Asian Modernisms | Michelle Lim Seok Ling

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

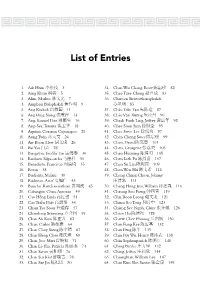

List of Entries

List of Entries 1. Aik Htun 3 34. Chan Wai Chang, Rose 82 2. Aing Khun 5 35. Chao Tzee Cheng 83 3. Alim, Markus 7 36. Charoen Siriwatthanaphakdi 4. Amphon Bulaphakdi 9 85 5. Ang Kiukok 11 37. Châu Traàn Taïo 87 6. Ang Peng Siong 14 38. Châu Vaên Xöông 90 7. Ang, Samuel Dee 16 39. Cheah Fook Ling, Jeffrey 92 8. Ang-See, Teresita 18 40. Chee Soon Juan 95 9. Aquino, Corazon Cojuangco 21 41. Chee Swee Lee 97 10. Aung Twin 24 42. Chen Chong Swee 99 11. Aw Boon Haw 26 43. Chen, David 101 12. Bai Yao 28 44. Chen, Georgette 103 13. Bangayan, Teofilo Tan 30 45. Chen Huiming 105 14. Banharn Silpa-archa 33 46. Chen Lieh Fu 107 15. Benedicto, Francisco 35 47. Chen Su Lan 109 16. Botan 38 48. Chen Wen Hsi 111 17. Budianta, Melani 40 49. Cheng Ching Chuan, Johnny 18. Budiman, Arief 43 113 19. Bunchu Rotchanasathian 45 50. Cheng Heng Jem, William 116 20. Cabangon Chua, Antonio 49 51. Cheong Soo Pieng 119 21. Cao Hoàng Laõnh 51 52. Chia Boon Leong 121 22. Cao Trieàu Phát 54 53. Chiam See Tong 123 23. Cham Tao Soon 57 54. Chiang See Ngoh, Claire 126 24. Chamlong Srimuang 59 55. Chien Ho 128 25. Chan Ah Kow 62 56. Chiew Chee Phoong 130 26. Chan, Carlos 64 57. Chin Fung Kee 132 27. Chan Choy Siong 67 58. Chin Peng 135 28. Chan Heng Chee 69 59. Chin Poy Wu, Henry 138 29. Chan, Jose Mari 71 60. -

Download Singapore Portraits Educators Guide For

Singapore Portraits Let The Photos Tell The Story Singapore Portraits is a tribute to some of Singapore’s most creative personalities. It features the works of and interviews with local artists which together tell the story of Singapore through their words and images. Besides the paintings and photographs, write-ups detailing the background of the artwork, social and historical contexts and artist biographies are also included. < for Primary School Students> Educators’ Guide Education and Community Outreach Division SG Portraits About The Exhibition Generations of Singapore artists and photographers have expressed themselves through art, telling stories of our nation, our history, people and their ways of lives. This exhibition looks at how Singapore has inspired art-making and what stories art tells about Singapore. Art in Singapore Drawn by the prospect of work in the region’s new European settlements, artists began to arrive here as early as the late 18th century. By the early 20th century, immigrant artists were forming art societies and the first school in Singapore, the Nanyang Academy of Fine Arts, was established in 1938. Among the most significant artists from the pioneering generation were Cheong Soo Pieng, Chen Chong Swee, Liu Kang, Chen Wen His, Georgette Chen and Lim Cheng Hoe. They were instrumental in establishing the Nanyang Style, the first local art style that emerged in the 1950s. Their work influenced younger generations of artists who followed in their footsteps to explore fresh ways of expressing local identity and local relevancy through their art. Take some time to share with students the importance of appreciating Art and the Arts that can help in their overall development. -

Associate Artistic Director, Theatreworks, Singapore Associate Artist, the Substation, Singapore

Associate Artistic Director, Theatreworks, Singapore Associate Artist, The Substation, Singapore vertical submarine is an art collective from Singapore that consists of Joshua Yang, Justin Loke and Fiona Koh (in order of seniority). According to them, they write, draw and paint a bit but eat, drink and sleep a lot. Their works include installations, drawings and paintings which involve text, storytelling and an acquired sense of humour. In 2010, they laid siege to the Singapore Art Museum and displayed medieval instruments of torture including a fully functional guillotine. They have completed projects in Spain, Taiwan, Hong Kong, Korea, The Philippines, Mexico City, Australia and Germany. Collectively they have won several awards including the Credit Suisse Artist Residency Award 2009, The President’s Young Talents Award 2009 and the Singapore Art Show Judges’ Choice 2005. They have recently completed a residency at Gertrude Contemporary in Melbourne. MERITS 2009 President’s Young Talents 2009 Credit Suisse Art Residency Award 2005 Singapore Art Show 2005: New works, Judge’s Choice 2004 1st Prize - Windows @ Wisma competition, Wisma Atria creative windows display PROJECTS 2011 Incendiary Texts, Richard Koh Fine Art, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia Dust: A Recollection, Theatreworks, Singapore Asia: Looking South, Arndt Contemporary Art, Berlin, Germany Postcards from Earth, Objectifs – Center for Photography and Filmmaking, Singapore Open Studios, Gertrude Contemporary, Melbourne, Australia Art Stage 2011, Marina Bay Sands, Singapore 2010 How -

Brother Joseph Mcnally P

1 Design Education in Asia 2000- 2010 Exploring the impact of institutional ‘twinning’ on graphic design education in Singapore Simon Richards Z3437992 2 3 Although Singapore recently celebrated 50 years of graphic design, relatively little documentation exists about the history of graphic design in the island state. This research explores Singaporean design education institutes that adopted ‘twinning’ strategies with international design schools over the last 20 years and compares them with institutions that have retained a more individual and local profile. Seeking to explore this little-studied field, the research contributes to an emergent conversation about Singapore’s design history and how it has influenced the current state of the design industry in Singapore. The research documents and describes the growth resulting from a decade of investment in the creative fields in Singapore. It also establishes a pattern articulated via interviews and applied research involving local designers and design educators who were invited to take part in the research. The content of the interviews demonstrates strong views that reflect the growing importance of creativity and design in the local society. In considering the deliberate practice of Singaporean graphic design schools adopting twinning strategies with western universities, the research posits questions about whether Singapore is now able to confirm that such relationships have been beneficial as viable long-term strategies for the future of the local design industry. If so, the ramifications may have a significant impact not only in Singapore but also in major new education markets throughout Asia, such as the well-supported creative sectors within China and India. -

The Artistic Adventure of Two Bali Trips, 1952 and 2001

Wang Ruobing The Quest for a Regional Culture: The Artistic Adventure of Two Bali Trips, 1952 and 2001 Left to right: Liu Kang, Cheong Soo Pieng, Luo Ming, Ni Pollok, Adrien-Jean La Mayeur, Chen Chong Swee, Chen Wen Hsi, 1952. Courtesy of Liu Kang Family. iu Kang (1911–2004), Chen Wen Hsi (1906–1991), Cheong Soo Pieng (1917–83), and Chen Chong Swee (1910–1986) are four Limportant early artists of Singapore. They were born in China and emigrated to what was then called Malaya before the founding of the People’s Republic of China.1 In 1952, these four members of the Chinese diaspora went to Bali for a painting trip. Struck by the vibrant scenery and exoticism of Balinese culture, on their return they produced from their sketches a significant amount of artwork that portrayed the primitive and pastoral Bali in a modernist style, and a group exhibition entitled Pictures from Bali was held a year later at the British Council on Stamford Road in Singapore. This visit has been regarded as a watershed event in Singapore’s art history,2 signifying the birth of the Nanyang style through their processing of Balinese characteristics into a unique “local colour”—an aesthetic referring to a localized culture and identity within the Southeast Asian context. Their Bali experience had great significance, not only for their subsequent artistic development, both as individuals and as a group, but also for the stylistic development of Singaporean artists who succeeded them.3 Vol. 12 No. 5 77 Exhibition of Pictures from Bali, British Council, Singapore, 1953. -

Chinese Diaspora and the Emergence of Alternative Modernities in Malaysian Visual Arts

2011 International Conference on Humanities, Society and Culture IPEDR Vol.20 (2011) © (2011) IACSIT Press, Singapore Chinese Diaspora and the Emergence of Alternative Modernities in Malaysian Visual Arts Kelvin Chuah Chun Sum1, Izmer Ahmad2 and Emelia Ong Ian Li3 1,2,3Ph.D. Candidate. School of Arts. Universiti Sains Malaysia. Abstract. This paper investigates the early history of modern Malaysian art as evidence of alternative modernism. More specifically, we look at the Nanyang artists as representing a particular section of early modern Malaysian art whose works propose a particular brand of modernism that is peculiar to this region. These artists were formally trained in the tenets of both Western and Chinese art and transplanted into Malaya in the early 20th century. Consequently, their artistic production betrays subject matters derived from diverse travels, resulting unique stylistic hybridization that is discernible yet distinctive of the Malayan region of Southeast Asia. By positioning their art within the problematic of the modern we argue that this stylistic innovation exceeds the realm of aesthetics. Rather, it weaves a particular social and historical discourse that elucidates the Malayan experience and production of modernity. The art of Nanyang must therefore be understood as a local artifact within the global archaeology of alternative modernism. It is a site where modernity as a plural and culturally-situated phenomenon can be continually historicized and articulated in context. Research methods comprise a combination of archival research, field research which includes viewing the actual artwork as well as interviews with pertinent experts within the area such as the artists themselves, friends of the artists, art writers, historians and curators. -

Annual Report

ANNUAL REPORT FY2017/2018 主席献词 01 Chairman’s Message 03 总裁献词 目 CEO’s Message 05 赞助人和董事会 愿景 录 Patron & Board of Directors 多元种族 .和谐社会 09 董事委员会 华族文化 .本土丰彩 CONTENTS Board Committees 11 年度活动 VISION Highlights of the Year A vibrant Singapore Chinese culture, 47 我们的设施 rooted in a cohesive, multi-racial society Our Facilities 捐款人 55 Our Donors 宗旨 57 我们的团队 发展本土华族文化,承先启后; Our Team 开 展 多 元 文 化 交 流 ,促 进 社 会 和 谐 财务摘要 59 Financial Highlights MISSION 机构信息 Nurture Singapore Chinese culture 61 Corporate Information and enhance social harmony 01 02 2017/2018年对我们来说是个具有重要 为 了 注 入 更 多 活 力 予 本 地 华 族 文 化 ,中 We look back on a most memorable year in 2017/2018, the Duanwu Festival, Mid-Autumn under the Stars for the Mid- 主席献词 意义的一年。2017年5月19日 ,新 加 坡 心 开 幕 后 推 出 的《 新 •创 艺 》特 展 ,汇 集 key highlight being the official opening of the Singapore Autumn Festival; and held the Spring Reception, as well as 华族文化中心在万众期待中由李显龙 了19名本地艺术家共21件作品,并通过 Chinese Cultural Centre (SCCC) on 19 May 2017, graced our first Lunar New Year Carnival & Concert to usher in the CHAIRMAN’S 总理主持开幕。这栋位于珊顿道金融中 这一批年轻艺术家的视角,重新诠释新 by the presence of our Patron, Prime Minister Lee Hsien Year of the Dog. These festive events were well-attended by 心的11层崭新大楼,为本地的文化团体 加坡华族文化的意涵。 Loong. The much-anticipated opening was held with great invited guests and members of the community who enjoyed fanfare. This new 11-storey building located in the heart the performances and special activities. -

KLAS Art Auction

KUALA LUMPUR, Sunday 26 JUNE 2016 KLAS Art Auction Malaysian modern & contemporary art Lot 38, Abdul Latiff Mohidin, Pago-Pago Sculpture, 1970 KLAS Art Auction 2016 Malaysian modern & contemporary art Edition XXI Auction Day Sunday, 26 June 2016 1.00 pm Registration & Brunch Starts 11.30 am Artworks Inspection From 11.30 am onwards Clarke Ballroom Level 6 Le Meridien Kuala Lumpur 2 Jalan Stesen Sentral 50470 Kuala Lumpur Supported by Lot 63, Siew Hock Meng, Far Away, 1989 KL Lifestyle Art Space c/o Mediate Communications Sdn Bhd 31, Jalan Utara 46200 Petaling Jaya Selangor t: +603 7932 0668 f: +603 7955 0168 e: [email protected] Contact Information Auction enquiries and condition report Lydia Teoh +6019 2609668 [email protected] Datuk Gary Thanasan [email protected] Payment and collection Shamila +6019 3337668 [email protected] Lot 36, Awang Damit Ahmad, Marista “Pun-Pun dan Biangsung”, 1998 Kuala Lumpur Full Preview Date: 16 June - 25 June 2016 Venue: KL Lifestyle Art Space 31, Jalan Utara 46200 Petaling Jaya Selangor, Malaysia Auction Day Date: Sunday, 26 June 2016 Venue: Clarke Ballroom Level 6 Le Meridien Kuala Lumpur 2 Jalan Stesen Sentral 50470 Kuala Lumpur Malaysia Time: 1.00 pm Map to KLAS @ Jalan Utara Lot 36, Awang Damit Ahmad, Marista “Pun-Pun dan Biangsung”, 1998 5 Lot 28, Abdul Latiff Mohidin, Gelombang Rimba, 1995 Contents Auction Information 5 Glossary 9 Lot 1 - 83 20 Auction Terms and Conditions 146 Index of Artists 160 Lot 2, Ismail Latiff, Tioman Tioman..Bay Moon Fantasy, 1994 Glossary 6 AWANG DAMIT AHMAD 1 KHALIL IBRAHIM E.O.C “SISA SEmusim”, 1994 EAST COAST SERIES, 1992 Mixed media on canvas 76 x 61 cm Acrylic on canvas 43 x 24 cm RM 45,000 - RM 80,000 RM 6,500 - RM 9,500 2 ISMAIL LATIFF 7 KHALIL IBRAHIM TIOMAN TIOMAN. -

Artists Imagine a Nation

ARTISTS IMAGINE A NATION Abdullah Ariff Boo Sze Yang Chen Cheng Mei (aka Tan Seah Boey) Chen Shou Soo Chen Wen Hsi Cheong Soo Pieng Chia Yu Chian Chng Seok Tin Choo Keng Kwang Chuah Thean Teng Chua Mia Tee Foo Chee San Ho Khay Beng Khaw Sia Koeh Sia Yong Kuo Ju Ping Lee Boon Wang Lee Cheng Yong Lim Mu Hue Lim Tze Peng Mohammad Din Mohammad Ng Eng Teng Ong Kim Seng Tumadi Patri Phua Cheng Phue Anthony Poon Seah Kim Joo Tang Da Wu Tay Bak Koi Tay Boon Pin Teo Eng Seng Tong Chin Sye Wee Beng Chong Wong Shih Yaw Yeh Chi Wei Yong Mun Sen Contents Foreword Bala Starr 8 Pictures of people and places Teo Hui Min 13 Catalogue of works 115 Brief artists’ biographies 121 Acknowledgements 135 Foreword Works of art are much more than simple collectables or trophies, in the A work of art maintains its status as a speculative object well past the date same way that history is more than a compilation of triumphal stories or nostalgic the artist considered it ‘finished’ or resolved, and in fact meanings might never reflections. Histories build and change through their own telling. The works in actually fix or settle. What we identify ascontemporary is as much about a process this exhibition, Artists imagine a nation, record individual artists’ perceptions, of looking back and re-evaluating the practices and insights of those who have experiences and thinking, and document their aspirations for their communities travelled before us as it is about constantly seeking the new. -

Soo Pieng: Master of Composition

Press Release Soo Pieng: Master of Composition 19 Jan – 9 Mar 2019 Opening: Friday 18 January, 6.30pm – 8.30pm Guest-of-Honour: Mr Edmund Cheng Chairman of Singapore Art Museum Blue Atmosphere, 1966, Oil on canvas, 70 x 105.5 x 3 cm Modern master Cheong Soo Pieng kicks off Singapore Art Week 2019 at STPI. For the very first time, the artist’s ingenious approach to composition and materiality is examined, highlighting his artistic breadth and depth in an unprecedented manner through fifty- two exemplary paintings, sculptures and works on paper which feature Chinese ink, oil, and metal amongst other materials. Gleaned from important private collections, the show provides a definitive selection of some of Soo Pieng’s most seminal creations. In review are both popular favourites and newly-revealed masterpieces that allow fresh considerations of some of the artist’s most important achievements – the subject of the personality of the people of Southeast Asia, the re-creation of the Chinese-styled landscape, and Soo Pieng’s development of modern abstraction. With attention to the artist’s innovative composing processes, Untitled (1960) highlights deeply ethnocultural overlays in Southeast Asia; it features his depiction of human figures situated within a local domestic scene with a stylized body language. Blue Atmosphere, 1966, is an abstract impressionist masterpiece based on natural phenomena–it is a testament to the artist’s emotional and intelligent choices in material and colour. The artist’s Untitled series of metal reliefs are also masterful configurations where elements of landscape painting are revealed, particularly through the use of horizon lines that cut across the picture and the suggestions of structural forms. -

A Story of Singapore Art

artcommune gallery proudly presents A Story of Singapore Art An art feast that captures a uniquely modern Singapore cross-fertilized by decades of East- West sensibility in fine art. A Brief Overview The story of Singapore art could be said to have first taken roots when the island flourished as a colonial port city under the British Empire. In addition to imported labourers from India and China, unrest and destitution brought on by civil conflicts and the great world wars culminated to a significant exodus of Chinese intellectuals (educators, scholars, writers and painters) and businessmen to Singapore in search of better work-life opportunities. By the early-20th century, Singapore (then still part of the Straits Settlements) was already a melting pot of diverse migrant traditions and cultures; the early Singapore art scene was naturally underpinned by these developments. During this period, most schools under the British Colonial system taught watercolour, charcoal and pastel lessons under its main art scheme while the more distinguished Chinese language-based schools such as Chinese High School often taught a combination of Western oil and Chinese ink paintings (in fact, a number of these Chinese art teachers were previously exposed to the Paris School of Art and classical Chinese painting during their art education in China in the 1920s). Furthermore, art societies including United Artists Malaysia as well as the Society of Chinese Artists were in place in as early as the 1930s, and the Nanyang Academy of Fine Arts (NAFA) was formally established by Chinese artist-educator Lim Hak Tai in 1938. To paint a simplified picture: the local art production in early Singapore may be broadly characterised into three veins – the traditional Chinese painting, the Nanyang style, and British watercolour style. -

Nanyang Style - Singapore's Pioneer Art Movement

Jul 12, 2011 14:35 +08 Nanyang Style - Singapore's Pioneer Art Movement Singapore was known as Nanyang in the late 18th century. Representing South Seas in Chinese, Nanyang was a goldmine for many Chinese immigrants. Art was denied progression during this period of colonial rule. The first nationwide art class was also implemented reluctantly to comply with British examination standards. So what is the Nanyang style? Who are the main artists? This article will attempt to address these questions. According to the definition from Singapore Art Museum, Nanyang style integrates teachings from Western schools of Paris and Chinese painting traditions, depicting local or Southeast Asian subject matters. Most Nanyangpaintings are either Chinese ink or oil on canvas. There was a great influx of Chinese immigrants and the emergence of Nanyang style was in response to the dichotomy of Chinese nationalism and Southeast Asian regionalism. Colonial rule restricted art development and it was only in the 19th century when the first art society started – The Amateur Drawing Association. While in Kuala Lumpur, United Artists Malaysia emerged. These societies imparted mainly Chinese influences in the Nanyang style. As global economies were recovering from Great Depression, artists of the Nanyang style were benefiting from extra exposure from art trends in Europe and China. The establishment of Society of Chinese Artists in 1935 had members who were not only alumni of Chinese art academies but were also avid fans of western art. The need to craft a unique identity was stronger after World War II, amidst growing anti-colonial sentiments. Founding artists wanted to portray Nanyang culture in a visually unique flavour.