The Jesus Storybook Bible David A

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

PRESBYTERIANISM in AMERICA the 20 Century

WRS Journal 13:2 (August 2006) 26-43 PRESBYTERIANISM IN AMERICA The 20th Century John A. Battle The final third century of Presbyterianism in America has witnessed the collapse of the mainline Presbyterian churches into liberalism and decline, the emergence of a number of smaller, conservative denominations and agencies, and a renewed interest in Reformed theology throughout the evangelical world. The history of Presbyterianism in the twentieth century is very complex, with certain themes running through the entire century along with new and radical developments. Looking back over the last hundred years from a biblical perspective, one can see three major periods, characterized by different stages of development or decline. The entire period begins with the Presbyterian Church being overwhelmingly conservative, and united theologically, and ends with the same church being largely liberal and fragmented, with several conservative defections. I have chosen two dates during the century as marking these watershed changes in the Presbyterian Church: (1) the issuing of the 1934 mandate requiring J. Gresham Machen and others to support the church’s official Board of Foreign Missions, and (2) the adoption of the Confession of 1967. The Presbyterian Church moves to a new gospel (1900-1934) At the beginning of the century When the twentieth century opened, the Presbyterians in America were largely contained in the Presbyterian Church U.S.A. (PCUSA, the Northern church) and the Presbyterian Church in the U.S. (PCUS, the Southern church). There were a few smaller Presbyterian denominations, such as the pro-Arminian Cumberland Presbyterian Church and several Scottish Presbyterian bodies, including the United Presbyterian Church of North America and various other branches of the older Associate and Reformed Presbyteries and Synods. -

Bishop) Emailed (4) Charleston-Epis-Pod and Goodllate 2/2/19

Episcopal Church in South Carolina (Charleston, SC)—Gladstone Adams (Bishop) emailed (4) Charleston-Epis-Pod and Goodllate 2/2/19 Faith International University & Seminary (Tacoma, WA)—Michael Adams (President) faxed and emailed Tacoma and Goodlatte 2/16/19 Northeastern Ohio Synod (Cuyahoga Falls, OH) —Abraham Allende (Bishop) faxed and emailed (4) Cuyahoga Falls and Goodlatte 2/4/19 Geneva Reformed Seminary (Greenville, SC) —Mark Allison (President) emailed Greenville-Orth-Pod and Goodlatte 2/17/19 Nashotah House (Nashotah, WI) — Garwood Anderson (President) faxed and emailed (4) Nashotah and Goodlatte 2/13/19 Episcopal Diocese of California (San Francisco, CA) —Marc Andrus (Bishop) emailed (3) San Francisco-Epis-Pod and Goodlatte 2/2/19 La Crosse Area Synod (La Crosse, WI) —Jim Arends (Bishop) emailed (4) La Crosse-ELCA-Pod and Goodlatte 2/4/19 Chesapeake Bible College & Seminary (Ridgeley, MD) — Carolyn Aronson (Dean) emailed (2) Ridgeley-Orth-Pod and Goodlatte 2/17/19 Benedict College (Columbia, SC) — Roslyn Artis (President) faxed Columbia-Bapt and Goodlatte 2/9/19 North Park Theological Seminary (Chicago, IL) —Debra Auger (Dean) emailed (3) Chicago-Non-Pod and Goodlatte 2/14/19 Howard Payne University (Brownwood, TX) —Donnie Auvenshine (Dean) faxed and emailed (4) Brownwood-Pod and Goodlatte 2/9/19 Archdiocese of New Orleans (New Orleans, LA) —Gregory Aymond (Archbishop) emailed and faxed Goodlatte and New Orelans 2/1/19 Diocese of Birmingham (Birmingham, AL) —Robert Baker (Bishop) emailed (3) and faxed Goodlatte and Birmingham1/31/19 -

Certified School List MM-DD-YY.Xlsx

Updated SEVP Certified Schools January 26, 2017 SCHOOL NAME CAMPUS NAME F M CITY ST CAMPUS ID "I Am" School Inc. "I Am" School Inc. Y N Mount Shasta CA 41789 ‐ A ‐ A F International School of Languages Inc. Monroe County Community College Y N Monroe MI 135501 A F International School of Languages Inc. Monroe SH Y N North Hills CA 180718 A. T. Still University of Health Sciences Lipscomb Academy Y N Nashville TN 434743 Aaron School Southeastern Baptist Theological Y N Wake Forest NC 5594 Aaron School Southeastern Bible College Y N Birmingham AL 1110 ABC Beauty Academy, INC. South University ‐ Savannah Y N Savannah GA 10841 ABC Beauty Academy, LLC Glynn County School Administrative Y N Brunswick GA 61664 Abcott Institute Ivy Tech Community College ‐ Y Y Terre Haute IN 6050 Aberdeen School District 6‐1 WATSON SCHOOL OF BIOLOGICAL Y N COLD SPRING NY 8094 Abiding Savior Lutheran School Milford High School Y N Highland MI 23075 Abilene Christian Schools German International School Y N Allston MA 99359 Abilene Christian University Gesu (Catholic School) Y N Detroit MI 146200 Abington Friends School St. Bernard's Academy Y N Eureka CA 25239 Abraham Baldwin Agricultural College Airlink LLC N Y Waterville ME 1721944 Abraham Joshua Heschel School South‐Doyle High School Y N Knoxville TN 184190 ABT Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis School South Georgia State College Y N Douglas GA 4016 Abundant Life Christian School ELS Language Centers Dallas Y N Richardson TX 190950 ABX Air, Inc. Frederick KC Price III Christian Y N Los Angeles CA 389244 Acaciawood School Mid‐State Technical College ‐ MF Y Y Marshfield WI 31309 Academe of the Oaks Argosy University/Twin Cities Y N Eagan MN 7169 Academia Language School Kaplan University Y Y Lincoln NE 7068 Academic High School Ogden‐Hinckley Airport Y Y Ogden UT 553646 Academic High School Ogeechee Technical College Y Y Statesboro GA 3367 Academy at Charlemont, Inc. -

CS 2015.Indd

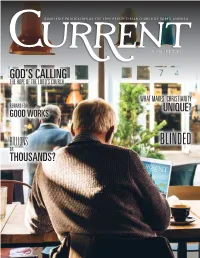

VOL. 4/No. 1 WINTER 2015 GOD’S CALLING THE HOPE OF THE LORD’S CHURCH WHAT MAKES CHRISTIANITY REWARD FOR UNIQUE? GOOD WORKS BILLIONS BLINDED OR THOUSANDS? 8 6 9 10 14 18 CONTENTS Subscriptions 3 God’s Calling: The Hope of the Lord’s Church Current is published quarterly by the Free Presbyterian Church of North America (www. 4 In Their Own Words: Rev. Anthony D’Addurno fpcna.org). The annual subscription price is $15.00 (US/CAN). To subscribe, please go to 6 Seminary Report www.fpcna.org/subscriptions. You may also subscribe by writing to Rev. Derrick Bowman, 8 Reward for Good Works 4540 Oakwood Circle, Winston-Salem, NC 27106. Checks should be made payable to Current. Billions or Thousands? 9 General Editor, Rev. Ian Goligher. Assistant Editor, Rev. Andy Foster. Copy Editor, Judy Brown. 10 Presbytery News Graphic Design, Moorehead Creative Designs. Printer, GotPrint.com. ©2015 Free Presbyterian 12 Mission Report Church of North America. All rights reserved. 14 What Makes Christianity Unique? The editor may be reached at [email protected], Church News phone: 604-897-2040, or 16 Cloverdale FPC, 18790 58 Ave., Surrey, BC V3S 9A2. 18 Blinded YOU MAY NOW READ Please consider CURRENT forwarding a link to ONLINE promote the magazine at www.fpcna.org. When at among your contacts the church website click the and friends. Current icon and choose You can still subscribe for a the format for your device. hard copy of each issue and churches may still order copies in bulk to introduce people to the magazine. -

2020 Maine SAT School Day Student Answer Sheet Instructions

2020 MAINE SAT® SCHOOL DAY Student Answer Sheet Instructions This guide will help you fill out your SAT® School Day answer you need to provide this information so that we can mail sheet—including where to send your four free score reports. you a copy of your score report.) College Board may Be sure to record your answers to the questions on the contact you regarding this test, and your address will answer sheet. Answers that are marked in this booklet will be added to your record. If you also opt in to Student not be counted. Search Service (Field 16), your address will be shared with If your school has placed a personalized label on your eligible colleges, universities, scholarships, and other answer sheet, some of your information may have already educational programs. been provided. You may not need to answer every question. If you live on a U.S. military base, in Field 10, fill in your box Your instructor will read aloud and direct you to fill out the number or other designation. Next, in Field 11, fill in the appropriate questions. letters “APO” or “FPO.” In Field 12, find the “U.S. Military Confidentiality Bases/Territories” section, and fill in the bubble for the two- letter code posted for you. In Field 13, fill in your zip code. Your high school, school district, and state may receive your Otherwise, for Field 10, fill in your street address: responses to some of the questions. Institutions that receive Include your apartment number if you have one. your SAT information are required to keep it confidential and to Indicate a space in your address by leaving a blank follow College Board guidelines for using information. -

SESSION OVERVIEW Wednesday

SESSION OVERVIEW Wednesday, November 16 Thursday, November 17 9:00- Y:40 First P.1rallcl Session Fnst Parallel Session Y:SO- 111:311 Second Parallel Session 9:20- 10:00 Second Parallel Sess•on 10:40- 11:20 Third Session 10:10-10:50 Third P<lr.?lllcl Session 11:30-12:10 Fourth Pc!rallel Sess1on II :15- 12:1 S Third Session (only 4-.1) presentations) 12:'15 . 2:00 Lunch Break 11:20-12:40 lunch Break 2:1 n- 2:50 Fourth Parallel Session 12:45 -1·15 Business Meeting - 3 :4ll Fifth Session 12:10-2.30 Break :1:50 - 4 · 30 Sixth Pclrallel Sess•on 1:15-2·15 First Session 4:40- 5:20 Seventh Parallel Sess1on 2:30- 3:10 Fifth P._lrJIIel Session 6:30. 9:00 B.:mquet and Pres•dential Address 3:20- 4 00 S•xth Parallel SeSSIOn 4:10-4:50 Seventh PJrzlllel Session Friday, November 18 5:00- 5:40 Eighth PJrallel Sess10n 7:45 · H:20 Business Session 5:40- 8:00 Dinner Break !UO- 'J:JO Fourth Plenary Scss1on 8:15- 9:15 Second Plenary Session 9:45 - 10:25 First P<1r.:1llel Session I II ::JS - II: IS Second P.lr,lllcl Sess1on 11:25-12:05 Third Parzdlel Session 1L:l5- 12:S5 f-=ourth Prlr.1llcl Sess1on Note: The Church History and Historical Theology Study Group will extend their sessions until 4:00 pm on Friday EXECUTIVE COMMITTEE OF THE EVANGEI.,ICALTHEOLOGICAL SOCIETY President Journal Editor Craig A. 8l<tising Andrc.lS Kiistcnbcrgcr Southwestern 8Jptist Theological Seminary Southmstcrn RJptist ThcolngKCJI Seminary President-Elect Demel I Kock, President, 2001 Edwin M. -

This Year from Kregel Academic

KREGEL THIS YEAR FROM ACADEMIC KREGEL ACADEMIC 288 pgs • $21.99 $12.09 Conf 400 pgs • $27.99 $15.39 Conf 288 pgs • $21.99 $12.09 Conf 432 pgs • $34.99 $19.24 Conf 352 pgs • $26.99 $14.84 Conf 464 pgs • $24.99 $13.74 Conf 704 pgs • $51.99 $28.59 Conf 544 pgs • $47.99 $26.39 Conf second edition releasing Feb 2021 CONFERENCE SPECIAL: The Text of the Earliest NT Greek Manuscripts, vols 1 & 2 $79.99 separately • $36.99 Conference Set 400 pgs • $27.99 $15.39 Conf 416 pgs • $36.99 $20.34 Conf 45% Conference discount and free shipping in the US on all Kregel books. Contact (800) 733-2607 or [email protected] to order with discount code EAS20. Offer good through Dec 31, 2020. Request free exam copies and subscribe to our monthly newsletter at KregelAcademicBlog.com. 2020 VIRTUAL ANNUAL MEETINGS November 29–December 10 FUTURE ANNUAL MEETINGS 2021 2022 2023 2024 2025 San Antonio, TX Denver, CO San Antonio, TX San Diego, CA Boston, MA November 20–23 November 19–22 November 18–21 November 23–26 November 22–25 Thanks to Our Sponsors Baker Academic and Brazos Press Baylor University Press Westminster John Knox Wipf & Stock Zondervan Zondervan NRSV Publishers Weekly 2 See the full Annual Meetings program online at www.sbl-site.org/meetings/Congresses_ProgramBook.aspx?MeetingId=37 and papers.aarweb.org/online-program-book TABLE OF CONTENTS Annual Meetings Information AAR Academy Information ........................... 81 2020 Virtual Annual Meetings .................... 4 AAR Program Sessions How to Use the Program Book .................... -

Church Profile for Prospective Executive Pastors

Spreading the Unsearchable Riches of Christ Broader in the World and Deeper in the Church. Greetings from Heritage A CHURCH PROFILE FOR PROSPECTIVE EXECUTIVE PASTORS GREENVILLE, SC WWW.HERITAGEBIBLECHURCH.ORG 1 OUR MISSION To spread the unsearchable riches of Christ broader in the world and deeper in the church. “Go therefore and make disciples of all nations, baptizing them in the name of the Father and of the Son and of the Holy Spirit, teaching them to observe all that I have commanded you ...” MATTHEW 28:19–20 “This grace was given, to preach to the Gentiles the unsearchable riches of Christ, and to bring to light for everyone what is the plan of the mystery hidden for ages in God, who created all things, so that through the church the manifold wisdom of God might now be made known … For this reason I bow my knees before the Father … that you, being rooted and grounded in love, may have strength to comprehend with all the saints what is the breadth and length and height and depth, and to know the love of Christ that surpasses knowledge ...” EPHESIANS 3:8–10, 14-19 “Of this you have heard before in the word of the truth, the gospel, which has come to you, as indeed in the whole world it is bearing fruit and increasing—as it also does among you, since the day you heard it ...” COLOSSIANS 1:5, 6 Table of Contents Section 1 Welcome to Greenville, South Carolina About Greenville Regional Church History and Culture Resources About Our Community Section 2 Meet Heritage Bible Church Nitty Gritty Facts A Gospel Church: Our first love, affiliations, and history A Bible Church: Our worship, membership, governance, and approach to discipleship A Spreading Church: Spreading the gospel to our neighbors and the nations Our Facilities Strengths, Weaknesses, & Opportunities Section 3 Our Search for an Executive Pastor 3 SECTION 1: WELCOME TO GREENVILLE, SOUTH CAROLINA Section 1 Welcome to Greenville, South Carolina About Greenville Today, the best word to describe Greenville is growth (and charm, and food). -

Newsletter 4

Inside GRS Inside GRS is the semiannual newsletter of Geneva Reformed Seminary. Vol. 2, No. 1 President’s Challenge Inside GRS Rather than offering my typical challenge related to seminary issues, I want to bring you up to date on what is happening at GRS. This is a newsletter after all. As you can see from the picture, we have made signifi- cant progress since the last issue of Inside GRS. Walls 1 that were stark are now lined with beautifully crafted bookshelves, most of which are filled with books. It is a blessing to have all our resources in one place with room to expand with freestanding bookshelves as needed. I would like to need them soon. Increasing the number of May 2008 volumes will be a constant priority and an ongoing proj- ect. I cannot conceive of ever having enough. The new classrooms were ready for the beginning of the winter term, and thanks to a generous donation we were able to furnish them nicely. The Lord has provided facilities that are both practical and attractive. Seeing the empty chairs and ample space, however, provides a daily reminder that we must see Dr. Barrett in the new GRS library the Lord bring in students to sit in those chairs and to take advantage of what is here. That continues to be the urgent need since training men to be preachers is the only reason we exist. As I’ve done before, I encourage you, therefore, to continue praying that the Lord of the Graduation invitation harvest would call laborers to His service and that He would bring some of them here for their training. -

Preparing Your Mind, Heart & Family for Seminary the Logos Bible

Knox Seminary Dallas Theological New Orleans Baptist Online vs. Brick Seminary Theological Seminary 2020 and Mortar Standing Out from a Seminary Is for You EDITION Broken World The Logos Bible Software Preparing Your Mind, Heart & Family for Seminary PG 7 Cover Option #1 C1_Generic-Download.indd 1 10/30/19 1:22 PM RANKED TOP 10 GRADUATE * PROGRAMS IN APOLOGETICS Solidly Biblical. ~TheBestSchools.org Intensely Practical. Consider Clamp Divinity School for Excellence in Ministry Preparation Proclaiming the Gospel. Equipping the Saints. Defending the Faith. • Seasoned faculty who have served as pastors and ministry leaders. NEW PROGRAM! • Highly interactive classes MA/PHD IN ARCHAEOLOGY & BIBLICAL HISTORY online or on campus. Join in VIU’s excavation of biblical history at our Tall el-Hammam (Sodom) site in Jordan! The Tall el-Hammam Excavation Project (TeHEP) is a joint scientific project between Veritas International University School of Archaeology, Trinity Southwest University, and the Department of • Affordable Master-level Antiquities of the Hashemite Kingdom of Jordan. courses at $350/hour. • Anderson University is ranked in the top-tier of Southern Regional Universities according to US News and World Report. Degree options: Master of Divinity (75hrs) CLAMP Master of Ministry (36hrs) Master of Ministry divinity Fully Accredited Degree Programs! Management (30hrs) school VIU Norman L. Geisler anderson university VIU School of Archaeology Veritas College & Seminary Doctor of Ministry in Biblical School of Apologetics MA in Archaeology BA in Christian Studies Preaching (35hrs) MA in Apologetics & Biblical History MA in Theological Studies Learn more at MDiv in Apologetics PhD in Archaeology MA in Biblical Studies st Doctor of Ministry in 21 DMin in Apologetics & Biblical History MDiv in Biblical Studies Century Ministry (35hrs) CLAMPDIV.COM Residential and Distance Learning Options Available! 3000 W. -

Seminary Bulletin

Geneva Reformed Seminary BULLETIN 2012-2014 Volume 9 A Word from the Interim President reaching and teaching the Word of God is serious business. Shepherding members of God’s flock is a sobering task given P that He has purchased it with His own blood. Given what is involved and what is at stake, entering the ministry prematurely is unwise at best and hazardous at worst. Preparation is vital and an integral part of the calling of each minister. Geneva Reformed Seminary exists to train and prepare prospective preachers for the ministry of the gospel. GRS seeks to equip men to skillfully handle the Word of God and to sharpen their gifts to be more effective in ministry for the glory of God and the good of His people. GRS is conscious of what its limitations are. We desire to cultivate the gifts of students and provide the necessary tools for ministry. But we cannot make our students godly. However, we do want GRS to be a place where striving after godliness is encouraged, and keeping students aware of their need for dependency on the Holy Spirit is emphasized. As has been emphasized throughout the history of GRS, connecting the head and the heart—the intellect and devotion—is a major concern in every aspect of the seminary’s course. One of the benefits of GRS is its link to the local church, and we encourage each student to be actively involved in a local church. GRS is committed to connecting orthodoxy and practice. We affirm the biblical, historical, Reformed, and Protestant faith. -

Certified School List 11-05-2014.Xlsx

Updated SEVP Certified Schools November 5, 2014 SCHOOL NAME CAMPUS NAME F M CITY ST CAMPUS ID "I Am" School Inc. "I Am" School Inc. Y N Mount Shasta CA 41789 424 Aviation 424 Aviation N Y Miami FL 103705 ‐ A ‐ A F International School of Languages Inc. A F International of Westlake Y N Westlake Village CA 57589 Village A F International School of Languages Inc. A F International College Y N Los Angeles CA 9538 A. T. Still University of Health Sciences Kirksville Coll of Osteopathic Y N Kirksville MO 3606 Medicine Aaron School Aaron School Y N New York NY 114558 Aaron School Aaron School ‐ 30th Street Y N New York NY 159091 ABC Beauty Academy, INC. ABC Beauty Academy, INC. N Y Flushing NY 95879 ABC Beauty Academy, LLC ABC Beauty Academy N Y Garland TX 50677 Abcott Institute Abcott Institute N Y Southfield MI 197890 Aberdeen Catholic School System Roncalli Y N Aberdeen SD 21405 Aberdeen Catholic School System Roncalli Elementary Y N Aberdeen SD 180511 Aberdeen Catholic School System Roncalli Primary Y N Aberdeen SD 180510 Aberdeen School District 6‐1 Aberdeen Central High School Y N Aberdeen SD 36568 Abiding Savior Lutheran School Abiding Savior Lutheran School Y N Lake Forest CA 9920 Abilene Christian Schools Abilene Christian Schools Y N Abilene TX 8973 Abilene Christian University Abilene Christian University Y N Abilene TX 7498 Abington Friends School Abington Friends School Y N Jenkintown PA 20191 Above It All, Inc Benchmark Flight /Hawaii Flight N Y Kailua‐Kona HI 24353 Academy Abraham Baldwin Agricultural College Tifton Campus Y N Tifton GA 6931 Abraham Joshua Heschel School Abraham Joshua Heschel School Y N New York NY 106824 ABT Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis School ABT Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis Y Y New York NY 52401 School Abundant Life Academy Abundant Life Academy‐Virginia Y N Milford VA 81523 Abundant Life Christian School Abundant Life Christian School Y N Madison WI 24403 ABX Air, Inc.