COMPLAINT PI'l;MI: £13/113 39T1d 1E1£866813T:>

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Alumni News-September-#2 023~.Pdf

Alumni News (U.S.P.S. ######) is published quarterly by the President and Board of Trustees of Santa Clara College, Donohoe Alumni House, Santa Clara University, Santa Clara, CALIFORNIA 95053-0001. Second-Class Postage Pending at Santa Clara, California. POSTMASTER: Send address changes to "Alumni News", Donohoe Alumni House, Santa Clara University, Santa Clara CALIFORNIA 95053-0001 Alumni News The Newsletter of the Santa Clara University Alumni Association um um Rock Ave. September 1992 Vol. VI No. 2 Al 4363 Martha Martha O. Guerrero-Soto SCU’s 141st Undergraduate Commencement 95127 San Jose,California Ancient Peoples of the Americas SCU and the Columbus Highlighted in Commencement Address Quincentennial By Sunny Merik the world for those who come in the F o r almost a decade, Santa human river behind us.” Clara University has periodically "Graduation means growth. It Valdez received an honorary offered special institutes devoted means making the grade. It is a doctor of fine arts degree before his to topics of unusual interest and gradual process toward what the address. Other honorary degree importance, such as social justice Aztecs called finding your own face,” Photo by Charles B arry recipients were Robert McAfee and poverty. said undergraduate commencement Brown, professor emeritus of Throughout the entire fall term speaker Luis Valdez to more than theology and ethics at the Pacific of 1992, SCU will sponsor a 1,000 undergraduates and their School of Religion, a doctor of University institute marking the friends and families on Saturday sacred theology; and Alice Gallin, quincentennary of the encounter morning, June 13. OSU, executive director of the between the European and The director, playwright, and Association of Catholic Colleges American worlds. -

Repeal of Baseball's Longstanding Antitrust Exemption: Did Congress Strike out Again?

Repeal of Baseball's Longstanding Antitrust Exemption: Did Congress Strike out Again? INTRODUCrION "Baseball is everybody's business."' We have just witnessed the conclusion of perhaps the greatest baseball season in the history of the game. Not one, but two men broke the "unbreakable" record of sixty-one home-runs set by New York Yankee great Roger Maris in 1961;2 four men hit over fifty home-runs, a number that had only been surpassed fifteen times in the past fifty-six years,3 while thirty-three players hit over thirty home runs;4 Barry Bonds became the only player to record 400 home-runs and 400 stolen bases in a career;5 and Alex Rodriguez, a twenty-three-year-old shortstop, joined Bonds and Jose Canseco as one of only three men to have recorded forty home-runs and forty stolen bases in a 6 single season. This was not only an offensive explosion either. A twenty- year-old struck out twenty batters in a game, the record for a nine inning 7 game; a perfect game was pitched;' and Roger Clemens of the Toronto Blue Jays won his unprecedented fifth Cy Young award.9 Also, the Yankees won 1. Flood v. Kuhn, 309 F. Supp. 793, 797 (S.D.N.Y. 1970). 2. Mark McGwire hit 70 home runs and Sammy Sosa hit 66. Frederick C. Klein, There Was More to the Baseball Season Than McGwire, WALL ST. J., Oct. 2, 1998, at W8. 3. McGwire, Sosa, Ken Griffey Jr., and Greg Vaughn did this for the St. -

NLDS Notes GM 4.Indd

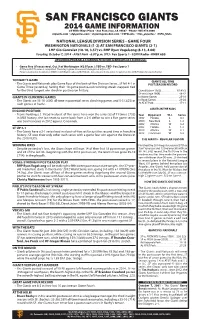

SAN FRANCISCO GIANTS 2014 GAME INFORMATION 24 Willie Mays Plaza •San Francisco, CA 94107 •Phone: 415-972-2000 sfgiants.com •sfgigantes.com •sfgiantspressbox.com •@SFGiants •@los_gigantes• @SFG_Stats NATIONAL LEAGUE DIVISION SERIES - GAME FOUR WASHINGTON NATIONALS (1-2) AT SAN FRANCISCO GIANTS (2-1) LHP Gio Gonzalez (10-10, 3.57) vs. RHP Ryan Vogelsong (8-13, 4.00) Tuesday, October 7, 2014 • AT&T Park • 6:07 p.m. (PT) • Fox Sports 1 • ESPN Radio • KNBR 680 UPCOMING PROBABLE STARTING PITCHERS & BROADCAST SCHEDULE: • Game Five (if necessary), Oct. 9 at Washington (#2:07p.m.): TBD vs. TBD- Fox Sports 1 # If the LAD/STL series is completed, Thursday's game time would change to 5:37p.m. PT Please note all games broadcast on KNBR 680 AM (English radio) and ESPN Radio. All postseason home games broadcast on 860 AM ESPN Deportes (Spanish radio). TONIGHT'S GAME GIANTS ALL-TIME • The Giants and Nationals play Game Four of this best-of- ve Division Series...SF fell 4-1 in POSTSEASON RECORD Game Three yesterday, having their 10-game postseason winning streak snapped, tied for the third-longest win streak in postseason history. Overall (since 1900) . 87-83-2 SF-era (since 1958) . .48-42 GIANTS IN CLINCHING GAMES In Home Games . .25-18 • The Giants are 15-10 (.600) all-time in potential series clinching games and 5-3 (.625) in In Road Games. .23-24 such games at home. At AT&T Park . .17-11 GIANTS IN THE NLDS IN GOOD POSITION • Teams holding a 2-1 lead in a best-of- ve series have won the series 52 of 71 times (.732) Year Opponent W-L Series in MLB history...the last team to come back from a 2-0 de cit to win a ve game series 1997 Florida L 0-3 was San Francisco in 2012 against Cincinnati. -

Seattle Mariners Opening Day Record Book

SEATTLE MARINERS OPENING DAY RECORD BOOK 1977-2012 All-Time Openers Year Date Day Opponent Att. Time Score D/N 1977 4/6 Wed. CAL 57,762 2:40 L, 0-1 N 1978 4/5 Wed. MIN 45,235 2:15 W, 3-2 N 1979 4/4 Wed. CAL 37,748 2:23 W, 5-4 N 1980 4/9 Wed. TOR 22,588 2:34 W, 8-6 N 1981 4/9 Thurs. CAL 33,317 2:14 L, 2-6 N 1982 4/6 Tue. at MIN 52,279 2:32 W, 11-7 N 1983 4/5 Tue. NYY 37,015 2:53 W, 5-4 N 1984 4/4 Wed. TOR 43,200 2:50 W, 3-2 (10) N 1985 4/9 Tue. OAK 37,161 2:56 W, 6-3 N 1986 4/8 Tue. CAL 42,121 3:22 W, 8-4 (10) N 1987 4/7 Tue. at CAL 37,097 2:42 L, 1-7 D 1988 4/4 Mon. at OAK 45,333 2:24 L, 1-4 N 1989 4/3 Mon. at OAK 46,163 2:19 L, 2-3 N 1990 4/9 Mon. at CAL 38,406 2:56 W, 7-4 N 1991 4/9 Tue. CAL 53,671 2:40 L, 2-3 N 1992 4/6 Mon. TEX 55,918 3:52 L, 10-12 N 1993 4/6 Tue. TOR 56,120 2:41 W, 8-1 N 1994 4/4 Mon. at CLE 41,459 3:29 L, 3-4 (11) D 1995 4/27 Thurs. -

An Analysis of the Nba Luxury Tax

IS IT BETTER TO GIVE OR RECEIVE? AN ANALYSIS OF THE NBA LUXURY TAX. A THESIS Presented to The Faculty of the Department of Economics and Business The Colorado College In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Bachelor of Arts By Ricky Boebel April, 2015 1 IS IT BETTER TO GIVE OR RECEIVE? AN ANALYSIS OF THE NBA LUXURY TAX. Ricky Boebel April, 2015 Mathematical Economics Abstract The results showed that teams that project themselves to have a winning record should breach the tax threshold. However, these franchises should not pay beyond one standard deviation of the average tax figure in a given year. Teams that project themselves to have a losing record should stay under the threshold. This is surprising as many franchises, particularly those in small markets, often go to drastic lengths to stay below the tax to the detriment of on and off-court performance. Over the period studied, an average of 6 teams paid the tax. The model found that regardless of market size around 15 teams per year would increase franchise net worth by having payrolls above the tax. KEYWORDS: (NBA, Tax, Salary Cap, Net Worth) JEL CODES: (A100, C120, J000) 2 ON MY HONOR, I HAVE NEITHER GIVEN NOR RECEIVED UNAUTHORIZED AID ON THIS THESIS Signature 3 TABLE OF CONTENTS Abstract ................................................................................................................ 2 Acknowledgements .............................................................................................. 5 Introduction .......................................................................................................... -

Baseball 06.Qxd

Gregg Davies, the Tigers career leader in base hits, runs scored, doubles, triples and runs batted in. BaseballBaseball HistoryHistory Tiger Baseball History Tiger Baseball Records Records Single Game Individual Records Single Game Team Records Single Season Hitting Records Most At Bats . 7, ten times At Bats . 55, vs. Northeastern (14 inn.), 1997 Most Games Played . 60, 2001 Most Hits . 5, Shane Justis, at W&M, 2005 Base Hits . 28, vs. Maine, Am. East Tour., 2001 Most At Bats . 2061, 2005 5, Mike Costello, at W & Mary, 2003 Runs Scored. 30, vs. Richmond, 2005 Most Runs Scored . 462, 2005 5, Mike Costello, at James Madison, 2003 Runs In Inning. 14, vs. Richmond (1st), 2005 Most Base Hits . 637, 2005 5, Gregg Davies, vs. Maine, 2001 Largest Deficit Overcome To Win Most Doubles . 130, 2001 5, Casey Stidham, vs. Bucknell, 2001 . 12, at Delaware (20-19), 2005 Most Triples . 22, 1981 5, Ryan Avila, vs Iona College, 1999 Doubles. 9, at Long Island University, 2002 Most Home Runs . *105, 2005 5, Nick Agoglia, at Hartford, 1997 Triples . 4, at George Washington, 1981 Most Total Bases . 1112, 2005 5, Steve Farling, vs. Delaware, 1991 Home Runs . 8, vs. Delaware, 1991 Most Bases On Balls . 260, 2005 5, Steve Farling, vs. Mt. St. Mary s, 1991 Home Runs In An Inning . 4, vs. Air Force, 2002 Most Players Hit By Pitch . 72, 2005 5, Dave Cassard, at Liberty, 1989 Runs Batted In . 29, vs. Richmond, 2005 Most Strikeouts . 404, 2005 5, John Matheis, at Drexel, 1983 Total Bases . 51, vs. Delaware, 1991 Most Stolen Bases . -

Virtual Fall Summit Agenda

NSF VIRTUAL FALL SUMMIT ‘20 September 16-17, 2020 The NSF is going virtual with the new NSF Virtual Summit Series! The Summit Series will consist of three (3) Summits that include everything attendees love about the National Sports Forum, but in a more intimate, virtual setting. Each of these unique Summits will give attendees the chance to experience two days filled with networking, education, and idea-sharing with the industry‘s best & brightest right at their fingertips. We‘re bringing the Forum Family together again, and you won‘t want to miss it! To register or for more information visit www.sports-forum.com/virtual-fall-summit/ or contact Melissa Salaya [email protected] OR 949.282.3535 WEDNESDAY | SEPTEMBER 16, 2020 ALL TIMES PACIFIC TIME ZONE Time PROGRAM (All Programming Virtual) (All Times Pacific Time) SPEAKERS 9:00am Opening Welcome Ron Seaver, President, National Sports Forum 9:00am Keynote Session: “From Where I Sit - A Candid Conversation with Nick Kelly” Nick Kelly, VP, Partnerships, Beer Culture & Community, Anheuser-Busch 10:00am Budweiser Networking Lounge & Trade Show Hall Presented By: MORNING WORKSHOPS 10:30am TICKET SALES Jeff Tucker, Vice President, Ticket & Premium Revenue, San Francisco Giants SPONSORSHIP SALES Presented By: Andy Szabo, Senior Manager, Corporate Partnerships , Oakland A’s David Martinez, Director, Global Sponsorships, SAP MARKETING Lane Joyce, Head of Experiential Marketing, Anheuser-Busch Inbev Presented By: Doug Bentz, Vice President, Marketing & Digital, San Jose Sharks Dan Hall NON-TRADITIONAL -

Dayton Dragons 2014 Media Guide

DAYTON DRAGONS 2014 MEDIA GUIDE Nick Travieso Reds #1 Draft Pick, 2012 20142014 DDAYTONAYTON DDRAGONSRAGONS MMEDIAEDIA GGUIDEUIDE Table of Contents Front Office and Ownership Info Cincinnati Reds Front Office Info 2 Front Office Staff 88 Dragons Honors 3 Field Staff and Player Development 89 Fifth Third Field 4 2013 Draft Selections 90 Mandalay Baseball 5 Reds 2013 Minor League Player/Year 91 Mandalay Baseball Teams 6 Reds 2013 Organizational Leaders 93 2014 Reds Minor League Affiliates 94 2014 Dayton Dragons Field Staff 8 Miscellaneous & Media Information Player Bios 11 Dragons Medical Staff 99 2013 Dayton Dragons Review Dragons Media Relations 100 Season Review 20 and Media Outlets Opening Day Roster 22 MWL Telephone Directory 101 Transactions 23 Dragons “On the Air” 102 Statistics 24 2014 Media Regulations 103 Season-Highs, Misc. Stats 26 2014 Pre-Game Schedule and Ground 104 Game-by-Game 28 Rules Batter/Pitcher of the Month 30 Dragons Year-by-Year, All-Stars 31 Dayton Dragons Franchise Records All-Time Regular Season 32 Dragons Season Team Records 33 Dragons Single Game Team Records 34 Dragons Individual Game Records 35 Dragons Individual Season Records 36 Dragons Career Records 38 Dragons Year-by-Year Team Statistics 40 Dragons All-Time Roster 53 All-Time Managers, Coaches 56 All-Time Opening Day Lineups 57 Baseball America Top Prospect Lists 58 Dragons MLB Debuts 59 Midwest League/Minor Leagues General Information 62 MWL Team Pages 63 2013 Midwest League Recap 78 Midwest League Mileage Chart 83 Hotel Information 84 Minor League Baseball Directory 86 “The Streak,” Attendance Leaders 87 Jay Bruce The 2014 Dayton Dragons Media Guide was produced by the Dayton Dragons Media Relations Department and its entire contents are copyrighted by Dayton Dragons Professional Baseball, LLC. -

Chapter 1, Introduction

CHAPTER 1 Introduction This Draft Environmental Impact Report (EIR) has been prepared pursuant to the California Environmental Quality Act (CEQA) and the State CEQA Guidelines to analyze potential physical environmental impacts of the proposed Oakland Waterfront Ballpark District Project (referred to in this EIR as “Project”).1 A brief overview of the Project and the environmental review process, and a description of the purpose of this Draft EIR and opportunities for public comment, are provided below, along with an explanation of how this Draft EIR is organized. 1.1 Project Overview The Oakland Athletics Investment Group, LLC (referred to in this EIR as “Oakland A’s” or “Project sponsor”) is proposing to acquire the rights to develop a site known as the Charles P. Howard Terminal (Howard Terminal) on the Oakland waterfront from the Port of Oakland (Port); acquire the rights to adjacent properties from private owners; and construct a new Major League Baseball (MLB) ballpark, as well as residential, entertainment, office, hotel, and retail (mixed- use) development, creating a new Oakland Waterfront Ballpark District. The proposed Project would be constructed in phases as described below and consistent with the site plan and street grid provided in Chapter 3, Project Description, of this Draft EIR. The Project site proposed for development of the new ballpark district includes the Howard Terminal and certain adjacent properties totaling approximately 55 acres. The Project site is located on the Oakland waterfront, north of and across the Oakland-Alameda Estuary from the City of Alameda. A location map and aerial photographs of the Project site and the surrounding vicinity are provided in Chapter 3. -

Supreme Court of the United States

No. 14-_____ ================================================================ In The Supreme Court of the United States --------------------------------- --------------------------------- CITY OF SAN JOSÉ, CITY OF SAN JOSÉ AS SUCCESSOR AGENCY TO THE REDEVELOPMENT AGENCY OF THE CITY OF SAN JOSÉ, AND THE SAN JOSÉ DIRIDON DEVELOPMENT AUTHORITY, Petitioners, v. OFFICE OF THE COMMISSIONER OF BASEBALL, an unincorporated association doing business as Major League Baseball, and ALLAN HUBER “BUD” SELIG, Respondents. --------------------------------- --------------------------------- On Petition For A Writ Of Certiorari To The United States Court Of Appeals For The Ninth Circuit --------------------------------- --------------------------------- PETITION FOR A WRIT OF CERTIORARI --------------------------------- --------------------------------- STUART BANNER JOSEPH W. C OTCHETT UCLA SCHOOL OF LAW Counsel of Record 405 Hilgard Ave. PHILIP L. GREGORY Los Angeles, CA 90095 ANNE MARIE MURPHY CAMILO ARTIGA-PURCELL RICHARD DOYLE COTCHETT, PITRE & MCCARTHY NORA FRIMANN 840 Malcolm Rd. OFFICE OF THE CITY ATTY. Burlingame, CA 94010 200 E. Santa Clara St. (650) 697-6000 San José, CA 95113 [email protected] ================================================================ COCKLE LEGAL BRIEFS (800) 225-6964 WWW.COCKLELEGALBRIEFS.COM i QUESTION PRESENTED Whether professional baseball is exempt from antitrust law in matters relating to franchise relocation. ii LIST OF PARTIES All parties appear in the caption of the case on the cover page. iii TABLE -

An Analysis of the American Outdoor Sport Facility: Developing an Ideal Type on the Evolution of Professional Baseball and Football Structures

AN ANALYSIS OF THE AMERICAN OUTDOOR SPORT FACILITY: DEVELOPING AN IDEAL TYPE ON THE EVOLUTION OF PROFESSIONAL BASEBALL AND FOOTBALL STRUCTURES DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Chad S. Seifried, B.S., M.Ed. * * * * * The Ohio State University 2005 Dissertation Committee: Approved by Professor Donna Pastore, Advisor Professor Melvin Adelman _________________________________ Professor Janet Fink Advisor College of Education Copyright by Chad Seifried 2005 ABSTRACT The purpose of this study is to analyze the physical layout of the American baseball and football professional sport facility from 1850 to present and design an ideal-type appropriate for its evolution. Specifically, this study attempts to establish a logical expansion and adaptation of Bale’s Four-Stage Ideal-type on the Evolution of the Modern English Soccer Stadium appropriate for the history of professional baseball and football and that predicts future changes in American sport facilities. In essence, it is the author’s intention to provide a more coherent and comprehensive account of the evolving professional baseball and football sport facility and where it appears to be headed. This investigation concludes eight stages exist concerning the evolution of the professional baseball and football sport facility. Stages one through four primarily appeared before the beginning of the 20th century and existed as temporary structures which were small and cheaply built. Stages five and six materialize as the first permanent professional baseball and football facilities. Stage seven surfaces as a multi-purpose facility which attempted to accommodate both professional football and baseball equally. -

Children Bond with SJSU Parents Employees Fired

SERVING SAN JOSE STATE UNIVERSITY SINCE 1934 SPARTANSPARTAN DAILYDAILY WWW.THESPARTANDAILY.COM VOLUME 122, NUMBER 53 FRIDAY, APRIL 23, 2004 Children bond with SJSU parents Employees fi red for taking photos of soldiers’ caskets Associated Press WASHINGTON — The Pentagon lost its tight control over the images of coffi ns returning from Iraq as about 350 such images were released under the Freedom of Information Act and a Seattle newspaper published a similar photo taken by a military contractor. After Dover Air Force Base, the main port for returning remains, released hundreds of government photos of the ceremonies, the Defense Department ordered Thursday that no more photographs be released. In addition, two employees for defense contractor Maytag Aircraft were fi red after the Pentagon complained about a photo of fl ag-draped caskets taken by one of them appeared in the Seattle Times. In March 2003, on the eve of war in Iraq, the Pentagon ordered an end to all media coverage of ceremonies for the returning remains of soldiers killed overseas. Although Dover already had such a policy, the Pentagon action enforced a military-wide ban on images of fl ag-draped caskets that dated from late 2000 but had not been followed. With few exceptions, the ban had remained in force until recent days. But last week, about 350 photos from Dover were released under a Freedom of Information Act request by Russ Kick, a First Amendment advocate who runs a Web site called the Memory Hole (www.thememoryhole.org). Dover had recommended that Kick’s request be denied, but offi cials at Air Mobility Command headquarters at Scott Air Force Base in Illinois authorized the release on appeal.