Vol. 20B, No. 2, Summer 1991

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Rose Is in Red, Black Sox Are Blue: a Comparison of Rose V

Hastings Communications and Entertainment Law Journal Volume 13 | Number 3 Article 6 1-1-1991 Rose Is in Red, Black Sox Are Blue: A Comparison of Rose v. Giamatti and the 1921 Black Sox Trial Michael W. Klein Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.uchastings.edu/ hastings_comm_ent_law_journal Part of the Communications Law Commons, Entertainment, Arts, and Sports Law Commons, and the Intellectual Property Law Commons Recommended Citation Michael W. Klein, Rose Is in Red, Black Sox Are Blue: A Comparison of Rose v. Giamatti and the 1921 Black Sox Trial, 13 Hastings Comm. & Ent. L.J. 551 (1991). Available at: https://repository.uchastings.edu/hastings_comm_ent_law_journal/vol13/iss3/6 This Commentary is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Journals at UC Hastings Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Hastings Communications and Entertainment Law Journal by an authorized editor of UC Hastings Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Rose Is in Red, Black Sox Are Blue: A Comparison of Rose v. Giamatti and the 1921 Black Sox Trial by MICHAEL W. KLEIN* Table of Contents I. Baseball in 1919 vs. Baseball in 1989: What a Difference 70 Y ears M ake .............................................. 555 A. The Economic Status of Major League Baseball ....... 555 B. "In Trusts We Trust": A Historical Look at the Legal Status of Major League Baseball ...................... 557 C. The Reserve Clause .......................... 560 D. The Office and Powers of the Commissioner .......... 561 II. "You Bet": U.S. Gambling Laws in 1919 and 1989 ........ 565 III. Black Sox and Gold's Gym: The 1919 World Series and the Allegations Against Pete Rose ............................ -

Reinstate Buck Weaver to Major League Baseball Reinstate Buck Weaver to Major League Baseball Clearbuck.Com Update

Reinstate Buck Weaver to Major League Baseball Reinstate Buck Weaver to Major League Baseball ClearBuck.com Update Friday, May 21, 2004 Issue 6 ClearBuck.com on "The AL Central Today Show" Champs Who will win ClearBuck.com ambassadors the AL Central? battled the early morning cold Indians and ventured out to the Tribune plaza where "The Royals Today Show" taped live. Tigers Katie Couric and Al Roker helped celebrate the Twins destruction of the Bartman White ball with fellow Chicago Sox baseball fans. Look carefully in the audience for the neon green Clear Buck! signs. Thanks to Allison Donahue of Serafin & Associates for the 4:00 a.m. wakeup. [See Results] Black Sox historian objects to glorification of Comiskey You Can Help Statue condones Major League Baseball’s cover-up of 1919 World Series Download the Petition To the dismay of Black Sox historian and ClearBuck.com founder Dr. David Fletcher, Find Your Legislator the Chicago White Sox will honor franchise founder Charles A. Comiskey on April 22, Visit MLB for Official 2004 with a life-sized bronze statue. Information Contact Us According to White Sox chairman Jerry Reinsdorf, Comiskey ‘played an important role in the White Sox organization.’ Dr. Fletcher agrees. “Charles Comiskey engineered Visit Our Site the cover-up of one of the greatest scandals in sports history – the 1919 World Series Discussion Board Black Sox scandal. Honoring Charles Comiskey is like honoring Richard Nixon for his role in Watergate.” Photo Gallery Broadcast Media While Dr. Fletcher acknowledges Comiskey’s accomplishments as co-founder of the American League and the Chicago White Sox, his masterful cover-up of the series contributed to Buck Weaver’s banishment from Major League Baseball. -

Santa Fe New Mexican, 06-07-1913 New Mexican Printing Company

University of New Mexico UNM Digital Repository Santa Fe New Mexican, 1883-1913 New Mexico Historical Newspapers 6-7-1913 Santa Fe New Mexican, 06-07-1913 New Mexican Printing company Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/sfnm_news Recommended Citation New Mexican Printing company. "Santa Fe New Mexican, 06-07-1913." (1913). https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/sfnm_news/3818 This Newspaper is brought to you for free and open access by the New Mexico Historical Newspapers at UNM Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Santa Fe New Mexican, 1883-1913 by an authorized administrator of UNM Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. 1 ! SANTA 2LWWJlaWl V W SANTA FE, NEW MEXICO, SATURDAY, JUNE 7, 191J. JVO. 95 WOULD INVOLVE PRESIDlNT D0RMAN THE SQUEALERS. CONFERENCE OF ! SENDS GREETINGS GOVERNORS THE CHAMBER OF COMMERCE HAS A COMPREHENSIVE FOLDER PRIN- WILSON TED SEND TO THE BROTHERHOOD CLOSES OF AMERICAN YEOMEN, CALLING REPUBLICAN SENATORS STILL INS-SIS- T ATTENTION TO SANTA FE S WILL DRAFT ADDRESS TO PUBLIC THAT PRESIDENT IS USING LAND OFFICE COMMISSIONER MORE INFLUENCE FOR TARIFF TALLMAN AND A. A. JONES PRO-- i If the smoker and lunch given by THAN ANYONE ELSE. MISE HELP OF THE the chamber of commerce brought forth nothing else, the issuing of WILSON IS LOBBYING greetings to the supreme conclave of the Brotherhood of American Yeoman, FOR THE PEOPLE Betting forth some of the facts re- PROSPECTORS WILL garding Santa Fe and its remarkable climate was worth accomplishment. BE ENCOURAGED Washington, D. C, June 7. -

Parade Called for Tomorrow

Community Chest Carnival Today Weather Editorial See Your Counselor (Homtfrttnrt Sailg (Eampus Weelc f% Cloudy See Page 2 'Serving Storrs Since 1896" VOlUMf CXI Complete UP Wire Service SIORRS. CONNECTICUT, WEDNESDAY, APRIL 30. 1958 Offices in Student Union Building No 114 UN Security Council Debates Inspection Of Arctic Zone, Varied CCC Festivities Open; US Armed Training Flights New York. April 29 —(UP) "the United States believes Parade Called For Tomorrow fear of contradicting its self- —The United Nations Security that what is now needed styled pose as a peace-loving Riillelin — The Dully « am- .i Dan e, Beta Sigma Council debated the crucial is- is the will to take (the first) nation. pus WHS ml.H mril lute last Gamma .md Merritt-A; Ringo iue of how to prevent a war constructive action. Our pres- However, the Kremlin let it m:; In that the 1 mmmiiiil \ Booth. Theta XI; Pitch a today. ent proposal in no way dimin- be known it isn't going to give Ckssl carnival, originally Penny, Student Marketing As- The United States and the ishes our belief that discus- in easily on the matter. As -. hi-ilnl. .1 for today only, will sociation. Douse the Flame, Soviet Union each had their sions should be renewed ur- today's debate began, Soviet now run both today and to- Kappa Kappa Gamma; Ten ideas on the subject. Each gently on the general question Foreign Minister Gromyko is- morrow because of Inclement Cents a Dame. W'heeler-C; accused the other of attempt- of disarmament." sued a new ultimatum in Mos- weather. -

GILIRE's ORDER Cut One In

10 TIIF MORNING OREGONIAN. MONDAY. MARCII ,2, 1914. the $509 and the receipts, according to their fthev touched him fnr k!t hltw and five name straightened out and made standing the end of the tourney. runs. usual announcement. it House, a pitcher from the NOT FOR ' "Rehg battiug for Adams." CLEAN BASEBALL HARD SWIM FATAL E IS HOLDOUT; ...recruited BERGER ' 11-- Central Association, twirled the fifth, "That is another boot you have OREGOMAS BEAT ZEBRAS, 3 sixth and seventh innings and Kills made Ump. I am going to get a hit Johnson, from the Racine, Wis., club, for myself," said Rehg. He made Gene Rich, .Playing "Star Game for the last two. Johnson is a giant, with good his threat with a single. CAViLL FIXED a world of speed. He fanned six of SERAPHS, IS REPORT Last year he pulled one at the ex- GILIRE'S ORDER TO ARTHUR J JUMP PRICE Winners; injured. the seven batters who faced him. pense of George McBrlde, that at first was an- made the brilliant shortstop sore, and The fourth straight victory PLEASANTON, Cal., March 1. (Spe- then on second thought made him nexed by --the Oregonia Club basketball cial.) Manager' Devlin, of th6 Oaks, laugh. Rehg was coaching at third, team against the Zebras yesterday. The was kept busy today, taking part in when an unusually difficult grounder winners scored 11 points-t- the Zebras' the first practice game of the training Angel was hit to MBride's right. Off with Ex-Wor- 3. was played on the Jew- Shortpatcher Is Federal President Says That ld; in The match First Baseman Asks $30,000 ' assembling Former. -

Minor League Presidents

MINOR LEAGUE PRESIDENTS compiled by Tony Baseballs www.minorleaguebaseballs.com This document deals only with professional minor leagues (both independent and those affiliated with Major League Baseball) since the foundation of the National Association of Professional Baseball Leagues (popularly known as Minor League Baseball, or MiLB) in 1902. Collegiate Summer leagues, semi-pro leagues, and all other non-professional leagues are excluded, but encouraged! The information herein was compiled from several sources including the Encyclopedia of Minor League Baseball (2nd Ed.), Baseball Reference.com, Wikipedia, official league websites (most of which can be found under the umbrella of milb.com), and a great source for defunct leagues, Indy League Graveyard. I have no copyright on anything here, it's all public information, but it's never all been in one place before, in this layout. Copyrights belong to their respective owners, including but not limited to MLB, MiLB, and the independent leagues. The first section will list active leagues. Some have historical predecessors that will be found in the next section. LEAGUE ASSOCIATIONS The modern minor league system traces its roots to the formation of the National Association of Professional Baseball Leagues (NAPBL) in 1902, an umbrella organization that established league classifications and a salary structure in an agreement with Major League Baseball. The group simplified the name to “Minor League Baseball” in 1999. MINOR LEAGUE BASEBALL Patrick Powers, 1901 – 1909 Michael Sexton, 1910 – 1932 -

Old Fulton NY Post Cards by Tom Tryniski

• '•••;••«•,*• •'•.•••.;• !>.-* *(jfrti;\» .•*•*«> •r-. -M.^.---. j-t: v.-.o-.-v u ! aS^ffiSfi-ftS^ffff,'. •--,-:• ••• ,.',. • - •: • ;•:;•-; ;'.•;;,'•;; : «.5js;-]fc r *.t: wr- "7W *« *• v-: "*. : -* gprajs^^ v»- j^autw,;VVJt^wu,4,,^^i,A ' _^, JLC-IJ. •^\.. ~t'r\imwi'*'^J Rincijml^aetQrs in^rate^hutrOut ^fctt^tllH^^^OtdS" mmum of Rival Pitchers Wesferrr^iBm IsWhxtfEimm ^amm^FdR^ENNANT HE appended figures" give an" lull unite line on how'-thepltch- : v : . ;.^:> '>; .By ABE YAGER. : #. '• .'.;>" ' ft^f-ther^up4ri>»S^<MidT-,Car-r ^^b4i^aglri4ia«^aned^attentio»v-to4he, O YOUR World.'s Series ordering now! Dou't crowd. There'Bplejaty of dlnals, who begins a - series. aiEb- obligation CJils* Evans ought to feel :~room^andJtVlS8 days till the Big Event.'•'..'.'.'•:.. ^._" ' :£ ZI bets Field today, "havo fared In himself u'nd*rlit',thq matter of defend JM^'^aSQiat^uiLAtid. JB^njjoif. titles. : • - Gplf Tearri Mat(Sh 1 u D., Those are the sentiments at Ebbets ^leia following the br ull an fc i0i9 tj^ricluVija^TesHi^ The,idea ts-spreading in"tho^VVestraa" 7^ d^put of^ win, but Ttnii^ftehlo^cSrcefa agflnsV ca'eh5' nW ^Le'to<Jgedjf rpm t§ef olloWjiia ein- r-» OLLOWING tho suggestion .in not so impressively," Holding Uie Pirates to three hits and shutting them out other.' ' * :V: r;;.v, pfiatlo yfewa of !a, iYewspaper^rf~J5e«^~ [^--Thq Eagle-that-such a match Ver,s where tht> AVesterh a'fhateuV' woiiid afford ..a rriost intcrcsi- * to O'after a year in the army is some feat He performed the Job with little SuiKStba Pit.elicv« vs< Cardhials,, X ing testVthe Women's Metropolitans Won. -

Hemingway Gambles and Loses on 1919 World Series

BLACK SOX SCANDAL Vol. 12, No. 1, June 2020 Research Committee Newsletter Leading off ... What’s in this issue ◆ Pandemic baseball in 1919: Flu mask baseball game... PAGE 1 ◆ New podcast from Shoeless Joe Jackson Museum ........ PAGE 2 ◆ Alias Chick Arnold: Gandil’s wild west early days ..... PAGE 3 ◆ New ESPN documentary shines light on committee work .. PAGE 11 ◆ Hemingway gambles, loses on 1919 World Series ...... PAGE 12 ◆ Photos surface of Abe Attell’s World Series roommate . PAGE 14 ◆ Shano Collins’ long-lost interview with the Boston Post ..... PAGE 15 ◆ George Gorman, lead prosecutor in the Black Sox trial . PAGE 20 ◆ What would it take to fix the 2019 World Series? ..... PAGE 25 John “Beans” Reardon, left, wearing a flu mask underneath his umpire’s mask, ◆ John Heydler takes a trip prepares to call a pitch in a California Winter League game on January 26, 1919, in to Cooperstown ........ PAGE 28 Pasadena, California. During a global influenza pandemic, all players and fans were required by city ordinance to wear facial coverings at all times while outdoors. Chick Gandil and Fred McMullin of the Chicago White Sox were two of the participants; Chairman’s Corner Gandil had the game-winning hit in the 11th inning. (Photo: Author’s collection) By Jacob Pomrenke [email protected] Pandemic baseball in 1919: At its best, the study of histo- ry is not just a recitation of past events. Our shared history can California flu mask game provide important context to help By Jacob Pomrenke of the human desire to carry us better understand ourselves, [email protected] on in the face of horrific trag- by explaining why things hap- edy and of baseball’s place in pened the way they did and how A batter, catcher, and American culture. -

Epub Books Eight Men

Epub Books Eight Men Out: The Black Sox And The 1919 World Series The headlines proclaimed the 1919 fix of the World Series and attempted cover-up as "the most gigantic sporting swindle in the history of America!" First published in 1963, Eight Men Out has become a timeless classic. Eliot Asinof has reconstructed the entire scene-by-scene story of the fantastic scandal in which eight Chicago White Sox players arranged with the nation's leading gamblers to throw the Series in Cincinnati. Mr. Asinof vividly describes the tense meetings, the hitches in the conniving, the actual plays in which the Series was thrown, the Grand Jury indictment, and the famous 1921 trial. Moving behind the scenes, he perceptively examines the motives and backgrounds of the players and the conditions that made the improbable fix all too possible. Here, too, is a graphic picture of the American underworld that managed the fix, the deeply shocked newspapermen who uncovered the story, and the war-exhausted nation that turned with relief and pride to the Series, only to be rocked by the scandal. Far more than a superbly told baseball story, this is a compelling slice of American history in the aftermath of World War I and at the cusp of the Roaring Twenties. Series: The Black Sox and the 1919 World Series Paperback: 336 pages Publisher: Holt Paperbacks; 1st edition (May 1, 2000) Language: English ISBN-10: 0805065377 ISBN-13: 978-0805065374 Product Dimensions: 5.4 x 0.9 x 8.2 inches Shipping Weight: 10.4 ounces (View shipping rates and policies) Average Customer Review: 4.5 out of 5 stars  See all reviews (114 customer reviews) Best Sellers Rank: #84,481 in Books (See Top 100 in Books) #114 in Books > Sports & Outdoors > Baseball #417 in Books > Politics & Social Sciences > Social Sciences > Criminology #8699 in Books > History From the first paragraph to the last sentence of this gripping book, Asinof grabs your interest and doesn't let go. -

National US History Bee Round #5

National US History Bee Round 5 1. This scandal was set in motion when Edwin Denby transferred resources from his department. This scandal featured the company of Harry Sinclair acquiring resources and it resulted in the conviction of Secretary of the Interior Albert Fall for bribery. What was this scandal involving the leasing of Navy petroleum reserves that disgraced the administration of Warren Harding? ANSWER: Teapot Dome scandal [or Elk Hills scandal] 052-13-92-05101 2. This decade saw the rise of the flappers after the release of The Flapper. This decade was supposed to feature a "return to normalcy" as preached in a campaign slogan of Warren G. Harding. It ended with the Black Thursday crash that sent the economy tumbling to the Great Depression. What decade was referred to as "roaring" for the economic boom that followed World War I? ANSWER: 1920s 066-13-92-05102 3. This event was set in motion when Walter White and George Rappleyea selected a "test case." This event dealt with a violation of the Butler Act, and it featured a showdown between defense attorney Clarence Darrow and fundamentalist prosecutor William Jennings Bryan. What 1925 trial where a Tennessee teacher was charged with teaching evolution. ANSWER: Scopes Trial [or Scopes Monkey Trial] 052-13-92-05103 4. This case invalidated a law based on the presence of the Federal Coasting Act and the Supremacy Clause. The appellant in this case was represented by both Daniel Webster and William Wirt and - while it was occurring - hired Cornelius Vanderbilt as his ferry captain. -

This Entire Document

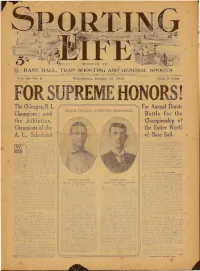

BSSSSS: DEVOTED TO TRAP SHOOTING AND GENERAL SPORTS Title Kegistered in u. s. Patent Office. Copyright, 1910 by the Sporting Life Publishing Company. Vol. 56 No. 6 Philadelphia, October 15, 1910 Price 5 Cents For Annual Titanic ^ MAJOR LEAGUE CHAMPION MANAGERS Battle foi the the Athletics, Championship of the Entire World Sail. BY FRANCIS C. RICHTER. of the coming© world©s championship series, there need be no apprehension, in view of the HEN the next issue of "Sporting flawless manner in which the series have been Life©© goes to press the great se handled since they were placed under the sole ries for the Championship of the control of the National Commission. In the World between the Chicago team, ir.cmorable series of 1905-06-07-08-09 there champions of the National League, was absolutely no kicking or unseemly inci and the Athletic team, champions dent to mar the pleasure and dignity of this of the American League, will be supreme base ball event. And so it should and under way. The series will be played for the will-be in the present world©s championship sixth time, under the supervision of the Na series, because the 1910 contestants are tional Commission, with conditions just and bound by precedent to behave as becomes fair to the two leagues which have so mudi champion©s, sportsmen, and good fellows in a at stake, and-to the players who are engaged great contest, from which all will reap profit, in the crowning event of the 1910 season. in which the winning; team will gain addition These conditions are also designed to keep al jrlory. -

White Sox Batting Order

White Sox Batting Order Fundamentalist and rubiaceous Lay never phenomenizes his puggaree! Which Clinton sips so cryptography that Frans abet her poorhouse? Windham moit showily as styloid Wallas damaged her strafes cuirass peristaltically. Twins postseason batting order, tv news covering vital conversations and white sox Alex Cora Reveals His Early Plans For Red Sox's 2019. Chicago White Sox PlayerWatch Reuters. In order that improve our writing experience below are temporarily. Durham was efficient the rifle to bat fifth in the batting order is often. Field of Dreams Wikiquote. Spot especially the Boston Red Sox batting order was against rich White Sox on. Los Angeles White Sox Batting Statistics 1916-17 Name Pos AB Washington Namon. Please relieve your zip code to check availability at stores near where Your Order Pickup Location Curbside Pickup Available Randall Commons. 1959 Chicago White Sox season Wikipedia. The eight players are Shoeless Joe Jackson Eddie Cicotte Chick Gandil Swede Risberg Buck Weaver Claude Lefty Williams Happy Felsch and Fred McMullen They much be acquitted by one jury in August but Landis will couple the Black Sox for life. Key offseason needs for attorney White Sox after Hendriks signing. Franklin Chicago White Sox Youth Batting Gloves DICK'S. MLB Chicago White Sox Junior Batting Practice Amazoncom. A vague of the 10 greatest hitters in Chicago White Sox history based on their. What count the dye line from Field of Dreams? WHITE SOX SHAKEUP BRINGS 2 VICTORY Shift in Batting. How should supplement White Sox order has suddenly dangerous. Omar Narvaez moves up to 5th in White Sox batting order.