805 Transcript

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

International Zoo News Vol. 50/5 (No

International Zoo News Vol. 50/5 (No. 326) July/August 2003 CONTENTS OBITUARY – Patricia O'Connor EDITORIAL FEATURE ARTICLES Reptiles in Japanese Collections. Part 1: Ken Kawata Chelonians, 1998 Breeding Birds of Paradise at Simon Bruslund Jensen and Sven Hammer Al Wabra Wildlife Preservation An Artist Visits Two Chinese Zoos Frank Pé Variation in Reliability of Measuring Tony King, Elke Boyen and Sander Muilerman Behaviours of Reintroduced Orphan Gorillas Letter to the Editor Book Reviews Conservation Miscellany International Zoo News Recent Articles * * * OBITUARY Patricia O'Connor Dr Patricia O'Connor Halloran made history when she took the position of the staff veterinarian of the Staten Island Zoo, New York, in 1942: she became the first full-time woman zoo veterinarian (and, quite possibly, the first woman zoo veterinarian) in North America. She began her zoo work at a time when opportunities for career-oriented women were limited. Between 1930 and 1939, only 0.8 percent of graduates of American and Canadian veterinary schools were women (the figure had increased to more than 60 percent by the 1990s). At her husband's suggestion she continued to use her maiden name O'Connor as her professional name. For nearly three decades until her retirement in 1970 she wore many hats to keep the zoo going, especially during the war years. She was de facto the curator of education, as well as the curator of mammals and birds. A superb organizer, she helped found several organizations, including the American Association of Zoo Veterinarians (AAZV). Dr O'Connor became the AAZV's first president from 1946 to 1957, and took up the presidency again in 1965. -

October 2007 News from Pandas International

October 2007 News from Pandas International Pandas International October 2007 Newsletter ABOUT US :: PRODUCTS :: EDUCATIONAL PROGRAMS :: LEARNING ACTIVITIES :: PANDA PHOTOS DONATE NOW :: ADOPT A PANDA :: BECOME A MEMBER This newsletter will focus on two stories of individuals who Note: Due to traveling to China, major health problems, volunteered at Wolong this year, their thoughts, their and an auto accident, we have not gotten out our monthly experience, and their love for pandas. newsletters. If you are interested in volunteering check our web site http:// We have so much to tell you about Suzanne’s trip to www.pandasinternational.org/volunteer.html Wolong, the new cubs at Wolong and various other panda stories, we will send two newsletters a month till we get you caught up on all the news.! Our Summer Vacation The giant panda cub who by Rebecca & Richard Johnston, Wolong Volunteers didn’t make it, but left a As frequently and most aptly stated by panda keepers at the legacy of love San Diego, CA Zoo, I too have been having a love affair with the Giant Panda for some time now. Not since 1987 as in the by Chet Chin, Wolong Volunteer and Panda Parent case of the San Diego Zoo, but since 1999 when Hua Mei, When he was born, he made headlines around the world, not born in San Diego of parents Bai Yun and Shi Shi, received just because he was a giant panda cub, but because he was the title of “first panda to be born and survive to adulthood in the first giant panda cub to be born with a harelip. -

Frozen Zoo May Hold Hope for Saving the Northern White Rhino

Frozen Zoo may hold hope for saving the northern white rhino By TONY PERRY JANUARY 23, 2015, 7:07 PM | REPORTING FROM SAN DIEGO ola is eating her morning meal of apples and grain and appears ready to take her N antibiotic pills. After feeling poorly for a couple of weeks, she is moving around. This is welcome news to Nola's devoted keepers at the San Diego Zoo Safari Park. She is one of only five northern white rhinos left on Earth: three of the others are in a preserve in Kenya, and one is in a zoo in the Czech Republic. Nola's recent illness, coming just weeks after the unanticipated death of Angalifu, the park's male northern white rhino, was a pointed reminder of the fragility of her species. At 40, even with care, Nola is near the end of her expected life span, and breeding is no longer seen as an option. Efforts in Kenya to mate the male and the two females have been unsuccessful. But scientists working for the zoo's Institute for Conservation Research say hope may yet exist for the northern white rhino: futuristic technology that might allow it to make a comeback even after the remaining animals are gone. The strategy — a long shot, researchers acknowledge — involves frozen specimens of reproductive material and a surrogate rhino mother from a different subspecies. "You have to be optimistic, but you have to be willing to accept that you're going to fail sometimes," said Barbara Durrant, director of reproductive physiology at the institute. -

Stow-Munroe Falls Public Library

Stow-Munroe Falls Public Library http://a1.smfpl.org/prevsite/mar-07.htm SMFPL Logo Library News Stow-Munroe Falls Public Library 3512 Darrow Road Stow, OH 44224 Phone: (330) 688-3295 Fax: (330) 688-0448 About AJMenu This edition of LIBRARY E-NEWS is sponsored by: Stow-Munroe Falls Public Library 3512 Darrow Rd. Stow, Ohio 44224 Phone (330) 688-3295 Fax (330) 688-0448 www.smfpl.org Welcome to the March 2007 edition of LIBRARY E-NEWS . This monthly newsletter includes several features containing information about the library. If you would like to join other subscribers in receiving the Library E-News in your e-mail every month, please fill out the following form online or complete a paper registration form at the circulation desk. For a complete calendar of events at Stow-Munroe Falls Public Library go to www.smfpl.org/calendar.htm Go directly to the following features by clicking on the name of the feature you want to read, or scroll down this page to read all of LIBRARY E-NEWS . Notices Upcoming Special Events Recent Library Happenings New Titles Department News Art on Display Library Foundation Friends of the Library Quilt on Display Spotlight on Netlibrary Staff Picks Film Recommendations Website of the Month Previous Issues Notices Coffee With the Editor The next Coffee With the Editor will be Wednesday, April 4 from 9:00 to 10:00 a.m. Library Fence Workers will soon be tearing down and replacing the fence along the back side of the library parking. Please do not park in this area until the work is completed. -

Final GP Genetic Recommendations 2008

Report to: Chinese Association of Zoological Gardens (CAZG) Giant Panda Office, Department of Wildlife Conservation, State Forestry Administration Giant Panda Conservation Foundation (GPCF) 2013 Breeding and Management Recommendations and Summary of the Status of the Giant Panda Ex Situ Population 13 - 15 November 2012 Chengdu, China Submitted by: Kathy Traylor-Holzer, Ph.D. Jonathan D. Ballou, Ph.D. IUCN/SSC Conservation Breeding Specialist Group Chinese translation provided by: Yan Ping Sponsored by: Smithsonian Conservation Biology Institute Executive Summary This is a report on the meeting held 13 - 15 November 2012 in Chengdu, China to update the analysis of the ex situ population of giant pandas and develop breeding recommendations for the 2013 breeding season. This is the 11th annual set of genetic management recommendations developed for giant pandas. The current ex situ population of giant pandas consists of 341 animals (154 males, 184 females, 3 unsexed pandas) located in 66 institutions worldwide. In 2012 there were 28 births and 18 deaths. The genetic status of the population is currently healthy, with 51 founders represented and another 14 that could be genetically represented if they were to successfully breed. There are only 3 inbred animals with inbreeding coefficients > 3% in the population. There are 55 giant pandas in the studbook that are living or have living descendents and for which the sire is unknown or uncertain. Most of these are pandas that were born in 2006 or later and are the result of natural mating and/or artificial insemination with multiple males. The result is that 11% of the gene pool of the ex situ population is derived from uncertain ancestry. -

An Introduction to Zoological Multiplicity in the Modern American Zoo Emily D

Claremont Colleges Scholarship @ Claremont Scripps Senior Theses Scripps Student Scholarship 2017 Menageries Multiple: An Introduction to Zoological Multiplicity in the Modern American Zoo Emily D. Gratke Scripps College Recommended Citation Gratke, Emily D., "Menageries Multiple: An Introduction to Zoological Multiplicity in the Modern American Zoo" (2017). Scripps Senior Theses. 1059. http://scholarship.claremont.edu/scripps_theses/1059 This Open Access Senior Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Scripps Student Scholarship at Scholarship @ Claremont. It has been accepted for inclusion in Scripps Senior Theses by an authorized administrator of Scholarship @ Claremont. For more information, please contact [email protected]. MENAGERIES MULTIPLE: AN INTRODUCTION TO ZOOLOGICAL MULTIPLICITY IN THE MODERN AMERICAN ZOO by EMILY D. GRATKE SUBMITTED TO SCRIPPS COLLEGE IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE DEGREE OF BACHELOR OF ARTS PROFESSOR PERINI PROFESSOR WILLIAMS APRIL 21, 2017 i CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS INTRODUCTION Methodology and Term Definition CHAPTER ONE. Zoological Multiplicity through Time The Emergence of Pet Keeping The Growth of the American Zoo The Development of the Modern Animal Rights Movement Moving on to Modern Multiplicity CHAPTER TWO. Animals in Action: Contemporary Manifestations of Multiplicity The Perception of the Zoogoer The Perception of the Activist The Perception of the Zoo The Meaning of Multiplicity CHAPTER THREE. The Effects of Zoological Multiplicity CONCLUSION AND FUTURE WORK Bibliography ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to first thank Professor Perini for her continuous support, guidance, and mentorship throughout this project. I would also like to thank Professor Williams for her assistance in the reading and editing processes, as well as Professor de Laet for her help in shaping the framework of my thesis. -

San Diego Zoo Panda Gives Birth to 5Th Cub 5 August 2009, by ELLIOT SPAGAT , Associated Press Writer

San Diego Zoo panda gives birth to 5th cub 5 August 2009, By ELLIOT SPAGAT , Associated Press Writer that I would know, but she didn't have seemingly as much discomfort or moving about as what we've seen in the past," she said. Bai Yun seemed comfortable with the cub and appeared to start nursing about 30 minutes after birth. "She knows she's been there, done that," Sutherland-Smith said. A second fetus had been detected, but it was probably absorbed in the mother's uterus. This image provided by the San Diego Zoo shows a new panda birth, upper right, captured Wednesday Aug. 5, The pink, nearly hairless panda newborn weighed 2009 via a closed-circut camera in the birthing den in the about 4 ounces and is about the size of a stick of zoo in San Diego. It was the fifth birth for mother, Bai butter. Its gender won't be known for several Yun. The sex of the mostly hairless, pink newborn, which weeks, until officials can get a better look, and it is about the size of a stick of butter, will not be known for won't get a name for 100 days, in line with Chinese some time, and it will be approximately one month tradition. before the iconic black-and-white coloration of a giant panda becomes visible. (AP Photo/San Diego Zoo, Ken Mom and cub will lead private lives for the next four Bohn) months or so, but they will appear on the zoo's live Panda Cam, which can be watched online. -

Giant Pandas

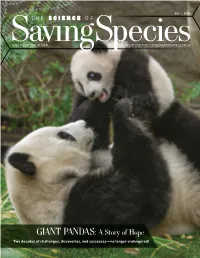

VOL. 1 | 2017 THE SCIENCE OF SAN DIEGO ZOO GLOBAL INSTITUTE FOR CONSERVATION RESEARCH GIANT PANDAS: A Story of Hope Two decades of challenges, discoveries, and successes—no longer endangered! Both of our experiences exemplified an essential lesson learned for international collaboration: if you make friends first, More than two decades of GIANT PANDAS: science and teamwork will follow. experience with panda –RON SWAISGOOD, PH.D., AND MEGAN OWEN, PH.D. behavior, diet, breeding, and reproduction in partnership with our Chinese colleagues The Road to Recovery has led to new discoveries BY RON SWAISGOOD, PH.D., DIRECTOR OF RECOVERY ECOLOGY, that have made the future AND MEGAN OWEN, PH.D., ASSOCIATE DIRECTOR OF RECOVERY ECOLOGY Still Saving Giant Pandas much brighter for the Outside of China, San Diego Zoo’s giant panda breeding program is second to none. giant panda. Two decades ago, we could hardly imagine that the giant panda would Our lovely matriarch, Bai Yun, has given birth to six healthy cubs at the Zoo and now has one day be downlisted from Endangered to Vulnerable. San Diego 14 grandcubs back in China, including one great-grandcub! Adding to that accomplishment Zoo Global is proud to have played an important role in setting the is the tremendous body of knowledge we have gained from this iconic species, resulting in giant panda on the road to recovery, as we reflect on some of the most “more than 70 scientific publications. While we are delighted that the panda was downlisted poignant and personal moments that have marked this journey. from Endangered to Vulnerable last year on the IUCN Red List of Threatened Species, we know this beloved animal still needs our help—the goal is nothing less than a sustainable population on remembers his beginning as if it were yesterday. -

2014 Breeding and Management Recommendations and Summary of the Status of the Giant Panda Ex Situ Population

Report to: Chinese Association of Zoological Gardens (CAZG) Giant Panda Office, Department of Wildlife Conservation, State Forestry Administration Giant Panda Conservation Foundation (GPCF) 2014 Breeding and Management Recommendations and Summary of the Status of the Giant Panda Ex Situ Population 7 - 9 November 2013 Chengdu, China Submitted by: Kathy Traylor-Holzer, Ph.D. Jonathan D. Ballou, Ph.D. IUCN/SSC Conservation Breeding Specialist Group Chinese translation provided by: Yan Ping Sponsored by: Smithsonian Conservation Biology Institute Executive Summary This is a report on the meeting held 7 - 9 November 2013 in Chengdu, China to update the analysis of the ex situ population of giant pandas and develop breeding recommendations for the 2014 breeding season. This is the 12th annual set of genetic management recommendations developed for giant pandas. The current ex situ population of giant pandas consists of 375 animals (169 males, 205 females, 1 unsexed panda) located in 72 institutions worldwide. In 2013 there were 49 births and 13 deaths. The genetic status of the population is currently healthy, with 52 founders represented and another 14 that could be genetically represented if they were to successfully breed. There are only 3 inbred animals with inbreeding coefficients > 3% in the population. There are 50 giant pandas in the studbook that are living or have living descendents and for which the sire is uncertain. Most of these are pandas that were born in 2006 or later and are the result of natural mating and/or artificial insemination with multiple males. The result is that 10% of the gene pool of the ex situ population is derived from uncertain ancestry. -

The San Diego Zoo and Balboa Park

THE SAN DIEGO ZOO AND BALBOA PARK The San Diego Zoo occupies a special place in San Diego in terms of its local appeal and its non-local celebrity. To many it is the number one symbol of San Diego. It is the first topic someone who has heard of the City is likely to ask about. It would be pointless to claim it is the best Zoo in the United States or in the world. Nonetheless, it can be ranked as one of the world’s best zoos with or without the Wild Animal Park that acts as a counterpart to the centrally-located Zoo. The Wild Animal Park is within the sprawling territory of San Diego though it is closer to downtown Escondido than to downtown San Diego. If a zoo is to be considered as a progressive, scientific and humane institution the Wild Animal Park is ahead of the San Diego Zoo, which is handicapped by a plan that grew out of a past when standards for the care of animals were perfunctory and love of animals was at a sentimental and unscientific level.(1) In 1916, J.C. Thompson, a surgeon in the U. S. Navy seriously proposed that school children should feed the animals in the upcoming San Diego Zoo the remains of their lunches!(2) The Zoo existed in Balboa Park before the Panama-California Exposition of 1915. There were paddocks for animals and birds scattered about the park, in level land and in canyons. Visitations were not restricted as the animals were meant to be seen; however fences kept people from getting too close.