Hysical Ducation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Schedule B: Expenditures Sch-B

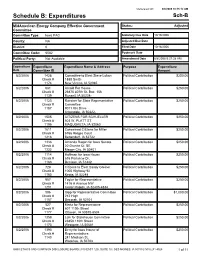

Generated On: 8/8/2008 10:15:12 AM Schedule B: Expenditures Sch-B MidAmerican Energy Company Effective Government Status: Adjusted Committee Committee Type: Iowa PAC Statutory Due Date 10/19/2006 County: NA Adjusted Due Date District: 0 Filed Date 10/18/2006 Committee Code: 6082 Postmark Date Political Party: Not Available Amendment Date 8/8/2008 9:37:38 AM Expenditure Expenditure Expenditure Name & Address Purpose Expenditure Date Committee ID Amount 8/2/2006 1428 Committee to Elect Steve Lukan Political Contribution $250.00 Check # 1888 Smith 1174 New Vienna, IA 52065 8/2/2006 681 Arnold For House Political Contribution $250.00 Check # 26875 407th St. Box 156 1139 Russell, IA 50238- 8/2/2006 1123 Raecker for State Representative Political Contribution $250.00 Check # Committee 1187 9011 Iltis Drive Urbandale, IA 50322- 8/2/2006 1505 CITIZENS FOR SCHUELLER Political Contribution $250.00 Check # 503 W. PLATT ST. 1195 MAQUOKETA, IA 52060 8/2/2006 1611 Concerned Citizens for Miller Political Contribution $250.00 Check # 6766 Ridges Court 1216 Bettendorf, IA 52722 8/2/2006 1336 Amanda Ragan for Iowa Senate Political Contribution $250.00 Check # 20 Granite Ct. SE 1232 Mason City, IA 50401 8/2/2006 1114 Hoffman for Iowa House Political Contribution $250.00 Check # 616 Parkview Dr. 1163 Denison, IA 51442 8/2/2006 728 Citizens to Elect Sandy Greiner Political Contribution $250.00 Check # 1005 Highway 92 1160 Keota, IA 52248 8/2/2006 957 Taylor for Representative Political Contribution $250.00 Check # 1416 A Avenue NW 1201 Cedar Rapids, IA 52405-4834 8/2/2006 586 Gipp for Representative Committee Political Contribution $1,000.00 Check # 212 High 1157 Decorah, IA 52101 8/2/2006 527 Mertz for Representative Political Contribution $250.00 Check # 607 110th Street 1177 Ottosen, IA 50570-8504 8/2/2006 1359 Lalk for Statehouse Committee Political Contribution $250.00 Check # 23858 110th Street 1173 Westgate, IA 50681 8/2/2006 1393 Berry for Iowa House of Political Contribution $250.00 Check # Representatives 1143 241 Madison St. -

Iowa League of Cities Annual Conference & Exhibit

Iowa League of Cities Annual Conference & Exhibit Under the Dome Dustin Miller, Governmental Affairs Manager, Iowa League of Cities Handouts and presentations are available online at www.iowaleague.org Outline: • League Legislative Advocacy • Who • What • League Challenges • Breadth • Membership • No PAC • League Strengths • Grassroots • Membership Action • Collaborate • Build Relationships with Legislators • Advocate for Your City • Inform • Issue Preview for Next Session • League Proposed Priorities and Background League Legislative Advocacy What We Do: • The League has represented city interests before the General Assembly since its inception over 110 years ago. • Through legislative advocacy, one of the League’s core values, the League continues to ensure Iowa’s cities can thrive and grow, and to make certain their citizens enjoy a superior quality of life. League Legislative Team: Who • League Staff • Dustin Miller, Governmental Affairs Manager • Erin Mullenix, Research & Fiscal Analyst • Alan Kemp, Executive Director • Terry Timmins, General Counsel • Bruce Bergman, General Counsel • Contract Lobbyist • Jessica Harder, Governmental Affairs Counsel League Legislative Team : What What we do Lobbyists: Other League Staff: • Work with League Policy • Executive Director Committee • Our spokesperson for • Review all bills and issue spot important issues • Discuss bills with our members • Adds weight to our and other lobbyists arguments on specific • Register on bills occasions • Work for or against legislation • Research & Fiscal affecting -

Verified Statement Registration VSR (Out-Of-State Committee)

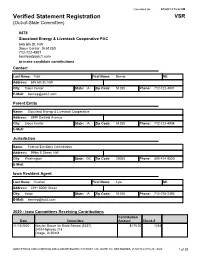

Generated On: 9/1/2021 3:15:02 PM Verified Statement Registration VSR (Out-of-State Committee) 8478 Siouxland Energy & Livestock Cooperative PAC 645 6th St, NW Sioux Center, IA 51250 712-722-4901 [email protected] to make candidate contributions Contact Last Name: Punt First Name: Bernie MI: Address: 645 6th St, NW City: Sioux Center State: IA Zip Code: 51250 Phone: 712-722-4901 E-Mail: [email protected] Parent Entity Name: Siouxland Energy & Livestock Cooperative Address: 3890 Garfield Avenue City: Sioux Center State: IA Zip Code: 51250 Phone: 712-722-4904 E-Mail: Jurisdiction Name: Federal Elections Commission Address: 999m E Street, NW City: Washington State: DC Zip Code: 20006 Phone: 800-424-9530 E-Mail: Iowa Resident Agent Last Name: Hulshof First Name: Lyle MI: Address: 2291 500th Street City: Ireton State: IA Zip Code: 51250 Phone: 712-278-2393 E-Mail: [email protected] 2020 - Iowa Committees Receiving Contributions Contribution Date Committee Amount Check # 11/13/2020 Waylon Brown for State Senate (2237) $175.00 1254 2415 Highway 218 Osage, IA 50461 IOWA ETHICS AND CAMPAIGN DISCLOSURE BOARD | 510 EAST 12th, SUITE 1A | DES MOINES, IA 50319 | (515) 281-4028 1 of 29 Generated On: 9/1/2021 3:15:02 PM 2020 - Iowa Committees Receiving Contributions Contribution Date Committee Amount Check # 10/26/2020 Timi Brown-Powers for Iowa (2163) $100.00 1033 Filed Date: 1920 W 7th St 1/6/2021 Waterloo, IA 50702 10/21/2020 Ras Smith for Governor (5196) $100.00 1029 Filed Date: 324 Madison St 1/6/2021 Waterloo, IA 50703 10/20/2020 Citizens for Sharon Steckman (1747) $150.00 1027 Filed Date: 1685 10th St SW 1/6/2021 Mason City, IA 50401-4770 10/16/2020 Citizens to Elect Bill Dotzler (1040) $100.00 1003 2837 Cedar Terrace Dr. -

SEN. BILL ANDERSON (R – Senate District 3) SEN

8 9 MEET THE SENATORS MEET THE SENATORS SEN. BILL ANDERSON (R – Senate District 3) SEN. NANCY BOETTGER (R – Senate District 9) JOB: Small business owner (tax/accounting firm) JOB: Farmer, Bed & Breakfast owner BACKGROUND: Small business owner (tax/accounting BACKGROUND: Former educator; BS Sociology ISU; BA firm); Policy advisor to Congressman Steve King AA Education Buena Vista University; Chicago native; member Northeast Community College; Army National Guard (8 of the US Center for Citizen Diplomacy. years); born and raised in Sioux City area SEN. DARYL BEALL (D – Senate District 5) SEN. JOE BOLKCOM (D – Senate District 43) JOB: Former teacher and journalist JOB: Former teacher and journalist BACKGROUND: Served two terms Fort Dodge School Board BACKGROUND: Served two terms Fort Dodge School Board AA Iowa Central Community College; BA from Buena Vista AA Iowa Central Community College; BA from Buena Vista University; MPA from Drake University. University; MPA from Drake University. OTHER: Early Access Board, Kiwanis, Izaak Walton League OTHER: Early Access Board, Kiwanis, Izaak Walton League SEN. JERRY BEHN (R – Senate District 24) SEN. TOD BOWMAN (D – Senate District 29) JOB: Farmer JOB: Teacher (political science, sociology, current events & BACKGROUND: Former Boone County Supervisor, United psychology) & coach (wrestling and football) Community High School BACKGROUND: BA Social Sciences & Education Luther OTHER: Member of Farm Bureau, Soybean Association, College; MA Western Illinois University; Model UN Director; National Rifle Association, business groups Service Learning Coordinator; Little League coach SEN. RICK BERTRAND (R – Senate District 7) NEW! SEN. CHRIS BRASE (D – Senate District 46) JOB: Owner, TARINI Wines and JAR imports; commercial JOB: Professional fire fighter and paramedic developer; formerly in health care sales BACKGROUND: North Scott High School; Scott BACKGROUND: United Community High School; BS Community College (EMT Certificate); University of Iowa University of Northern Iowa; Sioux City Community School (Paramedic Certificate). -

Verified Statement Registration VSR (Out-Of-State Committee)

Generated On: 11/29/2018 2:15:07 PM Verified Statement Registration VSR (Out-of-State Committee) 8052 Dupont Good Government Fund Experimental Station 328/407200 Powder Mill Rd Wilmington, DE 19803 302-695-4529 [email protected] to solicit funds from executive employees for distribution to political parties, committees, or candidates for election to federal or state offices (except Delaware). Contact Last Name: Marajh First Name: Curtis MI: V Address: Experimental Station 328/407 200 Powder Mill Rd City: Wilmington State: DE Zip Code: 19803 Phone: 302-695-4529 E-Mail: [email protected] Parent Entity Name: E. I. du Pont de Nemours & Company Address: 601 Pennsylvania Ave NW Suite 325, The North Building City: Washington State: DC Zip Code: 20004 Phone: 202-830-2104 E-Mail: [email protected] Jurisdiction Name: Federal Election Commission Address: 999 E Street, NW City: Washington State: DC Zip Code: 20463 Phone: 202-694-1100 E-Mail: Iowa Resident Agent Last Name: Haus First Name: Robert MI: J Address: 7000 NW 62nd Avenue City: Johnston State: IA Zip Code: 50131 Phone: 515-535-6290 E-Mail: 2018 - Iowa Committees Receiving Contributions Contribution Date Committee Amount Check # 11/29/2018 Amanda Ragan for Iowa Senate (1336) $500.00 7591 Filed Date: 361 S. Penn. 1D 11/29/2018 Mason City, IA 50401 IOWA ETHICS AND CAMPAIGN DISCLOSURE BOARD | 510 EAST 12th, SUITE 1A | DES MOINES, IA 50319 | (515) 281-4028 1 of 43 Generated On: 11/29/2018 2:15:07 PM 2018 - Iowa Committees Receiving Contributions Contribution Date Committee Amount Check # 11/29/2018 Karin Derry for Iowa (2368) $500.00 7590 Filed Date: 6689 River Bend Drive 11/29/2018 Johnston, IA 50131 10/23/2018 Mike Naig for Iowa Agriculture (5191) $1,500.00 7576 Filed Date: P.O. -

The Koch Agenda in Iowa: Americans for Prosperity

1 Contents Koch Industries in Iowa ................................................................................................................................... 4 Georgia-Pacific ............................................................................................................................................................ 4 Flint Hills Resources ................................................................................................................................................... 9 Koch Pipeline Company ............................................................................................................................................ 13 Koch Fertilizer/Koch Nitrogen ................................................................................................................................. 15 Koch Lobbying In Iowa .................................................................................................................................. 17 Koch Industries’ PACs In Iowa ................................................................................................................................. 17 Koch Companies Public Sector Lobbying................................................................................................................. 17 Americans for Prosperity: Lobbying .......................................................................................................................... 29 The Kochs Have Deep Ties to Joni Ernst .................................................................................................... -

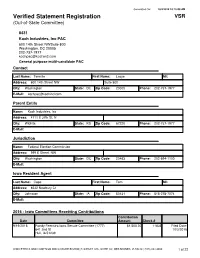

Verified Statement Registration VSR (Out-Of-State Committee)

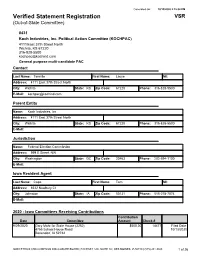

Generated On: 10/13/2020 2:15:04 PM Verified Statement Registration VSR (Out-of-State Committee) 8431 Koch Industries, Inc. Political Action Committee (KOCHPAC) 4111 East 37th Street North Wichita, KS 67220 316-828-5500 [email protected] General purpose multi-candidate PAC Contact Last Name: Tennille First Name: Lacye MI: Address: 4111 East 37th Street North City: Wichita State: KS Zip Code: 67220 Phone: 316-828-5500 E-Mail: [email protected] Parent Entity Name: Koch Industries, Inc Address: 4111 East 37th Street North City: Wichita State: KS Zip Code: 67220 Phone: 316-828-5500 E-Mail: Jurisdiction Name: Federal Election Commission Address: 999 E Street, NW City: Washington State: DC Zip Code: 20463 Phone: 202-694-1100 E-Mail: Iowa Resident Agent Last Name: Cope First Name: Tom MI: Address: 8532 Newbury Ct City: Johnston State: IA Zip Code: 50131 Phone: 515-278-7074 E-Mail: 2020 - Iowa Committees Receiving Contributions Contribution Date Committee Amount Check # 9/29/2020 Gary Mohr for State House (2252) $500.00 14477 Filed Date: 4755 School House Road 10/13/2020 Bettendorf, IA 52722 IOWA ETHICS AND CAMPAIGN DISCLOSURE BOARD | 510 EAST 12th, SUITE 1A | DES MOINES, IA 50319 | (515) 281-4028 1 of 26 Generated On: 10/13/2020 2:15:04 PM 2020 - Iowa Committees Receiving Contributions Contribution Date Committee Amount Check # 9/29/2020 Friends of Jacob Bossman (2241) $500.00 14465 Filed Date: 2650 S Cedar Street 10/13/2020 Sioux City, IA 51106 9/29/2020 Paustian for State House (1708) $1,000.00 14478 Filed Date: 389 West Parkview Drive PO Box 63 10/13/2020 Walcott, IA 52773 9/29/2020 Hein for State House (1886) $500.00 14466 Filed Date: 17358 County Road E-16 10/13/2020 Monticello, IA 52310 9/29/2020 Bergan for Iowa House (2382) $500.00 14471 Filed Date: 1204 N Bear Rd 10/13/2020 Dorchester, IA 52140 9/29/2020 Waylon Brown for State Senate (2237) $1,500.00 14482 Filed Date: 2415 Highway 218 10/13/2020 Osage, IA 50461 9/29/2020 Sinclair for Iowa (2002) $1,000.00 14489 Filed Date: 1255 King Rd. -

The Iowa County October 2010

The Iowa County 1 October 2010 2 The Iowa County October 2010 ISAC OFFICERS The Iowa County PRESIDENT Chuck Rieken - Cass County Supervisor October 2010 * Volume 39, Number 10 1ST VICE PRESIDENT Marjorie Pitts - Clay County Auditor The Iowa County: The official magazine of the 2ND VICE PRESIDENT Iowa State Association of Counties Wayne Walter - Winneshiek County Treasurer 501 SW 7th St., Ste. Q Des Moines, IA 50309 3RD VICE PRESIDENT (515) 244-7181 FAX (515) 244-6397 www.iowacounties.org Darin Raymond - Plymouth County Attorney Rachel E. Bicego, EDITOR ISAC DIRECTORS Feature 4-5 Tim McGee - Lucas County Assessor Letters from Governor Branstad and Lori Elam - Scott County Community Services Governor Culver Dan Cohen - Buchanan County Conservation Director Lori Morrissey - Story County Emergency Mgmt. Capitol Comments 6-7 Mike McClain - Jones County Engineer Linda Hinton Jon McNamee - Black Hawk County Environmental Health Wayne Chizek - Marshall County IT/GIS Legal Briefs 8 Terri Henkels - Polk County Public Health Nancy Parrott - Jasper County Recorder Nate Bonnett Mike Balmer - Jasper County Sheriff Technology Center 9, 10 Harlan Hansen - Humboldt County Supervisor Melvyn Houser - Pottawattamie County Supervisor Robin Harlow and Tammy Norman Anna O’Shea - Dubuque County Zoning Gary Anderson - Appanoose County Sheriff (Past Pres.) ISAC Meetings 11-14 Grant Veeder - Black Hawk County Auditor (NACo Rep.) 2010 ISAC Fall School of Instruction Insert Judy Miller - Pottawattamie County Treasurer (NACo Board) Lu Baron - Linn County Supervisor (NACo Board) Case Management 15 Jackie Olson Leech ISAC STAFF William R. Peterson - Executive Director ISAC Brief 16-17 Lauren Adams - Financial Administrative Assistant Rachel E. Bicego - Marketing/Comm. -

Verified Statement Registration VSR (Out-Of-State Committee)

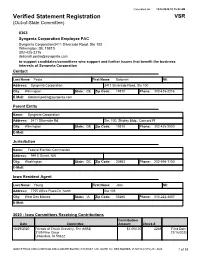

Generated On: 12/16/2020 10:15:02 AM Verified Statement Registration VSR (Out-of-State Committee) 8363 Syngenta Corporation Employee PAC Syngenta Corporation3411 Silverside Road, Ste 100 Wilmington, DE 19810 302-425-2216 [email protected] to support candidates/committees who support and further issues that benefit the business interests of Syngenta Corporation Contact Last Name: Pedia First Name: Deborah MI: Address: Syngenta Corporation 3411 Silverside Road, Ste 100 City: Wilmington State: DE Zip Code: 19810 Phone: 302-425-2216 E-Mail: [email protected] Parent Entity Name: Syngenta Corporation Address: 3411 Silverside Rd. Ste. 100, Shipley Bldg., Concord Pl City: Wilmington State: DE Zip Code: 19810 Phone: 302-425-2000 E-Mail: Jurisdiction Name: Federal Election Commission Address: 999 E Street, NW City: Washington State: DC Zip Code: 20463 Phone: 202-694-1100 E-Mail: Iowa Resident Agent Last Name: Young First Name: John MI: Address: 7755 Office Plaza Dr, North Ste 105 City: West Des Moines State: IA Zip Code: 50265 Phone: 515-222-4807 E-Mail: 2020 - Iowa Committees Receiving Contributions Contribution Date Committee Amount Check # 10/29/2020 Friends of Chuck Grassley, The (6392) $1,000.00 2268 Filed Date: 3109 Pine Circle 12/16/2020 Urbandale, IA 50322 IOWA ETHICS AND CAMPAIGN DISCLOSURE BOARD | 510 EAST 12th, SUITE 1A | DES MOINES, IA 50319 | (515) 281-4028 1 of 18 Generated On: 12/16/2020 10:15:02 AM 2020 - Iowa Committees Receiving Contributions Contribution Date Committee Amount Check # 10/29/2020 Friends of Abby Finkenauer (2111) $1,000.00 2287 Filed Date: 2421 5th Ave SE 12/16/2020 Cedar Rapids, IA 52403 9/11/2020 Randy Feenstra Iowa Senate Committee (1777) $1,000.00 2238 Filed Date: 641 2nd St 12/16/2020 Hull, IA 51239 8/13/2020 Citizens for Pat Grassley (1605) $500.00 2223 Filed Date: 30601 Deer Trail Drive 9/17/2020 New Hartford, IA 50660 8/13/2020 Citizens for Mommsen (2194) $300.00 2212 Filed Date: 2308 15th st. -

Verified Statement Registration VSR (Out-Of-State Committee)

Generated On: 10/4/2016 10:15:08 AM Verified Statement Registration VSR (Out-of-State Committee) 8431 Koch Industries, Inc PAC 600 14th Street NWSuite 800 Washington, DC 20005 202-737-1977 [email protected] General purpose multi-candidate PAC Contact Last Name: Tennille First Name: Lacye MI: Address: 600 14th Street NW Suite 800 City: Washington State: DC Zip Code: 20005 Phone: 202-737-1977 E-Mail: [email protected] Parent Entity Name: Koch Industries, Inc Address: 4111 E 37th St, N City: Wichita State: KS Zip Code: 67220 Phone: 202-737-1977 E-Mail: Jurisdiction Name: Federal Election Commission Address: 999 E Street, NW City: Washington State: DC Zip Code: 20463 Phone: 202-694-1100 E-Mail: Iowa Resident Agent Last Name: Cope First Name: Tom MI: Address: 8532 Newbury Ct City: Johnston State: IA Zip Code: 50131 Phone: 515-278-7074 E-Mail: 2016 - Iowa Committees Receiving Contributions Contribution Date Committee Amount Check # 9/19/2016 Randy Feenstra Iowa Senate Committee (1777) $1,500.00 11836 Filed Date: 641 2nd St 10/3/2016 Hull, IA 51239 IOWA ETHICS AND CAMPAIGN DISCLOSURE BOARD | 510 EAST 12th, SUITE 1A | DES MOINES, IA 50319 | (515) 281-4028 1 of 22 Generated On: 10/4/2016 10:15:08 AM 2016 - Iowa Committees Receiving Contributions Contribution Date Committee Amount Check # 9/19/2016 Chapman For Senate (1961) $1,500.00 11837 Filed Date: 25862 Fox Ridge Ln 10/3/2016 Adel, IA 50003 9/19/2016 Schneider for State Senate (2107) $1,500.00 11838 Filed Date: 7887 Cody Drive 10/3/2016 West Des Moines, IA 50266 9/19/2016 Friends for Dix (1846) $7,500.00 11839 Filed Date: 317 S Walnut 10/3/2016 Shell Rock, IA 50670 9/19/2016 Waylon Brown for State Senate (2237) $2,500.00 11840 Filed Date: 109 South Summer Street 10/3/2016 Saint Ansgar, IA 50472 9/19/2016 Friends For Breitbach (1838) $1,500.00 11841 Filed Date: 301 W. -

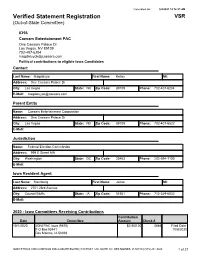

Verified Statement Registration VSR (Out-Of-State Committee)

Generated On: 5/4/2021 10:16:21 AM Verified Statement Registration VSR (Out-of-State Committee) 8356 Caesars Entertainment PAC One Caesars Palace Dr Las Vegas, NV 89109 702-407-6204 [email protected] Political contributions to eligible Iowa Candidates Contact Last Name: Magdaluyo First Name: Kelley MI: Address: One Caesars Palace Dr City: Las Vegas State: NV Zip Code: 89109 Phone: 702-407-6204 E-Mail: [email protected] Parent Entity Name: Caesars Entertainment Corporation Address: One Caesars Palace Dr City: Las Vegas State: NV Zip Code: 89109 Phone: 702-407-6522 E-Mail: Jurisdiction Name: Federal Election Commission Address: 999 E Street NW City: Washington State: DC Zip Code: 20463 Phone: 202-694-1100 E-Mail: Iowa Resident Agent Last Name: Sternberg First Name: Janae MI: Address: 2701 23rd Avenue City: Council Bluffs State: IA Zip Code: 51501 Phone: 712-329-6032 E-Mail: 2020 - Iowa Committees Receiving Contributions Contribution Date Committee Amount Check # 10/1/2020 JONI PAC Iowa (9870) $2,500.00 3846 Filed Date: P.O Box 93441 10/8/2020 Des Moines, IA 50393 IOWA ETHICS AND CAMPAIGN DISCLOSURE BOARD | 510 EAST 12th, SUITE 1A | DES MOINES, IA 50319 | (515) 281-4028 1 of 27 Generated On: 5/4/2021 10:16:21 AM 2020 - Iowa Committees Receiving Contributions Contribution Date Committee Amount Check # 9/1/2020 Chapman For Senate (1961) $250.00 3840 Filed Date: 25862 Fox Ridge Ln 10/7/2020 Adel, IA 50003 9/1/2020 Taxpayers for Mitchell (2453) $200.00 3832 Filed Date: 104 S. White st 10/7/2020 Mt Pleasant, IA 52641 9/1/2020 Bisignano for Senate Account (2115) $500.00 3823 Filed Date: 2618 East Leach Avenue 10/7/2020 Des Moines, IA 50320 9/1/2020 Friends of Jim Lykam (1397) $250.00 3839 Filed Date: 2906 W. -

2007 Issue #9

2007 Issue #9 INSIDE THIS ISSUE 8 VOTE 2008 Workshops 8President Signs Historic ADA Amendments Act 8Election Results o Democrats Expand Majorities o New Leaders Elected o New Faces in the Iowa Legislature 8Next Issue o 2009 Legislative Session Preview VOTE 2008 WORKSHOP ID Action (Iowans with Disabilities in Action) and Iowa’s Developmental Disabilities Council hit the road in September and October, talking to more than 1,200 Iowans with disabilities about their voting rights. Vote 2008 Workshops were held in 20 communities around Iowa. More than just “talk,” these workshops gave Iowans with disabilities the chance to try out new voting equipment, practice voting, meet candidates on the ballot this year, and discuss voting with their county auditors. Issue #11, 2008 November 23, 2008 ID Action and Iowa’s Developmental Disabilities Since the passage of the Americans With Council would like to thank all of the people that Disabilities Act (ADA) 18 years ago, the U.S. made these trainings a success: Supreme Court has narrowed the ADA’s coverage and excluded many individuals with disabilities • Secretary of State Michael Mauro and his from its protection. The ADAAA reinstates the staff, for providing accessible materials and original Congressional intent of the ADA by one of the new Automark voting machines, and extending protections to individuals who use participating in two of the trainings. hearing aids, prosthetic limbs or take medication to treat disabilities. • All of the county auditors and auditor staff that made themselves available to register The ADAAA classifies any condition that limits a people, teach them how to use the voting major life activity as a disability regardless of machines, and provide one-on-one help.