Full Text-PDF

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

(F) 0364- 2223394 EAST KHASI HILLS DISTRICT SHILLONG No

GOVERNMENT OF MEGHALAYA (O) 0364-2224003/2500782 OFFICE OF THE DEPUTY COMMISSIONER (F) 0364- 2223394 EAST KHASI HILLS DISTRICT SHILLONG No. DDMA/EKH/152/2020/ ` Dated Shillong, the 20th May, 2021 Press Release In pursuance to Health Department Advisory for decentralizing of Covid – 19 Management No.Health.21/2020/Pt.VIII/93, dated 15/05/2021, dedicated War Rooms have been set up in each of the Zones in Shillong Urban Agglomeration/C &RD Blocks under East Khasi Hills. The general public are requested to contact the War Room Number assigned to the Zones under which their place of residence falls for any Covid – 19 related assistance. This arrangement is put in place so as to ensure quick and timely response to any Covid – 19 related requirements of the public in these respective areas particularly for reporting sickness, symptoms, requirement of beds, etc. Each War Roomwill be headed by the Incident Commanders/Zonal Magistrate and the Medical Officer concerned. War Room Number to be SL. NO Name of the Zone / Area / C &RD Block allotted 1 Zone I (Areas under Laitumkhrah Police Station) 6009311101 2 Zone II (Areas under Laban Police Station) 6009311102 3 Zone III (Areas under Sadar Police Station) 6009311103 4 Zone III (Areas under Pasteur Beat House) 6009311104 5 Zone IV (Areas under Lumdiengjri Police Station) 6009311105 Zone V (Areas under Rynjah Police Station &Mawpat 6 6009311106 Block) 7 Zone VI (Areas under Madanrting Police Station) 6009311107 Zone VII (Areas under Mawlai Police Station &Mawlai 8 6009311108 Block) 9 Mylliem Block 6009311109 10 Mawphlang Block 6009311120 11 KhatarshnongLaitkroh Block 6009311121 12 Shella – Bholaganj Block 6009311123 13 Mawsynram Block 6009311124 14 Mawryngkneng Block 6009311125 15 Sohiong Block 6009311126 16 Pynursla Block 6009311127 17 Mawkynrew Block 6009311128 Attached is list of all the Zones and localities assigned thereunder for Shillong Urban Agglomeration. -

Meghalaya S.No

Meghalaya S.No. District Name of the Establishment Address Major Activity Description Broad NIC Owner Emplo Code Activit ship yment y Code Code Class Interva l 107C.M.C.L STAR CEMENT 17 LUMSHNONG, JAINTIA FMANUFACTURE OF 06 325 4 >=500 INDUSTRIES LTD HILLS 793200 CEMENT 207HILLS CEMENTS 11 MYNKRE, JAINTIA MANUFACTURE OF 06 239 4 >=500 COMPANY INDUSTRIES HILLS 793200 CEMENT LIMITED 307AMRIT CEMENT 17 UMLAPER JAINTIA -MANUFACTURE OF 06 325 4 >=500 INDUSTRIES LTD HILLS 793200 CEMENT 407MCL TOPCEM CEMENT 99 THANGSKAI JAINTIA MANUFACTURE OF 06 239 4 >=500 INDUSTRIES LTD HILLS 793200 CEMENT 506RANGER SECURITY & 74(1) MAWLAI EMPLOYMENT SERVICE 19 781 2 >=500 SERVICE ORGANISATION, MAWAPKHAW, SHILLONG,EKH,MEGHALA YA 793008 606MEECL 4 ELECTRICITY SUPPLIER 07 351 4 >=500 LUMJINGSHAI,POLO,SHILL ONG,EAST LAWMALI KHASI HILLS,MEGHALAYA 793001 706MEGHALAYA ENERGY ELECTRICITY SUPPLY 07 351 4 >=500 CORPORATION LTD. POLO,LUMJINGSHAI,SHILL ONG,EAST KHASI HILLS,MEGHALAYA 793001 806CIVIL HOSPITAL 43 BARIK,EAST KHASI HOSPITAL 21 861 1 >=500 SHILLONG HILLS,MEGHALAYA 793004 906S.S. NET COM 78(1) CLEVE COLONY, INFORMATION AND 15 582 2 200-499 SHILLONG CLEVE COMMUNICATION COLONY EAST KHASI HILLS 793001 10 06 MCCL OFFICE SOHSHIRA 38 BHOLAGANJ C&RD MANUFACTURE OF 06 239 4 200-499 MAWMLUH SHELLA BLOCK EAST KHASI HI CEMENT MAWMLUH LLS DISTRICT MEGHALAYA 793108 11 06 MCCL SALE OFFICE MAWMLUH 793108 SALE OFFICE MCCL 11 466 4 200-499 12 06 DR H.GORDON ROBERTS 91 JAIAW HOSPITAL HEALTH 21 861 2 200-499 HOSPITAL PDENG,SHILLONG,EAST SERVICES KHASI HILLS,MEGHALAYA 793002 13 06 GANESH DAS 47 SHILLONG,EAST KHASI RESIDENTIAL CARE 21 861 1 200-499 HOSPITAL,LAWMALI HILLS MEGHALAYA ACTIVITIES FORWOMEN 793001 AND CHILDREN 14 06 BETHANY HOSPITAL 22(3) NONGRIM HOSPITAL 21 861 2 200-499 HILLS,SHILLONG,EAST KHASI HILLS,MEGHALAYA 793003 15 06 GENERAL POST OFFICE 12 KACHERI ROAD, POSTAL SERVICES 13 531 1 200-499 SHILLONG KACHERI ROAD EAST KHASI HILLS 793001 16 06 EMERGENCY 19(1) AMBULANCE SERVICES. -

Carbonizing Forest Governance

Invitation Carbonizing forest governance forest Carbonizing You are cordially invited to attend the public defense of my PhD thesis, entitled: Carbonizing forest Carbonizing forest governance: governance: Analyzing the consequences of REDD+ for multilevel Analyzing the consequences of REDD+ forest governance for multilevel forest governance On Tuesday 5 april 2016 at 1.30 p.m. in the Aula Marjanneke J. Vijge of Wageningen University (Generaal Foulkesweg 1a) The ceremony will be followed by a reception Marjanneke Vijge [email protected] Marjanneke Marjanneke J. Vijge Paranymphs: Judith Floor (+31613098619) [email protected] Lotte Vijge [email protected] Carbonizing forest governance: Analyzing the consequences of REDD+ for multilevel forest governance Marjanneke J. Vijge Thesis committee Promotor Prof. Dr A.P.J. Mol Professor of Environmental Policy Wageningen University Co-promotor Dr A. Gupta Associate professor, Environmental Policy Group Wageningen University Other members Prof. Dr M.N.C. Aarts, Wageningen University Prof. Dr B.J.M. Arts, Wageningen University Prof. Dr J. Gupta, University of Amsterdam Prof. Dr M. Lederer, Westfälische Wilhelms-Universität Münster, Germany This research was conducted under the auspices of Wageningen School of Social Sciences (WASS). Carbonizing forest governance: Analyzing the consequences of REDD+ for multilevel forest governance Marjanneke J. Vijge Thesis submitted in fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of doctor at Wageningen University by the authority of the Rector Magnificus Prof. Dr A.P.J. Mol, in the presence of the Thesis Committee appointed by the Academic Board to be defended in public on Tuesday 5 April 2016 at 1.30 p.m. in the Aula. -

East Khasi Hills District, Meghalaya

GOVERNMENT OF INDIA MINISTRY OF WATER RESOURCES CENTRAL GROUND WATER BOARD GROUND WATER INFORMATION BOOKLET EAST KHASI HILLS DISTRICT, MEGHALAYA North Eastern Region Guwahati September, 2013 GROUND WATER INFORMATION BOOKLET EAST KHASI HILLS DISTRICT, MEGHALAYA DISTRICT AT A GLANCE Sl. ITEMS STATISTICS No. 1. GENERAL INFORMATION i) Geographical area (Sq km) 2748 ii) Administrative Divisions 8 (Mylliem, Mawryngkneng, Pynursla, Mawphlang, Number of Blocks Mawkynrew, Shella-Bholaganj, Mawsynram, Khatarshnong-Laitkroh ) Number of Villages 975 (including about 28 uninhabited villages) Towns 2 (Statutory Towns) / 11 Census Towns iii) Population ((Provisional) (2011 census) Total Population 824,059 (Decadal Growth 2001-2011 24.68%) Rural Population 458,010 (Decadal Growth 2001-2011 19.53%) Urban Population 366,049 (Decadal Growth 2001-2011 31.79%) iv) Average annual rainfall (mm) 1600-12000, Mawsynram & Cherrapunjee are the Source: Directorate of Agriculture, Meghalaya. world’s wettest places with an average annual rainfall of about 12000 mm. 2. GEOMORPHOLOGY Major physiographic units Denudational High & Low Hills, dissected plateau with deep gorges Major Drainages Umtrew, Umiam, Um Khen, Um Song, Umngot, Umngi, Um Sohryngkew, Um Krem etc 3. LAND USE (Sq Km) 2010-11 a) Forest area 1067.52 b) Net area sown 377.85 c)Total Cropped area 456.26 4. MAJOR SOIL TYPES a) Red loamy soil b) Lateritic soil 5. AREA UNDER PRINICIPAL CROPS (as Kharif: Rice:56.83, Maize:20.05, Oilseeds:2.25 on 2010-11, in sq Km) Rabi : Rice:1.11, Millets:1.84, Pulses:2.87, Source: Directorate of Agriculture, Meghalaya. Oilseeds:1.16 6. IRRIGATION BY DIFFERENT SOURCES a. Surface water, command area (Ha) 3347 b. -

Mawsynram Declaration

Case Study on Mawsynram Declaration Written by KM Unit, East Khasi Hills District Project Management Unit, Community Led Landscape Management Project (CLLMP) TABLE OF CONTENTS Abstract ……………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………3 The Mawsynram Declaration ……………………………………………………………..……………………………………………4 Outomce/Discussion……………………………………………….………………………………………………………………..…..5-7 Future…………………..…………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………..8 2 Abstract Mawsynram is a village located on the southern hillocks of East Khasi Hills district in the state of Meghalaya, North East of India. Located at a distance of 65 kilometers from state capital, Shillong, Mawsynram is famed to have the highest average rainfall on Earth. Perched atop a ridge, the village receives an average of 467 inches of rain per year (as per Meteorological sources). The heavy rainfall is attributed to air currents sweeping over the steaming floodplains of Bangladesh, gathering moisture as they move north. When the resulting clouds hit the steep hills of Meghalaya they are percolated or squeezed through the narrowed gap in the atmosphere and compressed to the stage they can no longer hold their moisture, causing the near constant rain the village is famous for. The people in and around Mawsynram are dependent on agriculture for their livelihood. In conjunction the Central Government’s MGNREGA is also working and has greatly aided in creating durable assets and providing an employment avenue for the people in this region. In spite of the village’s status as the wettest place on earth, it ironically suffers water shortages especially in the winter months. This can be attributed to a number of causes most notably the lack of infrastructures related to water conservation and retention as well as severe deforestation in some parts of the region. -

RETHINKING REDD+ a Centre for Science and Environment Assessment

A CENTRE FOR SCIENCE AND ENVIRONMENT ASSESSMENT RETHINKING REDD+ A Centre for Science and Environment assessment Centre for Science and Environment Research director: Chandra Bhushan Writers: Shruti Agarwal, Ajay Kumar Saxena, Vivek Vyas and Soujanya Shrivastava Editor: Arif Ayaz Parrey Design: Ajit Bajaj Layout: Kirpal Singh Cover design: Ritika Bohra Production: Rakesh Shrivastava and Gundhar Das We are grateful to the Swedish International Development Cooperation Agency (SIDA) for its institutional support Bread for the World—Protestant Development Service The document has been produced with the financial contribution of Bread for the World— Protestant Development Service and Swedish International Development Cooperation Agency. The views herein shall not necessarily be taken to reflect the official opinion of the donor. © 2018 Centre for Science and Environment Material from this publication can be used, but with acknowledgement. Maps in this report are not to scale. Citation: Shruti Agarwal, Ajay Kumar Saxena, Vivek Vyas and Soujanya Shrivastava, 2018, Rethinking REDD+: A CSE assessment, Centre for Science and Environment, New Delhi Published by Centre for Science and Environment 41, Tughlakabad Institutional Area New Delhi 110 062 Phone: 91-11-40616000 Fax: 91-11-29955879 E-mail: [email protected] CONTENTS Foreword 9 1. Background 11 Global forest carbon budget 12 A brief history of REDD+ 13 Brief overview of global REDD+ finance 16 2. REDD+ in India 20 India's position on REDD+ 20 Carbon sequestration in existing forests of India 20 Scope of improvement in the carbon stock of Indian forests 21 India's forest governance framework vis-à-vis REDD+ 23 India's strategy on REDD+ 24 REDD+ initiatives in India 26 Case study: East Khasi Hills REDD+ project, Meghalaya 27 3. -

Unregulated Entry and Exit on the Site;

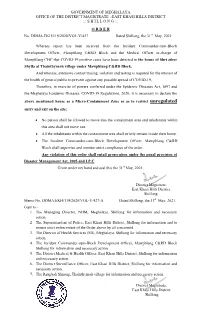

GOVERNMENT OF MEGHALAYA OFFICE OF THE DISTRICT MAGISTRATE ::EAST KHASI HILLS DISTRICT ::: S H I L L O N G ::: O R D E R No. DDMA.EKH/119/2020/VOL-V/427 Dated Shillong, the 31st May, 2021. Whereas report has been received from the Incident Commander-cum-Block Development Officer, Mawphlang C&RD Block and the Medical Officer in-charge of Mawphlang CHC that COVID-19 positive cases have been detected in the house of Shri aibor Shylla at Thainthynroh village under Mawphlang C&RD Block, And whereas, extensive contact tracing, isolation and testing is required for the interest of the health of general public to prevent against any possible spread of COVID-19, Therefore, in exercise of powers conferred under the Epidemic Diseases Act, 1897 and the Meghalaya Epidemic Diseases, COVID-19 Regulations, 2020, it is necessary to declare the above mentioned house as a Micro-Containment Zone so as to restrict unregulated entry and exit on the site; No person shall be allowed to move into the containment area and inhabitants within this area shall not move out. All the inhabitants within the containment area shall strictly remain inside their home. The Incident Commander-cum-Block Development Officer, Mawphlang C&RD Block shall supervise and monitor strict compliance of the order. Any violation of this order shall entail prosecution under the penal provision of Disaster Management Act, 2005 and I.P.C. Given under my hand and seal this the 31st May, 2021. District Magistrate, East Khasi Hills District, Shillong. Memo No. DDMA.EKH/119/2020/VOL-V/427-A Dated Shillong, the 31st May, 2021. -

Details of the Types of Areas Covered Under the IWMP Programme

DETAILED PROJECT REPORT OF WAH UMLYNGDOH AND UMJANI WATERSHED INTEGRATED WATERSHED MANAGEMENT PROJECT – IX- 2010-2011. EAST KHASI HILLS DISTRICT UNDER MAWPHLANG C & RD BLOCK 2010-2011 EAST KHASI HILLS DISTRICT 1 SOIL AND WATER CONSERVATION DEPARTMENT TERRITORIAL DIVISION : SHILLONG 2 3 SUMMARY Name of the Sate : Meghalaya Name of the District : East Khasi Hills District Name of the C&RD Block : Mawphlang C & RD Block Name of the Village : (i) Krang Nonglum (ii) Krang Nongrum(iii) Krang Nongrum Centre (iv) Krang Mawkhar Marbaniang (v) Phudmyrdong (vi) Mawkohtep (vii) Jani Mawiong Name of the Project : East Khasi Hills – IWMP – IX Total Geographical Area : 1456 Ha Total Treatment Area : 1000 Ha Total Project Cost : 150 lakhs Project Duration : 5 Years Project Implementing Agency : Soil & Water Conservation Territorial Division, Shillong. 4 TABLE OF CONTENTS CHAPTER I INTRODUCTION AND BACKGROUND …………………………………………………. 6 CHAPTER II BASIC INFORMATION OF THE PROJECT AREA …………………………………… 11 CHAPTER III PROJECT PLANNING AND INSTITUTION BUILDING…………………………….. 22 CHAPTER IV PROJECT ACTIVITIES …………………………………………………………………. 29 CHAPTER V PROJECT PHASING AND BUDGETING ……………………………………………… 44 CHAPTER VI CAPACITY BUILDING ………………………………………………………………….. 55 CHAPTER VII EXPECTED OUTCOME ………………………………………………………………… 59 ANNEXURE I MAPS ……………………………………………………………………………………….. 76 ANNEXURE II – SOCIO ECONOMIC SURVEY DETAILS …………………………………………… 93 ANNEXURE III – COST ESTIMATES …………………………………………………………………… 124 ANNEXURE IV – CONVERGENCE CERTICIATE FROM DEPUTY COMMISSIONER EAST KHASI -

East Khasi Hills District ::: Shillong

GOVERNMENT OF MEGHALAYA OFFICE OF THE DISTRICT MAGISTRATE ::EAST KHASI HILLS DISTRICT ::: S H I L L O N G ::: O R D E R No. DDMA.EKH/119/2020/VOL-V/286 Dated Shillong, the 19th May, 2021. Whereas report has been received from the Incident Commander-cum-Block Development Officer, Mawphlang C&RD Block and the Medical Officer in-charge of Mawphlang CHC that there has been a rapid increase of COVID-19 positive cases in locality of Mawdumdum (Dongiewrim) under Mawphlang Zone, with a total number of 24 (twenty four) active cases, Therefore, in order to prevent further transmission among the susceptible population, early detection through active house to house (H-T-H) search for persons with symptoms, persons with co-morbidities and contact tracing of the high-risk and low-risk contacts is required, And whereas, for effective house to house (H-T-H) surveillance, complete containment of the area is required to ensure people stay indoors during the active search of cases, Therefore, in the interest of the health of general public to prevent against any possible spread of COVID-19 and in exercise of powers conferred under the Epidemic Diseases Act, 1897 and the Meghalaya Epidemic Diseases, COVID-19 Regulations, 2020, it is deemed necessary to declare the entire locality of Mawdumdum (Dongiewrim) under Mawphlang C&RD Block as a Containment Zone so as to restrict unregulated entry and exit on the site; All the inhabitants within the containment area shall strictly remain inside their homes. No person/public shall be allowed to move into the containment area and inhabitants within the Containment area shall not move out. -

Analysis of Local Attitudes Toward the Sacred Groves of Meghalaya and Karnataka, India

[Downloaded free from http://www.conservationandsociety.org on Tuesday, August 20, 2013, IP: 129.79.203.216] || Click here to download free Android application for this journal Conservation and Society 11(2): 187-197, 2013 Article Analysis of Local Attitudes Toward the Sacred Groves of Meghalaya and Karnataka, India Alison Ormsby Department of Environmental Studies, Eckerd College, St. Petersburg, FL, USA E-mail: [email protected] Abstract The sacred groves of India represent a long-held tradition of community management of forests for cultural reasons. This study used social science research methods in the states of Meghalaya and Karnataka to determine local attitudes toward the sacred groves, elements of sacred grove management including restrictions on resource use, as well as ceremonies associated with sacred groves. Over a seven-month period, 156 interviews were conducted in 17 communities. Residents identified existing taboos on use of natural resources in the sacred groves, consequences of breaking the taboos, and the frequency and types of rituals associated with the sacred groves. Results show that numerous factors contribute to pressures on sacred groves, including cultural change and natural resource demands. In Meghalaya, the frequency of rituals conducted in association with the sacred groves is declining. In both Meghalaya and Karnataka, there is economic pressure to extract resources from sacred groves or to reduce the sacred grove size, particularly for coffee production in Kodagu in Karnataka. Support for traditional ceremonies, existing local community resource management, and comprehensive education programs associated with the sacred groves is recommended. Keywords: sacred grove, community management, sacred forest, traditional conservation practices, sacred natural sites, Meghalaya, Karnataka, India INTRODUCTION these are disappearing due to cultural change and pressure to use the natural resources that they contain (Chandrakanth et Sacred forests, often referred to as sacred groves, are sites al. -

Khasi Hills REDD+ Project

Khasi Hills REDD+ Project Distinctive features The Khasi Hills REDD+ Project is situated in the East Khasi Hills District of Meghalaya, India. The project is to be managed and implemented by indigenous communities with support from Community Forestry International, the Bethany Society, the Khasi Hills Autonomous District Council, Planet Action and the Waterloo Foundation. The project emerged from activities launched by Community Forestry International (CFI) in northeast India in 2003. Meghalaya has been chosen as a pilot project area due to the existence of long established Khasi traditions of forest conservation and legal rights for natural resource management, increased population and economic development pressures, climate change, as well as the unique flora and fauna existing in the region. Rapid deforestation throughout the East Khasi Hills district threatens upland watersheds, household livelihood, while releasing substantial quantities of carbon. Recent loss of forest cover in the Khasi Hills District has been dramatic averaging 5.6% per year from 2000 to 2005. The project seeks to demonstrate how communities and indigenous governance institutions, coordinated though their own federation, can implement REDD+ activities that control drivers of deforestation. The Khasi Hills of Meghalaya is comprised of small tribal administrative units known as Hima. Most of the forests in the project area are under the stewardship of one of 10 Hima and are managed by Hima Dorbar, an indigenous council represented by all male adults of every constituent village. The 10 Hima span approximately 62 villages and small hamlets. CFI supported the 10 Hima in the project area to form a federation to manage the project. -

Khasi Hills Community REDD+ Project: Restoring and Conserving Meghalaya’S Hill Forests Through Community Action

Khasi Hills Community REDD+ Project: Restoring and Conserving Meghalaya’s Hill Forests through Community Action Project Design Document Submitted to Plan Vivo, UK by Community Forestry International on behalf of Ka Synjuk Ki Hima Arliang Wah Umiam, Mawphlang Welfare Society Mawphlang, Meghalaya, North Eastern India VERSION 3.0 3 APRIL 2017 1 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY The Khasi Hills REDD+ Project is situated in the East Khasi Hills District of Meghalaya, India. The project covers 27,139 hectares, comprised of approximately 9,270 hectares of dense forests and 5,947 hectares of open forests in 2010. The project engages ten indigenous Khasi governments (hima) with approximately 62 villages and small hamlets. Meghalaya has been chosen as a pilot project area due to the existence of long established Khasi traditions of forest conservation and legal rights for natural resource management, increased population and economic development pressures, climate change, as well as the unique flora and fauna existing in the region. In 2017, the project contracted its first five-year verification (2011-2016) to determine impacts and as a result, the technical specifications and Project Design Document were updated to reflect actual impacts on avoided deforestation (REDD+) and Assisted Natural Regeneration (ANR). Data on forest cover changes is presented in this revised Project Design Document and the revised Technical Specifications. Rapid deforestation throughout the East Khasi Hills district threatens upland watersheds, household livelihoods, while releasing substantial quantities of carbon. Loss of forest cover in the Khasi Hills District has been dramatic, averaging 5.6% per year from 2000 to 2005. Over the next 30 years this REDD+ project is designed to slow, halt and reverse the loss of community forests by providing institutional support, new technologies for forest management, and financial incentives to conserve existing old growth community forests while regenerating degraded forests.