Variable Plumage Coloration of Breeding Barbary Falcons Falco

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Observation of Shaheen Falcon Falco Peregrinus Peregrinator (Aves: Falconiformes: Falconidae) in the Nilgiris, Tamil Nadu, India

OPEN ACCESS The Journal of Threatened Taxa fs dedfcated to bufldfng evfdence for conservafon globally by publfshfng peer-revfewed arfcles onlfne every month at a reasonably rapfd rate at www.threatenedtaxa.org . All arfcles publfshed fn JoTT are regfstered under Creafve Commons Atrfbufon 4.0 Internafonal Lfcense unless otherwfse menfoned. JoTT allows unrestrfcted use of arfcles fn any medfum, reproducfon, and dfstrfbufon by provfdfng adequate credft to the authors and the source of publfcafon. Journal of Threatened Taxa Bufldfng evfdence for conservafon globally www.threatenedtaxa.org ISSN 0974-7907 (Onlfne) | ISSN 0974-7893 (Prfnt) Note Observatfon of Shaheen Falcon Falco peregrfnus peregrfnator (Aves: Falconfformes: Falconfdae) fn the Nflgfrfs, Tamfl Nadu, Indfa Arockfanathan Samson, Balasundaram Ramakrfshnan, Palanfsamy Santhoshkumar & Sfvaraj Karthfck 26 October 2017 | Vol. 9| No. 10 | Pp. 10850–10852 10.11609/jot. 3040 .9. 10. 10850–10852 For Focus, Scope, Afms, Polfcfes and Gufdelfnes vfsft htp://threatenedtaxa.org/About_JoTT For Arfcle Submfssfon Gufdelfnes vfsft htp://threatenedtaxa.org/Submfssfon_Gufdelfnes For Polfcfes agafnst Scfenffc Mfsconduct vfsft htp://threatenedtaxa.org/JoTT_Polfcy_agafnst_Scfenffc_Mfsconduct For reprfnts contact <[email protected]> Publfsher/Host Partner Threatened Taxa Journal of Threatened Taxa | www.threatenedtaxa.org | 26 October 2017 | 9(10): 10850–10852 Note The Shaheen Falcon Falco Observation of Shaheen Falcon peregrinus peregrinator is a Falco peregrinus peregrinator subspecies of the -

Falconry Threatens Barbary Falcons in The

Falconry Threatens Barbary Falcons in the Canary Islands Through Genetic Admixture and Illegal Harvest of Nestlings Authors: Beneharo Rodríguez, Felipe Siverio, Manuel Siverio, and Airam Rodríguez Source: Journal of Raptor Research, 53(2) : 189-197 Published By: Raptor Research Foundation URL: https://doi.org/10.3356/JRR-17-96 BioOne Complete (complete.BioOne.org) is a full-text database of 200 subscribed and open-access titles in the biological, ecological, and environmental sciences published by nonprofit societies, associations, museums, institutions, and presses. Your use of this PDF, the BioOne Complete website, and all posted and associated content indicates your acceptance of BioOne’s Terms of Use, available at www.bioone.org/terms-of-use. Usage of BioOne Complete content is strictly limited to personal, educational, and non-commercial use. Commercial inquiries or rights and permissions requests should be directed to the individual publisher as copyright holder. BioOne sees sustainable scholarly publishing as an inherently collaborative enterprise connecting authors, nonprofit publishers, academic institutions, research libraries, and research funders in the common goal of maximizing access to critical research. Downloaded From: https://bioone.org/journals/Journal-of-Raptor-Research on 04 Sep 2019 Terms of Use: https://bioone.org/terms-of-use Access provided by CSIC SHORT COMMUNICATIONS J. Raptor Res. 53(2):189–197 Ó 2019 The Raptor Research Foundation, Inc. FALCONRY THREATENS BARBARY FALCONS IN THE CANARY ISLANDS THROUGH GENETIC ADMIXTURE AND ILLEGAL HARVEST OF NESTLINGS 1 BENEHARO RODRIGUEZ´ , FELIPE SIVERIO, AND MANUEL SIVERIO Canary Islands’ Ornithology and Natural History Group (GOHNIC), La Malecita s/n, 38480 Buenavista del Norte, Tenerife, Canary Islands, Spain AIRAM RODRIGUEZ´ Department of Evolutionary Ecology, Estacio´n Biolo´gica de Donana˜ (CSIC), Avda. -

AERC Wplist July 2015

AERC Western Palearctic list, July 2015 About the list: 1) The limits of the Western Palearctic region follow for convenience the limits defined in the “Birds of the Western Palearctic” (BWP) series (Oxford University Press). 2) The AERC WP list follows the systematics of Voous (1973; 1977a; 1977b) modified by the changes listed in the AERC TAC systematic recommendations published online on the AERC web site. For species not in Voous (a few introduced or accidental species) the default systematics is the IOC world bird list. 3) Only species either admitted into an "official" national list (for countries with a national avifaunistic commission or national rarities committee) or whose occurrence in the WP has been published in detail (description or photo and circumstances allowing review of the evidence, usually in a journal) have been admitted on the list. Category D species have not been admitted. 4) The information in the "remarks" column is by no mean exhaustive. It is aimed at providing some supporting information for the species whose status on the WP list is less well known than average. This is obviously a subjective criterion. Citation: Crochet P.-A., Joynt G. (2015). AERC list of Western Palearctic birds. July 2015 version. Available at http://www.aerc.eu/tac.html Families Voous sequence 2015 INTERNATIONAL ENGLISH NAME SCIENTIFIC NAME remarks changes since last edition ORDER STRUTHIONIFORMES OSTRICHES Family Struthionidae Ostrich Struthio camelus ORDER ANSERIFORMES DUCKS, GEESE, SWANS Family Anatidae Fulvous Whistling Duck Dendrocygna bicolor cat. A/D in Morocco (flock of 11-12 suggesting natural vagrancy, hence accepted here) Lesser Whistling Duck Dendrocygna javanica cat. -

Current Status of Falcon Populations in Saudi Arabia Albara M

South Dakota State University Open PRAIRIE: Open Public Research Access Institutional Repository and Information Exchange Theses and Dissertations 2016 Current Status of Falcon Populations in Saudi Arabia Albara M. Binothman South Dakota State University Follow this and additional works at: http://openprairie.sdstate.edu/etd Part of the Natural Resources and Conservation Commons, and the Ornithology Commons Recommended Citation Binothman, Albara M., "Current Status of Falcon Populations in Saudi Arabia" (2016). Theses and Dissertations. 976. http://openprairie.sdstate.edu/etd/976 This Thesis - Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by Open PRAIRIE: Open Public Research Access Institutional Repository and Information Exchange. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Open PRAIRIE: Open Public Research Access Institutional Repository and Information Exchange. For more information, please contact [email protected]. CURRENT STATUS OF FALCON POPULATIONS IN SAUDI ARABIA BY ALBARA M. BINOTHMAN A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Master of Science Major in Wildlife and Fisheries Sciences South Dakota State University 2016 ii CURRENT STATUS OF FALCON POPULATIONS IN SAUDI ARABIA This thesis is approved as a creditable and independent investigation by a candidate for the Master of Science in Wildlife and Fisheries Sciences degree and is acceptable for meeting the thesis requirements for this degree. Acceptance of this does not imply that the conclusions reached by the candidate are necessarily the conclusions of the major department. _______________________________________ Troy W. Grovenburg, Ph.D Date Thesis Advisor _______________________________________ Michele R. Dudash. Ph.D. Date Head. -

Red Necked Falcon

Ca Identifi cation Habit: The Red-necked Falcon is an arboreal and Features: Cultural Aspects: aerial crepuscular bird. Lives and hunts in pairs. In ancient India this falcon was Flight is fast and straight. It is capable of hovering. esteemed by falconers as it hunts in 1st and 4th primary pairs, is easily trained and is obedient. Distributation: India upto Himalayan foothills and subequal. 2nd and 3rd It took birds as large as partridges. terrai; Nepal, Pakistan and BanglaDesh. South of primary subequal. In ancient Egypt, Horus, was the Sahara in Africa. Crown and cheek stripe falcon-headed god of sun, war and chestnut. protection and was associated with Habitat: Keeps to plain country with deciduous the Pharoahs. vegetation, hilly terrain, agricultural cropland with Bill plumbeous, dark groves, semiarid open scrub country and villages. tipped. Avoids forests. Iris brown. Related Falcons: Behaviour: Resident falcon with seasonal Cere, orbital skin, legs and Common Kestrel, Shaheen and Laggar Falcon are residents . The movements that are not studied. Swiftly chases feet yellow. Peregrine, Eurasian Hobby and Merlin are migrants. Red-legged crows, kites and other raptors that venture near its Falcon is extra-limital and is not recorded from India. nest. Shrill call is uttered during such frantic chase. Utters shrill and piercing screams ki ki ki ki, with diff erent calls, grates and trills for other occasions. Female feeds the male during the breeding season. A pair at sunrise roosting on the topmost perches of a tall tree Claws black. Tail broad with black sub-terminal band. Thinly barred abdomen MerlinM Common Kestrel Laggar Falcon Amur Falcon and fl anks. -

Bird-O-Soar Observation of Shaheen Falcon in Odisha, India

#54 Bird-o-soar 21 September 2020 Observation of Shaheen Falcon in Odisha, India Shaheen Falcon Falco peregrinus peregrinator is a subspecies of Peregrine Falcon Falco peregrinus found mainly in the Indian subcontinent, Sri Lanka (Dottlinger 2002; Dottlinger & Nicholls 2005), central, southeastern China, and northern Myanmar (de Silva et al. 2007). The Shaheen Falcon has also been reported in Andaman & Nicobar Islands (Pande et al. 2009). It is said to be a resident bird of this region (Ali & Reply 1987) and described as a migratory subspecies by (Molard et al. 2007). According to the few specific data, the Black Shaheen / Shaeen Falcon is apparently rare, only prefer rocky outcrops to forest areas. Breeding pairs are mostly found in Sri Lanka (Wait 1931; Henry 1971; Cade 1982; Brown & A madon 1989; Weick 1989; Lamsfuss 1998; Döttlinger 2002). The national Red Shaheen Falcon Falco List of Sri Lanka peregrinus peregrinator sighted in Takatpur, (https://www.nationalredlist.org/ Baripada Forest Division search2/species-search/) 22.x.2016. classified the subspecies as ‘Vulnerable’ (Hoffmann 1998). The Vulnerable status is concordant with a population estimated to number 63–82 breeding pairs (Döttlinger & Hoffmann 1999; Döttlinger 2002). It is assumed that the population of this subspecies has always been numerically small. At 09.18h on 22 October 2016, we observed the Shaheen Falcon, which flew in front of us and sat on a mobile tower at Baripada, the district of Mayurbhanj, Odisha, which was outside of our university campus (21.909440 N, 86.769110 E). Nearly after a year, on 1 Nov 2017 we spotted this raptor for the second time in Joranda waterfall, Similipal Tiger Reserve, Odisha. -

The Raptor Literature in Eastemasia Concems (8

kr- l1 TheRaptor Literature Lr,ovo F. Krrr relevant raptor literatrye, rather than providing a thor- The Peregrine Fund, oughhistorical review. We focuson regionsmost famil- 5668 W. Flying Hawk Lane, Boise, ID 83709 U.S'A. iar to us, and have touchedlightly on the raptor litera- ture of someparts of the world. Ron G Blr.srrll Raptor researcherssuffer from two chronic prob- Doldersummerweg 1,7983 LD Wapse,The Netherlands lems: too little information and too much information. Traditionally,most researchers, regardless of their dis- Lucrl LIU Snvrnrrcruus cipline,have suffered from a lackof accessto thewhole Research Center for Biodiversity, spectrumof global literature. Few libraries offer com- Academia Sinica, Taipei, Taiwan 115 prehensivecoverage ofall typesofraptor literature,and even now, the major online abstracting services, Jnvcnxr Snnnclltx althoughextremely valuable, do not yet provideaccess Falconry Heritage Trust, to the full text of most articles.Language differences P.O. Box 19, Carmarthen,Dyfed SA335YL, U.K. also have posedperennial barriers to communication, and few, if any, abstractingservices adequately cover the literaturein all of the world'smajor languages. Now, with a flood of information on its way onto INTRODUCTION the worldwide web, we run thb risk of descendingfrom the InformationAge into a stateof information chaos. We are currently experiencinga dramatic change in As a result,raptor literatureis becomingincreasingly scholarlydisciplines, as we shift from traditionalprint vast and amorphous.In his chapteron this topic in the publicationsto electronic forms of communication. first editionof this manual,LeFranc (1987) stated that Duringthis transition,many venerable joumals are pro- approximately370 and 1,030 raptor-relaledpublica- ducingparallel electronic versions and others are com- tionswere listed in the 1970and 1980issues of Wildlife pletely discontinuingtheir print versions. -

Bonner Zoologische Beiträge

© Biodiversity Heritage Library, http://www.biodiversitylibrary.org/; www.zoologicalbulletin.de; www.biologiezentrum.at Bonn. zool. Beitr. Bd. 42 H. 1 S. 27—34 Bonn, März 1991 A preliminary census and notes on the distribution of the Barbary Falcon {Falco pelegrinoides Temminck, 1829) in the Canary Islands Efrain Hernández, Guillermo Delgado, José Carrillo, Manuel Nogales & Vicente Quilis Abstract. As a result of an initial census of the Barbary Falcon in the Canary Islands that was carried out between 1987 and 1988, a total of seven pairs have been detected on the islands of Lanzarote and Fuerteventura. On the other hand, the species can be con- sidered to have become extinct on Tenerife and Gran Canaria. Finally some breeding data are presented and the most important threat factors are analyzed. Key words. Aves, Falconidae, Falco pelegrinoides, census, Canary Islands. Introduction The distribution range of the Barbary Falcon extends over subdesertic areas from the Canary Islands, the interior of Morocco, Tunisia, Algeria, Egypt and Israel to Afghanistan and the Gobi Desert in Asia. For some authors the Barbary Falcon is simply a subspecies of the cosmopolitan Peregrine (Brosset 1986; Weick 1989) though in general, the majority assign it its own specific rank (Voous 1960; Vaurie 1965; Cramp & Simmons 1980; Cade 1982). The criterion for segregation at the species level is based on the biometric and plumage differences together with the fact that the distribution area of both species overlaps in various localities with no hybrids having been detected. However, this argument cannot be regarded as being totally conclusive since a previously undes- cribed intermediate form, apparently restricted to the Atlantic coast of Morocco, has recently been detected (Brosset 1986). -

Trapping Methods Used for the Migratory Falcons in Pakistan

The Pakistan Journal of Forestry Vol.56(1), 2006 TRAPPING METHODS USED FOR THE MIGRATORY FALCONS IN PAKISTAN Mian Muhammad Shafiq1 and Muhammad Idrees2 Abstract Falcons belong to family Falconidae. These are migratory birds. Many species of falcons visit Pakistan i.e. Saker Falcon (Falco charrug) Peregrine Falcon (Falco peregrinus) etc. The survey of migratory falcons was conducted in D.I.Khan, Mardan, Swabi and Nowshera districts of NWFP. It has been observed that Bala Aba Shaheed, Oubha, Kheshki Maira, Aman Garh, Marathi Maira, Naranji Maira, etc are the hot spots of hunting/trapping of migratory falcons in NWFP. During the survey it has been observed that Khudhu, Paidam, Trangri, Dogazza and Patti methods are used for the live catching/trapping of migratory falcons in these areas. The Government of Pakistan has signed International Conventions like CITES, CMS etc. According to the CITES convention Appendices list (www.cites.org) the peregrine falcon is placed in the list of in Appendix l and Saker falcon is in the Appendix II. Whereas both these species are included in the list of Appendix II of the CMS. Introduction Raptors or Birds of Prey belong to a group of large birds that hunt during the daytime rather than night. These include hawks, kites, buzzards, falcons, eagles and certain vultures. Eagles are the largest of this family. The raptors are flesh eating and most of them preferring to kill their own prey. Some of them, which include vultures, feed upon the carcasses of dead animals (Perry, 1990). The most famous among the raptors are the members of Falconidae family of the order Falconiformes. -

The Status of Diurnal Birds of Prey in Turkey

j. RaptorRes. 39(1):36-54 ¸ 2005 The Raptor ResearchFoundation, Inc. THE STATUS OF DIURNAL BIRDS OF PREY IN TURKEY LEVENT TURAN 1 HacettepeUniversity, Faculty of Education, Department of BiologyEducation, 06532 Beytepe,Ankara, Turkey ABSTRACT.--Here,I summarize the current statusof diurnal birds of prey in Turkey This review was basedon field surveysconducted in 2001 and 2002, and a literature review.I completed661 field surveys in different regionsof Turkey in 2001 and 2002. I recorded37 speciesof diurnal raptors,among the 40 speciesknown in the country In addition, someadverse factors such as habitat loss, poisoning, killing, capturingor disturbingraptors, and damagingtheir eggswere seen during observations. KEYWORDS: EasternEurope,, population status; threats;, Turkey. ESTATUSDE LASAVES DE PRESADIURNAS EN TURQUiA RESUMEN.--Aquiresumo el estatusactual de las avesde presa diurnas en Turquia. Esta revisi6nest2 basadaen muestreosde campo conducidosen 2001 y 2002, yen una revisi6nde la literatura. Complet• 661 muestreosde campo en diferentesregiones de Turquia en 2001 y 2002. Registr• 37 especiesde rapacesdiurnas del total de 40 especiesconocidas para el pals. Ademfis,registra algunos factores ad- versoscomo p•rdida de hfibitat, envenenamiento,matanzas, captura o disturbiode rapacesy dafio de sus huevos durante las observaciones. [Traducci6n del equipo editorial] Turkey, with approximately454 bird species,has servations of diurnal raptors collected during a relatively rich avian diversity in Europe. Despite 2001-02 from locationsthroughout Turkey. recognized importance of the country in support- METHODS ing a significantbiodiversity, mapping of the avi- fauna has not occurred and there are few data on Turkey is divided into sevengeographical regions (Fig. the statusof birds in Turkey. 1; Erol et al. 1982) characterizedby variable landscape types,climate differences,and a rich diversityof fauna Among the birds of Turkey are included 40 di- Field data were obtained from surveysconducted in all urnal birds of prey and 10 owls. -

Falco Biarmicus

International Species Action Plan Lanner Falcon Falco biarmicus Final Draft, December 1999 Prepared by BirdLife International on behalf of the European Commission International Action Plan for the Lanner Falcon Falco biarmicus Compiled by: M. Gustin, G. Palumbo, & A. Corso (LIPU / BirdLife Italy) Contributors: Alivizatos H. (HOS / BirdLife Greece), Armentano L. (Italy), Azazaf H. (Groupe Tunisien d’Ornithologie, Association “Les Amis des Oiseaux”. Tunisia), Bino T. (Albanian Society for the Protection of Birds and Mammals, Albania), Bourdakis S. (HOS / BirdLife Greece), Bousbouras D. (HOS / BirdLife Greece), Brunelli M. (S.R.O.P.U., Italy) Callaghan D. (BirdLife International, The Netherlands) Campo G. (LIPU, Italy) Ciaccio A. (LIPU Catania, Italy), Cripezzi V. (LIPU Foggia, Italy), De Sanctis A. (WWF Italia, Abruzzo regional branch, Italy), Di Meo D. (Italy) Eken G. (DHKD, Turkey), Gallo-Orsi U. (BirdLife International, The Netherlands), Giulio Bello A. (CIPR, Italy) Hallmann B. (HOS / BirdLife Greece), Hatzofe O. (Israel) Iapichino C. (LIPU, BirdLife Italy) Magrini M. (Italy), Mannino M. (LIPU, BirdLife Italy) Mingozzi T. (Univesità della Calabria, Italy) Monterosso G. (Italy) Morimando F. (Proeco, Gestione Fauna Ambiente e Territorio, Italy), Pellegrini M. (Riserva Naturale Majella Orinetale, Italy) Perna P. (Riserva Naturale Abbadia di Fiastra, Italy), Racana A. (Dipartimento Ambiente-Regione Basilicata, Italy) Rizzi V. (LIPU, Italy) Rocco M. (WWF Italy, Italy) Sigismondi A. (Italy). Stefano Bassi (Italy) Viggiani G. (Parco Nazionale Pollino, Italy) Time Table Date of first draft: 31st July 1999 Date of workshop: 1-2 October 1999 Date of final draft 31st December 1999 Reviews This action plan should be reviewed and updated every five years. An emergency review should be undertaken if sudden major environmental changes liable to affect the population occur within the range of the species. -

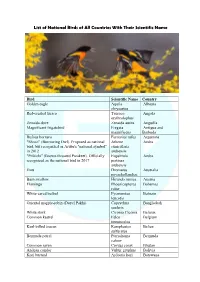

List of National Birds of All Countries with Their Scientific Name

List of National Birds of All Countries With Their Scientific Name Bird Scientific Name Country Golden eagle Aquila Albania chrysaetos Red-crested turaco Tauraco Angola erythrolophus Zenaida dove Zenaida aurita Anguilla Magnificent frigatebird Fregata Antigua and magnificens Barbuda Rufous hornero Furnarius rufus Argentina "Shoco" (Burrowing Owl). Proposed as national Athene Aruba bird, but recognized as Aruba's "national symbol" cunicularia in 2012 arubensis "Prikichi" (Brown-throated Parakeet). Officially Eupsittula Aruba recognized as the national bird in 2017 pertinax arubensis Emu Dromaius Australia novaehollandiae Barn swallow Hirundo rustica Austria Flamingo Phoenicopterus Bahamas ruber White-eared bulbul Pycnonotus Bahrain leucotis Oriental magpie-robin (Doyel Pakhi) Copsychus Bangladesh saularis White stork Ciconia Ciconia Belarus Common kestrel Falco Belgium tinnunculus Keel-billed toucan Ramphastos Belize sulfuratus Bermuda petrel Pterodroma Bermuda cahow Common raven Corvus corax Bhutan Andean condor Vultur gryphus Bolivia Kori bustard Ardeotis kori Botswana Rufous-bellied thrush Turdus Brazil rufiventris Mourning dove Zenaida British Virgin macroura Islands Giant ibis Thaumatibis Cambodia gigantea Canada jay Perisoreus Canada canadensis Grand Cayman parrot Amazona Cayman Islands leucocephala caymanensis Andean condor Vultur gryphus Chile Red-crowned crane Grus japonensis China Andean condor Vultur gryphus Colombia Clay-colored thrush Turdus grayi Costa Rica Common nightingale Luscinia Croatia megarhynchos Cuban trogon Priotelus