need is Love Don't Stop Believin' I Need A Dollar Alright, OK, You Win Do Nothin' 'Til You Hear From Me I Only Have Eyes For You Always On My Mind Dream I Put A SPell On You Angels Dream a Little Dream of Me I Won't Dance Another Way to Die Earthquake (Labrynth) I Won't Give UP (Jason Mraz) As Long As I'm Singing Easy I've Got The World On A String As Long As She Needs Me At Last Edge of Something I've Got You Under My Skin At This Moment Embraceable You I'm Your Man (Bublé) Bad, Bad Leroy Brown EmPty Chairs at EmPty Tables I'm Yours Beggin' Endless Night Is This The Way to Amarillo Best of Me Everlasting Love (Jamie Cullum) It Had Better Be Tonight Bewitched, Bothered and Bewildered Everything (Bublé) It Had To Be You Beyond the Sea Everybody Loves Somebody It Must Be Love Birth of the Blues Everybody Needs Somebody It's -

![KARAOKE CATALOGUE: R Artist Song Title R&J Stone We Do It [Duet] R](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/5304/karaoke-catalogue-r-artist-song-title-r-j-stone-we-do-it-duet-r-3705304.webp)

KARAOKE CATALOGUE: R Artist Song Title R&J Stone We Do It [Duet] R

C K A A T R A A L O O K G E U E Songs in English: R KARAOKE CATALOGUE: R Artist Song Title R&J Stone We Do It [Duet] R. B. Greaves Take a Letter Maria R. City ft Adam Levine Locked Away R. City ft Adam Levine Locked Away [Duet] R. Dean Taylor Gotta See Jane R. Dean Taylor Indiana Wants Me R. Dean Taylor There's a Ghost in My House R. Kelly Bad Man R. Kelly Bump n' Grind R. Kelly Feelin' on Yo Booty R. Kelly Feelin' Single R. Kelly Gotham City R. Kelly Hair Braider R. Kelly Happy People R. Kelly I Believe I Can Fly R. Kelly I Can't Sleep Baby R. Kelly I Wish R. Kelly If I Could Turn Back the Hands of Time R. Kelly Ignition R. Kelly Just Like That R. Kelly Lady Sunday R. Kelly Love Letter R. Kelly Only the Loot Can Make Me Happy R. Kelly Radio Message R. Kelly She's Got That Vibe R. Kelly Slow Wind R. Kelly Step in the Name of Love R. Kelly The Storm Is Over Now R. Kelly The World's Greatest R. Kelly Thoia Thoing R. Kelly When a Man Lies R. Kelly When a Woman Loves R. Kelly When a Woman's Fed Up R. Kelly & Celine Dion I'm Your Angel [Duet] R. Kelly & Public Announcement She's Got That Vibe R. Kelly ft Jay-Z and Boo & Gotti Fiesta [Trio] R. Kelly ft Soweto Spiritual Singers Sign of a Victory R.E.M. -

Songs by Title

Songs by Title Title Artist Title Artist #1 Crush Garbage 1990 (French) Leloup (Can't Stop) Giving You Up Kylie Minogue 1994 Jason Aldean (Ghost) Riders In The Sky The Outlaws 1999 Prince (I Called Her) Tennessee Tim Dugger 1999 Prince And Revolution (I Just Want It) To Be Over Keyshia Cole 1999 Wilkinsons (If You're Not In It For Shania Twain 2 Become 1 The Spice Girls Love) I'm Outta Here 2 Faced Louise (It's Been You) Right Down Gerry Rafferty 2 Hearts Kylie Minogue The Line 2 On (Explicit) Tinashe And Schoolboy Q (Sitting On The) Dock Of Otis Redding 20 Good Reasons Thirsty Merc The Bay 20 Years And Two Lee Ann Womack (You're Love Has Lifted Rita Coolidge Husbands Ago Me) Higher 2000 Man Kiss 07 Nov Beyonce 21 Guns Green Day 1 2 3 4 Plain White T's 21 Questions 50 Cent And Nate Dogg 1 2 3 O Leary Des O' Connor 21st Century Breakdown Green Day 1 2 Step Ciara And Missy Elliott 21st Century Girl Willow Smith 1 2 Step Remix Force Md's 21st Century Girls 21st Century Girls 1 Thing Amerie 22 Lily Allen 1, 2 Step Ciara 22 Taylor Swift 1, 2, 3, 4 Feist 22 (Twenty Two) Taylor Swift 10 Days Late Third Eye Blind 22 Steps Damien Leith 10 Million People Example 23 Mike Will Made-It, Miley 10 Seconds Jazmine Sullivan Cyrus, Wiz Khalifa And 100 Years Five For Fighting Juicy J 100 Years From Now Huey Lewis And The News 24 Jem 100% Cowboy Jason Meadows 24 Hour Party People Happy Mondays 1000 Stars Natalie Bassingthwaighte 24 Hours At A Time The Marshall Tucker Band 10000 Nights Alphabeat 24 Hours From Tulsa Gene Pitney 1-2-3 Gloria Estefan 24 Hours From You Next Of Kin 1-2-3 Len Berry 2-4-6-8 Motorway Tom Robinson Band 1234 Sumptin' New Coolio 24-7 Kevon Edmonds 15 Minutes Rodney Atkins 25 Miles Edwin Starr 15 Minutes Of Shame Kristy Lee Cook 25 Minutes To Go Johnny Cash 16th Avenue Lacy J Dalton 25 Or 6 To 4 Chicago 18 And Life Skid Row 29 Nights Danni Leigh 18 Days Saving Abel 3 Britney Spears 18 Til I Die Bryan Adams 3 A.M. -

Major Tool Student Interactive Listening 4Th Ed 071115

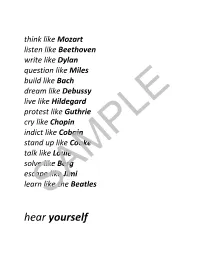

think like Mozart listen like Beethoven write like Dylan question like Miles build like Bach dream like Debussy live like Hildegard protest like Guthrie cry like Chopin indict like Cobain stand up like Cooke talk like Louie solve like Berg escape like Jimi learn likeSAMPLE the Beatles hear yourself Interactive Listening a new approach to music Music Research Journal and iBook companion by Pete Carney and Brian Felix Edited by Susan O’Reilly and Caroline Carriere ©2011, 2012 2014 Peter Carney and Brian Felix SAMPLEChicago, IL interactivelistening.com for a free sample of our interactive digital textbook go to iTunes or our website Created and Printed in the U.S.A. Interactive Listening: A New Approach To Music Published by loopjazz music 9817 S. Wood Street, Chicago, IL 60643 Copyright © 2011, 2012, 2014 by Peter Carney and Brian Felix All rights reserved. International Copyright secured. Fourth edition, 2014 visit us at: interactivelistening.com or email: [email protected] Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Carney, Peter 1974- Felix, Brian 1977- Interactive Listening/ Peter Carney and Brian Felix - 4th edition p. cm. Included bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-0-9833412-1-5 (paperback) 1. Music- History and Criticism 2. Popular music 3. Gospel Music 4. African Music No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recorded, or otherwise, without prior written permission of loopjazz music. SAMPLE For Bridget, Sean and Gavin ‐ Brian For my amazing wife Caroline, Matt man, Pop, Mikey, Susan, Tim, and Mom…the best classroom teacher in the world. -

ARTIST SONG MF CODE TRACK 10000 Maniacs These Are The

ARTIST SONG MF CODE TRACK 10000 Maniacs These Are The Days PI035 2 10cc Donna SF090 15 10cc Dreadlock Holiday SF023 12 10cc I'm Mandy SF079 3 10cc I'm Not In Love SF001 9 10cc Rubber Bullets SF071 1 10cc Things We Do For Love SFMW832 11 10cc Wall Street Shuffle SFMW814 1 1910 Fruitgum Factory Simon Says SFGD047 10 1927 Compulsory Hero SFHH02-5 10 1975 Chocolate SF326 13 1975 City SF329 16 1975 Love Me SF358 13 1975 Robbers SF341 12 1975 Ugh SF360 9 2 Evisa Oh La La La SF114 10 2 Pac California Love SF049 4 2 Unlimited No Limit SFD901-3 11 2 Unlimited No Limits SF006 5 21st Century Girls 21st Century Girls SF140 10 2k Fierce Sweet Love SF159 4 3 S L Take It Easy SF191 9 30 Seconds To Mars Kings And Queens SFMW920 7 30h 3 Feat Katy Perry Starstrukk SF286 11 3oh3 Don't Trust Me SF281 15 3oh3 Feat Ke$ha My First Kiss EZH085 12 3t Anything SF049 2 4 Non Blondes What's Up SFHH02-9 15 411 Dumb SF221 12 411 Teardrops SF225 6 411 And Ghostface On My Knees SF219 4 5 Seconds Of Summer Amnesia SF342 12 5 Seconds Of Summer Don't Stop SF340 17 5 Seconds Of Summer Good Girls SF345 7 5 Seconds Of Summer She Looks So Perfect SF338 5 5 Seconds Of Summer She's Kinda Hot SF355 4 5 Star Rain Or Shine SFMW878 10 50 Cent Candy Shop SF230 10 50 Cent In Da Club SF206 9 50 Cent Just A Lil' Bit SF232 12 50 Cent And Justin Timberlake Ayo Technology EZH067 8 50 Cent And Nate Dogg 21 Questions SF207 4 50 Cent And Ne Yo Baby By Me EZH082 9 50 Cent Feat Eminem And Adam My Life [clean] SF324 6 50 Cent Feat Snoop Dogg And Y Major Distribution (Clean) SF325 13 5th Dimension -

ROBBIE WILLIAMS NACH EINEM SCHEINBAREN Karriere- ● ●●●●●●●●●●●●●●●●●●●●●●●●●●●●●●●● Knick Mit Dem Album «Rudebox» (2006) Ist Er Heute Fleissiger Denn Je

Schweiz am Sonntag, Nr. 45, 10. November 2013 KULTUR | 43 Kaum ein Jahr nach «Take The mit Guy Chambers komponiert – dem Crown» präsentiert Robbie Mann, der seinem Solo-Debüt «Life Thru a Lense» den Schliff verpasste, der ihm Williams schon wieder ein auf Anhieb Erfolg und Respekt eintrug Album. Auf «Swing Both Ways» und ihn zum Superstar machte. «Wir kehrt er zum Swing und hatten immer vor, wieder zusammenzu- Robbie, Robbie noch kommen», sagt Williams. «Damals mach- seinem alten Song-Schreiber Guy Chambers zurück. te es mich fertig, dass rundum alles glaubte, mein Album sei ganz das Werk von Guy und hätte nichts mit mir zu VON HANSPETER KÜNZLER tun. Meiner geistigen Gesundheit zulie- ●●● ● ●●● ● ● ● ● ●●●● ● ● ● ● ●●●● ● ● ● ● ●●●● ● ● ● ● ●●●● ● ● ● ● ●●●● ● ● ● ● ●●●● ● ● ● ● ●●●● ● ● ● ● ●●●● ● ● ● ● ●●●● ● ● ● einmal! be musste ich weg von ihm. Aber es war it 16 ist er bei der Boy- nie als eine ewige Trennung gedacht.» band Take That gelan- det, mit 20 zum Teenie- Für den britischen Superstar schliesst sich mit «Swing Both Ways» ein Kreis «SWINGS BOTH WAYS» ist denn auch Superstar avanciert, nicht einfach Folge zwei von «Swing mit 21 erfolgt der Raus- When You’re Winning», wo sich Robbie Mwurf. Kaum jemand traute dem vor zwölf Jahren zum ersten Mal des charmanten Bühnenhampelmann eine swingenden Erbes von Nat King Cole grosse Karriere zu. und Frank Sinatra annahm. Das stilisti- 18 Jahre später hat sich Robbie Wil- sche Spektrum ist breiter und reicht liams, allen bösen Prognosen zum Trotz, diesmal vom bläsergetriebenen Sou- zur erfolgreichsten Stimme gemausert, thern-Rock von «Shine My Shoes» über ei- die in den letzten zwei Dekaden über den britischen Pop-Horizont gestiegen ● ●●●●●●●●●●●●●●●●●●●●●●●●●●●●●●●● ist. -

Karaoke Catalog Updated On: 17/12/2016 Sing Online on in English Karaoke Songs

Karaoke catalog Updated on: 17/12/2016 Sing online on www.karafun.com In English Karaoke Songs (H?D) Planet Earth My One And Only Hawaiian Hula Eyes Blackout I Love My Baby (My Baby Loves Me) On The Beach At Waikiki Other Side I'll Build A Stairway To Paradise Deep In The Heart Of Texas 10 Years My Blue Heaven What Are You Doing New Year's Eve Through The Iris What Can I Say After I Say I'm Sorry Long Ago And Far Away 10,000 Maniacs When You're Smiling (The Whole World Smiles With Bésame mucho (English Vocal) Because The Night 'S Wonderful For Me And My Gal 10CC 1930s Standards 'Til Then Dreadlock Holiday Let's Call The Whole Thing Off Daddy's Little Girl I'm Not In Love Heartaches The Old Lamplighter The Things We Do For Love Cheek To Cheek Someday You'll Want Me To Want You Rubber Bullets Love Is Sweeping The Country That Old Black Magic (Woman Voice) Life Is A Minestrone My Romance That Old Black Magic (Man Voice) 112 It's Time To Say Aloha I Know Why (And So Do You) DUET Cupid We Gather Together Aren't You Glad You're You Peaches And Cream Kumbaya (I've Got A Gal In) Kalamazoo 12 Gauge The Last Time I Saw Paris My One And Only Highland Fling Dunkie Butt All The Things You Are No Love No Nothin' 12 Stones Smoke Gets In Your Eyes Personality Far Away Begin The Beguine Sunday, Monday Or Always Crash I Love A Parade This Heart Of Mine 1800s Standards I Love A Parade (short version) Mister Meadowlark Home Sweet Home I'm Gonna Sit Right Down And Write Myself A Letter 1950s Standards Home On The Range Body And Soul Get Me To The Church On -

Sister Cities Girlchoir

Occasional Paper Series Volume 2013 Number 30 The Other 17 Hours: Valuing Out-of- Article 10 School Time October 2013 Witnessing the Power of El Sistema in Urban Communities: Sister Cities Girlchoir Erika M. Kitzmiller University of Pennsylvania Follow this and additional works at: https://educate.bankstreet.edu/occasional-paper-series Part of the Interpersonal and Small Group Communication Commons, Music Education Commons, and the Women's Studies Commons Recommended Citation Kitzmiller, E. M. (2013). Witnessing the Power of El Sistema in Urban Communities: Sister Cities Girlchoir. Occasional Paper Series, 2013 (30). Retrieved from https://educate.bankstreet.edu/occasional-paper- series/vol2013/iss30/10 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Educate. It has been accepted for inclusion in Occasional Paper Series by an authorized editor of Educate. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Witnessing the Power of El Sistema in Urban Communities: Sister Cities Girlchoir Erika Kitzmiller On December 5th 2013, the Sister Cities Girlchoir members gathered for a performance at the Union League, a famed elite social and philanthropic club in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. The girls wore their school uniforms to identify their respective schools and sported white carnation boutonnieres to show that they were all members of the same ensemble. Several family members were there to see the performance. For many of the girls, this was the first time that they were performing in such an austere space with choir members from another school. When the girls entered the building, with its crystal chandeliers, hand-carved mahogany staircases, and antique silk curtains, many of them remarked that they had never seen anything so beautiful. -

Unpublished United States Court of Appeals for The

UNPUBLISHED UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS FOR THE FOURTH CIRCUIT SHEILA PATTERSON, Plaintiff-Appellant, v. No. 99-1738 COUNTY OF FAIRFAX, VIRGINIA; THE BOARD OF COUNTY SUPERVISORS, Defendants-Appellees. Appeal from the United States District Court for the Eastern District of Virginia, at Alexandria. Claude M. Hilton, Chief District Judge. (CA-93-788-A) Argued: January 24, 2000 Decided: May 18, 2000 Before MICHAEL and TRAXLER, Circuit Judges, and John T. COPENHAVER, Jr., United States District Judge for the Southern District of West Virginia, sitting by designation. _________________________________________________________________ Affirmed by unpublished opinion. Judge Traxler wrote the majority opinion, in which Judge Copenhaver joined. Judge Michael wrote a dissenting opinion. _________________________________________________________________ COUNSEL ARGUED: Claude David Convisser, CLAUDE D. CONVISSER & ASSOCIATES, P.C., Alexandria, Virginia, for Appellant. Cynthia Lee Tianti, Assistant County Attorney, Fairfax, Virginia, for Appel- lees. ON BRIEF: David P. Bobzien, County Attorney, Robert Lyn- don Howell, Deputy County Attorney, Fairfax, Virginia, for Appellees. _________________________________________________________________ Unpublished opinions are not binding precedent in this circuit. See Local Rule 36(c). _________________________________________________________________ OPINION TRAXLER, Circuit Judge: Sheila Patterson ("Patterson") appeals from a grant of summary judgment in favor of the County of Fairfax ("the County") on her Title VII hostile work environment claim. We affirm. I. The County hired Patterson, an African-American woman, as a police officer in November 1983. Patterson filed suit in 1993 against her employer alleging a bevy of wrongs. Over the course of this liti- gation, this court has affirmed grants of summary judgment on Patter- son's claims of discriminatory failure to promote, discriminatory denial of training opportunities, discriminatory application of disci- plinary proceedings, and retaliation.