Jl-I 3G a CONTENT ANALYSIS of CHILDREN's

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

ALISE 2011 Annual Conference

Preliminary Conference at a Glance (as of January 7, 2014) Tuesday, January 21, 2014 Time Event 8:00 a.m. - 6:00 p.m. Registration 8:00 a.m. - 6:00 p.m. Internet Cafe 8:00 a.m. - 8:00 p.m. Placement Services 10:00 a.m. – Noon WISE Pedagogy Pre-conference Workshop: Designing Online Courses for Diverse Communities of Learners Moderator: Nicole A. Cooke, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign Presenters: Lilia Pavlovsky, Rutgers University; Michael Stephens, San Jose State University; and Jill Hurst-Wahl, Syracuse University 12:30 p.m. - 4:30 p.m. ALISE Academy: MOOCs, Venture Creation and Education: Educational Entrepreneurship and the LIS Educator Sponsored by The H. W. Wilson Foundation 1. “MOOCs in Modern Online Education” Workshop Leader: Karl Okamoto, Drexel University 2. “The Promise of Educational Entrepreneurship for LIS Education” VIRTUAL CONFERENCE Workshop Leaders: Mike D’Eredita, John Liddy, and Marcie Sonneborn, Syracuse University 1:00 p.m. - 4:00 p.m. Curriculum Vitae and Portfolio Review 1:00 p.m. - 4:00 p.m. ALISE Board of Directors Meeting 4:30 p.m. - 5:30 p.m. ALISE Leadership Orientation 5:00 p.m. - 5:30 p.m. Set-up for Works in Progress Poster Session 5:30 p.m. -6:30 p.m. ALISE Committee Meetings 5:30 p.m. – 6:30 p.m. 2014 and 2015 ALISE Program Planning Committees Joint Meeting 6:30 p.m. – 9:00 p.m. Opening Reception/Works In Progress Poster Session VIRTUAL CONFERENCE (Hors d’oeuvres and Cash Bar) Wednesday, January 22, 2014 NOTE: Presentations designated as “Featured Presentation” were selected based on reviewers’ scores and comments. -

Guide to the Zena Bailey Sutherland Papers 1953-2003

University of Chicago Library Guide to the Zena Bailey Sutherland Papers 1953-2003 © 2007 University of Chicago Library Table of Contents Acknowledgments 3 Descriptive Summary 3 Information on Use 3 Access 3 Citation 3 Biographical Note 3 Scope Note 4 Related Resources 5 Subject Headings 6 INVENTORY 6 Series I: Biographical Materials 6 Series II: Graduate Library School 7 Series III: General Files 7 Series IV: Correspondence 11 Series V: Writings, Speeches and Publications 25 Subseries 1: Books 25 Subseries 2: Articles 28 Subseries 3: Presentations 31 Subseries 4: Correspondence with Publishers 32 Series VI: Subject and Clipping Files 33 Series VII: Audio-Visual Materials 37 Series VIII: Restricted Materials 38 Descriptive Summary Identifier ICU.SPCL.SUTHERLAND Title Sutherland, Zena Bailey. Papers Date 1953-2003 Size 16 linear feet (32 boxes) Repository Special Collections Research Center University of Chicago Library 1100 East 57th Street Chicago, Illinois 60637 U.S.A. Abstract Zena Bailey Sutherland (1915-2002) (AB 1937, AM 1958 University of Chicago) was associated with the University of Chicago Graduate Library School throughout her career as faculty and as editor and reviewer for the Bulletin of the Center for Children's Books from 1958 to 1985. Over the course of her career, she reviewed more than 30,000 children’s books, for the Bulletin and as children’s book editor for the Saturday Review and the Chicago Tribune. She authored six editions of the classic text Children and Books The Sutherland Papers consist of materials from work in the Graduate Library School, papers regarding her service on the Newbery, Caldecott, and other children’s literature award committees, speeches and writings, biographical materials, and correspondence related to her professional work at the University and as editor and author for children’s literature. -

Annotated Bibliography: Storytelling

IS 245 Information Access / Maack MELISSA ELLIOTT Annotated Bibliography Page 1 of 5 ANNOTATED BIBLIOGRAPHY Storytelling has a rich heritage in every culture and every era. It is, or should be, a part of the training of children’s librarians for both public and school libraries; this bibliography of resources, consisting of “how to find material” (which oftentimes includes some of the material itself), and also “how to do it” should prove useful for librarians, teachers, and possibly dedicated parents interested in expanding their ability to “tell me a story.” Books These books were culled from bibliographic sections at the end of each chapter of The Storyteller’s Start-up Book, by Margaret Read MacDonald, and also from a search for “storytell?” on Librarians Index to the Internet (http://LII.org) and on the LAPL website. 1. MacDonald, Margaret Read. The Storyteller’s Sourcebook: A Subject, Title, and Motif-Index to Folklore Collections for Children. Detroit: Neal-Schuman / Gale Research, 1982. This massive work indexes 556 folktale collections and 389 picture books, which encompass all folktale titles in Children’s Catalog 1961-1981 plus all folktale titles mentioned in Booklist reviews 1960-1980. It is the first reference tool to bring together from children’s collections variants of each folktale and to supply descrip- tions of them. It is broken down into four indexes: Motif, Tale Title, Subject, and Ethnic/Geographic. The Motif Index makes use of Finnish folklorist Antti Aarne’s 1910 numbering system according to Type and Motif. The tales are also categorized in sub-topics: for instance, Cinderella + glass slipper + cruel stepmother, etc., which follows 1932 Indiana University folklorist Stith Thompson’s classifications (though not in such minute detail). -

2018 May Hill Arbuthnot Lecture

Children the journal of the Association for Library Service to Children Libraries● June 2018 ISSN 1542-9806 & Digital Supplement 2018 May Hill Arbuthnot Honor Lecture Naomi Shihab Nye Refreshments Will Be Served: Our Lives of Reading & Writing Table Contents of Digital Supplement ● June 2018 Editor Sharon Verbeten, De Pere, Wisconsin Editorial Advisory Committee Randall Enos, Chair, Middletown, New York Anna Haase Krueger, St. Paul, Minnesota 2 Introduction Jeremiah Henderson, Renton, Washington Lettycia Terrones, Urbana, Illinois Lisa Von Drasek, St. Paul, Minnesota Virginia A. Walter, Los Angeles, California 3 Lecture Nina Lindsay, ALSC President, Ex Officio, Oakland, California Refreshments Will Be Served: Sharon Verbeten, Editor, Ex Officio, De Pere, Wisconsin Executive Director Our Lives of Reading & Writing Aimee Strittmatter Managing Editor 12 Arbuthnot Luncheon: Feast for the Mind Laura Schulte-Cooper Website and Soul www.ala.org/alsc Circulation Children and Libraries (ISSN 1542-9806) is a refereed journal published four times per year by 12 About May Hill Arbuthnot the American Library Association (ALA), 50 E. Huron St., Chicago, IL 60611. It is the official pub- lication of the Association for Library Service to Children (ALSC), a division of ALA. Subscription price: members of ALSC, $20 per year, included in membership dues; nonmembers, $50 per year in the U.S.; $60 in Canada, Mexico, and other countries. Back issues within one year of current Cover photo credit: Rajah Bose, Gonzaga University. issue, $15 each. POSTMASTER: Send address changes to Children and Libraries, 50 E. Huron St., Chicago, IL 60611. Members send mailing labels or facsimile to Member Services, 50 E. -

2010 May Hill Arbuthnot Honor Lecture Had Performed Some Such Heroic Deed

t is a great honor to be standing here all his work within ALSC on behalf of before you to deliver the 2010 May Hill children’s librarians, children, and books. IArbuthnot Lecture. When Arbuthnot Chair Kristi Jemtegaard first called me As soon as I got the news that Riverside way back in August of 2008 to give me County Library System had been selected the news, her first words after identifying as the host site, I contacted Mark to 2010 herself were, “I bet you can guess why I’m find out why, exactly, they had applied calling.” to host a lecture that I would write and May Hill deliver. He told me that it was due to my Actually, I couldn’t. The only thing I could work in multicultural literature, since the think of was that it had something to do community here is a diverse one, and Arbuthnot with the 2009 Arbuthnot Lecture, hosted they, too, are passionate about books that by the Langston Hughes Library at the reflect that diversity. I was very happy Honor Alex Haley Farm in Clinton, Tennessee, to hear this from Mark because—if you because I had written a letter of sup- don’t know it by now you will within the port for Theresa Venable and her wonder- hour—multicultural literature is my pas- Lecture ful committee who had submitted what sion, and I love to talk about it. turned out to be the winning applica- Can Children’s Books tion. I actually thought that Kristi might I told Mark that I was thinking of using have a question about the feasibility of a the title “Why Multicultural Literature Save the World? shuttle bus from the Knoxville Airport to Matters.” There was a little silence on the farm. -

Margaret K. Mcelderry and the Professional Matriarchy of Children’S Books

Margaret K. McElderry and the Professional Matriarchy of Children’s Books BETSYHEARNE ABSTRACT AMATRIARCHYISDEFINED AS “a form of social organization in which the mother is recognized as the head of the family or tribe, descent and kinship be- ing traced through the mother; government, rule, or domination by women” ( Websterk New World Dictionary, 1995). Focusing on renowned editor Margaret K. McElderry, this article develops the idea of children’s book publishing as a field dominated by strong, often subversive, matri- archal leaders who have advanced the status, and enhanced the quality, of juvenile literature through an intricate female kinship structure. The birth and development of a relatively new genre has required binding ties in the face of a powerful patriarchal business society that viewed children’s literature as unimportant and unworthy of major investment or recognition. The values, codes, and consolidation of the profession are passed on in stories that serve the function of, and bear many resem- blances to, family narrative. Quotes without citations are taken from two interviews, the first with Susan Cooper on May 5, 1995, and the second with Margaret K. McElderry on June 22, 1995. INTRODUCTION In both the oral and printed traditions of western culture, women have been the principal storytellers during children’s early stages of de- velopment and often during their later stages as well. Although men have achieved classic status as collectors of stories in the oral tradition, a close look at the work of pioneers such as the Grimm brothers and An- drew Lang reveals how much each relied on female sources-the Grimm Betsy Hearne, Graduate School of Library and Information Science, 501 E. -

A Message from Your YSS President 2013: Jennifer Ogrodowski, President Autumn Is My Favorite Season

Issue 4 Fall 2013 YSS Board A Message From Your YSS President 2013: Jennifer Ogrodowski, President Autumn is my favorite season. I love the idea of a new beginning with both a school [email protected] year and the regular routines of the library. The summer reading program has ended, Joyce Laiosa, Past-President the reports are almost done, and the statistics for the NYS Library have been [email protected] compiled. Some may think of this as the end of the summer, but I’m more inclined Chrissie Morrison, 1st VPres. towards a renewal and opportunity to evaluate my job performance. I have goals, [email protected] from cleaning off the top of my desk to incorporating more early literacy skills into Christina Ryan-Linder, 2nd VPres storytimes, booklists, and new signage around the children’s area. [email protected] Deborah Hempe, 1st Year Director Then reality sinks in and I realize I don’t have time to be creative; under that pile on [email protected] my desk is an old list of goals and chores – which looks so similar it could have been written 10 years ago, or yesterday. Before I become disappointed, I toss them all Terry Rabideau, 2nd Year Direc- tor [email protected] away and start again, with something new. New ideas, new challenges come from opportunities where I meet friends and colleagues, such as NYLA Conference in Cathy Henderson, 3rd Year Direc- tor [email protected] Niagara Falls. “Libraries Spark Imagination” is this year’s theme; a perfect response to my dilemma. -

A Permanent and Significant Contribution the Life of May Hill Arbuthnot

PEER-REVIEWED A Permanent and Significant Contribution The Life of May Hill Arbuthnot SHARON MCQUEEN May Hill Arbuthnot ay Hill Arbuthnot (1884–1969) was not a children’s Early Influences and Career librarian, nor did she teach children’s librarianship. M She was not a scholar of children’s librarianship. Born in Mason City, Iowa, where her parents were visit- How, then, did she come to have an entry in the biographical ing friends, Arbuthnot spent her happy, early years in dictionary Pioneers and Leaders in Library Services to Youth Massachusetts, Minnesota, and Chicago, where she graduated among the pantheon of youth services legends that included from Hyde Park High School.4 Her mother nurtured a love of Anne Carroll Moore, Augusta Baker, Mildred Batchelder, and music, poetry, and books, and as Arbuthnot recalled, “provided Charlemae Rollins?1 Why did American Libraries include her us with the Alcott books and swung us into Dickens and the among one hundred of the most important leaders of librari- Waverley novels at an early age.”5 Arbuthnot and her brother anship in the twentieth century?2 And why did ALA’s Children’s were read to by a father with a fine voice who enjoyed read- Services Division (now ALSC) agree to administer a lecture ing aloud. As Arbuthnot approached her eightieth year, she series named in Arbuthnot’s honor?3 looked back on her father’s readings and rereadings of Robinson Sharon McQueen is an Assistant Professor in the Library Science Program of Old Dominion University. in Norfolk, Va. Her research has received multiple awards from the Association for Library and Information Science Education (ALISE) and the American Library Association (ALA), including the Phyllis Dain Library History Dissertation Award and the Library Research Round Table Jesse H. -

KERLAN COLLECTION Children’S Literature Research Collections

THE KERLAN COLLECTION Children’s Literature Research Collections FALL 2015 NEWSLETTER | CO-SPONSORED BY THE KERLAN FRIENDS AND THE CLRC Kerlan Friends President Update Greetings on Behalf of the Kerlan Friends Board! I’m not sure where the summer has gone. Perhaps the winds that come with late summer storms have blown the time away. The leaves at the top of the signal tree in the yard across the street from my house have been touched by gold, which means that autumn and the start of classes are not far away. One of the highlights of the summer was the special program featuring the conversation illustrator Ariane Dewey, editor Ava Weiss, and Caldecott Award winning illustrator Paul Zelinsky had about the production of color illustrations— particularly color separations—on June 10. They used materials Ariane Dewey had (Above) Caldecott-winning recently donated to the Kerlan Collection. illustrator Paul Zelinsky and The program, along with additional donor Ariane Dewey discuss conversations about the creation of the history of the children’s children’s books that were fi lmed during book printing process with a lithography stone from the illustrators’ and editor’s visit, should the Ingri and Parin D’Aulaire be available online in 2016. Collection Kerlan Friends President Update (Right) Paul Zelinsky, Ava cont. on page 2 Weiss, and Ariane Dewey presenting on color separations The University of Minnesota is an equal opportunity educator and employer. To receive this information in alternative formats, or for disability accommocations, contact CLRC at [email protected] or 612-624-4576. Contents Kerlan Friends President Update cont. -

2018 May Hill Arbuthnot Lecture

Arbuthnot Luncheon: Feast for the Mind and Soul A special luncheon, celebrating young people and expression, Contest, which encourages young was held on April 28, prior to the Arbuthnot Honor Lecture. writers to explore through poetry The event showcased the literary and dramatic talents of themes like apologizing, listening, Whatcom County youth in presentations that often touched building peace, and anti-bullying. A on themes of peace and finding common ground, which Forest of Words is a print collection perfectly underscored and complemented the work of Naomi of original poetry by young people Shihab Nye, 2018 Arbuthnot lecturer. in grades six through twelve, pub- lished by Teen Services of Whatcom A one-act play was performed by BAAY: Bellingham Arts County Library System and distrib- Academy for Youth. “Us & Them,” written by David Campton uted to area schools and libraries. and directed by Ian Bivins, portrayed the story of two neigh- boring groups who arrive in the same space and proceed to “The voices of the young people build a wall to keep their communities separate. The drama, speaking truth were a profound performed by 13 to 18-year-olds, brought into focus what tonic to all present,” said Nye. “The unites people and what keeps them apart. play was eerily prescient in light of our current moment—walls and breaking up of immigrant families and racism and all The lunch and program would not have been complete with- the sorrows abounding. I felt as if the luncheon cleansed and out poetry, of course, and there was plenty to be enjoyed. -

May Hill Arbuthnot Honor Lecture That If I Were Taller I Could Somehow Bet- Was Presented May 3, 2014, at the Ter Rise to This Occasion

The May Hill Arbuthnot Honor Lecture that if I were taller I could somehow bet- was presented May 3, 2014, at the ter rise to this occasion. But I see now May Hill University of Minnesota Children’s that I could have left my heels back in Literature Research Collections on the Brooklyn, New York, where I live. Arbuthnot university’s West Bank Campus. When I look out at all of you, I realize Good evening, beautiful people! that I don’t need big shoes to get a boost. Honor So many of you folks who work with I am so happy to be here. Thank you, children and literature understand what Lecture May Hill Arbuthnot Honor Committee. it’s like when a person feels small and Thank you to our National Ambassador needs a lift. You understand this because for Young People’s Literature and this as believers in the power of reading and Rejoice the Legacy! year’s Newbery medal recipient, the kids, you have what it takes to make a amazing Kate DiCamillo. And a very person feel a million feet tall. The very Andrea Davis Pinkney special thanks to Lisa Von Drasek, essence of that idea lifts me up very high. curator of the Children’s Literature Research Collections of the University of * * * * Minnesota Libraries, and her colleagues at Archives and Special Collections at I’d like to start with a story. the University of Minnesota. You have worked hard wrangling the many facets Once, a very long time of this event. This evening would not be ago, there was a girl. -

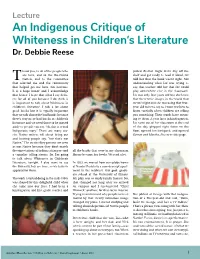

2018 May Hill Arbuthnot Lecture

Lecture An Indigenous Critique of Whiteness in Children’s Literature Dr. Debbie Reese hank you, to all of the people who pulled Brother Eagle Sister Sky off the are here, and to the Ho-Chunk shelf and got ready to read it aloud, Liz T Nation, and to the committee told her that the book wasn’t right. Not that selected me and the community understanding what Liz was trying to that helped get me here. I’m nervous. say, that teacher told her that she could It is a huge honor and I acknowledge play somewhere else in the classroom. that honor. I hope that what I say deliv- Liz was only four years old but she knew ers for all of you because I do think it that there were images in the world that is important to talk about Whiteness in weren’t right and she was using that four- children’s literature. I talk a lot about year-old voice to say so. I want teachers to good books but it is equally important listen carefully when children are telling that we talk about the bad books because you something. Their words have mean- there’s way more bad books in children’s ing to them. A year later in kindergarten, literature and we need those to be moved Liz came out of her classroom at the end aside so people can say, “oh, this is actual of the day, plopped right down on the Indigenous story.” There are many sto- floor, opened her backpack, and opened ries Native writers tell about being out George and Martha, Encore to this page.